Fame Beyond Consumers: Japan's Supreme Court on Protecting "Famous Abbreviations" in Trademarks (Kokusai Jiyu Gakuen Case)

Judgment Date: July 22, 2005

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 16 (Gyo-Hi) No. 343 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

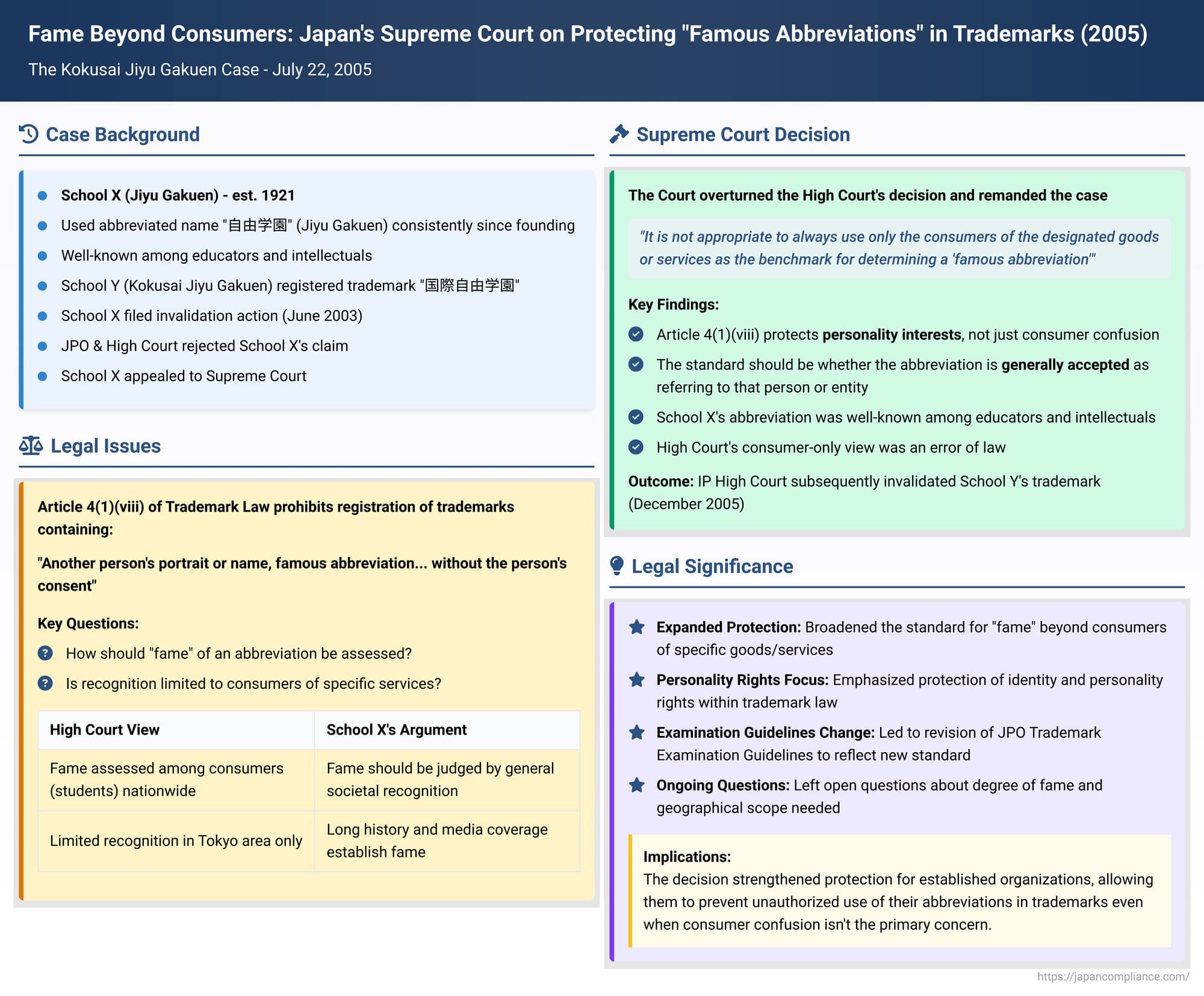

In a significant ruling that refined the protection of personality rights within trademark law, the Japanese Supreme Court in the "Kokusai Jiyu Gakuen" case addressed the crucial question of how to assess the "fame" of an abbreviation under Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 8 of the Trademark Law. This provision restricts the registration of trademarks containing another person's name or their famous abbreviation without consent. The Court notably broadened the standard for determining fame, moving beyond a narrow focus on the consumers of specific goods or services to a more general standard of societal acceptance.

The Factual Matrix: A Dispute Over "Jiyu Gakuen"

The appellant, School X (Gakko Hojin Jiyu Gakuen), is an educational institution with a long history, having been established in 1921 in Mejiro, Tokyo, initially as a secondary school for girls. Over the decades, it expanded significantly, adding an elementary division, relocating to Higashi-Kurume City in Tokyo, and establishing a boys' division, a kindergarten ("Yoji Seikatsu Dan"), and a higher education department, evolving into a comprehensive educational institution offering a consistent educational path. Since its founding, School X has used the abbreviated name "自由学園" (Jiyu Gakuen – "Abbreviation X") in connection with its educational activities and related services.

The appellee, School Y, is another school corporation, based in Kobe, which operates a business vocational school under the name "国際自由学園" (Kokusai Jiyu Gakuen, meaning International Freedom Academy). School Y is the owner of a registered trademark for the characters "国際自由学園" written horizontally. This trademark, applied for on April 26, 1996, and registered on June 5, 1998, designated services such as "teaching of arts, sports or knowledge; providing information on research materials and agency services therefor; [and] planning, management or holding of seminars".

From its early days up to the time of School Y's trademark application, School X and its Abbreviation X were frequently featured in various media, including books, newspapers, magazines, and television programs. Due to its unique history—founded by pioneering female thinker Hani Motoko and her husband Yoshikazu based on Christian and liberal educational ideals—and its distinctive educational philosophy, Abbreviation X had become well-known among education professionals and intellectuals. However, its recognition among students, prospective students, and their parents (collectively referred to as "students, etc.") at the time of the trademark application was largely confined to Tokyo and its surrounding suburbs; it had not achieved broad, nationwide周知性 (well-known status) among this specific demographic.

On June 2, 2003, School X filed for an invalidation trial against School Y's trademark. The primary argument was that the trademark "国際自由学園" contained "自由学園" (Abbreviation X), which School X asserted was a famous abbreviation of its name, thereby rendering the trademark unregistrable under Article 4(1)(viii) of the Trademark Law.

The Japan Patent Office (JPO) dismissed School X's request on March 15, 2004. School X then appealed this decision to the Tokyo High Court (which later became the Intellectual Property High Court). The High Court also dismissed School X's claim. Its reasoning was that:

- The trademark "国際自由学園" would generally be perceived by consumers as an indivisible mark representing a school's name.

- Abbreviation X ("自由学園"), when considered in relation to the relevant consumers for the designated services (i.e., students, etc., across the nation), had only achieved a certain level of name recognition within Tokyo and its vicinity. It was not widely known across a broader geographical area among these consumers.

- Therefore, students, etc., encountering the trademark "国際自由学園" would not have their attention drawn specifically to the "自由学園" portion and recognize it as containing the (limitedly) famous abbreviation of School X.

School X further appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Intervention: Redefining the Standard of Fame

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further consideration. The judgment provided a crucial clarification on the interpretation and application of Article 4(1)(viii), particularly concerning the standard for determining when an abbreviation is "famous."

Core Reasoning of the Supreme Court:

- Purpose of Article 4(1)(viii) - Personality Rights: The Court began by emphasizing the distinct purpose of Article 4(1)(viii). Unlike other provisions in Article 4(1) (such as items 10 and 15) that aim to prevent confusion regarding the source of goods or services among consumers, Article 4(1)(viii) is designed to protect the personality interests (人格的利益 - jinkakuteki rieki) associated with a person's (including legal entities like corporations and school foundations) portrait, name, famous abbreviation, etc.. This means that individuals and entities have a protected interest in not having their names or likenesses used in trademarks without their consent.

- Protection of Abbreviations: The Court reasoned that abbreviations, when generally accepted as referring to a particular person or entity, function similarly to full names and thus deserve a comparable level of protection.

- The Standard for "Famous Abbreviation": This was the central point of the judgment. The Supreme Court declared that in determining whether an abbreviation of a person's name qualifies as a "famous abbreviation" under Article 4(1)(viii), it is not appropriate to always use only the consumers of the designated goods or services of the challenged trademark as the benchmark.

- Instead, the determination should be based on whether the abbreviation is generally accepted as referring to that person (the entity whose abbreviation it is)..

- Application to the Case Facts: The Supreme Court noted that School X had used Abbreviation X ("自由学園") in connection with its educational services for a very long period. During this time, it had been frequently featured in books, newspapers, and other media, where Abbreviation X was used to identify it. The High Court itself had acknowledged that Abbreviation X was well-known among education professionals and intellectuals. Based on these facts, the Supreme Court found that there was "room to conclude that Abbreviation X was generally accepted as referring to School X".

- Error of the High Court: Consequently, the Supreme Court held that the High Court's decision—which denied a violation of Article 4(1)(viii) primarily because Abbreviation X was not widely known among the specific consumers of the designated services (students, etc.)—constituted an error in the interpretation and application of the law.

Outcome on Remand:

The case was sent back to the Intellectual Property High Court. On December 27, 2005, the IP High Court, applying the Supreme Court's standard, found that Abbreviation X ("自由学園") was indeed generally accepted as referring to School X and was therefore "famous" under Article 4(1)(viii). The IP High Court canceled the JPO's earlier decision. Subsequently, on July 18, 2006, the JPO issued a trial decision invalidating School Y's trademark registration, and this invalidation became final.

Why This Standard Matters: Personality Rights at the Forefront

The Supreme Court's decision firmly placed the protection of personality rights at the center of the inquiry for Article 4(1)(viii). This distinguishes it from other trademark provisions focused on preventing consumer confusion. The rationale is that an entity's name or its recognized abbreviation carries an intrinsic value and identity that should not be commercially exploited by others without permission, irrespective of whether such use immediately confuses consumers about service origins.

This aligns with a trend in Japanese case law and scholarly opinion that views Article 4(1)(viii) as safeguarding these personal, reputational, and identity-based interests. The fact that the provision allows for registration with the consent of the named party, and that invalidation claims under it are subject to a statute of limitations, further supports this "personality rights" interpretation.

Delving Deeper into "Famous Abbreviation"

- What is an "Abbreviation" for an Entity? For legal entities like corporations, an "abbreviation" often refers to the distinctive part of the name once legally required identifiers (like "Kabushiki Kaisha" or, in this case, "Gakko Hojin") are removed. The earlier "Tsuki no Tomo" case (Supreme Court, 1982) established this for "Kabushiki Kaisha". In the present case, "自由学園" (Jiyu Gakuen) was treated as the abbreviation of "学校法人自由学園" (Gakko Hojin Jiyu Gakuen), making its fame the critical issue.

- The Shift in Assessing Fame: The most significant aspect of the Kokusai Jiyu Gakuen ruling is the shift away from a strictly consumer-centric view of fame for abbreviations under Article 4(1)(viii).

- Previous JPO Trademark Examination Guidelines had suggested that the "degree of fame" should consider the relationship with the specific goods or services.

- The Supreme Court's directive to consider whether the abbreviation is "generally accepted as referring to that person" broadens this scope considerably. This approach had precedents in some lower court decisions (e.g., the Rikio case and the CECIL McBEE case, which used "the general public" - seken ippan - as a standard), although the Supreme Court in this instance did not use the qualifier "widely" (hiroku) known, which those lower court cases had employed.

- Impact on Examination Guidelines: The Supreme Court's stance prompted a revision of the JPO's Trademark Examination Guidelines. The revised guidelines (e.g., 13th Edition, effective April 1, 2017) now state that "In determining whether an abbreviation... is 'famous'... it is not necessarily required to use only the consumers of the designated goods or services... as the standard, from the viewpoint of protecting personality rights". This directly reflects the Court's reasoning.

Unresolved Questions and Scholarly Discourse

While the Supreme Court's decision provided significant clarity on the personal scope for judging fame (i.e., not just consumers of the specific services), it also left some questions open for further debate and interpretation:

- "Degree" and "Geographical Scope" of Fame: The ruling did not explicitly define how famous an abbreviation must be to be "generally accepted," nor did it specify the geographical extent of such recognition (e.g., local, regional, or national). Scholarly opinions on the necessary "degree of fame" vary, with some suggesting a level where society generally identifies the specific entity through the abbreviation, and others proposing a level comparable to, or even exceeding, the "widely recognized among consumers" standard required for different provisions like Article 4(1)(x). While some older lower court cases had insisted on national fame, the Supreme Court in this case (and in Tsuki no Tomo) did not explicitly address this, and many scholars argue that national fame should not be a strict requirement.

- Meaning of "Generally Accepted": The term "generally accepted" itself requires further interpretation. Who constitutes the "general" public in this context? How does this "general" group relate to or differ from the "consumers" relevant in other trademark contexts? These questions remain subjects of ongoing discussion.

- The Issue of "Containment": Another subtle legal point, not deeply analyzed by the Supreme Court in this specific judgment but relevant to Article 4(1)(viii) cases, is whether a trademark legally "contains" an abbreviation. This involves determining if the portion in question is objectively perceived as the other entity's abbreviation and if it actually evokes that entity in the minds of the relevant public. The Supreme Court in this case appeared to assume that "国際自由学園" clearly "contained" School X's abbreviation "自由学園" without extensive deliberation on this "containment" aspect itself.

Conclusion

The Kokusai Jiyu Gakuen Supreme Court decision marked an important evolution in the protection of personality rights within Japanese trademark law. By establishing that the fame of an abbreviation under Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 8 should be judged not solely by its recognition among consumers of the specific goods or services but by whether it is "generally accepted as referring to that person," the Court broadened the protective scope of this provision. This landmark ruling underscores the idea that an entity's identity, as embodied in its name and recognized abbreviations, holds a value that warrants protection against unauthorized commercial use, even beyond immediate concerns of consumer confusion. While the decision provides a clearer directional framework, the precise contours of "general acceptance" and the required "degree of fame" continue to be refined through practice and scholarly debate.