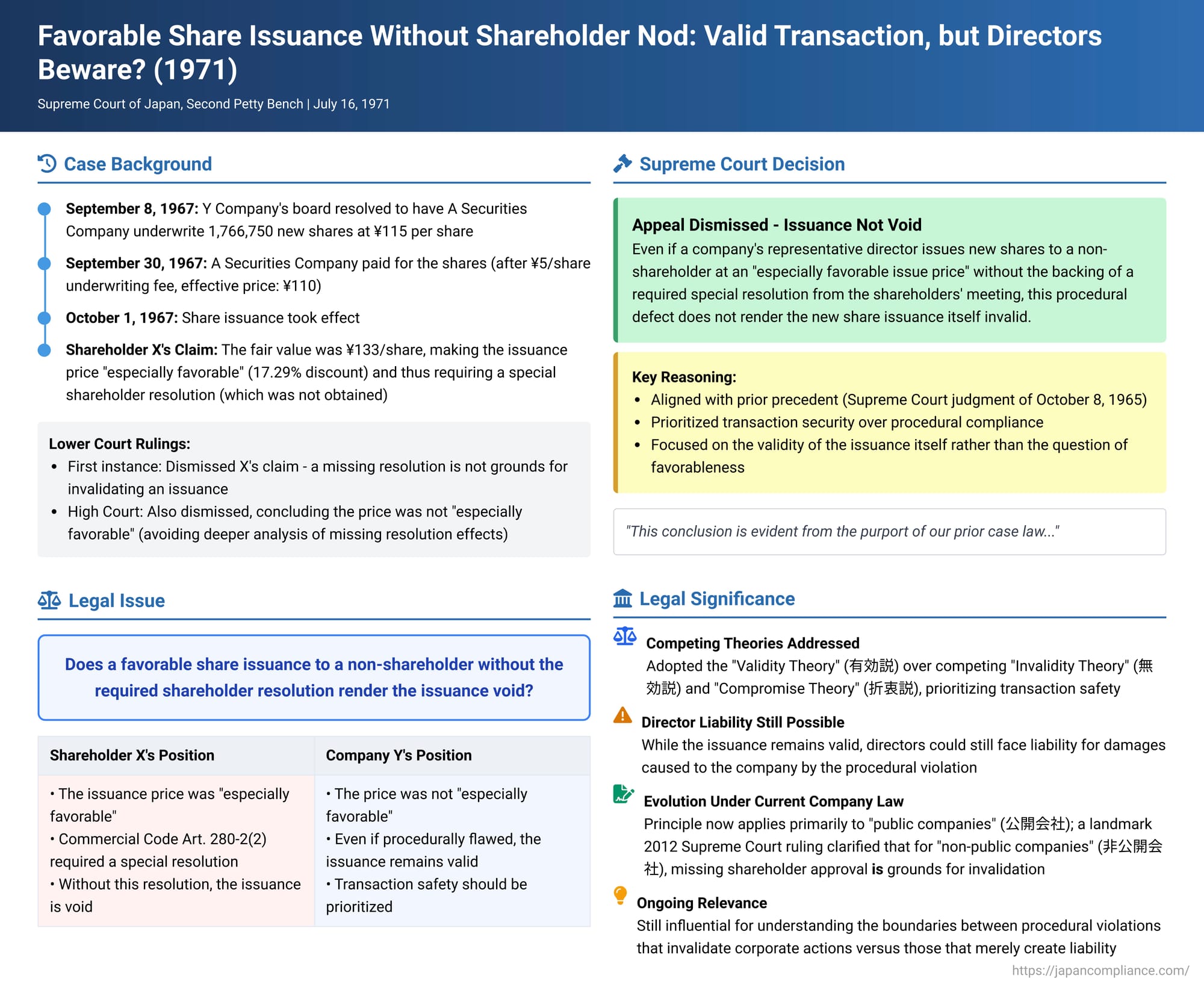

Favorable Share Issuance Without Shareholder Nod: Valid Transaction, but Directors Beware? (A 1971 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling)

Judgment Date: July 16, 1971

Case: Action for Declaration of Nullity of New Share Issuance (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

This 1971 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed a critical question in corporate law: If a company issues new shares to a third party at what is alleged to be an "especially favorable price" but fails to obtain the otherwise required special resolution from its shareholders, is the share issuance itself void? The Court's answer prioritized transactional safety over procedural defects in this context, though the landscape has since evolved.

Factual Background: A Share Issuance Challenged

The dispute involved Y Company and its shareholder, X.

- The Share Issuance: On September 8, 1967, Y Company's board of directors resolved to have A Securities Company underwrite 1,766,750 new shares at an issue price of JPY 115 per share. A Securities Company completed the payment for these shares on September 30, 1967, and the new share issuance took effect on October 1, 1967.

- Shareholder's Claim: X, who held 1,000 shares in Y Company, filed a lawsuit to nullify this new share issuance. X contended that:

- The fair value of Y Company's shares on September 7, 1967 (the day before the board resolution), was JPY 133 per share.

- The effective issue price to A Securities Company was actually JPY 110 per share, after deducting an underwriting fee of JPY 5 per share that Y Company paid to A Securities Company.

- This effective price of JPY 110 was approximately 17.29% lower than the asserted fair value of JPY 133, making it an "especially favorable issue price" for a non-shareholder.

- Under the Commercial Code then in effect (Article 280-2, Paragraph 2, which corresponds to principles in current Company Law Articles 199(3) and 201(1)), such a favorable issuance to a non-shareholder required a special resolution of the shareholders' meeting.

- Since Y Company had not obtained this special resolution, X argued the entire issuance of 1,766,750 shares was void.

- Lower Court Rulings: The court of first instance dismissed X's claim, holding that the absence of a shareholders' meeting resolution did not constitute grounds for invalidating a new share issuance. The High Court also dismissed X's appeal, primarily concluding that the JPY 115 issue price was not "especially favorable," without deeply delving into the consequences of a missing resolution had it been deemed favorable. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Procedural Flaw Does Not Invalidate Issuance

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal.

The Court's core reasoning was that even if a company's representative director issues new shares to a non-shareholder at an "especially favorable issue price" without the backing of a special resolution from the shareholders' meeting, this procedural defect does not render the new share issuance itself invalid.

The Supreme Court stated that this conclusion was evident from the purport of its own prior case law, specifically citing a Supreme Court judgment from October 8, 1965 (Minshu Vol. 19, No. 7, p. 1745). Based on this, X's claim, which centered on the argument that the lack of a special resolution made the share issuance void, was deemed unfounded.

Analysis and Implications: A Principle of Transactional Safety

This 1971 ruling was a significant statement on the robustness of new share issuances in the face of certain procedural errors, though its direct applicability has been refined by later legal developments.

1. The Core Debate: Validity of Flawed Favorable Issuances

The judgment sits within a broader debate on the consequences of issuing shares at a favorable price without full procedural compliance. Three main theories have been proposed:

- Validity Theory (有効説 - yuko setsu): The stance taken by the Supreme Court in this case and its precedents. It holds that the lack of a required special shareholders' resolution for a favorable issuance does not nullify the issuance itself. The focus is on maintaining the security of the transaction.

- Invalidity Theory (無効説 - muko setsu): This theory argues that such a procedural lack, particularly the absence of a special shareholder resolution, is a fatal flaw that renders the entire share issuance void.

- Compromise/Eclectic Theory (折衷説 - setchu setsu): This view suggests that the issuance might be treated as void if doing so would not unduly harm the safety of transactions—for example, if the shares are still held by the initial subscriber and no third-party rights have intervened.

The Supreme Court, through a line of cases leading up to this 1971 decision, consistently upheld the Validity Theory.

2. Scope of the 1971 Judgment under Current Company Law

The Japanese Company Law enacted in 2005 introduced clearer distinctions and rules, particularly concerning "public companies" (公開会社 - kokai kaisha, whose articles do not restrict the transfer of all their shares) and "non-public companies" (非公開会社 - hi-kokai kaisha, typically closely-held companies where all shares are transfer-restricted).

- For public companies, the authority to issue new shares (募集株式 - boshu kabushiki) generally rests with the board of directors. However, if the issuance is at an "especially favorable price" to third parties, a special resolution of the shareholders' meeting is required (Company Law Art. 199(2), 201(1), 309(2)(v)).

- For non-public companies, a special shareholders' resolution is generally the default requirement for any issuance of new shares to third parties (Company Law Art. 199(2), 309(2)(v)).

The question then arises: to which type of company does the principle of the 1971 judgment (that a missing shareholder resolution for a favorable issuance does not void it) apply today?

- One interpretation suggests the 1971 judgment's logic, which relied on precedents where the board had primary issuance authority under the older authorized capital system, would primarily extend to public companies under the current law. Some scholars argued that non-public companies, which are more akin to the former yugen gaisha (limited liability companies), might not need such a restrictive interpretation regarding grounds for invalidity.

- However, a landmark Supreme Court decision on April 24, 2012 significantly clarified this. The 2012 Court ruled that if a non-public company issues shares to third parties (i.e., not through a pro-rata shareholder allotment) without obtaining the necessary special shareholders' resolution (and without proper delegation of this authority to the directors), this constitutes a serious violation of law, and the defect is a ground for invalidating the share issuance. The 2012 decision explicitly stated that the reasoning of earlier precedents (like the 1961 case that underpinned the 1971 judgment) does not apply to non-public companies. The 2012 Court highlighted that for non-public companies, protecting existing shareholders' interests in their shareholding ratio is paramount, and the law provides a longer period (one year, versus six months for public companies under Company Law Art. 828(1)(ii)) to file an invalidation suit.

- Therefore, the practical effect is that the 1971 judgment's principle—that a lack of shareholder resolution for a favorable issuance is not an invalidity cause—is now largely understood to apply mainly to public companies.

3. The Question of Determining "Favorableness" First

A point of critique regarding the 1971 Supreme Court decision was that it concluded the issuance was not void without first definitively determining whether the issue price was, in fact, "especially favorable." Some commentators argued that, like the High Court, the Supreme Court should have first assessed the favorableness of the terms. Under the Validity Theory adopted by the Court, whether the issuance was favorable or not does not change the conclusion on its validity, although it remains highly relevant for other potential remedies, such as holding directors liable for any damages caused to the company.

4. Academic Perspectives on the Theories

The divergence between the Validity Theory and the Invalidity Theory often reflects differing emphasis:

- The Validity Theory tends to view the issuance of new shares as a business transaction conducted by the company's executive organs. The requirement for shareholder approval is seen as an internal control on the board's authority. Prioritizing the security and finality of transactions, this theory holds that external dealings should not be easily undone due to such internal procedural lapses.

- The Invalidity Theory, conversely, often views new share issuance as a more fundamental corporate act affecting the company's structure and shareholder rights, akin to a merger, thus requiring stricter adherence to procedural safeguards. Proponents worry that an unqualified Validity Theory might excessively empower corporate management.

The PDF commentary notes the inherent difficulty in definitively resolving these theoretical differences, as they stem from different conceptualizations of the act of issuing shares. The Compromise Theory attempts to bridge this by allowing for invalidity where third-party transactional safety is not a concern.

5. Current Status and Unresolved Issues

Following the 2012 Supreme Court decision, much of the controversy surrounding the 1971 ruling has been settled by limiting its primary application to public companies. For non-public companies, the lack of a requisite shareholder resolution for third-party share issuances is now generally considered grounds for invalidation.

However, some questions may remain, for instance:

- If a public company issues transfer-restricted shares (as a specific class of stock) under favorable terms without the necessary separate approval from that class of shareholders (as required by Company Law Art. 199(4)), would the 1971 logic still prevail, or would the courts lean towards invalidity to protect the interests of that specific class of shareholders? Some scholars argue for invalidity in such scenarios.

- Even for freely transferable shares in a public company, if they are issued favorably without a special shareholder resolution but happen to remain with the initial subscriber (thus not implicating broader transactional safety), should this scenario allow for invalidation, aligning with the Compromise Theory? The precise boundaries for when a lack of resolution leads to invalidity in public companies continue to be an area of legal discussion.

Conclusion: A Shift Towards Differentiated Approaches

The 1971 Supreme Court judgment established a significant precedent, particularly for what would now be classified as public companies, by holding that a procedurally flawed "especially favorable" issuance of new shares to a third party is not automatically void. This decision underscored a judicial inclination towards protecting the certainty of corporate transactions. However, the legal understanding has been substantially refined by the 2012 Supreme Court ruling, which carves out a different rule for non-public companies, where such defects are indeed grounds for invalidating the share issuance. This evolution reflects a more nuanced approach, differentiating between types of companies and the relative importance of shareholder control versus transactional finality. While a flawed favorable issuance in a public company may not be void, directors involved could still face liability for damages caused to the company.