Fire in the Elevator: A 1989 Japanese Ruling on Arson in the Modern Apartment Building

The traditional image of arson—a fire consuming a wooden house—is deeply embedded in legal history. But what happens when the crime moves into the modern, fire-resistant world of a steel and concrete high-rise? Does a fire set in a common area, like an elevator, carry the same legal weight as one set in a private residence? Is an elevator car, a machine that moves within a shaft, even considered part of the "building" at all? And how does one define "burned" when the surrounding structure is designed specifically not to burn?

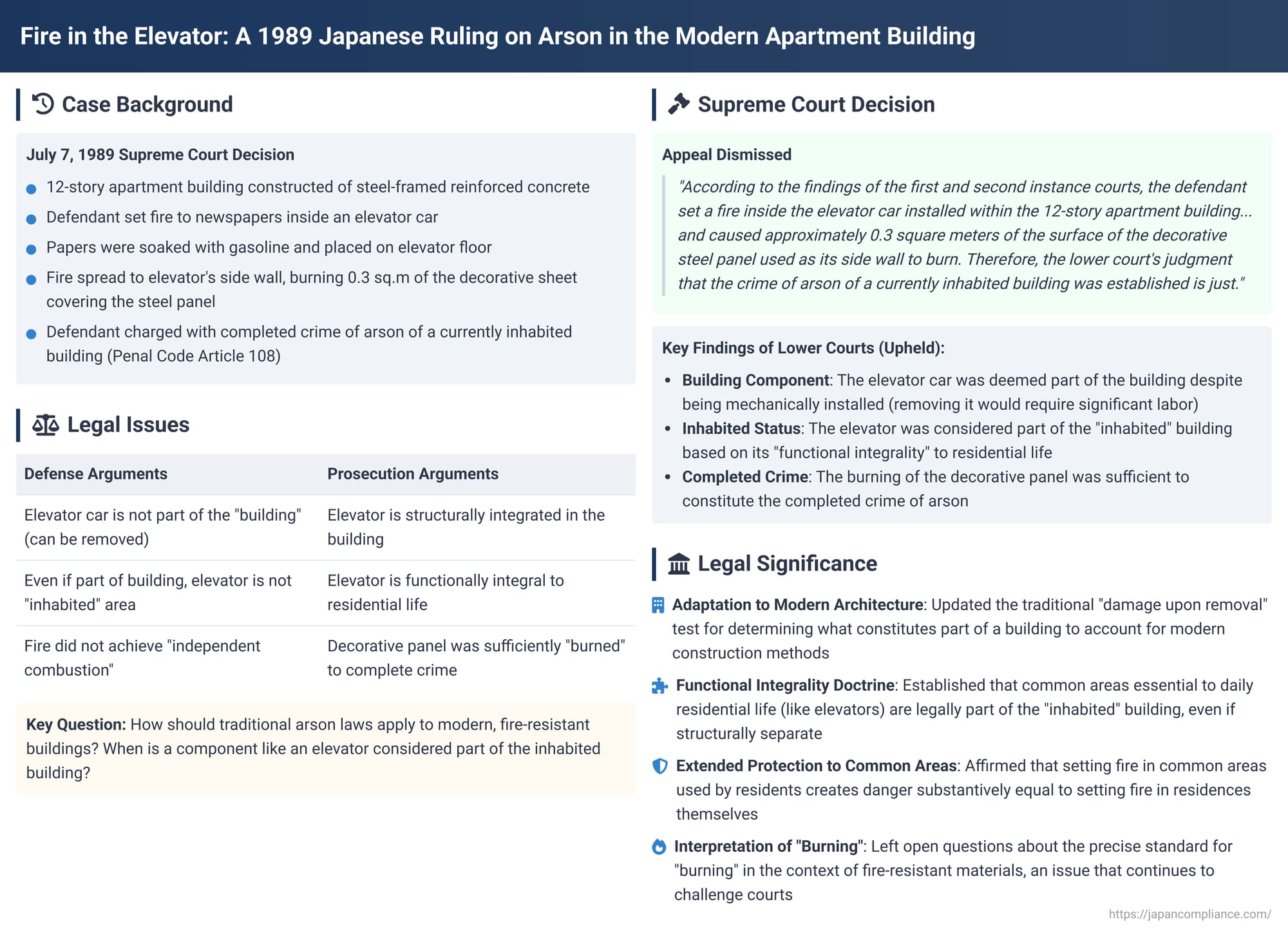

These critical questions, born from the evolution of architecture, were at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 7, 1989. In a case involving a fire set inside an elevator, the Court adapted century-old legal principles to the realities of the modern apartment building, clarifying the immense scope of Japan's most serious arson laws.

The Facts: The Fire in the 12-Story Building

The incident took place in a 12-story apartment building constructed of steel-framed reinforced concrete. The defendant, with the knowledge that it might ignite the elevator car itself, used a lighter to set fire to some newspapers. He then threw the burning papers onto other gasoline-soaked newspapers he had placed on the elevator car's floor. The fire spread to the car's side wall, burning a portion of the decorative sheet covering the steel panel.

The defendant was charged with the completed crime of arson of a currently inhabited building (Article 108 of the Penal Code), the most serious form of arson. In his defense, he mounted a three-pronged legal challenge:

- The "Building" Argument: He claimed the elevator car was not part of the building because it could be removed without being destroyed.

- The "Inhabited" Argument: Even if it were part of the building, he argued it was functionally separate from the residential units and should be treated as a "non-inhabited" structure, which carries a lesser penalty.

- The "Completed Crime" Argument: He asserted that the fire had not achieved true "independent combustion"; the decorative surface had merely melted and carbonized due to the heat from the burning gasoline. Therefore, the crime was at most an "attempt," not a completed act of arson.

The lower courts rejected these arguments, and the case ascended to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Brief but Decisive

The Supreme Court's decision was remarkably brief. It swiftly dismissed the appeal, stating:

"According to the findings of the first and second instance courts, the defendant set a fire inside the elevator car installed within the 12-story apartment building... and caused approximately 0.3 square meters of the surface of the decorative steel panel used as its side wall to burn. Therefore, the lower court's judgment that the crime of arson of a currently inhabited building was established is just."

While concise, this affirmation of the lower court's verdict carried profound legal weight, implicitly upholding the reasoning used to overcome the defense's challenges. To understand its significance, we must delve into the legal doctrines the lower court applied and the Supreme Court endorsed.

Analysis I: What Constitutes a "Building" in the Modern Age?

The first question was whether the elevator car was legally part of the building.

- The Traditional Test: A long-standing precedent from 1950 established the "damage upon removal" test. An object is considered part of a building if it cannot be removed without being "damaged" (kison). Applying this rule strictly, one could argue that an elevator car, which is ultimately a machine assembled within a shaft, is not part of the building.

- A Modern, Pragmatic Interpretation: The lower court took a more practical approach. It noted that removing the elevator car from its housing would require a team of about four workers and a full day's labor. On this basis, it concluded that the car met the standard of being in a state where it "cannot be removed without being damaged." This flexible interpretation adapts the old rule, conceived for traditional wooden construction, to the realities of modern engineering, where components are often assembled with bolts and complex machinery.

Analysis II: The "Inhabited" Building and the Rise of Functional Integrality

The more critical issue was whether a fire in a non-residential part of a residential building constitutes arson of an "inhabited" building. This distinction is vital, as the law punishes arson of an inhabited building far more severely due to the inherent danger to human life.

- The Challenge of Fire-Resistant Buildings: In modern, fire-resistant buildings, a fire in one section may pose little to no risk of spreading to another. This has led some lower courts to find that separate, fire-proofed sections (like a first-floor commercial clinic) could be treated as independent, non-inhabited structures even if they are within the same building shell as residences. Other courts have disagreed, noting that even fire-proof buildings are not immune to the spread of toxic gas or extreme heat.

- A New Standard: Physical and Functional Integrality: In another 1989 decision (the "Heian Shrine" case), the Supreme Court clarified its approach. To determine if a part is integral to the whole, courts should look at two factors:

- Physical Integrality: The structural connection, assessed with a view to the potential for fire and smoke to spread to the inhabited areas.

- Functional Integrality: The manner in which the part is used in conjunction with, and in service of, the inhabited areas.

- The Elevator Case as a Prime Example of Functional Integrality: The lower court, affirmed by the Supreme Court, found the elevator to be integral to the inhabited building primarily on functional grounds. The elevator was a common area used constantly by residents to go between floors. It was functionally essential to their daily lives and an extension of their living space. Even if the fire was unlikely to spread, setting a fire in a space so frequently used by residents created a danger that was substantively equal to setting a fire in the residence itself.

While some legal scholars criticize the concept of "functional integrality" as potentially vague and overly broad, its application here is widely seen as appropriate. It is understood not as a standalone test but as one that confirms the integrated nature of a space that is already structurally part of a single building. It is grounded in the potential danger to people who are expected to be present in that space as part of their daily habitation.

Analysis III: The Lingering Question of "Burning"

The final issue was whether the small patch of the decorative panel was truly "burned" in the sense required to complete the crime.

- The Prevailing Standard: As established in the 1950 arson case, the dominant standard is the "Independent Combustion Theory," which requires the fire to ignite the building itself and burn on its own.

- The Difficulty with Non-Flammable Materials: This standard is difficult to apply to fire-resistant materials. This has led to the proposal of a "New Loss of Utility Theory," which would consider the crime complete if the heat or toxic gas from a burning medium (like gasoline) destroys the building's utility, even without independent combustion. This theory has not been widely adopted.

- An Unanswered Question: The Supreme Court's brief decision simply states the panel was "burned." It offers no detail on the nature or duration of the combustion. This leaves open the critique that the finding might be insufficient, as the modern understanding of the "Independent Combustion Theory" requires not just a momentary spark but a fire with at least some "potential for continued burning."

Conclusion

The 1989 elevator fire case is a vital decision that skillfully adapted Japan's arson laws to the architectural realities of the 20th century. It affirmed that in modern, multi-unit dwellings, the concept of a "home" extends beyond the four walls of a private apartment. By focusing on functional integrality, the Supreme Court confirmed that common areas essential to daily life, like elevators, are considered part of the inhabited building. Setting a fire in such a space is not treated as a remote act of property damage but as a direct and grave threat to the lives of the residents. The ruling serves as a powerful reminder that the law will look beyond mere structure to the functional reality of how people live, ensuring that the most serious arson laws protect them not only in their private rooms but throughout their entire integrated dwelling.