Fair Dealings in Japan: Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position and the "Oshigami" Case

TL;DR

- Japan’s Antimonopoly Act polices unfair B2B conduct via the Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (ASBP) rule.

- In the 2023 Osaka High Court “Oshigami” case, a distributor failed to prove a publisher’s refusal to cut excess newspaper copies was unjust—the court accepted the publisher’s business rationale.

- The ruling highlights three compliance pillars: assess true bargaining leverage, document negotiations, and justify refusals with rational grounds.

Table of Contents

- The Legal Framework: Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position

- Case Study: The "Oshigami" Dispute (Osaka High Court, April 14, 2023)

- Analysis and Implications

- Conclusion

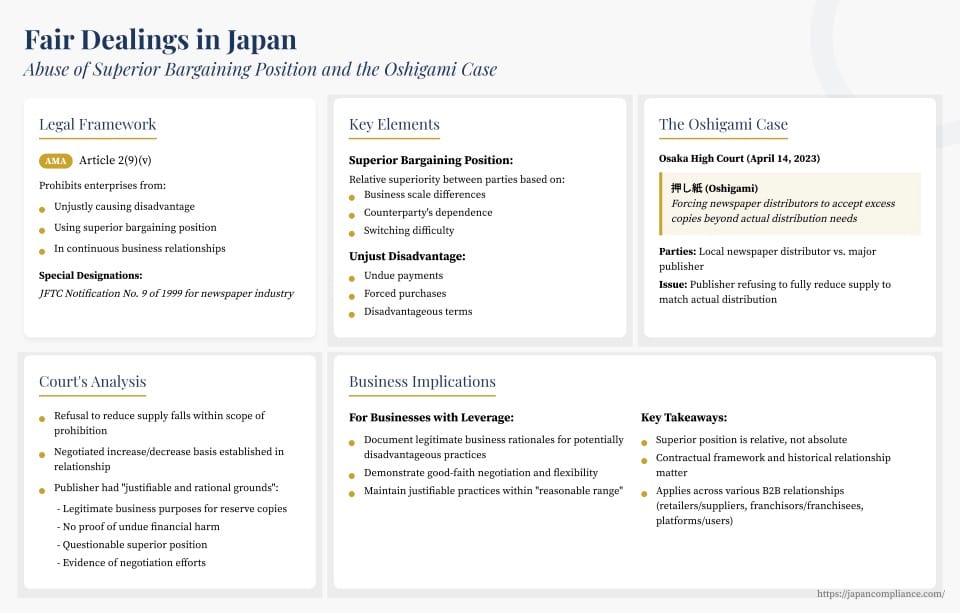

When engaging in business-to-business transactions in Japan, companies need to be aware of a unique aspect of Japanese competition law: the prohibition against "Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position" (優越的地位の濫用, Yūetsuteki Chii no Ranyō). Found in Article 2, Paragraph 9, Item 5 of Japan's Act on Prohibition of Private Monopolization and Maintenance of Fair Trade (the Antimonopoly Act or AMA), this provision targets conduct that unfairly disadvantages business partners where a significant power imbalance exists, even if the conduct doesn't rise to the level of monopolization or cartel activity. A recent court decision concerning the newspaper distribution industry and a practice known as oshigami provides a valuable illustration of how these principles are applied.

The Legal Framework: Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position

Article 2(9)(v) of the AMA generally prohibits an enterprise from unjustly causing disadvantage to another party with whom it has a continuous business relationship, by making use of its superior bargaining position relative to that party. Key elements typically include:

- Superior Bargaining Position: The alleged abuser must hold a position of relative superiority over the counterparty. This doesn't necessarily require market dominance; factors like differences in business scale, the counterparty's degree of dependence on the transaction, the difficulty of switching partners, and the supplier's brand power are considered.

- Unjust Disadvantage: The conduct must cause a disadvantage to the counterparty that is deemed unjust in light of normal business practices. Examples include demanding undue payments, forcing purchases of unwanted goods, imposing disadvantageous terms, or refusing to deal unfairly.

- Making Use of the Position: The disadvantage must result from the enterprise leveraging its superior position.

For certain industries, the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) has issued "Special Designations" (Tokutei Fukōsei na Torihiki Hōhō) that outline specific prohibited practices. The newspaper industry is one such sector, governed by JFTC Notification No. 9 of 1999.

Case Study: The "Oshigami" Dispute (Osaka High Court, April 14, 2023)

This case (Ōsaka Kōtō Saibansho, April 14, 2023) involved a newspaper distributor and a major newspaper publisher.

Background:

The plaintiff, a local newspaper distributor (Distributor X), primarily handled distribution for a major national newspaper but also had a long-standing contract to distribute another national newspaper published by the defendant (Publisher Y). From the beginning of their relationship, Distributor X requested Publisher Y supply only the number of copies needed for actual distribution (jitsuhai busū), with no "reserve copies" (yobishi). Publisher Y, however, insisted on supplying a certain number of reserve copies beyond the actual distribution needs, and Distributor X paid for the full quantity supplied.

A later contract obligated Distributor X to "endeavor to maintain and expand sales." Distributor X regularly submitted reports to Publisher Y showing the actual number of copies distributed (jitsuhai busū). Between 2016 and 2019 (the "Claim Period"), Distributor X made at least 20 requests to reduce (genshi) the number of supplied copies to better match actual distribution. Publisher Y offered financial subsidies for part of this period and negotiated some reductions, but never agreed to reduce the supply down to the actual distribution level requested by X.

Distributor X sued Publisher Y for damages, alleging that supplying copies exceeding the reported jitsuhai busū constituted oshigami (押し紙 – literally "pushed paper," referring to forced acceptance of excess copies). X argued this violated Item 3(i) of the Special Designation for the Newspaper Industry, which prohibits supplying more copies than ordered, including doing so by refusing a distributor's request for a reduction (genshi no mōshide ni ōjinai hōhō ni yoru baai o fukumu), unless there are "justifiable and rational grounds" (seitō katsu gōriteki na riyū). The District Court had dismissed the claim.

The High Court's Decision:

The Osaka High Court affirmed the dismissal, but its reasoning differed significantly regarding the application of the Special Designation.

- What Was "Ordered"? The court rejected Distributor X's argument that the jitsuhai busū reports constituted the "ordered quantity." Examining the history of the relationship and the contract terms, the court found that the supply arrangement operated on a "negotiated increase/decrease basis" (kyōgi zōgen hōshiki). This meant the existing supply level continued unless both parties agreed to a change. It was not a "free increase/decrease basis" (jiyū zōgen hōshiki) where X could unilaterally dictate the quantity via an order. Therefore, simply supplying more than the jitsuhai busū did not automatically mean Publisher Y supplied more than the "ordered" quantity.

- "Refusal to Reduce" Triggered Scrutiny: Crucially, however, the High Court found that Publisher Y's failure to fully accept Distributor X's repeated reduction requests did fall within the scope of the Special Designation's prohibition, specifically the part concerning "refusing...a request for a reduction." This meant Publisher Y's conduct required justification.

- Justifiable and Rational Grounds Found: The court then assessed whether Publisher Y had "justifiable and rational grounds" for not meeting the full reduction requests. It concluded that such grounds existed, based on a comprehensive review of the circumstances:

- Business Rationale for Reserve Copies: Supplying reserve copies serves legitimate purposes, such as incentivizing distributors' sales efforts and simplifying the publisher's monitoring of those efforts. Distributor X was aware of and had implicitly accepted the practice of receiving reserve copies since the beginning of the relationship. Therefore, not obtaining the full requested reduction did not constitute an "unforeseeable disadvantage" (arakajime keisan dekinai furieki).

- No Proof of Undue Harm: Distributor X failed to provide sufficient evidence that the level of reserve copies imposed caused it substantial financial harm, such as forcing it to operate at a loss (gyakuzaya) on the publisher's newspapers. The court considered whether the burden exceeded a reasonable range.

- Lack of Proven Superior Position: The court questioned whether Publisher Y actually held a "superior bargaining position" over Distributor X in this specific relationship. Distributor X's main business involved distributing a different major newspaper. Its dependence on Publisher Y's newspaper was not clearly established. The court inferred that Distributor X likely could have stopped distributing Publisher Y's paper without facing critical business disruption, which limited Publisher Y's leverage.

- Negotiation Efforts: Publisher Y did not simply ignore the reduction requests. It engaged in negotiations, agreed to partial reductions over time, and provided financial subsidies as a compensatory measure.

- Conclusion: Considering these factors together, the High Court determined that Publisher Y's actions were supported by justifiable and rational grounds. Therefore, the conduct did not constitute an unfair trade practice under the Special Designation, nor did it amount to an unlawful tort.

Analysis and Implications

This case offers valuable insights into the application of Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position principles in Japan:

- Superior Position is Relative: The ruling underscores that "superior bargaining position" is assessed relatively between the parties involved, considering factors like dependence, switching costs, and business scale. Market dominance is not required. Here, the distributor's perceived ability to walk away weakened the claim of the publisher's superiority.

- Contractual Framework Matters: How the transaction is structured and understood (e.g., order-based vs. negotiation-based quantity adjustments) is critical. Courts will look at the contract and the parties' course of dealing.

- Partial Refusals Can Trigger Scrutiny: The finding that not fully granting a reduction request can fall under the specific prohibition (in the Special Designation) is noteworthy. It places the onus on the dominant party to justify its partial refusal.

- "Justifiable Grounds" are Key: This is often the central battleground. Legitimate business reasons (like incentivizing sales efforts), the absence of proven disproportionate harm to the counterparty, and evidence of good-faith negotiation can serve as strong defenses. The assessment is holistic and fact-dependent.

- Broader Relevance: Although decided under industry-specific rules, the core principles analyzed—relative power, disadvantage, justification—mirror those applied under the general Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position clause (AMA Art. 2(9)(v)). These principles are relevant across various B2B relationships, including large retailers vs. suppliers, franchisors vs. franchisees, and digital platforms vs. business users. The JFTC's general guidelines on this topic provide further context and examples. The court's focus on "unforeseeable disadvantage" and whether burdens exceed a "reasonable range" aligns with the spirit of these guidelines.

Conclusion

Japan's prohibition on Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position is a distinct and significant feature of its competition law landscape, focusing on fairness in commercial dealings beyond traditional antitrust concerns. The oshigami case illustrates that applying these rules, even industry-specific ones, involves a nuanced, fact-intensive analysis. Courts evaluate the relative power dynamics, the concrete impact of the challenged conduct, and crucially, the presence of legitimate business justifications. Companies holding significant leverage in their dealings with Japanese business partners should remain mindful of these principles to ensure their practices are fair and justifiable under the AMA.

- False IP Takedowns on Japanese E-Commerce Platforms: UCPA Liability & Risk-Control Guide

- Antitrust Enforcement in Japan’s Energy Sector: JFTC Lessons from Cartel & Collusion Cases

- Franchising in Japan: Antimonopoly Act Risks, ASBP Case Study & Compliance Steps for US Brands

- JFTC Guidelines Concerning Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (English)