Family Ties Forged Over Time: Japan's Supreme Court on Ratifying Flawed Adoptions and Third-Party Rights

Judgment Date: September 8, 1964 (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

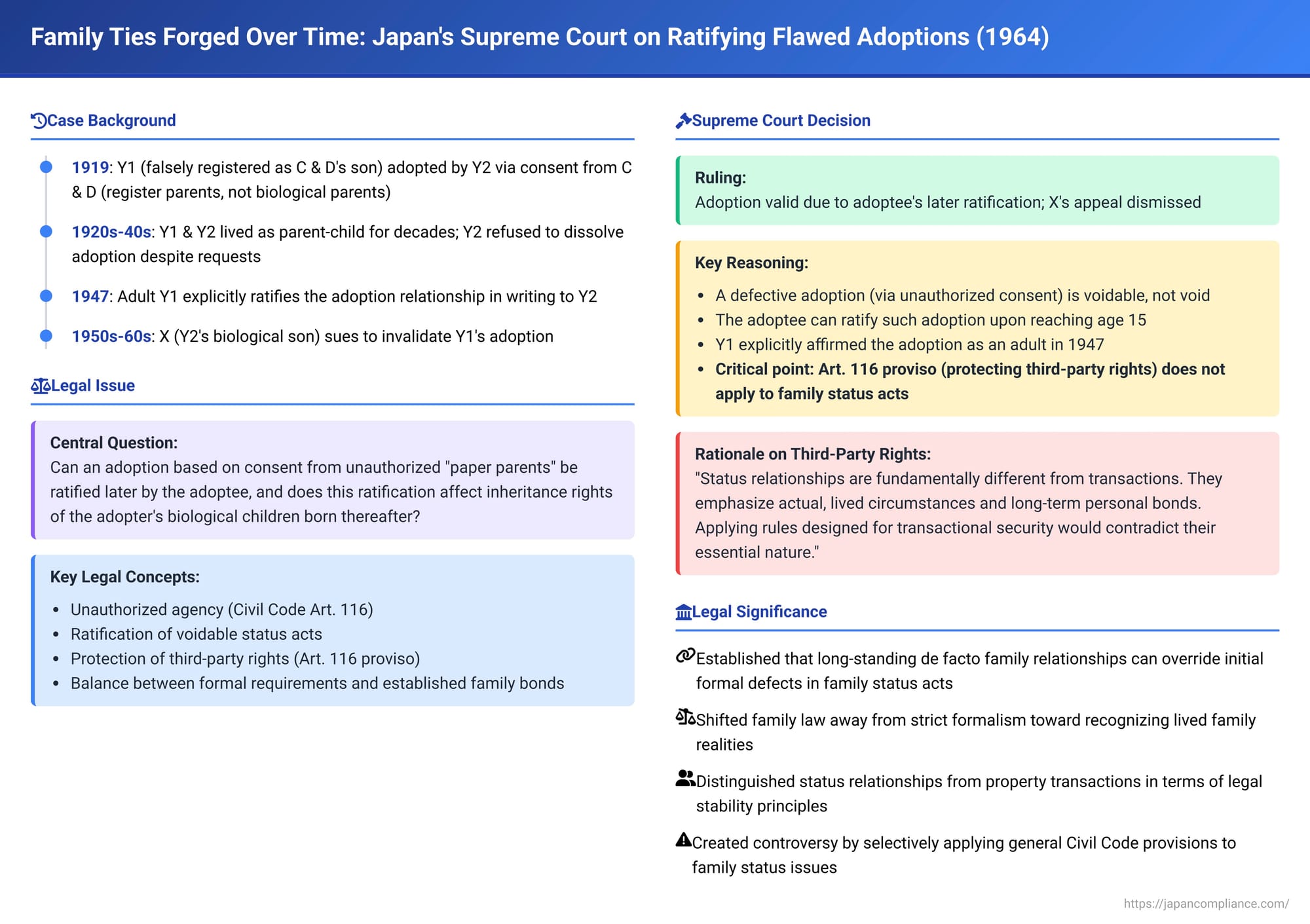

In a significant 1964 ruling, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the enduring power of established family relationships in the face of initial legal defects. The case, an "Action for Confirmation of Invalidity of Adoption" (養子縁組無効確認請求事件, Yōshi Engumi Mukō Kakunin Seikyū Jiken), concerned an adoption made decades earlier with consent provided by individuals improperly listed as parents on the family register. The Court ultimately upheld the validity of this adoption due to the adoptee's later ratification, even when challenged by an existing heir whose inheritance rights were affected, thereby emphasizing the weight given to long-standing de facto family ties in Japanese law.

A Tangled Web of Parentage and Adoption: The Facts

The story began with Y1, who was born to Mr. A and Ms. B, a couple not legally married. However, Y1 was falsely registered as the second son of a different couple, Mr. C and Ms. D. On June 9, 1919, Y1 was formally adopted by Mr. Y2 and his then-wife (referred to as Same in the judgment, who was not a party to this specific appeal).

At the time of this adoption, Y1 was under 15 years old. Consequently, the adoption required the consent of his legal parents. This consent was provided by Mr. C and Ms. D, who were Y1's parents on the family register (koseki) due to the earlier false birth registration, even though they were not his biological parents. This type of consent is known as daidaku engumi (代諾縁組), or adoption by proxy consent, typically given by parents on behalf of a minor child under 15 (as per Article 797(1) of the Civil Code).

Despite the flawed basis of the consent, Y1 and his adoptive father, Y2, lived as if they were biological parent and child for many years. When Y1 was about eight years old (around 1920), Y2 remarried after his first wife (Y1's initial adoptive mother) was no longer in the picture. Y1's biological parents, Mr. A and Ms. B, expressed concern that future conflicts might arise if Y2 had biological children with his new wife and asked Y2 to dissolve the adoption with Y1. However, Y2 refused, choosing to maintain his adoptive relationship with Y1.

The bond continued. In 1943, when Y1 departed for military service, Y2 held a celebratory send-off. In 1946, when Y1 registered his own marriage, Y2 provided his consent and covered the wedding expenses. However, a period of discord arose later that year when Y1, needing funds for a business venture, demanded property from Y2. Despite this, on December 26, 1947, Y1 (now an adult) sent a written communication to Y2, explicitly stating his intention to ratify their adoptive relationship, acknowledging its potentially irregular origins.

The legal challenge came from X, the biological son of Y2 and Y2's later wife (effectively Y1's adoptive stepbrother). X filed a lawsuit seeking to have the 1919 adoption of Y1 declared invalid. X's argument was that Mr. C and Ms. D, being only Y1's parents on paper and not his true biological parents, had no legal authority to consent to Y1's adoption in 1919, rendering the adoption void from the outset.

The Legal Saga: From Invalidity to Ratification and a Second Appeal

The case had a complex procedural history:

- Initial Lower Court Rulings: The first instance court and the initial appellate court both sided with X, declaring the adoption invalid. They reasoned that only the true biological parents could provide valid proxy consent for a minor's adoption and that the principles of ratifying an act performed by an unauthorized agent did not apply to highly formal status acts like adoption.

- First Supreme Court Intervention (1952): This was not the first time this adoption dispute reached the Supreme Court. In an earlier landmark decision on October 3, 1952 (Minshu Vol. 6, No. 9, p. 753), the Supreme Court had overturned these initial lower court rulings. The 1952 Supreme Court held that even though adoption is a formal act, the Civil Code itself allows for informal ratification of a merely voidable adoption. Therefore, an adoption based on proxy consent from an unauthorized person (like C & D) was not automatically and irretrievably void. The Court reasoned that the adoptee (Y1), upon reaching the age of 15, could ratify such an initially defective adoption. It found that the principles governing ratification of an act by an unauthorized agent (specifically Civil Code Article 116) could be applied by analogy. This ratification could be express or implied and did not require a specific formality. The 1952 decision remanded the case for reconsideration.

- Appellate Court Ruling (After Remand): Following the Supreme Court's 1952 directive, the appellate court reconsidered the case. It found that Y1 had indeed validly ratified the adoption after reaching the age of 15. Consequently, the adoption was deemed to have become valid from its inception, and X's claim for invalidity was dismissed.

- X's Second Appeal to the Supreme Court (The Current 1964 Case): X appealed again. This time, X's main argument centered on Civil Code Article 116, specifically its proviso. This proviso states that the retroactive effect of ratifying an unauthorized agent's act cannot prejudice the rights acquired by third parties in the interim. X argued that he, as Y2's legitimate biological son, had acquired the rights of an heir before Y1's ratification of the adoption took effect. Therefore, Y1's ratification, if given retroactive effect, would improperly harm X's established inheritance rights.

The Supreme Court's 1964 Decision: Ratification Upheld, Third-Party Rights Not a Bar in This Context

The Supreme Court, in its September 8, 1964 decision, dismissed X's appeal. It upheld the validity of the adoption due to Y1's ratification and specifically rejected X's argument concerning the protection of his rights under Article 116 proviso.

The Court's reasoning was:

- Article 116 Proviso Does Not Apply to Status Acts Like Adoption Ratification: The premise of X's argument was that the proviso of Civil Code Article 116 (protecting third-party rights) should apply to the ratification of an adoption. The Supreme Court disagreed. It held that for status acts such as the ratification of an adoption, the proviso of Article 116 is not applied by analogy.

- Reasoning Based on the Nature of Status Relationships: The Court explained that the proviso in Article 116 is designed to ensure the security and predictability of transactions, particularly in property law. However, status relationships (like parent-child relationships) are fundamentally different. They are characterized by their emphasis on actual, lived factual circumstances and long-term personal bonds. To apply a rule designed for transactional security to these inherently personal and factual status relationships would contradict their essential nature.

Therefore, the High Court (after the 1952 remand) was correct in not applying the Article 116 proviso when it found the adoption validated by Y1's ratification.

Significance: Upholding Long-Standing Family Ties Despite Formal Defects

This 1964 Supreme Court decision, building upon its pioneering 1952 ruling in the same case, was of immense importance. It solidified a significant shift in Japanese family law away from an overly strict adherence to formal requirements for status acts, especially when confronted with decades of de facto family life.

- Prioritization of Factual Relationships: The rulings demonstrated a judicial willingness to find ways to validate long-standing parent-child relationships even if the initial legal formalities were flawed, particularly when the individual whose status was in question (the adoptee Y1) himself affirmed the relationship upon reaching maturity.

- Overturning Strict Precedent: The 1952 decision, in particular, had overturned earlier Daishin'in (pre-WWII Supreme Court) precedents that had tended to declare adoptions based on improper proxy consent as absolutely and irremediably void. The perceived injustice of such a rigid approach, especially when it severed deeply established family ties, had long been a point of criticism.

The Theoretical Underpinnings: Unauthorized Agency and Its Application to Family Law

While the outcome—validating the adoption—received broad support due to the nearly 30-year de facto parent-child relationship between Y1 and Y2, the Supreme Court's specific theoretical pathway (analogous application of unauthorized agency rules) sparked considerable academic discussion and critique:

- The Unauthorized Agency Analogy: The Court, in its 1952 decision, chose to validate the adoption by analogously applying Civil Code Article 116, which deals with the ratification of acts performed by an unauthorized agent. This allowed Y1's later affirmation to cure the initial defect of C & D (his Koseki parents) lacking true authority to consent.

- Criticism: Some scholars argued that agency principles, designed primarily for property and commercial transactions, are not well-suited to intensely personal status acts like adoption. They might have preferred a broader theory allowing for the ratification of invalid status acts in general, recognizing their unique characteristics where lived realities often follow or solidify informal beginnings.

- Alternative Construction: Some commentators suggested that if Y1's true biological parents (A and B) had substantively consented to the adoption at the time (even if not formally named), the adoption might have been considered valid from the outset, rendering the complex ratification theory unnecessary.

- The Non-Application of Article 116 Proviso (the 1964 focus): The 1964 decision's refusal to apply the proviso of Article 116 (which protects third-party rights from the retroactive effect of ratification) was particularly controversial.

- Court's Rationale: The Court reasoned that the proviso aims to protect the security of transactions, a concern it deemed contrary to the nature of status relationships that emphasize factual realities.

- Academic Critique: This was sharply criticized by some as "arbitrary." They pointed out that family law itself contains provisions that protect third-party rights from the retroactive effects of status changes (e.g., Civil Code Article 784 concerning acknowledgment of paternity). If the main part of Article 116 was applied by analogy to allow ratification, it was argued that the proviso should logically follow.

- Counter-Argument on "Third-Party Rights": However, even if the proviso had been applied, it was debatable whether X (Y2's biological son) would have qualified as a "third party" whose vested rights were infringed by Y1's ratification. At the time of ratification, X likely only possessed an expectancy of inheritance from Y2, not a definitively acquired property right that the proviso typically protects.

Alternative Legal Perspectives

Legal commentators also explored other ways the case could have been approached:

- Restricting Who Can Challenge an Adoption: Some scholars argued that third parties like X, who were not directly involved in the original adoption process, should have limited standing to challenge a formally registered adoption that had been lived out as a de facto reality for many decades, especially when the adoptee himself wished to uphold it.

Broader Implications: Status Acts, Formalities, and General Legal Principles

The 1964 Supreme Court decision is a key case in understanding the complex relationship between the general principles of the Civil Code (often found in its General Part, like agency rules) and the specific rules governing family law status acts. While some General Part provisions are explicitly excluded from application to certain family law matters (e.g., rules on legal capacity do not fully apply to marriage or divorce), the applicability of others often requires careful, individualized consideration, as demonstrated by the Court's selective application of Article 116 in this instance.

This case, particularly when read with its 1952 precursor, highlights a tension in Japanese law between upholding prescribed legal formalities for acts like adoption and recognizing the profound social and personal realities created by long-term family relationships. It shows a judicial inclination to favor the latter when strict adherence to form would lead to results perceived as unjust or disruptive of established lives.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Lived Realities in Family Law

The Supreme Court's 1964 decision in this adoption case ultimately affirmed the power of an adoptee's ratification to cure initial defects in the consent process, especially when buttressed by decades of a lived parent-child reality. By declining to apply the third-party protection proviso of Article 116 to this status act, the Court signaled a prioritization of the substantive, factual nature of family relationships over rules designed for the security of commercial transactions. This ruling, while generating academic debate on its theoretical underpinnings, stands as a significant example of the Japanese judiciary's efforts to achieve equitable outcomes in complex family law disputes, ensuring that deeply established personal ties are not easily severed by remote formal flaws, particularly when challenged by those whose primary claim arises later. It underscores a legal philosophy that, in matters of family status, the lived truth of relationships can, under certain conditions, mend imperfections in their formal origins.