Fair Share or Fair Price? A Japanese Supreme Court Landmark on Partitioning Co-owned Property

Date of Judgment: October 31, 1996

Case Name: Claim for Confirmation of Share Rights and Partition of Co-owned Property

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

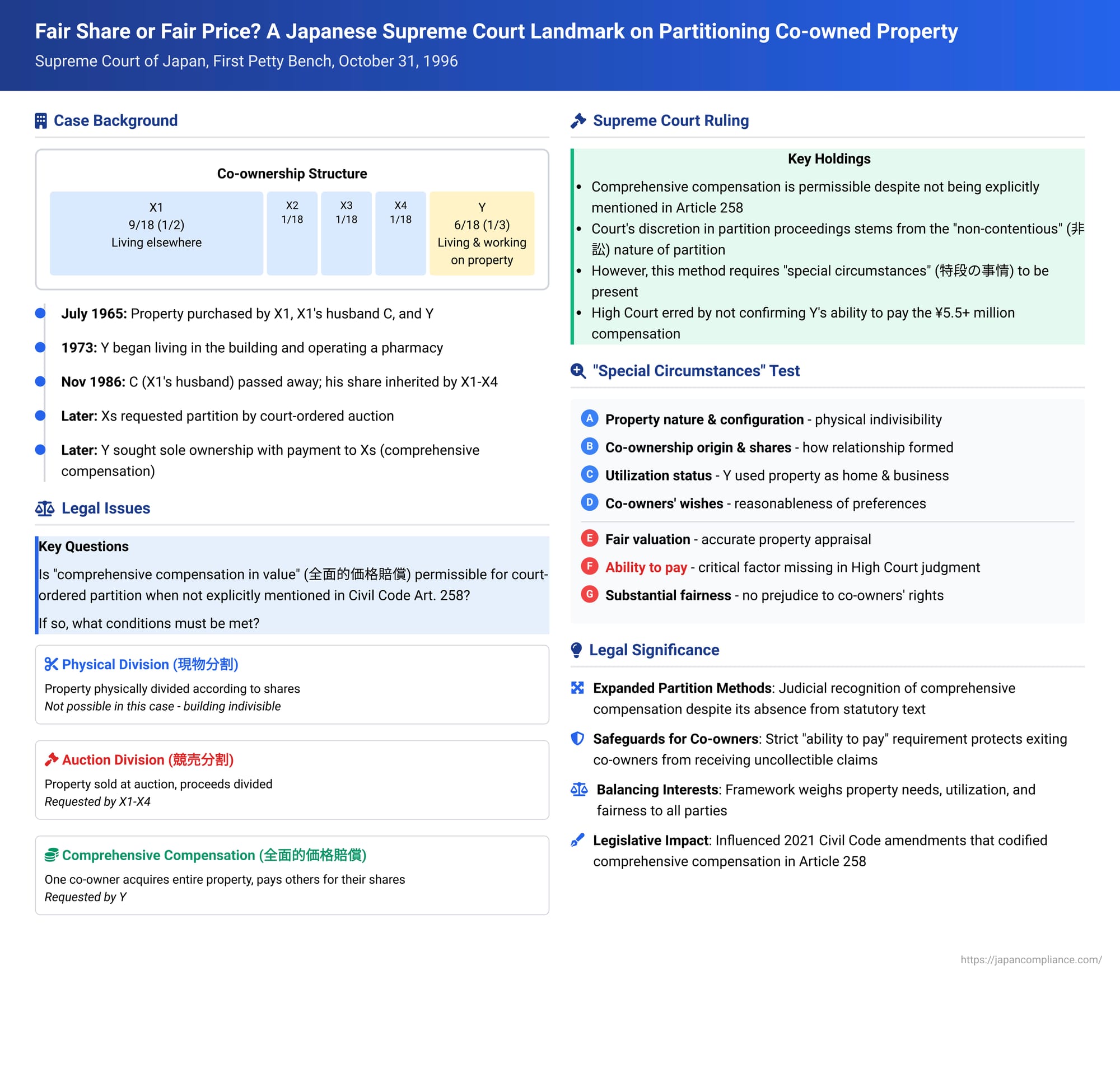

The division of co-owned property can be one of the most contentious issues in property law, particularly when co-owners have differing needs, desires, and emotional attachments to the asset. In Japan, the Civil Code provides mechanisms for partitioning such property, but the specific methods and the court's discretion in applying them have been subjects of significant legal evolution. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on October 31, 1996, profoundly shaped this area by formally recognizing a method known as "comprehensive compensation in value" (zenmenteki kakaku baishō) as a permissible means for court-ordered partition, even when not explicitly detailed in the statute at the time. This case not only broadened the judiciary's toolkit but also established crucial safeguards to ensure fairness among co-owners.

The Factual Background: A Family Property Dispute

The dispute centered around several plots of land and a building thereon (collectively, the "Property") located in Hagi City. The Property had historical ties to the family of A and B.

- The Genesis of Co-ownership: In July 1965, the Property, which had once belonged to A and his ancestors, was bought back from H Credit Union, where title had temporarily resided[cite: 1]. The purchasers were A and B's eldest daughter, X1 (an appellant), X1's husband C (who was also the adopted son of A and B), and A and B's second daughter, Y (the original appellee)[cite: 1]. Each of these three individuals acquired a one-third share in the Property[cite: 1].

- Shifting Shares Through Inheritance: In November 1986, C passed away[cite: 1]. His one-third share was inherited by his wife, X1, and their children, X2, X3, and X4 (the other appellants), according to their statutory inheritance portions[cite: 1]. This redistribution resulted in the following shareholdings:

- X1: 9/18 (or 1/2)

- X2, X3, X4: each 1/18

- Y: 6/18 (or 1/3) [cite: 1, 2]

- The Nature of the Property: The Property comprised three parcels of land almost entirely covered by a single, structurally integrated building[cite: 1]. This physical characteristic made it impossible to divide the Property into separate, physically distinct portions that would correspond to the co-owners' shares—a method known as genbutsu bunkatsu (physical division)[cite: 1]. For instance, creating separate condominium-style units reflecting their shares was not feasible[cite: 1].

- Diverging Co-owner Circumstances: Y had lived in the building on the Property since 1973[cite: 1]. She also operated a pharmacy in a part of the building (a connected single-story structure) to earn her livelihood[cite: 1]. This situation had continued for years without any significant dispute with X1 and her family[cite: 1]. In contrast, X1, X2, X3, and X4 (the Xs) all resided elsewhere and did not have a pressing need to acquire or occupy the Property[cite: 1].

- The Impasse and Lawsuit: The Xs wished to resolve the co-ownership. When discussions with Y regarding partition failed, the Xs filed a lawsuit[cite: 1]. They requested that the Property be partitioned by way of a court-ordered auction (kyōbai bunkatsu), with the proceeds to be divided according to their respective shares[cite: 1]. Y, on the other hand, desired a different outcome: she wished to obtain sole ownership of the Property and, in return, pay the Xs the monetary value of their shares[cite: 1]. This method is known as zenmenteki kakaku baishō (comprehensive compensation in value).

- Property Valuation: An expert appraisal conducted during the High Court proceedings valued the Property at a total of ¥8,263,000[cite: 1]. It was considered unlikely that an auction would achieve a significantly higher price[cite: 1]. The combined value of the Xs' shares (12/18 or 2/3 of the total) was thus in excess of ¥5.5 million.

The Journey Through the Courts

The case took the following path through the lower courts:

- The District Court: The court of first instance sided with the Xs. It rejected Y's argument that the Xs' demand for partition constituted an abuse of rights and ordered the Property to be sold at auction, as requested by the Xs[cite: 1].

- The High Court (Hiroshima High Court): Y appealed to the High Court. The High Court took a significantly different approach. First, it affirmed that "comprehensive compensation in value" could be a permissible method for court-ordered partition under Article 258 of the Civil Code (as it stood before the 2021 amendments)[cite: 1]. Second, applying this to the facts, the High Court found it appropriate to award sole ownership of the Property to Y, ordering her to pay the Xs the value of their respective shares[cite: 1]. The High Court's reasoning emphasized Y's long-term residence and business operation on the Property, the Xs' lack of direct need for it, and the low probability of a higher sale price at auction[cite: 1]. This decision was then appealed by the Xs to the Supreme Court.

The Xs argued that the High Court had erred in its interpretation and application of Article 258 of the Civil Code concerning the methods of partition[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court's Decision (October 31, 1996)

The Supreme Court's First Petty Bench delivered a nuanced judgment, agreeing with one part of the High Court's reasoning but disagreeing with its ultimate application.

1. Permissibility of Comprehensive Compensation in Value:

The Supreme Court first addressed the fundamental question of whether comprehensive compensation in value was a legally permissible method for court-ordered partition. At the time, Article 258, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code stipulated that if physical division was impossible or would significantly diminish the property's value, the court could order an auction. The provision did not explicitly mention awarding the property to one co-owner in exchange for monetary compensation to others.

Despite this textual omission, the Supreme Court affirmed that comprehensive compensation is a permissible method[cite: 1]. Its reasoning was based on the inherent nature of court-ordered partition proceedings:

"The partition of co-owned property by a court is to be deliberated and determined through the procedures of a lawsuit under civil procedure. However, its essence is that of a non-contentious matter (hishō jiken), and it is considered that the law anticipates the realization of a fair and reasonable partition, appropriate to the nature of the co-owned property and the actual state of the co-ownership, through the exercise of the court's appropriate discretion. Therefore, the aforementioned provision [Article 258(2) of the pre-amendment Civil Code] is not to be construed as intending to limit the methods of partition in all cases solely to physical division or division by auction, and to negate all other methods of partition." [cite: 1]

This marked a significant development, as it judicially endorsed a flexible approach, allowing courts to look beyond the explicitly listed methods to achieve equitable outcomes. The Court also noted its prior Grand Bench decision (April 22, 1987), which allowed for monetary payments to adjust discrepancies in value when performing physical division (a form of partial compensation), indicating a trend towards more adaptable partition solutions[cite: 1].

2. Strict Conditions ("Special Circumstances") for Comprehensive Compensation:

While affirming its permissibility, the Supreme Court emphasized that comprehensive compensation could not be ordered without restriction. It laid out a stringent set of conditions, terming them "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō), that must be met:

The Court stated that comprehensive compensation is permissible when:

"...taking into comprehensive consideration circumstances such as (a) the nature and configuration of the said co-owned property, (b) the cause of the co-ownership relationship, the number of co-owners and the ratio of their shares, (c) the utilization status of the co-owned property and its economic value if partitioned, and (d) the wishes of the co-owners regarding the method of partition and the reasonableness thereof, it is deemed appropriate to have one of the co-owners acquire the said co-owned property, AND (e) its value is appropriately appraised, (f) the co-owner acquiring the said co-owned property has the ability to pay, and (g) awarding the property to that co-owner while having them pay the value of the shares to the other co-owners is found not to harm substantial fairness among the co-owners." [cite: 1] (Lettering added for clarity).

These conditions essentially create a two-pronged test:

- Reasonableness of Awarding to a Specific Co-owner: This involves a holistic assessment of various factors related to the property and the co-owners.

- Ensuring Substantial Fairness: This focuses on the financial aspects—fair valuation, the acquirer's solvency, and the overall equity of the outcome.

3. Application to the Case and the Flaw in the High Court's Judgment:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found that while some factors might lean towards Y acquiring the property (physical division was impossible, Y considered it her home and place of business, the Xs lived elsewhere and preferred an auction), the High Court had failed critically on one point[cite: 1].

"However, as stated above, partition of co-owned property by the method of comprehensive compensation in value is permissible only when substantial fairness among the co-owners is not thereby harmed, and for that purpose, it is necessary that the person who bears the obligation to pay the compensation money has the ability to pay. According to the results of the appraisal conducted in the original instance, the total value of the appellants' [Xs'] shares is over 5,500,000 yen, but the original instance court did not make any finding of fact that Aiko [Y] had the ability to pay that amount." [cite: 1]

The Supreme Court concluded that without a factual determination of Y's ability to pay the substantial compensation owed to the Xs, the "special circumstances" justifying comprehensive compensation could not be deemed to exist[cite: 1]. The High Court's failure to investigate and confirm Y's financial capacity was a fatal flaw.

4. Outcome:

Consequently, the Supreme Court reversed the part of the High Court's judgment concerning the partition of co-owned property and remanded the case back to the Hiroshima High Court for further deliberation[cite: 1]. The High Court was tasked with re-examining the matter, specifically including an assessment of Y's ability to pay the compensation.

Dissecting "Comprehensive Compensation in Value"

The methods for partitioning co-owned property in Japan generally include:

- Genbutsu bunkatsu (Physical Division): The property itself is physically divided among the co-owners according to their share ratios. This is the primary method envisaged by the Civil Code if feasible.

- Daikin bunkatsu (Division of Proceeds): If physical division is impossible or would significantly reduce the property's value, the property is sold (typically by auction), and the monetary proceeds are distributed among the co-owners.

- Kakaku baishō (Compensation in Value): This involves one or more co-owners taking more than their share of the property (or the entire property) and compensating the other co-owners monetarily.

- Partial Compensation: This often occurs as an adjunct to physical division. If a precise physical division according to shares is difficult, one co-owner might receive a slightly larger or more valuable portion and pay a balancing amount to others. The Supreme Court's Grand Bench ruling of April 22, 1987, affirmed this as a permissible aspect of physical division[cite: 1].

- Comprehensive Compensation (zenmenteki kakaku baishō): This is the method at the heart of the 1996 Supreme Court decision. Here, one or a subset of co-owners acquires sole ownership of the entire property, and the remaining co-owners receive only monetary compensation for their shares; they do not retain any part of the physical property[cite: 2].

Before the 1996 ruling, there was considerable academic debate about whether comprehensive compensation was permissible in a court-ordered partition, given that the pre-2021 Civil Code Art. 258 did not explicitly list it[cite: 2]. Some scholars argued against it, emphasizing the statutory text[cite: 2]. The Supreme Court's decision to allow it, based on the "non-contentious" nature of partition suits and the need for judicial discretion, was therefore a significant jurisprudential step[cite: 2]. However, some commentators expressed skepticism about whether the non-contentious nature alone could justify creating a partition method not explicitly provided by statute[cite: 2].

Key Criteria for Comprehensive Compensation Post-1996

The 1996 Supreme Court judgment established a robust framework for assessing when comprehensive compensation is appropriate. The "special circumstances" test involves careful consideration of:

A. Reasonableness of Acquisition by One Co-owner:

This requires examining factors such as:

- Nature and configuration of the property: As in this case, physical indivisibility is a strong factor[cite: 2].

- Origin of the co-ownership: If the property was, for example, inherited, this might align with practices in estate division where compensation is common[cite: 2]. (In the reviewed case, the property was jointly repurchased by family members).

- Share ratios: If the co-owner wishing to acquire the property already holds a substantial share, this might be a supporting factor[cite: 2].

- Current use and necessity: The fact that Y was living on the Property and using it for her livelihood was a key consideration for the High Court, and not deemed unreasonable by the Supreme Court in principle[cite: 1, 2].

- Co-owners' wishes and their reasonableness: The desires of all parties are relevant. If the party seeking comprehensive compensation wishes to acquire, while others desire an auction (as here), the court weighs these preferences[cite: 2]. If other co-owners strongly prefer physical division (and it's feasible), ordering comprehensive compensation might require more caution[cite: 2].

B. Substantial Fairness Among Co-owners:

This is the bedrock of the method and hinges on:

- Fair Valuation: The property and, consequently, the shares of the exiting co-owners must be appraised accurately and fairly. The compensation should reflect the true market value to prevent unjust enrichment or loss[cite: 1, 2].

- Acquirer's Ability to Pay: This was the critical point of failure in the High Court's judgment in this case[cite: 1]. The Supreme Court made it unequivocally clear that the co-owner acquiring the property must have the proven financial capacity to pay the compensation owed[cite: 1, 2]. Without this, the exiting co-owners risk trading their real property interest for an uncertain or uncollectible monetary claim, which would be patently unfair[cite: 2]. This judgment, and another one issued by the Supreme Court on the same day, underscored the importance of this requirement by overturning lower court decisions that had neglected to confirm payment ability[cite: 2].

- Ensuring Payment: Related to the ability to pay is the mechanism for ensuring payment. Legal discussions, including supplementary opinions in other Supreme Court cases, have explored measures like ordering the transfer of share registration to be performed simultaneously with the payment of compensation (a concept akin to "cash on delivery")[cite: 2]. The perceived effectiveness of such enforcement measures could, in turn, influence the court's assessment of whether the "ability to pay" criterion is truly satisfied[cite: 2].

The Legacy of the 1996 Judgment and the 2021 Civil Code Amendments

The landscape of co-ownership partition in Japan underwent a significant legislative update with the 2021 revisions to the Civil Code.

- Codification of Comprehensive Compensation: The amended Civil Code now explicitly includes, in Article 258, Paragraph 2, Item 2, the option for a court to order a partition where one co-owner acquires the property and compensates others[cite: 3]. This legislative change means that the part of the 1996 Supreme Court judgment that established the permissibility of comprehensive compensation has, in a sense, been superseded by statute; its unique historical importance for that specific point has diminished[cite: 3].

- Continued Relevance of the "Special Circumstances" Test: Crucially, while the 2021 amendments codified the method, they did not codify the detailed requirements or "special circumstances" that the 1996 Supreme Court judgment laid out[cite: 3]. According to commentary on the legislative process, this omission was deliberate, partly to avoid creating a rigid statutory hierarchy that might imply physical division must always be preferred over compensation-based methods if the conditions for the latter are met[cite: 3].

Therefore, the analytical framework established by the Heisei 8 (1996) Supreme Court judgment—the comprehensive consideration of factors determining reasonableness and the strict requirements for ensuring financial fairness—is expected to remain fundamentally relevant for courts applying the newly codified Article 258(2)(ii)[cite: 3].

Future judicial practice will likely continue to refine the application of these criteria. For instance, the explicit wishes of the co-owners (now a more prominent consideration in the amended law's structure) might influence the weighting of different factors[cite: 3]. Furthermore, the Civil Code amendments also introduced clearer provisions regarding court orders for payment and other ancillary measures (e.g., Article 258, Paragraph 4, concerning orders to deliver money), which could affect how courts assess and ensure the "ability to pay"[cite: 3].

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of October 31, 1996, stands as a vital precedent in Japanese property law. It judiciously balanced the need for flexibility in resolving often intractable co-ownership disputes with the paramount importance of protecting the substantive and financial rights of all co-owners. By formally recognizing comprehensive compensation in value while simultaneously imposing strict conditions—most notably, the acquirer's proven ability to pay—the Court provided a pathway for practical solutions in cases where physical division is unsuitable. Even with the 2021 Civil Code amendments that now explicitly list this partition method, the detailed conditions and the spirit of fairness articulated in this 1996 judgment continue to guide Japanese courts in ensuring that the dissolution of co-ownership is both equitable and just.