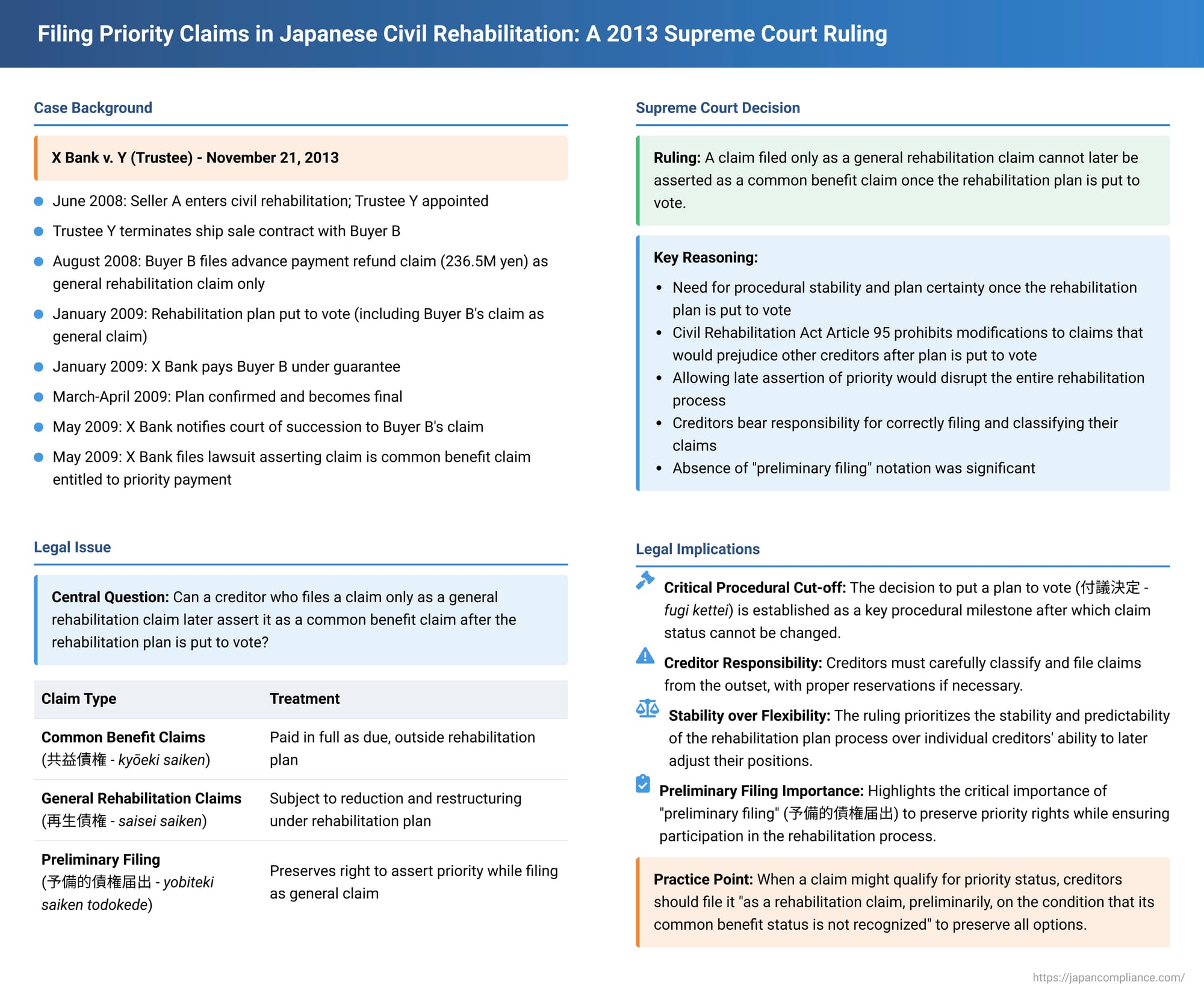

Filing Priority Claims in Japanese Civil Rehabilitation: A 2013 Supreme Court Ruling on Procedural Choices and Their Consequences

In Japanese civil rehabilitation proceedings, certain claims are designated as "common benefit claims" (共益債権 - kyōeki saiken). These claims, akin to "estate claims" in bankruptcy, are afforded priority and are generally paid in full as they become due, outside the terms of the rehabilitation plan that binds most other creditors. General "rehabilitation claims" (再生債権 - saisei saiken), by contrast, are typically subject to significant modifications, such as reductions in amount ("haircuts") and rescheduled payment terms, under an approved rehabilitation plan.

A crucial procedural question arises: What happens if a creditor holds a claim that genuinely qualifies as a priority common benefit claim but, for whatever reason, files it in the rehabilitation proceedings only as a general rehabilitation claim, without specifically noting its potential common benefit status or filing it "preliminarily" as a rehabilitation claim while reserving the right to assert its higher priority? Can such a creditor, having initially filed their claim as a general one, later change course and demand full, immediate payment as a common benefit claim, especially after a rehabilitation plan based on their initial filing has been formulated and put to a vote by creditors? A Supreme Court of Japan decision from November 21, 2013, provided a clear answer to this important practical issue.

Factual Background: A Common Benefit Claim Filed as a General Rehabilitation Claim

The case involved Seller A, a company that had contracted to sell a ship to a foreign entity, Buyer B. Buyer B had made a substantial advance payment to Seller A of 236.5 million yen ("the subject advance payment"). X Bank had issued a guarantee to Buyer B, covering Seller A's obligation to refund this advance payment if the sale did not proceed.

Subsequently, Seller A encountered financial difficulties and, on June 18, 2008, had civil rehabilitation proceedings commenced against it. Y was appointed as Seller A's trustee (under a management order, common in corporate rehabilitations). Shortly thereafter, on June 25, 2008, trustee Y, exercising powers under Article 49, paragraph 1, of the Civil Rehabilitation Act, terminated the ship sale contract between Seller A and Buyer B. This termination triggered Seller A's obligation to refund the advance payment to Buyer B. Under Japanese insolvency law (specifically, Article 49, paragraph 5, of the Civil Rehabilitation Act, which incorporates principles from Article 54, paragraph 2, of the Bankruptcy Act), such a claim for the refund of an advance payment arising from a contract terminated by the trustee generally qualifies as a priority common benefit claim.

On August 6, 2008, Buyer B filed a proof of claim in Seller A's rehabilitation proceedings for the refund of the advance payment and associated interest. However, Buyer B filed this claim solely as a general rehabilitation claim. The claim form did not include any notation or reservation indicating that it was being filed "preliminarily" as a rehabilitation claim while Buyer B intended to preserve or assert its status as a common benefit claim. Separately, X Bank also filed its own (at that point, contingent) claim for recourse against Seller A based on its guarantee to Buyer B.

During the claim investigation process, trustee Y formally acknowledged Buyer B's advance payment refund claim as filed—that is, as a general rehabilitation claim. No other creditors raised any objections to this classification. Trustee Y did, however, object to X Bank's contingent recourse claim, noting its future and conditional nature.

Based on the claims as filed and acknowledged, a proposed rehabilitation plan for Seller A was drafted. This plan treated Buyer B's advance payment refund claim as a general rehabilitation claim, subject to the plan's terms for repayment (which would typically involve less than full payment and/or deferred payments). On January 13, 2009, the rehabilitation court issued a formal decision to put this proposed rehabilitation plan to a vote by the creditors (付議決定 - fugi kettei). The plan was subsequently approved by the creditors and formally confirmed by the court on March 17, 2009, becoming legally final and binding on April 14, 2009. Notably, the confirmed rehabilitation plan stated that there were no common benefit claims due and unpaid as of December 21, 2008, and Buyer B's advance payment refund claim was explicitly listed in the schedule of general rehabilitation claims to be paid according to the terms of the plan.

After the court's decision to put the plan to a vote, on January 23, 2009, X Bank fulfilled its guarantee obligation by paying Buyer B the amount of the advance payment refund. Having done so, X Bank subrogated to Buyer B's rights against Seller A. On May 1, 2009, X Bank formally notified the rehabilitation court that it had succeeded to Buyer B's claim. Then, on May 27, 2009, X Bank initiated a separate lawsuit against trustee Y. In this lawsuit, X Bank now argued that the advance payment refund claim it held (as successor to Buyer B) was, in fact, a common benefit claim and demanded its full and immediate payment from trustee Y, outside the terms of the now-confirmed rehabilitation plan.

The Osaka District Court (first instance) dismissed X Bank's suit. While it acknowledged that, in principle, a common benefit claim mistakenly filed as a rehabilitation claim might still potentially be asserted with its priority outside the proceedings, it based its dismissal on a different ground: that X Bank, as a subrogee, could only exercise the original claim to the extent of its own recourse claim against Seller A, which it viewed as merely a general rehabilitation claim. (This specific reasoning regarding the recourse claim limiting the nature of the subrogated claim was later clarified and effectively overturned by separate Supreme Court decisions in November 2011, covered in a previous discussion, where the Court held that a subrogated priority claim retains its priority irrespective of the status of the subrogee's direct recourse claim).

The Osaka High Court also dismissed X Bank's appeal. It found that the advance payment refund claim had been definitively confirmed as a general rehabilitation claim through the claims determination process, and therefore, it could no longer be asserted as a common benefit claim seeking payment outside the rehabilitation proceedings. It also agreed with the first instance court's reasoning concerning the limitation based on X Bank's recourse claim. X Bank then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Issue: Can a Creditor Switch a Claim's Status After a Rehabilitation Plan is Put to a Vote?

The central legal question before the Supreme Court was: If a creditor holds a claim that objectively qualifies as a priority common benefit claim, but they file it in the civil rehabilitation proceedings only as a general rehabilitation claim (without any reservation, such as stating it's a "preliminary filing"), are they then bound by that classification once a rehabilitation plan, which treats their claim as a general one, is formally put to a vote by the creditors? Or can the creditor (or their subrogee) subsequently "switch hats" and demand that the claim be treated as a common benefit claim, entitled to full and immediate payment outside the terms of the rehabilitation plan?

This issue involves a fundamental tension between a creditor's substantive right to priority payment for certain types of claims and the overriding need for procedural stability, predictability, and finality in the civil rehabilitation process, particularly once a proposed plan reaches the critical stage of being presented to all creditors for a vote.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: No Switching Status After Plan is Put to Vote

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of November 21, 2013, dismissed X Bank's appeal. It held that X Bank could not, at that stage, assert the claim as a common benefit claim and demand its payment outside the rehabilitation proceedings.

The Court's core holding was:

If a person holds a claim that qualifies as a common benefit claim under the Civil Rehabilitation Act, but that claim is filed in the proceedings only as a rehabilitation claim—without any accompanying notation that it is being filed "preliminarily" as a rehabilitation claim while reserving its status as a common benefit claim—and a rehabilitation plan, drafted on the premise of this claim being treated as a rehabilitation claim, is subsequently put to a creditor vote by a formal court decision (付議決定 - fugi kettei), then that creditor (or their successor) cannot thereafter assert that the claim is a common benefit claim and demand its payment outside the rehabilitation proceedings.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was grounded in the procedural integrity and stability of the civil rehabilitation process:

- The Importance of Procedural Stability and Plan Finality: The Court emphasized the critical need to stabilize the rehabilitation proceedings and to ensure the certainty of the contents of a proposed rehabilitation plan once the court has formally decided to submit it to a vote by the creditors. This decision to put the plan to a vote (the fugi kettei) is a pivotal moment in the process.

- Effect of Civil Rehabilitation Act Article 95: The Court pointed to Article 95 of the Civil Rehabilitation Act. This article generally provides that once a decision has been made to put a rehabilitation plan to a vote, rehabilitation creditors cannot thereafter supplement their filed claims or make changes to the matters stated in their filings in a way that would prejudice the interests of other rehabilitation creditors. While this article primarily addresses modifications by creditors, the Court invoked its underlying spirit regarding the finality of the claims picture at this stage.

- Inappropriateness of Asserting a Different Status Post-Fugi Kettei: The Court reasoned that if a claim, which is inherently a common benefit claim, was filed by the creditor solely as a general rehabilitation claim (without any "preliminary filing" reservation indicating its potential common benefit nature), and the rehabilitation plan was then drafted, reviewed, and formally put to a creditor vote on that basis (i.e., treating the claim as a general one that will be dealt with under the plan's terms), it would be clearly inappropriate and highly disruptive to the entire rehabilitation process to allow the creditor to subsequently change their position and demand full, immediate payment of that same claim as a common benefit claim, entirely outside the framework of the plan that creditors are about to vote on (or have already voted on). Such a late change in assertion would fundamentally undermine the basis upon which the plan was formulated, negotiated, and presented to all stakeholders for their collective decision.

Applying this to the facts of the case, Buyer B's advance payment refund claim, although qualifying as a common benefit claim, had been filed only as a rehabilitation claim, without any reservation of its common benefit status. The rehabilitation plan for Seller A was drafted and put to a vote based on this understanding. Once that fugi kettei occurred, and especially after the rehabilitation plan was subsequently confirmed by the court and became final, X Bank (as Buyer B's successor) was barred from asserting that this same claim was a common benefit claim entitled to preferential payment outside the confirmed plan.

The Importance of "Preliminary Filing" (予備的債権届出 - yobiteki saiken todokede)

The Supreme Court's decision implicitly underscores the significance of a common practice in Japanese insolvency proceedings known as "preliminary filing" or "conditional filing" (予備的債権届出 - yobiteki saiken todokede). As noted in the PDF commentary accompanying this case, when a creditor believes their claim qualifies for a priority status (such as a common benefit claim) but there is a possibility that this status might be disputed or denied, or if they simply wish to preserve a fallback position, they will often file their claim "as a rehabilitation claim (or bankruptcy claim), preliminarily, on the condition that its common benefit (or other priority) status is not recognized." This type of conditional language in the proof of claim serves to alert the trustee/supervisor and other parties that the creditor is asserting a primary right to priority treatment but is also preserving their right to participate as a general creditor if the priority claim is not upheld. This case, where no such preliminary or conditional language was used in the filing, highlights the risks a creditor takes if they file a potentially priority claim solely as a general claim without clearly reserving their right to assert its higher status.

Implications of the Decision

This 2013 Supreme Court judgment has several important implications for creditors and insolvency practitioners in Japan:

- Establishes a Critical Procedural Cut-off: The decision effectively establishes the court's formal "decision to put the rehabilitation plan to a vote" (fugi kettei) as a critical procedural cut-off point. Before this juncture, a creditor who may have mistakenly or incompletely filed a priority claim might have more flexibility to amend their filing or clarify the claim's status. However, once the plan based on the existing filings is put to a vote, the creditor is largely bound by their initial, unqualified filing, at least for the purpose of asserting a right to payment outside the plan based on a different, unreserved status.

- Emphasizes Creditor Responsibility in Filing Claims: The ruling reinforces the principle that creditors bear the primary responsibility for correctly and fully classifying and asserting the status of their claims in insolvency proceedings. While trustees and supervisors have duties to investigate claims, they generally do not have an affirmative obligation to proactively reclassify a claim for a creditor if the creditor has unambiguously filed it under a less advantageous category without any reservation.

- Promotes Stability and Predictability in the Plan Process: The decision prioritizes the stability, predictability, and integrity of the rehabilitation plan formulation and approval process. Allowing creditors to belatedly change the asserted status of significant claims after a plan has been finalized for voting would create immense uncertainty and could derail the entire rehabilitation effort.

- Possible Application to Other Priority Claims: The PDF commentary suggests that the reasoning of this judgment, which focused on common benefit claims, would likely also apply to other types of claims that have a special status but might be mistakenly filed as general claims, such as "preferential rehabilitation claims" (優先的再生債権 - yūsenteki saisei saiken) under Article 122 of the Civil Rehabilitation Act.

- Different Considerations if Rehabilitation Fails: The PDF commentary also posits that if the civil rehabilitation proceeding itself were to be abolished (e.g., due to the inability to formulate or confirm a viable plan) and the case were to transition into a bankruptcy liquidation, the concerns about "plan stability" that underpinned this Supreme Court decision would no longer be paramount. In such a scenario, a creditor who had mistakenly filed a claim with inherent priority (e.g., one that would qualify as an estate claim in bankruptcy) only as a general rehabilitation claim might then have a renewed opportunity to assert its true priority status in the subsequent bankruptcy proceeding.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's November 21, 2013, decision sends a clear message to creditors participating in Japanese civil rehabilitation proceedings: careful and accurate claim filing is paramount. If a creditor believes their claim is entitled to priority status as a common benefit claim, they must assert that status properly and, if filing it also as a general rehabilitation claim, should strongly consider using a "preliminary filing" reservation to protect their position. Failing to do so, and allowing a rehabilitation plan to be formulated and put to a creditor vote based on the claim being treated as a general one, will likely bar the creditor from later attempting to "upgrade" the claim's status and demand preferential payment outside the plan. This ruling underscores the balance the Japanese legal system strikes between protecting legitimate priority rights and ensuring the orderly, stable, and predictable progression of collective insolvency proceedings designed to achieve debtor rehabilitation.