Eyes on the Horizon: Japan's Supreme Court on Assigning Claims That Don't Yet Exist

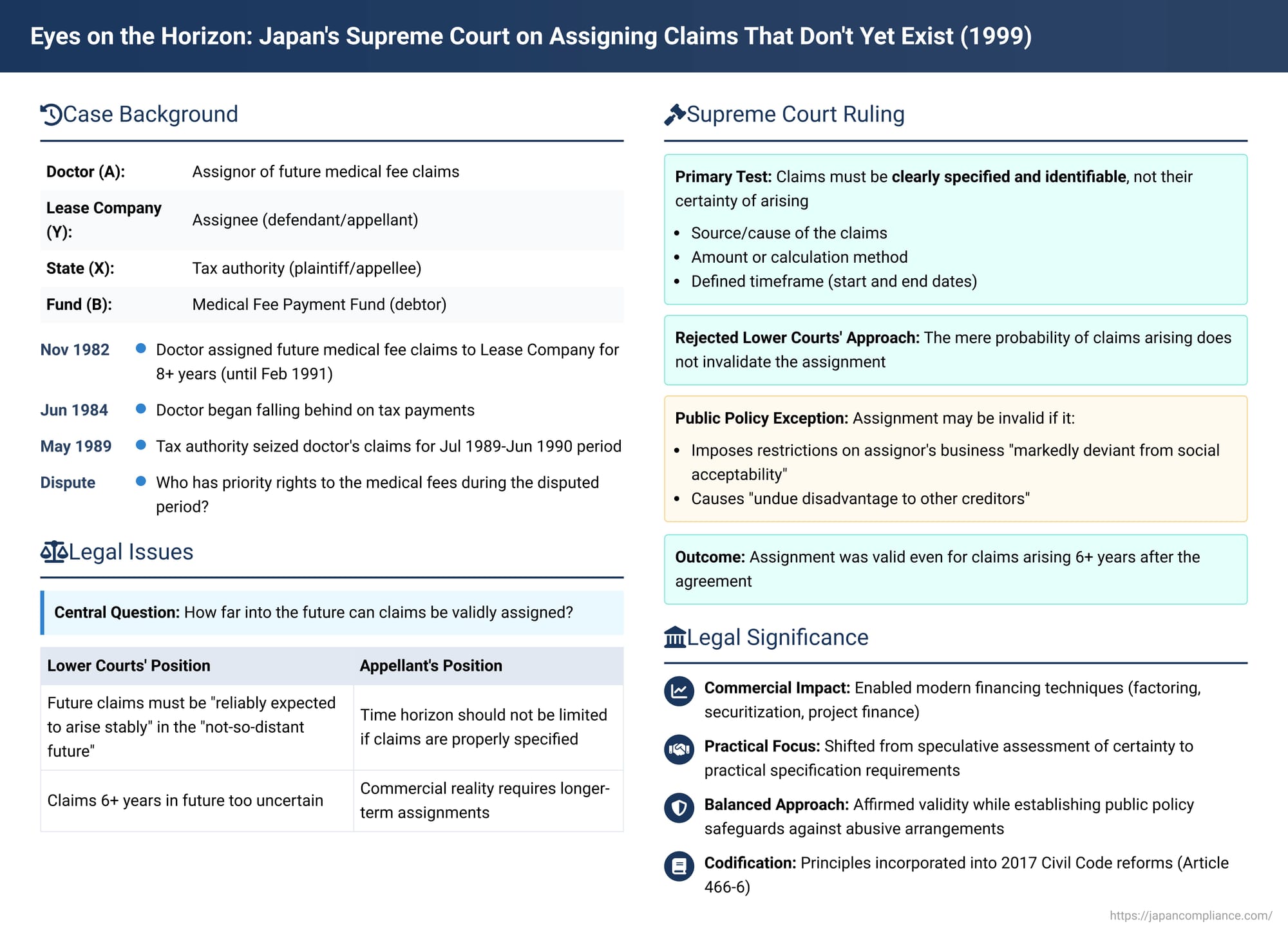

In the world of finance and commerce, the ability to use future income streams as a basis for current transactions is vital. But how far into the future can one validly assign a claim that hasn't even materialized yet? A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision on January 29, 1999 (Heisei 9 (O) No. 219), provided crucial clarity on the validity of assigning such "future claims" (shōrai saiken), a judgment whose principles have since been embedded in Japan's Civil Code.

The Concept of Assigning Future Claims

Future claims are rights to payment or performance that are expected to arise from contractual relationships or other causes but do not yet exist at the time of the assignment agreement. Examples include future rent from a property, future royalties from intellectual property, or, as in this case, future fees for services yet to be rendered. Businesses often seek to assign these anticipated claims to secure loans, obtain financing (like factoring), or otherwise manage their cash flow. Before this 1999 ruling, there was considerable uncertainty in Japanese law about the extent to which, and under what conditions, such assignments of yet-to-be-born claims were legally effective, especially if they stretched many years into the future.

Facts of the 1999 Case: A Doctor's Future Earnings Assigned, Then Seized by Tax Authorities

The case involved a conflict over a doctor's future medical service fees:

- The Parties:

- A: A doctor operating a clinic (the assignor).

- Y: A lease company (the assignee, to whom Dr. A owed money).

- B: The Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund (the "Fund"), which would pay Dr. A for services rendered to patients covered by social insurance.

- X: The State (specifically, the tax authority), a competing claimant.

- The Assignment of Future Claims: On November 16, 1982, Dr. A entered into a contract with Y (the lease company). To secure A's existing debts to Y, A agreed to assign to Y a specified portion of the medical service fee claims that A would earn from the Fund (B) over a long future period – specifically, from December 1, 1982, to February 28, 1991 (a period of over eight years). On November 24, 1982, Dr. A formally notified the Fund (B) of this assignment using a document with a certified date (kakutei hizuke), which is a method for perfecting an assignment against the third-party debtor and other third parties.

- Tax Delinquency and Seizure: Years later, from June 1984, Dr. A became delinquent in paying national taxes. On May 25, 1989, X (the State) took action to seize, as part of a tax delinquency procedure, Dr. A's medical fee claims receivable from the Fund (B) for the period covering July 1, 1989, to June 30, 1990 (the "Disputed Claims Period"). This seizure notice was served on the Fund on the same day. This Disputed Claims Period fell within the timeframe of the future claims previously assigned by A to Y.

- The Dispute: The Fund, faced with competing claims from Y (as assignee) and X (as the seizing tax authority) for the medical fees generated during the Disputed Claims Period, deposited the relevant amount (approximately 5.2 million yen) with the authorities. X then sued Y, arguing that the portion of the 1982 assignment contract relating to such distant future claims (specifically, those maturing more than a year after the assignment began, which included the Disputed Claims Period occurring roughly 6.5 years later) was invalid. If the assignment to Y was invalid for this period, then Dr. A would still be the rightful creditor, and X's tax seizure against A would take precedence. The lower courts (first and second instance) agreed with X, holding that the assignment of claims so far into the future, where their stable generation could not be "reliably expected," was invalid. Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: Future Claim Assignments Generally Valid

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions and ruled in favor of Y (the original assignee). The Court laid down several key principles regarding the assignment of future claims:

- Certainty of Claim Arising is NOT the Primary Test for Validity:

The Court explicitly rejected the lower courts' premise that an assignment of future claims is only valid if the claims are "reliably expected to arise stably" in the "not-so-distant future." [cite: 1] It stated that in such assignment contracts, the contracting parties (assignor and assignee) are presumed to have considered the circumstances underlying the potential generation of the future claims and the likelihood of their actual occurrence. [cite: 1] If the claims do not arise as anticipated, any resulting loss to the assignee is typically a matter to be resolved based on the assignor's contractual liability (e.g., for breach of warranty, if such a warranty was part of the assignment agreement). [cite: 1] Therefore, a low probability of the claims actually arising, as assessed at the time of the assignment contract, does not automatically invalidate the assignment itself. [cite: 1] - Sufficient Specification of the Assigned Claims IS Essential:

What is crucial for the validity of a future claim assignment is that the claims being assigned are clearly specified and identifiable. [cite: 1] The Court indicated that this specification should generally include details such as the cause from which the claims will arise (e.g., ongoing medical services), the amount to be assigned (or a method to determine it), and, if the assignment covers multiple claims over a period, the start and end dates of that period must be clearly defined through appropriate means. [cite: 1] - Limitations – Public Policy (Public Order and Morals):

While generally affirming the validity of future claim assignments, the Supreme Court also established an important safeguard: such an assignment can be deemed wholly or partially invalid if it violates public policy (public order and morals - kōjo ryōzoku). [cite: 1] The Court provided examples of situations where this might occur:- If the assignment imposes restrictions on the assignor's ongoing business activities that are "markedly deviant from what is considered socially acceptable" (e.g., an assignment that ties up virtually all of the assignor's future income for an excessively long duration, crippling their ability to operate or seek other financing). [cite: 1]

- If the assignment causes "undue disadvantage to other creditors" of the assignor (e.g., if one assignee effectively monopolizes all future revenue streams, unfairly harming the prospects of other legitimate creditors). [cite: 1]

- Clarification of Prior Case Law:

The Court also clarified that a widely cited 1978 Supreme Court decision, which had affirmed the validity of a one-year assignment of future medical fees, should not be interpreted as setting a general time limit or a restrictive standard for all future claim assignments. That earlier decision was merely a judgment based on its own specific facts. [cite: 1] - Outcome of the Case:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found that the 1982 assignment contract between Dr. A and Y clearly specified the claims to be assigned (including the period and amounts). It found no "special circumstances" in this case that would render the assignment of claims during the Disputed Claims Period contrary to public policy. The Court noted that it is common for professionals like doctors to incur significant debt when establishing their practices and that they may not always have tangible assets like real estate to offer as security. Assigning future professional fees can be a reasonable method for them to obtain necessary financing, and for lenders to secure such loans based on the doctor's future earning potential. Such an arrangement does not inherently imply that the doctor was already in a poor financial state or that it would inevitably lead to financial ruin. As there was no evidence of abusive terms or undue harm to other creditors that met the public policy exception, the assignment to Y was held valid even for the claims arising years later. Consequently, Y's rights as the assignee took priority over X's subsequent tax seizure.

Significance of the Ruling and Impact on Business Financing

This 1999 Supreme Court decision was a watershed moment for the law governing future claim assignments in Japan:

- Increased Legal Predictability: It provided much-needed clarity and generally affirmed the validity of assigning claims that would arise in the future, a practice crucial for various modern financing techniques such as factoring, securitization of future revenues, and project finance.

- Focus on Specification, Not Speculation: The ruling correctly shifted the legal emphasis from speculative assessments about the certainty of a future claim's emergence to the practical requirement of ensuring that the description and scope of the assigned claims are clearly defined in the contract.

- The Public Policy Backstop: While broadly endorsing the assignability of future claims, the introduction of the public policy exception served as an important safeguard against potentially abusive or overly burdensome assignment arrangements that could unduly harm the assignor or other creditors.

Codification and Legacy in the 2017 Civil Code Reforms

The principles established by this 1999 Supreme Court judgment were influential and have largely been incorporated into the Japanese Civil Code through the major reforms to the law of obligations, which came into effect in 2017:

- Explicit Recognition of Future Claim Assignments: The reformed Civil Code now explicitly states in Article 466-6, Paragraph 1: "An assignment of a claim does not require that the claim actually exists at the time of the juridical act effecting the assignment." [cite: 1] This directly reflects the Supreme Court's stance.

- Perfection of Future Claim Assignments: Subsequent Supreme Court case law (e.g., a ruling on November 22, 2001) confirmed that the perfection requirements for future claim assignments (such as notice to the third-party debtor with a certified date, or the debtor's consent with a certified date) can be fulfilled in the same manner as for existing claims. [cite: 1] This understanding is also reflected in the reformed Civil Code's provisions on perfecting assignments (e.g., new Article 467, Paragraph 1).

- Ongoing Relevance of Public Policy: The possibility that an assignment of future claims could be invalidated for violating public order and morals remains relevant even under the reformed code. [cite: 1]

Remaining Questions

Even with these clarifications, some theoretical aspects, such as the precise legal nature of the assignee's acquisition of the claim at the moment it arises (e.g., whether it's a direct acquisition or a derivative one from the assignor), continue to be subjects of academic discussion in Japan. [cite: 1]

Conclusion

The 1999 Supreme Court judgment on the assignment of future claims was a pivotal decision that significantly liberalized and provided a clear framework for this important commercial practice in Japan. By prioritizing the clear specification of assigned claims over the speculative certainty of their future emergence, and by establishing a public policy safety net against abusive arrangements, the Court struck a pragmatic balance. This approach supports modern financing needs while safeguarding against potential overreach, and its core principles are now firmly established in Japan's reformed Civil Code.