Finance Leases in Japanese Corporate Reorganization: Are Unpaid Lease Fees Priority Claims? A 1995 Supreme Court Ruling

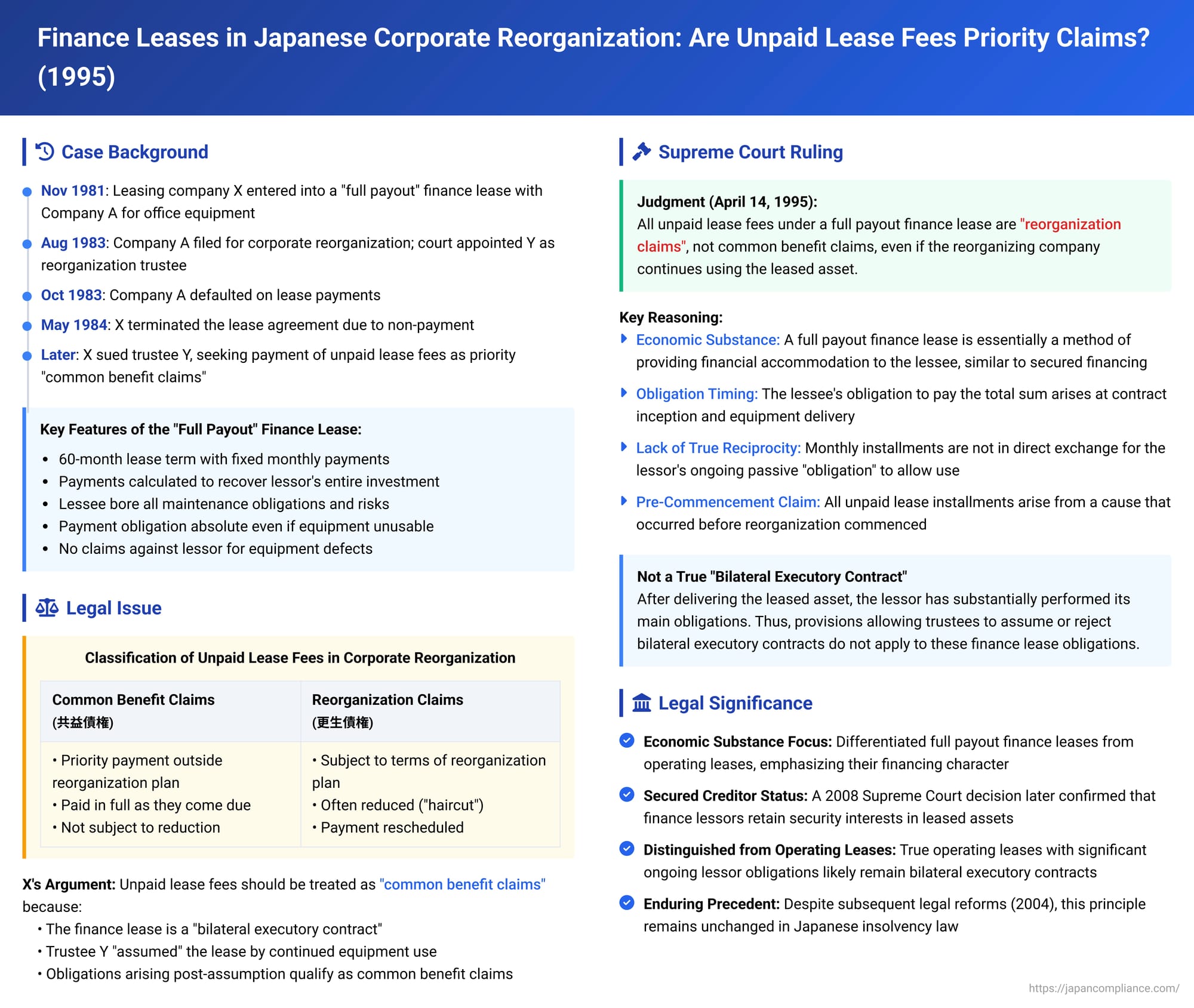

Finance leases, particularly those structured as "full payout" leases where the lessor recovers the entire cost of the asset plus profit over the lease term, are a common method for businesses to acquire equipment. From an economic perspective, these often resemble secured financing more than traditional operating leases. This distinction becomes critical when the lessee (the user of the equipment) enters corporate reorganization proceedings (会社更生手続 - kaisha kōsei tetsuzuki) in Japan. A key question then arises: how are the lessee's obligations to make future lease payments treated? Are they considered "common benefit claims" (共益債権 - kyōeki saiken), which are akin to administrative expenses and must be paid in full by the reorganizing company if it continues to use the asset? Or are they merely "reorganization claims" (更生債権 - kōsei saiken), which arose before the proceedings and are thus subject to reduction and restructuring under the reorganization plan? The Supreme Court of Japan provided a definitive answer to this pivotal question in a judgment on April 14, 1995.

Factual Background: Finance Lease, Default, and Corporate Reorganization

The case involved X, a leasing company (the lessor), and A Co. (the lessee/user). On November 18, 1981, X and A Co. entered into what was characterized as a "finance lease agreement" (本件リース契約 - honken rīsu keiyaku) for office equipment. Under the arrangement, X purchased the specified equipment from a third-party supplier (C Co.) and then leased it to A Co. X delivered the equipment to A Co. on December 1, 1981.

The lease agreement contained several typical clauses for a full payout finance lease:

- The lease term was set at 60 months.

- Lease payments were to be made monthly at a fixed rate.

- The total lease payments were calculated so that X (the lessor) would recover its entire investment in the equipment (including acquisition cost, financing charges, and profit) over the 60-month lease term, with the assumption that the equipment would have no significant residual value at the end of the term. This is known as a "full payout" (フルペイアウト方式 - furu peiauto hōshiki) lease.

- A Co. (the lessee) was responsible for all aspects of the equipment's maintenance, inspection, repair, and bore all risks associated with its loss or damage.

- A Co.'s obligation to pay the lease fees was absolute and unconditional during the lease term, even if the equipment became unusable for any reason.

- After accepting delivery of the equipment, A Co. had no right to make any claims against X (the lessor) regarding any defects in the equipment.

- If the equipment was irreparably damaged or lost due to unforeseen events like natural disasters, the lease agreement would terminate, but A Co. would still be obligated to pay a stipulated amount of damages to X.

On August 30, 1983, A Co. filed a petition for the commencement of corporate reorganization proceedings. On the same day, the court issued a preservation order, appointing a preservation administrator and prohibiting A Co. from making payments on its existing debts. On December 23, 1983, the court formally approved the commencement of corporate reorganization proceedings for A Co., and Y was appointed as its reorganization trustee (管財人 - kanzainin).

A Co. had defaulted on its lease payments to X from October 1983 onwards. Consequently, on February 8, 1984, X sent a demand to trustee Y for payment of the overdue lease fees. On May 15, 1984, X formally declared the lease agreement terminated due to A Co.'s continued non-payment.

X then initiated a lawsuit against Y (A Co.'s reorganization trustee). X sought (a) the return of the leased office equipment, and (b) payment of all unpaid lease fees, plus stipulated damages for breach of contract. X's primary argument concerning the payment claim was that the finance lease agreement constituted an ongoing bilateral contract where both parties still had unperformed obligations at the time reorganization commenced (X's obligation to allow A Co. to continue using the equipment, and A Co.'s obligation to make monthly lease payments). X contended that since trustee Y had effectively chosen to continue the contract by allowing A Co. to keep using the leased equipment after the reorganization proceedings began, any unpaid lease fees (including those that became due after commencement) should be treated as priority "common benefit claims" under Article 103, paragraph 1, and Article 208, item 7, of the (then) old Corporate Reorganization Act. (These provisions are analogous to Article 61, paragraphs 1 and 4, respectively, of the current Corporate Reorganization Act, which deal with the trustee's power to assume or reject executory contracts and the treatment of claims arising from assumed contracts as common benefit claims). As common benefit claims, X argued, these amounts were payable in full, outside the constraints of any reorganization plan.

The Tokyo District Court (first instance) dismissed X's claim for the return of the equipment (on grounds not detailed in the Supreme Court summary) and also dismissed the monetary claim as having been improperly filed as a direct lawsuit instead of through the reorganization claim process. The Tokyo High Court (second instance) upheld the dismissal of X's main claims, though it did grant a subordinate claim by X for the return of the equipment upon the eventual expiry of the original lease term. X alone appealed the dismissal of its primary monetary claim (for treatment as common benefit claims) to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Issue: Are Future Lease Payments Under a Full Payout Finance Lease Common Benefit Claims or Reorganization Claims?

The central legal question for the Supreme Court was the proper classification of the unpaid lease installments under a full payout finance lease when the lessee enters corporate reorganization. The distinction is critical:

- Common Benefit Claims (共益債権 - kyōeki saiken): These are claims that arise during or for the benefit of the reorganization proceeding itself (akin to administrative expenses). They are paid with high priority, typically in full and as they become due, directly from the debtor's assets, without being subject to the terms of the reorganization plan.

- Reorganization Claims (更生債権 - kōsei saiken): These are, generally, all monetary claims against the debtor that arose from causes occurring before the commencement of the reorganization proceedings. These claims are subject to the terms of an approved reorganization plan, which often involves significant reductions in the amount payable ("haircuts") and/or rescheduling of payments over an extended period.

X's argument hinged on the idea that the finance lease was an ongoing "bilateral executory contract where both parties still have unperformed obligations that are mutually dependent" (双方未履行双務契約 - sōhō mirikō sōmu keiyaku). If the trustee "assumes" such a contract by continuing to receive its benefits (like using the leased asset), then claims arising from the debtor's post-assumption obligations (like ongoing lease payments) become common benefit claims. The core of the dispute was whether a full payout finance lease, after the lessor has delivered the asset, truly fits this definition of an ongoing, reciprocally executory contract.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Future Lease Payments are Reorganization Claims

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of April 14, 1995, dismissed X's appeal. It held that in a "full payout" finance lease, where the lease payments are structured to enable the lessor to recover its entire investment over the lease term, all unpaid lease installments (including those that notionally fall due after the commencement of the lessee's corporate reorganization proceedings) are to be considered reorganization claims, not common benefit claims. Therefore, the lessor (X) could not demand their payment as priority common benefit claims outside the framework of A Co.'s reorganization plan.

The Court's reasoning was based on the economic substance of the transaction:

- Economic Substance of a Full Payout Finance Lease: The Court emphasized that this type of finance lease, where lease payments are calculated for the lessor to recover the entire acquisition cost of the leased asset plus other associated costs (like financing and profit), with an assumption of no significant residual value for the lessor at the end of the lease term, is, in its economic substance, a method of providing financial accommodation to the user (the lessee). It functions more like a secured loan or an installment sale financing than a true rental or operating lease.

- Lessee's Obligation to Pay Total Lease Fees Arises at Contract Inception: The Court found that in such a full payout finance lease, the lessee's fundamental obligation to pay the total sum of all stipulated lease payments over the entire lease term arises at the time the contract is concluded and the leased asset is delivered to the lessee. The common arrangement for these payments to be made in monthly installments is merely a way of granting the lessee the "benefit of time" (期限の利益 - kigen no rieki) for satisfying this pre-existing aggregate obligation.

- Lack of True Reciprocity for Ongoing Monthly Payments: After the lessor has fulfilled its primary obligation by acquiring and delivering the leased asset to the lessee, the lessor's ongoing "obligation" is largely passive—simply to allow the lessee to continue using the asset. The Supreme Court determined that the individual monthly lease payments made by the lessee are not in a direct, ongoing, reciprocal (give-and-take, 対価関係 - taika kankei) relationship with this passive obligation of the lessor to permit use. This is different from, for example, a true operating lease where the monthly rent is directly exchanged for the ongoing provision of the premises or services for that month. In a full payout finance lease, the monthly payments are essentially installments towards the total financing cost.

- All Unpaid Lease Fees are Pre-Commencement Claims: Consequently, at the moment the lessee's corporate reorganization proceedings commence, all unpaid lease installments—including those whose contractual payment dates fall after the commencement of the proceedings—are considered to be "claims arising from a cause that occurred before the commencement of reorganization proceedings" as defined in Article 102 of the old Corporate Reorganization Act (similar to Article 2, paragraph 8, of the current Act, which defines reorganization claims). They are therefore properly classified as reorganization claims.

- Trustee's Power to Assume or Reject Bilateral Executory Contracts (Old Art. 103(1)) Does Not Apply: The statutory provision that allows a reorganization trustee to choose either to assume (and continue performing) or to reject ongoing bilateral contracts where both parties still have significant unperformed obligations that are mutually dependent (Article 103, paragraph 1, of the old Act, similar to Article 61, paragraph 1, of the current Act) does not apply to these full payout finance lease payment obligations. This is because the lessor (X), having already delivered the leased asset, is generally considered to have substantially performed its main obligations under the contract. There is no significant ongoing, unperformed, reciprocal obligation on the lessor's part that is directly linked to the lessee's future obligation to make individual lease payments.

- Conclusion on Claim Status: As a result, the Supreme Court concluded that the unpaid lease fees could not become "common benefit claims" under Article 208, item 7, of the old Corporate Reorganization Act (similar to Article 61, paragraph 4, of the current Act, which grants common benefit status to claims arising from contracts that have been properly assumed by the trustee). The Court found no other basis for treating these unpaid lease fees as priority common benefit claims.

Implications of the Decision

This 1995 Supreme Court judgment had, and continues to have, profound implications for the treatment of finance leases in Japanese corporate insolvency proceedings:

- Clarification of Finance Lease Treatment in Reorganization: It was a landmark decision that clearly differentiated "full payout" finance leases from true operating leases for the purpose of claim classification in corporate reorganization. It effectively aligned the treatment of such finance leases with that of secured financing arrangements, focusing on their economic substance.

- Position of Finance Lessors in Reorganization: The ruling means that finance lessors, under full payout leases, cannot generally expect to receive full payment of all post-commencement lease installments as priority common benefit claims, even if the reorganizing lessee continues to use the leased asset. Their entire remaining lease receivable (including future installments, which are typically discounted to their present value for claim purposes) becomes a general reorganization claim, subject to the terms and potential compromises of the reorganization plan.

- Lessor's Underlying Security Interest Remains: It is crucial to note, as the PDF commentary emphasizes, that while this judgment classifies the monetary claim for future lease payments as a reorganization claim, it does not strip the finance lessor of their underlying security interest in the leased asset itself. A subsequent, and equally important, Supreme Court decision on December 16, 2008 (Heisei 20 (Ju) No. 1216, often referred to as "BK77" in legal commentaries), explicitly recognized that the leased asset in a finance lease serves a critical security function for the lessor. This means the lessor can repossess the asset upon the lessee's default (subject to certain insolvency law restrictions) and realize its value to cover unpaid lease fees and any stipulated damages. Thus, a finance lessor is typically treated as a reorganization secured creditor (更生担保権者 - kōsei tanpo kensha). As such, their secured claim (up to the value of the leased collateral) receives more favorable treatment under the reorganization plan than general unsecured reorganization claims, and their right to the asset (or its value) is protected, though its exercise may be shaped by the plan.

- Distinction from True Operating Leases: The logic of the 1995 ruling strongly suggests that true operating leases, where the lessor retains significant ongoing obligations (e.g., maintenance, services, insurance) and bears the residual value risk of the asset, would likely continue to be treated as ongoing bilateral executory contracts. In such cases, if the reorganization trustee chooses to assume the lease and continue using the asset post-commencement, the ensuing lease payments would likely qualify as common benefit claims.

- Legislative Status Quo: The PDF commentary points out that despite extensive discussions during subsequent major revisions of Japan's bankruptcy law (in 2004) and the law of obligations within the Civil Code, the Diet (Japan's parliament) did not enact specific statutory provisions to alter the fundamental judicial treatment of finance leases as established by this 1995 Supreme Court decision and related case law. This makes the 1995 judgment a continuing and highly influential leading authority on the subject.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's April 14, 1995, decision firmly established that in the context of a "full payout" finance lease, all unpaid lease installments, including those notionally falling due after the lessee enters corporate reorganization proceedings, are to be treated as pre-commencement reorganization claims. They do not automatically become priority common benefit claims simply because the reorganizing debtor continues to use the leased asset. This classification stems from the Court's view of such leases as being, in their economic substance, a form of financial accommodation where the lessor's primary performance (delivery of the asset) is completed at the outset, and the lessee's obligation to pay the total sum of lease fees arises at that point. While the lessor's monetary claim for future payments is subject to the reorganization plan, their underlying security interest in the leased asset itself is generally recognized, affording them the status and protections of a reorganization secured creditor. This judgment remains a cornerstone for understanding the treatment of finance lease obligations within Japanese corporate restructuring law.