Finality of Assignment Orders: Japanese Supreme Court Clarifies Priority over Later Mortgagee Subrogation Claims

Date of Supreme Court Decision: March 12, 2002

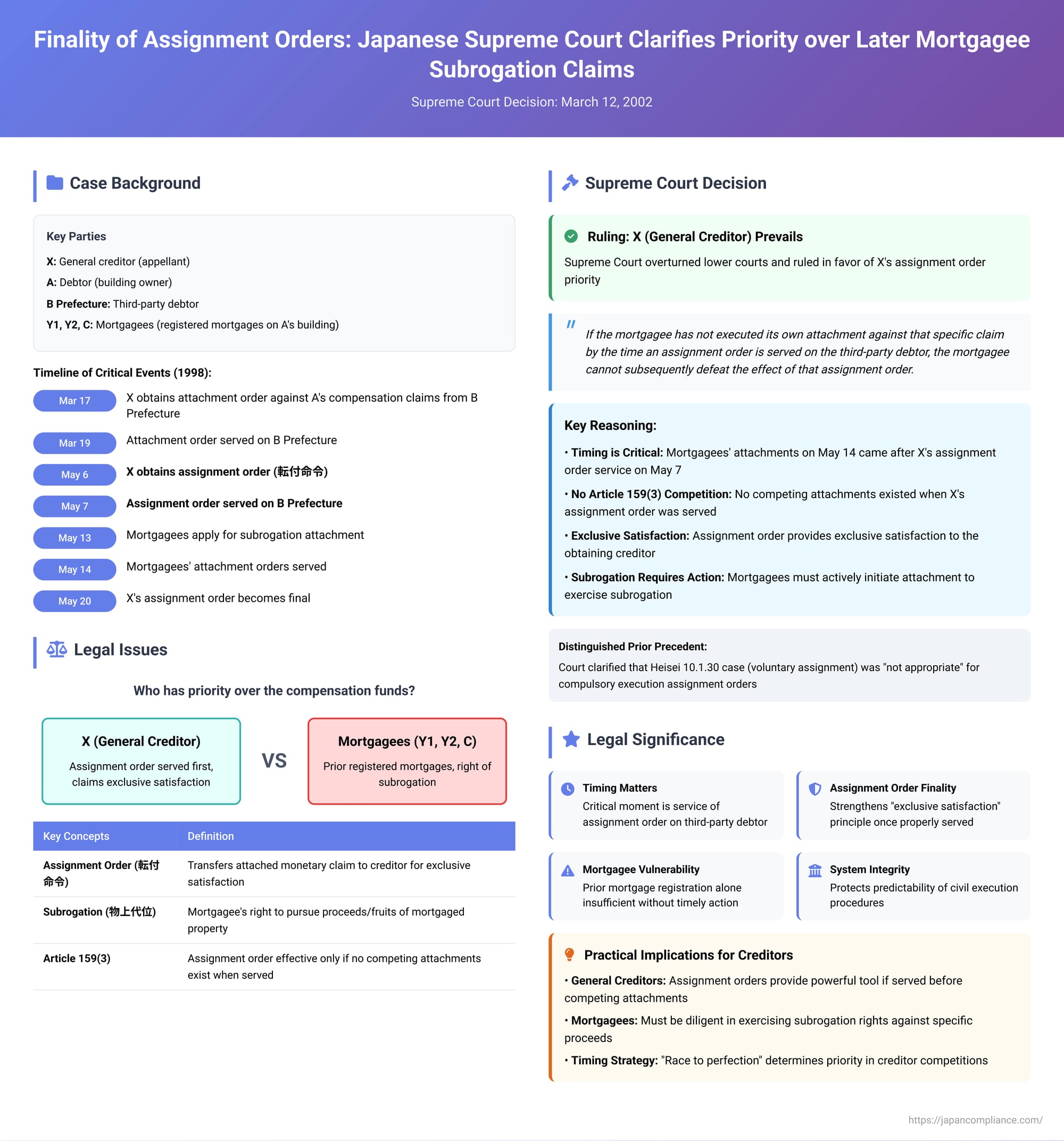

In the complex interplay of creditor rights under Japanese law, the priority between different claims on a debtor's assets is a frequently contested issue. A significant decision by the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on March 12, 2002 (Heisei 12 (Ju) No. 890), provided critical clarification on the contest between a general creditor who secures an "assignment order" (転付命令 - tempu meirei) over a monetary claim, and mortgagees who subsequently attempt to exercise their right of subrogation (物上代位 - butsujō daii) to seize the same claim. The ruling underscored the power and finality of a perfected assignment order when specific conditions are met.

The Factual Background: A Contest Over Compensation Funds

The case revolved around a compensation claim owed by B Prefecture to A for the acquisition of A's building. The key parties and events were:

- Pre-existing Mortgages: Several registered mortgages (or neteitōken, a type of floating charge mortgage) existed on A's building. These were held by C (a non-party to the appeal), Y1, and Y2 (the defendants/appellees), in that order of priority. These mortgages were duly registered before the actions of X, the general creditor.

- X's (General Creditor) Enforcement Actions: X, a general creditor of A, took steps to collect its debt:

- March 17, 1998: X obtained an attachment order from the Matsuyama District Court (Uwajima Branch) against A's monetary claims from B Prefecture. These claims consisted of land sale proceeds ("Claim 甲") and, more relevantly, the remaining compensation for the building ("Claim 乙").

- March 19, 1998: X's attachment order was served on B Prefecture (the third-party debtor).

- March 23, 1998: The order was served on A (the debtor).

- April 17, 1998: The attachment order became final and binding.

- May 6, 1998: X obtained an assignment order (tempu meirei) for the entirety of Claim 甲 and a significant portion of Claim 乙. An assignment order, under Japanese civil execution law, transfers the attached monetary claim directly from the debtor to the attaching creditor, effectively making the attaching creditor the new owner of that claim.

- May 7, 1998: This crucial assignment order was served on both B Prefecture and A.

- May 20, 1998: X's assignment order became final and binding.

- Mortgagees' Subsequent Subrogation Actions: After X's assignment order had been obtained and served:

- May 13, 1998: The mortgagees (C, Y1, and Y2) initiated their own actions. They applied to the Matsuyama District Court (Uwajima Branch) to exercise their right of subrogation under their respective mortgages against Claim 乙 (the building compensation). This right of subrogation allows mortgagees to pursue the proceeds or fruits of their mortgaged property.

- May 14, 1998: The attachment orders sought by C, Y1, and Y2 were granted and served on B Prefecture.

- Deposit and Distribution Dispute: Faced with these multiple claims, B Prefecture deposited the entire amount of Claim 甲 and Claim 乙 with the court. The execution court then prepared a distribution statement. This statement prioritized the mortgagees: C first, then Y2, then Y1 (all receiving their claimed amounts in full from Claim 乙), with X receiving the remainder from Claim 乙 and the entirety of Claim 甲 (which was not subject to the mortgages). X objected to this distribution, arguing that its perfected assignment order gave it priority over the mortgagees for the portion of Claim 乙 covered by its assignment order.

The court of first instance and the Takamatsu High Court both ruled against X, upholding the priority of the mortgagees. These lower courts relied significantly on a 1998 Supreme Court decision (Heisei 10.1.30), interpreting it to mean that a mortgagee's right of subrogation could be exercised even against a claim that had been previously assigned and the assignment perfected against third parties. They essentially held that the mortgagees' underlying security interest in the property gave them an overriding claim to its proceeds, even if a general creditor had already obtained an assignment order for those proceeds.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Clarification

The Supreme Court, in its March 12, 2002, judgment, decisively overturned the lower courts' decisions and ruled substantially in favor of X. The Court clarified the hierarchy of rights when an assignment order competes with a mortgagee's subsequent attempt at subrogation:

The Core Holding: Even if a monetary claim could potentially be subject to a mortgagee's right of subrogation, if the mortgagee has not executed its own attachment against that specific claim by the time an assignment order obtained by another creditor is served on the third-party debtor, the mortgagee cannot subsequently defeat the effect of that assignment order. Once the general creditor's attachment and assignment orders become final, the assigned claim is deemed to have been applied to the satisfaction of that creditor's debt and execution costs as of the moment the assignment order was served on the third-party debtor. Consequently, the mortgagees cannot thereafter assert the effect of their mortgages against the specific claim that has already been effectively transferred to the assignment order creditor.

Deconstructing the Supreme Court's Reasoning:

- Nature and Purpose of an Assignment Order (転付命令 - tempu meirei):

The Court began by explaining that an assignment order is a specific statutory mechanism for a creditor to realize (or "cash out") a monetary claim that has already been attached. It achieves this by legally transferring ownership of the attached claim from the original debtor to the attaching creditor. - Exclusive Satisfaction and Its Condition (Civil Execution Act Art. 159(3)):

An assignment order is designed to provide "exclusive satisfaction" to the creditor who obtains it. This means the creditor receives the full benefit of the assigned claim (up to their debt amount and costs), to the exclusion of other creditors. However, this powerful effect is conditional. Article 159, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Execution Act stipulates that an assignment order takes effect only if no other creditor has, by the time the assignment order is served on the third-party debtor, already executed an attachment, provisional attachment, or made a formal demand for distribution (配当要求 - haitō yōkyū) against the same monetary claim. - Mortgagee's Exercise of Subrogation Requires Its Own Attachment:

The Supreme Court reiterated a principle from its earlier jurisprudence (citing a Heisei 13.10.25 decision): for a mortgagee to exercise its right of subrogation against specific proceeds of the mortgaged property (like compensation payments or rent), the mortgagee must actively initiate its own attachment proceeding against those proceeds. The mortgage on the physical property does not automatically attach to its monetary proceeds without this distinct enforcement step. - Mortgagee's Attachment is Subject to General Execution Rules:

When a mortgagee initiates such an attachment as an exercise of subrogation, that attachment is governed by the same rules of civil execution as any other creditor's attachment. This includes the provisions of Article 159(3) concerning competing attachments that can prevent an assignment order from taking effect. - "Attachment" in Article 159(3) Encompasses Mortgagee's Subrogation Attachment:

The Court found it "clear from the wording" (文理上明らか - bunrijō akiraka) that the term "attachment" as used in Article 159(3) includes an attachment made by a mortgagee exercising its right of subrogation. Therefore, if a mortgagee had attached the claim before X's assignment order was served on B Prefecture, that could have been a competing attachment under Article 159(3) potentially affecting X's order. - No Special Treatment for Untimely Mortgagee Attachment:

Conversely, if the mortgagee's subrogation-based attachment occurs after a general creditor's assignment order has already been served on the third-party debtor (and no other Article 159(3) competing actions existed at that moment of service), there is no legal basis to treat the mortgagee's later attachment differently or to give it a superior effect that would retroactively invalidate the perfected assignment order. To do so, the Court stated, "would contradict the purpose for which the assignment order system was established." - Distinguishing from the Heisei 10.1.30 Precedent:

The Supreme Court explicitly addressed the lower courts' reliance on the Heisei 10.1.30 decision. It stated that the earlier case involved a different factual scenario—specifically, a voluntary assignment of a claim by the debtor themselves to a third party, which was then contested by a mortgagee's subrogation. The present case, however, involved an assignment order obtained through compulsory execution proceedings. The Court deemed the earlier precedent "not appropriate" for the current facts, thereby clarifying its scope and preventing its misapplication to assignment orders under the Civil Execution Act.

In essence, X's assignment order, having been served on B Prefecture on May 7, 1998, without any prior attachments by C, Y1, or Y2 that would trigger Article 159(3), became effective. The subsequent attachments by the mortgagees on May 14, 1998, were too late to defeat X's acquired right to the portion of Claim 乙 covered by its assignment order.

Implications of the Landmark Ruling

This 2002 Supreme Court decision has significant implications for creditors' rights and civil execution practice in Japan:

- Strengthening the Finality of Assignment Orders: The ruling robustly affirms the "exclusive satisfaction" principle of assignment orders. Once an assignment order is served on a third-party debtor, and provided no other creditor had perfected a competing attachment or demand for distribution at that precise time, the claim is effectively transferred to the assignment order creditor. This provides a degree of finality and certainty to this enforcement mechanism.

- Diligence Required from Mortgagees to Secure Proceeds: While mortgagees possess a powerful right of subrogation, this decision underscores that they must be diligent in exercising this right if they wish to secure specific monetary proceeds from their collateral. The mere existence of a registered mortgage on the primary asset (e.g., a building) does not grant an automatic or overriding claim to its proceeds (e.g., compensation or rent) against a general creditor who diligently pursues and perfects an assignment order for those proceeds first. Mortgagees must initiate their own attachment proceedings against such proceeds in a timely manner.

- Clarifying the "Race" Among Creditors: The judgment helps to clarify the rules of the "race" among creditors. For a general creditor pursuing an assignment order, the critical moment is the service of that order on the third-party debtor free of pre-existing competing attachments under Article 159(3). For a mortgagee wanting to claim proceeds via subrogation, the critical step is to execute their own attachment against those proceeds before another creditor perfects an assignment order.

- Reining in Over-Extension of the Heisei 10.1.30 Precedent: By explicitly distinguishing the facts and holding of the Heisei 10.1.30 case, the Supreme Court prevented a potentially over-broad interpretation that might have unduly favored mortgagees' subrogation rights even over judicially sanctioned assignment orders. It highlighted that the rules applicable to voluntary assignments by a debtor may not be identical to those governing compulsory execution measures like assignment orders.

- Protecting the Integrity of the Civil Execution System: The decision promotes stability and predictability within the civil execution system. If the effects of a perfected assignment order could be easily undone by the later actions of mortgagees who had not timely asserted their claims against the specific proceeds, the utility of the assignment order as an efficient debt collection tool would be significantly compromised.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's March 12, 2002, decision is a vital piece of jurisprudence in Japanese civil execution law. It establishes that a general creditor who successfully obtains an assignment order and has it served on the third-party debtor, without any other competing attachments or demands for distribution existing at that moment as defined by Article 159(3) of the Civil Execution Act, secures a definitive right to those funds. This right prevails even against mortgagees who hold prior registered mortgages on the underlying asset from which the funds were derived, if those mortgagees fail to execute their own attachment against the specific funds in exercise of their subrogation rights before the assignment order is perfected. The ruling underscores a fundamental principle: while secured rights are potent, their translation into claims on specific proceeds in a competitive creditor environment often requires timely and procedurally correct affirmative action.