Expanding Claims in Japanese Security Auctions: Supreme Court Allows Correction for Errors in Distribution Objections

When a creditor enforces a security interest, such as a revolving mortgage (ne-teitōken), through a real property auction in Japan, they must specify their claim in the initial application. A critical question arises if the creditor initially states only a portion of their total secured debt—for example, claiming only the principal amount and omitting accrued interest or damages. Can the creditor later, particularly during the distribution of the auction proceeds, seek to expand their claim to include these omitted amounts, especially if the total still falls within the maximum secured limit of their mortgage? A 2003 Supreme Court of Japan decision addressed this complex issue, offering a nuanced solution that balances procedural stability with the substantive rights of secured creditors.

Background of the Dispute

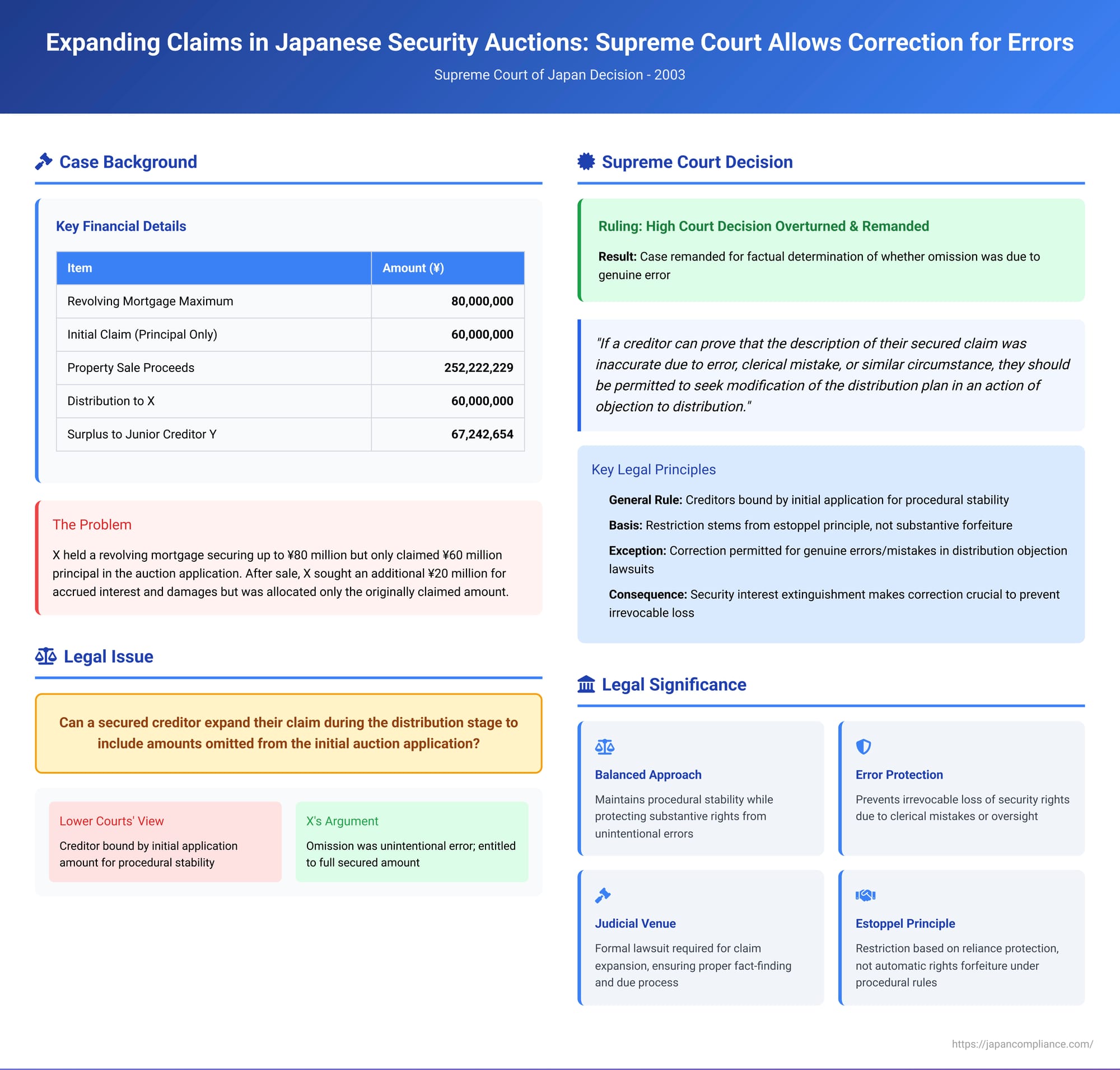

The plaintiff, X, held a revolving mortgage (ne-teitōken) with a maximum secured amount (極度額 - kyokudogaku) of 80 million yen. This mortgage was established over several real properties owned by guarantors (B and others) to secure debts owed to X by the principal debtor, Company A. X's revolving mortgage was duly registered but ranked junior to prior mortgages held by C Bank and D Company.

X initiated a compulsory auction to enforce this revolving mortgage against the guarantors' properties. In the formal auction application submitted to the E District Court, X described its security interest as the 80 million yen revolving mortgage. However, under the section for "Secured Claim and Claimed Amount" (被担保債権及び請求債権 - hi-tanpo saiken oyobi seikyū saiken), X specified "Principal: 60 million yen (loan made on November 15, 1994, based on a loan for consumption agreement)." The application made no explicit mention of accrued interest or damages that might also be covered by the revolving mortgage.

The auction proceeded, and the properties were successfully sold for a total of 252,222,229 yen. After the purchase price was paid, the court moved to the distribution stage. Following the satisfaction of the claims of creditors senior to X, the court prepared a distribution plan. In this plan, X was allocated 60 million yen—the principal amount stated in its auction application. The remaining surplus, amounting to 67,242,654 yen, was allocated to Y, a creditor whose rights were junior to X's revolving mortgage.

X objected to this distribution. X argued that its revolving mortgage secured not only the 60 million yen principal but also accrued interest and damages. X contended that it was entitled to an additional 20 million yen from the sale proceeds (for this interest and damages, keeping the total claim within the 80 million yen maximum secured amount of the revolving mortgage) before any distribution was made to the junior creditor Y. To assert this, X filed an "action of objection to distribution" (配当異議の訴え - haitō igi no uttae), a formal lawsuit to challenge the proposed distribution plan.

However, both the court of first instance and the High Court dismissed X's claim. They essentially ruled that X was bound by the 60 million yen amount stated in its initial auction application and could not expand it at the distribution stage. X then sought and was granted permission to appeal to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court acknowledged the reasons typically given for restricting such expansions but found them not to be absolute, especially in cases of error.

The lower courts had reasoned that the Civil Execution Rules (specifically Article 170, items 2 and 4, which require the auction application to state the secured claim and claimed amount, and if only part is being enforced, that fact and its scope) are intended to ensure procedural stability. The initially claimed amount is crucial for various determinations during the auction, such as avoiding an excessive sale of property or deciding if there's a sufficient surplus over prior claims for the auction to even proceed (the "no-surplus, no-auction" rule). Allowing the applying creditor to arbitrarily expand their claim later, especially at the distribution stage, could undermine this stability and potentially necessitate the cancellation of the entire auction. Thus, the general stance was that an applying creditor is bound by their initial statement, with the possibility of filing a separate, new auction application for any remaining part of their claim if done before the distribution demand deadline in the first auction.

The Supreme Court, however, offered a more nuanced perspective:

- Purpose of the Civil Execution Rules (Art. 170): The Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts that the primary purpose of Article 170 of the Civil Execution Rules (requiring a clear statement of the claimed amount in the auction application) is indeed to ensure the stable and orderly progress of the auction procedure. It also concurred that, as a general principle, a creditor who initiates an auction by claiming only a part of their secured debt can be restricted from expanding that claim within that same ongoing auction procedure.

- Basis of Restriction – Estoppel, Not Substantive Forfeiture: Crucially, the Supreme Court clarified that this restriction on expanding the claim during the auction procedure stems from the principle of estoppel (禁反言 - kinpangen) in relation to other parties involved in the auction (e.g., junior creditors, the debtor) who may have relied on the applying creditor's initial, limited claim. The Civil Execution Rules themselves (Article 170) do not create a substantive law effect whereby the creditor automatically forfeits their right to preferential payment for the unclaimed portion of their secured debt simply by filing a partial claim. The rules are procedural, aimed at orderly execution, not at extinguishing underlying substantive rights beyond the scope of the specific execution initiated.

- The Problem of Irrevocable Loss in Security Interest Auctions: The Court highlighted a critical difference in the consequences of partial claims in security interest auctions versus general compulsory auctions. In an auction to enforce a security interest like a mortgage, the sale of the collateral extinguishes the security interest itself (as per Article 59, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Execution Act). This means the secured creditor loses their right to preferential payment from that specific collateral for any portion of the secured debt that was not claimed and satisfied from the proceeds of that particular sale. This loss is not just for that auction but is a permanent loss of the security over that asset for the unclaimed debt portion.

Given this potentially irrevocable loss, the Supreme Court reasoned that if a creditor, due to a genuine error, clerical mistake, or similar oversight (錯誤、誤記等 - sakugo, goki tō), failed to include parts of their legitimately secured claim in the initial auction application, despite having no actual intention to waive their rights to those amounts, then rigidly prohibiting them from ever asserting their true, full secured claim (up to the security's maximum limit) would be an unduly harsh consequence not automatically mandated by the principle of estoppel or the procedural intent of Rule 170. - Correction Permitted in an Action of Objection to Distribution: Based on this understanding, the Supreme Court concluded that in a formal lawsuit such as an "action of objection to distribution," if the applying secured creditor can prove that the description of the secured claim in their initial auction application was inaccurate due to an error, clerical mistake, or similar circumstance, and can also establish the true and full amount of their secured claim (within the limits of their security interest), they should be permitted to seek a modification of the proposed distribution plan to reflect the true state of their rights.

- Application to X's Case: In the present case, X had detailed the full principal amount of the underlying loan (60 million yen) that was part of its revolving mortgage's coverage but had made no mention in the "Claimed Amount" section of accrued interest or damages, which are also typically secured by a revolving mortgage up to its maximum amount (80 million yen). The Supreme Court found that this omission in the application did not, by itself, definitively indicate an intention by X to waive its right to preferential payment for any accrued interest and damages that were validly secured by the revolving mortgage.

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the lower courts had erred in dismissing X's claim solely based on the content of the initial auction application. They should have instead examined whether X's failure to explicitly claim interest and damages in the initial application was due to an error or mistake that would justify a correction in the distribution plan through the action of objection to distribution. The case was remanded to the High Court for this factual determination.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 2003 Supreme Court decision provided important clarification on a long-debated issue in Japanese security enforcement law, offering a pathway for secured creditors to correct initial understatements of their claims under specific circumstances.

- Background of the Debate: The PDF commentary explains that while creditors can choose to make partial claims, the consequences differ between general executions and security interest executions. In the latter, the security interest over the sold property is extinguished, meaning any unclaimed part of the debt loses its secured status regarding that property. This creates a strong incentive for creditors to claim their full secured amount or seek ways to expand it if the property sells for a high price. However, allowing unfettered post-application expansion was seen as problematic for procedural stability, reliance interests of other parties, and potential abuse (e.g., to initially lower registration taxes).

- Evolution of Legal Interpretation: Before the current Civil Execution Act, case law and academic opinion were generally more permissive of claim expansion in security auctions. However, after the Act's enactment (with Rule 170 requiring specification of partial claims and Article 59(1) confirming extinguishment of the security interest), the prevailing view among courts and in practice shifted towards denying such expansions, with very limited exceptions for obvious clerical errors. This Supreme Court decision emerged against that backdrop.

- The Court's Nuanced Approach: The Supreme Court, in this case, affirmed the general principle that the initial claim amount is binding within the auction procedure itself for reasons of procedural stability and estoppel. However, it crucially differentiated between the auction procedure and a subsequent action of objection to distribution. It clarified that the procedural rule (Art. 170) does not cause a substantive forfeiture of the secured creditor's underlying priority rights for unclaimed amounts if the omission was unintentional.

- Estoppel as the Limiting Factor: By grounding the restriction on claim expansion in the principle of estoppel, the Court opened the door for exceptions when the elements of estoppel are not fully met—specifically, when the initial understatement was due to genuine error or mistake, rather than a deliberate choice upon which others reasonably relied to their detriment.

- The Action of Objection to Distribution as the Venue for Correction: The decision identifies the action of objection to distribution (a full judicial proceeding) as the appropriate venue for a creditor to prove such an error and establish the true extent of their secured claim, seeking a corrected distribution plan. This distinguishes it from attempts to expand the claim merely by submitting an amended calculation sheet during the administrative phases of the distribution within the execution court itself, which would generally still be disallowed. The requirements for proving such an error are likened by the commentary to the strict conditions for withdrawing a judicial admission (e.g., proving it was contrary to truth and based on mistake).

- Critique and Ongoing Discussion: The PDF commentary offers a detailed critique and discussion of this ruling:

- Soundness of Estoppel as a Basis: The commentator questions whether estoppel is always a fitting rationale, as junior creditors might not always rely on the initially stated amount to their detriment, especially if the applying creditor could have filed a separate auction application for the remainder of the debt anyway (which would negate actual detrimental reliance on the initial partial claim). It's also difficult to infer a clear intention to waive the remainder from a merely partial claim in all circumstances.

- Potential Imbalance: There's a potential imbalance if other creditors (who merely file demands for distribution without initiating the auction) are allowed more flexibility in amending their claimed amounts in their calculation statements compared to the applying secured creditor.

- Broadness of the "Error" Exception: If proving that the initial statement was "contrary to the true amount" is sufficient to infer an error allowing correction, the exception might become quite broad in practice, potentially undermining the goal of procedural stability if many cases lead to full lawsuits to adjust distributions.

- Interaction with Unjust Enrichment Claims: The commentator also points to a 1991 Supreme Court decision that allowed a mortgagee who failed to object to an incorrect distribution plan to later sue other creditors for unjust enrichment to recover amounts they should have received. If the current 2003 ruling restricts expansion in the auction but the creditor might still have a later unjust enrichment claim, it could lead to protracted disputes and undermine the finality of the distribution. The commentator suggests that a more straightforward approach might be to allow claim expansion more liberally within the auction process itself (perhaps with stricter rules for objecting), and then to bar subsequent unjust enrichment claims for those who failed to properly assert their rights in the auction. This, it is argued, might better serve overall procedural efficiency and finality.

Conclusion

The 2003 Supreme Court decision represents a significant development in Japanese law concerning the enforcement of security interests. It strikes a balance by largely maintaining the principle that an applying secured creditor is bound by their initially stated claim amount within the confines of the auction procedure itself, thereby upholding procedural stability and the reliance interests of other parties. However, it provides a crucial avenue for relief by allowing the creditor to seek an expansion of their claim in a subsequent "action of objection to distribution" if they can prove that their initial understatement was due to a genuine error or mistake and that their full claim is validly secured. This ruling underscores the Court's effort to prevent substantive rights from being irrevocably lost due to unintentional procedural missteps, while still channeling such corrective actions into a formal judicial proceeding.