Fair Market Value, Foul Play: How Japan's High Court Redefined Bribery

What is a bribe? The classic image is a bag of cash or an extravagant gift given to a public official in exchange for a favor. But what if the transaction is more subtle? Can a seemingly legitimate business deal, conducted at a fair market price, still constitute a criminal bribe? What if the "benefit" is not an inflated price or a secret commission, but the very opportunity to make the deal itself—an opportunity provided at a crucial moment as a reward for an official's actions?

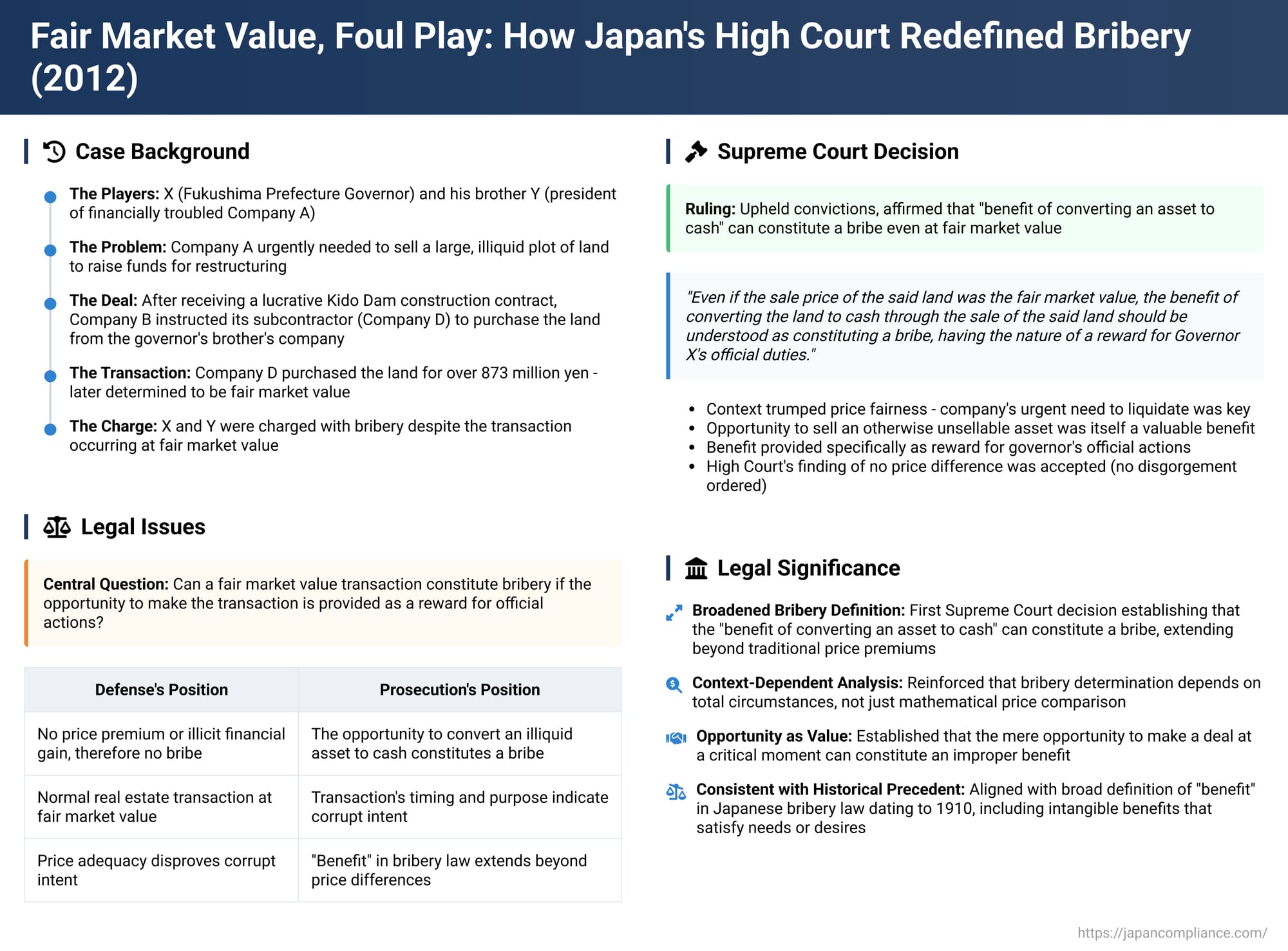

This sophisticated question was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on October 15, 2012. In a major political corruption case involving a prefectural governor, the Court found that the "benefit of converting an asset to cash" can be a bribe, even when no extra money changes hands. The ruling provides a powerful insight into the broad and context-dependent nature of bribery law in Japan.

The Facts: The Governor, the Brother, and the Unsellable Land

The case centered on X, the powerful Governor of Fukushima Prefecture, and his younger brother, Y.

- The Players:

- As governor, X held authority over major public works contracts in the prefecture.

- His brother, Y, was the president of a company, A, that was in financial distress.

- The Problem: Company A urgently needed to sell a large, illiquid plot of land to raise funds for corporate restructuring. However, it was having significant difficulty finding a buyer.

- The Quid Pro Quo:

- The Fukushima prefectural government awarded a lucrative contract for the construction of the Kido Dam to a joint venture led by a major construction firm, Company B.

- As a gesture of gratitude for Governor X's "favorable treatment" in the awarding of this contract, C, the vice chairman of Company B, instructed a subcontractor, Company D, to purchase the unsellable land from the governor's brother's company.

- The Transaction:

- Knowing that the purchase was being made as a "thank you" for the dam contract, Governor X and his brother Y conspired. Y formally asked E, the vice president of the subcontractor Company D, to buy the land.

- Company D agreed and purchased the land from Company A for over 873 million yen. This amount was later determined to be the fair market value for the property. The funds were wired directly to Company A's bank account.

The Legal Question: Where is the Bribe?

The defense's argument was simple: this was a normal real estate transaction conducted at a fair market price. Since there was no price difference between the sale price and the market value, there was no illicit financial gain, and therefore, no bribe.

The lower courts wrestled with this question.

- The District Court convicted the brothers, finding two forms of bribe: (1) the benefit of converting the land to cash, and (2) an alleged price difference of over 73 million yen, which it ordered to be disgorged.

- The High Court, on appeal, also convicted them but on narrower grounds. It found the evidence for a price difference to be unclear and refused to recognize it as a bribe. However, it held that the intangible "benefit of converting the land to cash" (kankin no rieki) was, in itself, a sufficient bribe to sustain the conviction. Since this benefit could not be valued in monetary terms, it ordered no disgorgement.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Opportunity as a Bribe

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions, cementing the High Court's reasoning into a major legal precedent. The Court's decision was unequivocal:

"Under these factual circumstances, even if the sale price of the said land was the fair market value, the benefit of converting the land to cash through the sale of the said land should be understood as constituting a bribe, having the nature of a reward for Governor X's official duties."

The Court's logic was that the context was everything. The brother's company was in a bind, desperate to sell an illiquid asset but unable to do so. The opportunity to immediately liquidate this asset and secure hundreds of millions of yen in cash—an opportunity provided specifically as a reward for the governor's official actions—was an immense benefit in its own right, entirely separate from the fairness of the price.

Analysis: The Broad Scope of "Benefit" in Japanese Bribery Law

This 2012 decision, while the first of its kind from the Supreme Court, is consistent with a long and established tradition in Japanese law of defining a "bribe" extremely broadly.

- The Classic Definition: Since a 1910 precedent, a bribe has been understood as "any benefit, tangible or intangible, sufficient to satisfy a person's needs or desires." This has been held to include not only money and goods but also things like entertainment, lavish meals, and even sexual favors.

- The "Godsend" Principle: The key question is whether a given benefit could corrupt the "fairness of a public official's duties and the public's trust in it." In this case, the opportunity to sell the unsellable land at a moment of desperate need was a "godsend" (watari ni fune), a timely benefit of immense value to the governor's brother's company.

- Parallels with Other Landmark Cases: This principle is not without precedent in other complex financial cases.

- The IPO Stock Case: In a famous 1988 case, the Supreme Court held that the opportunity for an official to purchase pre-IPO stock at the public offering price was a bribe. The key factors were the near certainty that the stock price would rise upon listing and the extreme difficulty for ordinary people to obtain such shares.The "difficulty of selling" the land in the present case is seen as analogous to the "difficulty of obtaining" the shares in the stock case.

- The "Benefit of Financing": It has long been held that the mere act of providing a loan to an official can be a bribe, separate from the loan principal itself. The benefit is the access to liquidity. The land sale in this case served the exact same function: it converted a highly illiquid asset into extremely liquid cash for the company's restructuring needs.

- The Disgorgement Problem: The case also highlights a unique legal consequence. Because the "benefit of converting an asset to cash" is an intangible opportunity, its precise monetary value cannot be calculated. As a result, while the High Court affirmed it was a bribe, it could not order a specific amount to be disgorged under the mandatory disgorgement provisions of the Penal Code. This contrasts with the IPO stock case, where the value of the bribe could be calculated as the difference between the offering price and the post-listing market price.

Conclusion

The 2012 ruling on the Fukushima governor's case is a powerful clarification of the breadth of Japanese bribery law. It is the first Supreme Court decision to firmly establish that the "benefit of converting an asset to cash" can be a criminal bribe, even if the underlying transaction occurs at a perfectly fair market price. The decision serves as a critical reminder that, in the eyes of the law, context is king. A transaction that appears legitimate on its face can be deemed criminally corrupt if its timing and opportunity are provided as a reward for an official's duties and confer a significant, tailored benefit on the official or their close associates. This case sends a clear message to all who do business with the government in Japan: a bribe is not just about the price; it can also be about the opportunity.