Executive Pay in Japan: Avoiding “Unreasonably High” Compensation Pitfalls under the Corporation Tax Act

TL;DR

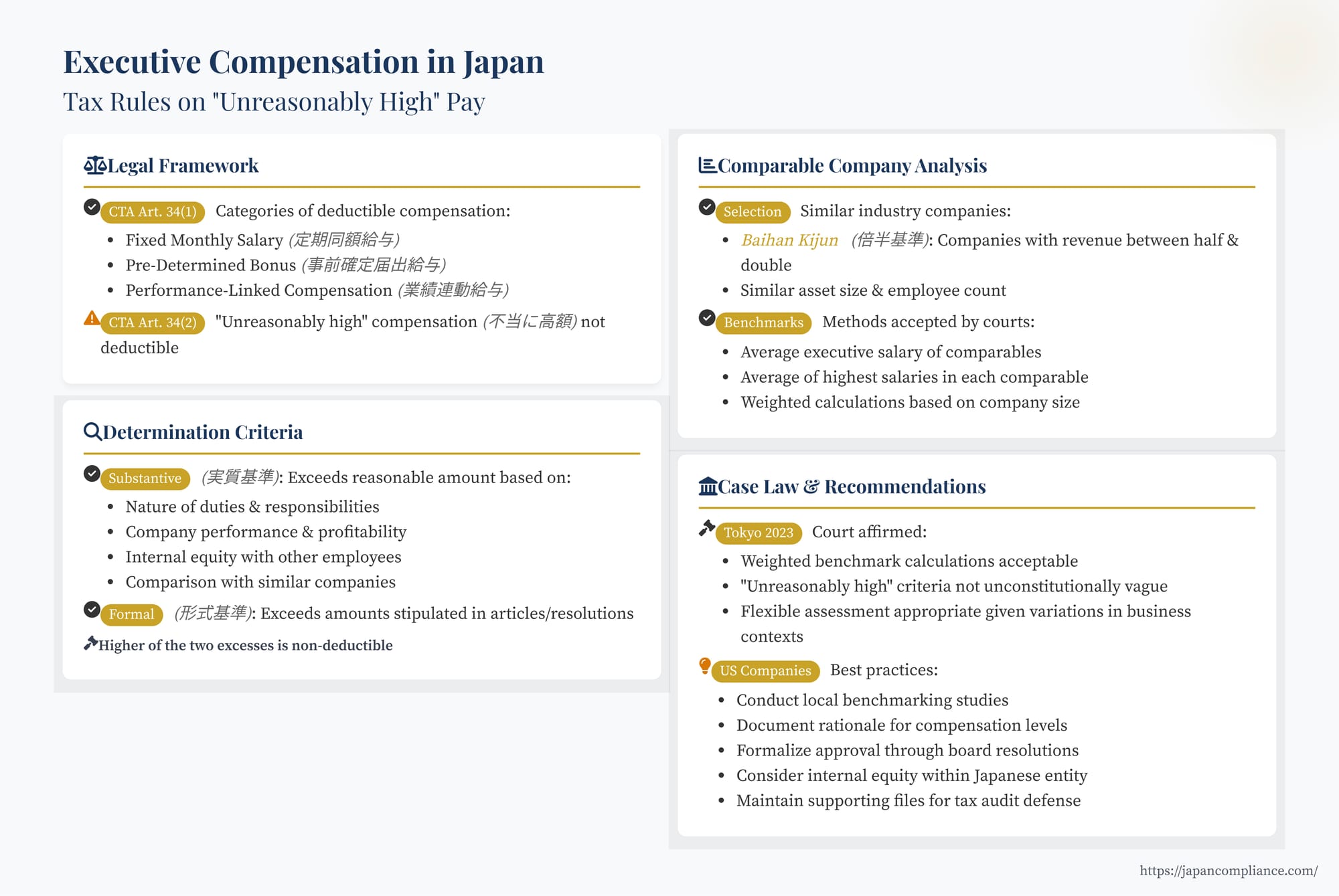

- Japan’s Corporation Tax Act allows deductions for executive pay only if the amount is not “unreasonably high.”

- Article 70 of the Enforcement Order applies dual tests: substantive benchmarking vs. formal limits.

- Courts (Tokyo 2023, Supreme Court 1997) uphold the rule; thorough benchmarking, board approvals and documentation are essential for US subsidiaries.

Table of Contents

- The Legal Framework: Deductibility under the Corporation Tax Act (CTA)

- The Challenge of Vagueness vs. Tax Legalism

- Determining the "Reasonable Amount": Focus on Comparables

- The Importance of Process and Documentation

- Implications for US Subsidiaries in Japan

- Practical Recommendations for Compliance

- Conclusion

Setting appropriate and competitive executive compensation is a critical task for any multinational corporation. When operating in Japan, US companies must not only consider market benchmarks and corporate governance norms but also navigate specific provisions within Japanese tax law that can limit the deductibility of executive salaries and bonuses. A key area of scrutiny is the concept of "unreasonably high" executive compensation under Japan's Corporation Tax Act (CTA), which can lead to significant, unexpected tax liabilities if not managed carefully.

This article examines the Japanese tax rules surrounding executive compensation deductibility, focusing on the criteria used to determine if pay is "unreasonably high," relevant case law, and practical implications for US companies setting compensation for executives in their Japanese subsidiaries.

The Legal Framework: Deductibility under the Corporation Tax Act (CTA)

Japan's Corporation Tax Act (法人税法 - hōjinzei hō) provides the primary rules governing the deductibility of corporate expenses, including executive compensation (役員給与 - yakuin kyūyo). The general approach is stricter than in the US, with specific conditions needing to be met for deductibility.

CTA Article 34(1): Categories of Deductible Compensation

Generally, for executive compensation to be deductible as a business expense, it must fall into one of the prescribed categories outlined in Article 34(1). The most common types include:

- Fixed Monthly Salary (定期同額給与 - teiki dōgaku kyūyo): Salaries paid in fixed amounts at regular intervals (typically monthly) without unjustified fluctuations.

- Pre-Determined Bonus (事前確定届出給与 - jizen kakutei todokede kyūyo): Bonuses where the payment date and amount are fixed in advance, determined by resolution at a shareholders meeting or similar body, and notified to the tax authorities by a specified deadline.

- Performance-Linked Compensation (業績連動給与 - gyōseki rendō kyūyo): Compensation linked to objective performance indicators, calculated based on disclosed formulas, and meeting specific requirements (often involving compensation committees and complex structuring, more common in listed companies).

Compensation that doesn't fit neatly into these categories (e.g., discretionary bonuses decided after the fact) is generally non-deductible.

CTA Article 34(2): The "Unreasonably High" Limitation

Crucially, even if compensation structurally qualifies under one of the deductible categories in Article 34(1), Article 34(2) imposes an amount-based limitation. It states that any portion of otherwise deductible executive compensation that is deemed "unreasonably high" (不相当に高額 - fusōtō ni kōgaku) will not be deductible for corporate tax purposes.

This provision acts as an anti-abuse measure, preventing companies (especially closely held ones) from artificially reducing taxable income by paying excessively large salaries or bonuses to executives, who might also be major shareholders.

CTA Enforcement Order Article 70: Defining "Unreasonably High"

The specifics of how "unreasonably high" is determined are laid out in Article 70 of the Corporation Tax Act Enforcement Order (法人税法施行令 - hōjinzei hō shikōrei). This article establishes a dual-test approach, comparing the actual compensation paid against benchmarks derived from both substantive and formal criteria:

- Substantive Criteria (実質基準 - jisshitsu kijun) (Art. 70(1)(a)): This assesses whether the compensation exceeds what is considered reasonable remuneration for the executive's actual duties performed. The assessment considers:

- The nature of the executive's duties and responsibilities.

- The company's financial performance (profitability, revenue).

- Salaries paid to other employees within the company (internal equity).

- Compensation levels for executives in comparable companies (external benchmarking) based on size, industry, etc.

Any amount exceeding the level deemed substantively reasonable is considered "unreasonably high" under this criterion.

- Formal Criteria (形式基準 - keishiki kijun) (Art. 70(1)(b)): This focuses on procedural aspects, such as whether the compensation exceeds amounts stipulated in the articles of incorporation or approved by shareholder resolutions. While less frequently the primary issue than substantive criteria, exceeding formally approved limits can also render compensation non-deductible.

The Higher Amount Prevails: Article 70 dictates that the amount deemed non-deductible is the larger of the excesses calculated based on the substantive criteria and the formal criteria. However, in practice, disputes and tax audits often center on the application of the more subjective substantive criteria.

The Challenge of Vagueness vs. Tax Legalism

Taxpayers have sometimes challenged the "unreasonably high" provision based on Article 84 of the Japanese Constitution, which embodies the principle of tax legalism (租税法律主義 - sozei hōritsu shugi) – requiring laws imposing taxes to be clearly defined by statute. The argument is that terms like "unreasonably high," "nature of duties," and "circumstances" are too vague, granting excessive discretion to tax authorities.

However, Japanese courts, including the Supreme Court (e.g., judgment of March 25, 1997) and more recently the Tokyo District Court in a case decided March 23, 2023, have consistently rejected these challenges. The courts acknowledge that these terms necessarily involve some level of assessment and breadth, given the difficulty of legislating precise numerical limits for all possible scenarios. They have held that the criteria, particularly when viewed in conjunction with the factors outlined in the Enforcement Order, are sufficiently concrete and objective to provide adequate predictability for taxpayers and to prevent arbitrary enforcement. The courts recognize that a rigid, fixed cap could lead to unfairness in individual cases, thus necessitating a degree of flexible assessment based on established factors.

Interestingly, in the 2023 Tokyo case, the taxpayer also argued that the tax authority's decision was flawed because the government presented a different calculation for the "reasonable" salary amount during the litigation compared to the amount used in the original tax reassessment. The court dismissed this, stating that some variation in evaluation based on the same underlying facts and legal standard is foreseeable given the assessment's nature, and it didn't constitute an improper change of reasoning invalidating the assessment itself, especially within the context of tax litigation principles in Japan.

Determining the "Reasonable Amount": Focus on Comparables

Since the substantive criteria rely heavily on external benchmarking, understanding how tax authorities and courts approach the comparable company analysis is critical.

1. Selecting Comparable Companies (類似法人 - ruiji hōjin):

There's no single legally mandated method, but tax authorities often employ objective filters to identify a peer group. A common method mentioned in case law, including the 2023 Tokyo decision, is the baihan kijun (倍半基準 – literally "double-half standard"). This involves selecting companies in the same or similar industry whose revenue falls within a certain range of the taxpayer company's revenue (e.g., between half and double). Other factors like asset size, employee count, and business specifics may also be considered. Courts have generally found methods like the baihan kijun to be reasonable ways to establish a relevant peer group for comparison.

2. Calculating the Benchmark Amount:

Once comparables are selected, the "reasonable" compensation benchmark is derived from their data. Again, methods vary:

- Average Salary: Calculating the average executive salary among the comparables.

- Average of the Highest Salaries: Calculating the average of the single highest-paid executive's salary within each comparable company. This method has been accepted in recent court decisions as potentially reasonable.

- Weighted Calculations: Adjusting benchmark figures (like the average-of-the-highest) based on weighted factors reflecting differences in sales volume, profitability, or other relevant metrics between the taxpayer and the comparable group. The 2023 Tokyo case notably affirmed the reasonableness of such a weighted calculation for some executives in that specific case, marking it as potentially the first court decision to explicitly do so.

3. No Absolute Formula:

It is crucial to understand, as emphasized by the court in the 2023 case, that these methods (like baihan kijun or using the average-of-the-highest salary) are not rigid legal rules or absolute formulas. They are tools used in the fact-finding process to arrive at a reasonable benchmark. The appropriateness and reasonableness of any specific method ultimately depend on the facts and circumstances of the individual case. Tax authorities and courts retain discretion in determining the most suitable approach.

The Importance of Process and Documentation

Given the subjective nature of the substantive criteria assessment, robust internal processes and thorough documentation are paramount for defending compensation levels against challenges.

- Formal Approval: Compensation amounts, especially those potentially seen as high, should be formally approved through appropriate corporate governance channels (e.g., board of directors, compensation committee if one exists, shareholder meeting where required). Clear resolutions should be recorded in minutes.

- Rationale Documentation: The reasons for setting compensation at a particular level should be documented at the time the decision is made. This documentation should ideally link the compensation to:

- The executive's specific duties, responsibilities, and experience.

- The company's performance and strategic goals.

- Relevant market benchmarks (including data sources used for comparison).

- Individual performance evaluations.

- Consistency: Compensation policies should be applied consistently. Ad-hoc or poorly justified deviations can raise red flags.

- Use of External Experts: Engaging compensation consultants to provide independent benchmarking data and advice can add credibility to the company's decisions, although reliance on consultants alone doesn't guarantee deductibility if the final amount is still deemed unreasonable based on other factors.

Implications for US Subsidiaries in Japan

The "unreasonably high" compensation rules present specific challenges and considerations for US companies operating subsidiaries in Japan:

- Aligning Global vs. Local Norms: US executive compensation levels and structures (e.g., higher cash components, aggressive equity incentives) often differ significantly from traditional Japanese practices. Importing a US-style package directly into a Japanese subsidiary without considering local benchmarks and the CTA's substantive criteria significantly increases the risk of a portion being deemed "unreasonably high" and non-deductible.

- Increased Tax Burden: A successful challenge by the tax authorities results in the disallowance of the excessive portion as a deductible expense, leading to higher corporate income tax liability for the Japanese subsidiary.

- Scrutiny in Audits: Executive compensation is a common focus area during tax audits in Japan, especially for subsidiaries of foreign parents or in closely held structures.

- Need for Localized Strategy: Compensation for executives in Japanese subsidiaries should be determined with careful consideration of Japanese market data, performance metrics relevant to the Japanese entity, and the specific requirements of the CTA. Relying solely on global compensation bands may not be sufficient justification.

- Documentation is Defense: In the event of a tax audit or challenge, well-documented board resolutions, supporting benchmark data, and a clear rationale linking pay to duties and performance are the primary means of defending the compensation's reasonableness.

Practical Recommendations for Compliance

To mitigate the risk of executive compensation being disallowed as "unreasonably high" in Japan, US companies should:

- Conduct Local Benchmarking: Regularly benchmark executive positions against relevant Japanese companies (considering industry, size, location, and profitability). Use credible data sources.

- Define Roles Clearly: Ensure job descriptions and documented responsibilities for executives in the Japanese subsidiary are clear, accurate, and reflect their actual duties.

- Formalize Decision-Making: Utilize formal board or compensation committee processes for setting and approving executive pay. Document decisions and rationale thoroughly in meeting minutes.

- Maintain Supporting Files: Keep records of benchmarking studies, performance evaluations, company financial data, and internal analyses used to justify compensation levels.

- Link Pay to Performance (Carefully): While performance linkage is a positive factor, ensure performance metrics are objective and the link is clearly defined (especially if using performance-linked pay under Art. 34(1)).

- Consider Internal Equity: Be mindful of the relationship between executive pay and the compensation of other employees within the Japanese subsidiary. Large disparities may require stronger justification.

- Seek Local Tax Advice: Consult with Japanese tax professionals, particularly when setting compensation for top executives, implementing new incentive plans, or facing potential audits. They can provide insights into current enforcement practices and acceptable ranges.

Conclusion

While Japan's Corporation Tax Act allows for the deduction of executive compensation that meets specific formal requirements, the provision disallowing "unreasonably high" amounts represents a significant potential tax risk. This rule, grounded in substantive criteria related to duties, performance, and comparability, requires careful consideration, especially for US companies accustomed to different compensation norms. Proactive planning, robust justification based on both internal factors and external benchmarks, meticulous documentation, and a sensitivity to local practices are essential for effectively navigating these rules and ensuring the tax deductibility of executive compensation in Japanese subsidiaries.

- International Tax Risks in Japan: PE, Transfer Pricing, CFC & Pillar Two Guide for US Companies

- Director Liability and Corporate Donations in Japan: Balancing Philanthropy and Fiduciary Duty

- Mandatory Sustainability Reporting in Japan: FIEA Rules & ISSB Alignment for Global Companies

- National Tax Agency – Q&A on Executive Compensation Deductibility (Japanese)

- Tokyo Regional Tax Bureau – Guidance on “Unreasonably High” Salaries (PDF)