Executing Periodic Payment Orders in Japan: Supreme Court Clarifies 'Two-Week Rule' for Provisional Dispositions

Date of Supreme Court Decision: January 20, 2005

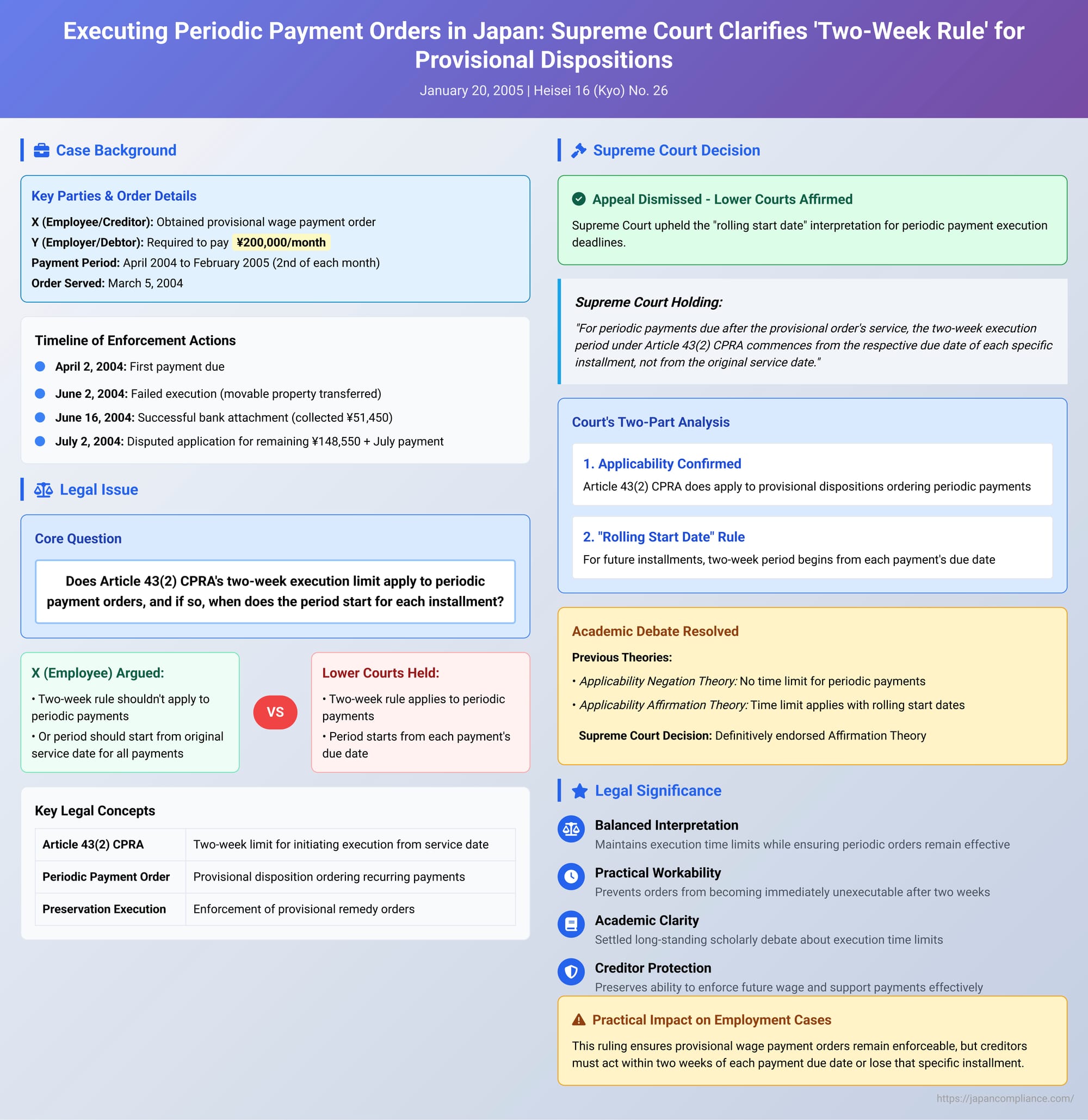

Provisional dispositions (仮処分 - karishobun) are a vital feature of the Japanese civil justice system, offering interim relief to protect a claimant's rights pending a final resolution of their case. When these dispositions order periodic payments, such as provisional wage payments or ongoing support, a critical question arises regarding the timeframe for their enforcement. Article 43, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA) generally imposes a strict two-week period for initiating the execution of a provisional order, starting from the date the order is served on the creditor. A 2005 Supreme Court of Japan decision (Heisei 16 (Kyo) No. 26) provided much-needed clarity on how this rule applies to future installments in such periodic payment orders.

The Factual Context: Provisional Wage Payments and Enforcement Attempts

The case involved X, an employee (the creditor), who had obtained a provisional disposition order against their employer, Y (the debtor). This order mandated Y to make provisional wage payments to X, stipulating: "Y shall provisionally pay X ¥200,000 per month on the 2nd day of each month from April 2004 to February 2005."

This provisional disposition order was formally served on X, the creditor, on March 5, 2004.

X subsequently took steps to enforce this order:

- For the payment installment due on April 2, 2004:

- On June 2, 2004, X first attempted to execute the order against Y's movable property. This attempt failed because the targeted assets were found to have been transferred to a third party, and the execution was halted.

- Following this, on June 16, 2004, X applied for an attachment of Y's bank account (a monetary claim) to recover the April 2 payment. Through this action, X successfully collected ¥51,450.

- The Disputed Application: On July 2, 2004, X filed a new application for a writ of attachment against a different bank account belonging to Y. This application sought to recover:

- The outstanding balance of ¥148,550 for the April 2, 2004 installment ("Honken Seikyū Saiken" – the Claim in Question).

- The full amount due for the July 2, 2004 installment.

The Lower Courts' Interpretation: Due Date as the Starting Point for Each Installment

The Okayama District Court (the court of first instance handling the execution) and subsequently the Hiroshima High Court, Okayama Branch (the appellate court for execution matters) dismissed X's application with respect to the ¥148,550 sought for the April 2, 2004, installment.

The High Court's reasoning was that Article 43, Paragraph 2 of the CPRA, which imposes a two-week limit on initiating execution, does indeed apply to provisional dispositions ordering periodic payments. However, it held that for each specific periodic payment, the creditor must initiate the execution procedure within two weeks from that particular payment's due date. If this deadline is missed for any given installment, execution for that installment becomes impermissible. Applying this logic, X's attempt on July 2, 2004, to recover the balance of the April 2, 2004, payment was deemed too late (as more than two weeks had passed since April 2).

X filed a permitted appeal to the Supreme Court challenging this decision.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: A Pragmatic Approach to Periodic Payments

The Supreme Court, in its decision of January 20, 2005, dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' interpretation.

Core Holding: The Supreme Court established two key points:

- Article 43, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA), which stipulates that "Preservation execution may not be carried out when two weeks have elapsed from the date on which a preservation order was served on the creditor," does apply to provisional dispositions ordering periodic payments.

- For those periodic payments that become due after the date on which the provisional disposition order was initially served on the creditor, the two-week execution period stipulated in Article 43, Paragraph 2 is to be calculated not from the date of the original service of the order, but from the respective due date of each specific periodic payment.

Rationale Behind the Decision:

The Supreme Court's brief judgment did not elaborate extensively on its reasoning, but it aligns with the prevailing legal interpretation and the underlying purposes of the CPRA:

- Purpose of CPRA Article 43(2): This provision serves multiple functions. Provisional remedies are granted based on a summary showing of need and urgency, and they are, by nature, temporary. Allowing a creditor to initiate execution indefinitely after receiving such an order would be problematic. Circumstances relevant to the "necessity of preservation" or the adequacy of any security provided might change over time. If an execution based on outdated circumstances were permitted, it could lead to unjust outcomes. Furthermore, the rule encourages prompt action by creditors who claim an urgent need for protection; a creditor who does not act swiftly to execute might be seen as not truly requiring the urgent protection the provisional remedy system offers.

- The Problem with Literal Application to Periodic Payments: A strictly literal application of Article 43(2) to provisional orders for periodic payments would lead to an impractical and arguably absurd result. If the two-week execution period for all future installments always commenced from the date the initial order was served on the creditor, then any installment falling due more than two weeks after that service date would become immediately unexecutable. This would render such provisional orders for future payments largely ineffective and undermine their purpose, especially in cases like ongoing wage or support payments.

- The Adopted Interpretive Solution: To avoid this impractical outcome and ensure that provisional orders for periodic payments retain their efficacy, the Supreme Court adopted the interpretation that the two-week execution window "rolls" with each installment. For each payment that becomes due after the initial service of the order, a fresh two-week period for initiating execution commences from that specific installment's due date.

- Balancing Creditor and Debtor Interests: This interpretation strikes a balance. It provides a workable mechanism for creditors to enforce their rights to future periodic payments under the provisional order. At the same time, it maintains the underlying policy of Article 43(2) by requiring the creditor to act with reasonable promptness (within two weeks) once each specific installment becomes due and executable. It prevents the creditor from holding the threat of execution over the debtor indefinitely for past-due future installments without taking timely action.

Historical Context and Scholarly Debate

This Supreme Court decision settled a long-standing debate in Japanese legal scholarship and practice concerning the application of execution time limits to periodic payment provisional orders:

- Old Code of Civil Procedure: Similar issues were debated under the old Code of Civil Procedure, which had a comparable 14-day execution limit for provisional attachments (Article 749, Paragraph 2), a rule that was applied by analogy to provisional dispositions (via Article 756).

- "Applicability Negation Theory" (適用否定説 - tekiyō hitei setsu): One school of thought argued that the execution time limit should not apply at all to provisional dispositions ordering periodic payments. Proponents suggested that creditors should be able to execute for each installment once it fell due, without a strict two-week deadline from that due date. If a creditor unduly delayed execution, the debtor's remedy would be to apply for a revocation of the provisional disposition due to a "change in circumstances" (e.g., arguing that the continued necessity for the provisional payments had ceased). A key concern was the potential hardship on creditors if they were forced to repeatedly initiate execution for each individual payment under a tight deadline.

- "Applicability Affirmation Theory" (適用肯定説 - tekiyō kōtei setsu): The opposing view, which gradually became the dominant one in both academic circles and court practice even before this Supreme Court ruling, was that the execution time limit does apply. However, to make such orders workable, this theory proposed that for future installments, the two-week execution period should commence from the due date of each respective installment. This was seen as being consistent with the legislative intent of requiring promptness in execution while ensuring the provisional order could achieve its purpose. Within this theory, the prevailing understanding was also that missing the two-week deadline for one installment would only render that specific installment unexecutable under the original order; it would not invalidate the entire provisional order for subsequent future installments.

The 2005 Supreme Court decision definitively endorsed the "Applicability Affirmation Theory" with this "rolling start date" for each installment, thereby providing clear authority and resolving the theoretical uncertainty.

Nature of the Two-Week Execution Period

Legal commentary clarifies that the two-week period stipulated in CPRA Article 43(2) is a "statutory period" (法定期間 - hōtei kikan), not an "unalterable peremptory period" (不変期間 - fuhen kikan). Nevertheless, the prevailing view is that this period generally cannot be extended or shortened by court discretion. This is attributed to the provision's public interest nature—balancing the rights of creditors and debtors and promoting the prompt and orderly conduct of execution proceedings, which require formal and uniform handling.

Remaining Challenges and Legislative Considerations

Despite the clarity provided by the Supreme Court, legal commentators point to some remaining practical challenges:

- "Commencement of Execution": For a creditor to comply with the two-week limit, they must "commence" execution. This generally requires more than merely filing an application for an execution measure; the first concrete step of the execution process (e.g., for attaching a bank account, the service of the attachment order on the third-party bank) must typically occur within this window. Achieving this within two weeks can sometimes be challenging.

- Cost and Effort for Small Periodic Payments: Especially for provisional orders involving relatively small periodic payments (such as some forms of maintenance or partial wage payments), the expense and administrative burden of having to initiate separate execution proceedings for each installment within a tight two-week timeframe can be disproportionate and place a heavy load on the creditor.

- Legislative Developments for Similar Claims: It's noted that for certain types of claims, particularly family-related support obligations like child support, the Civil Execution Act was amended in 2003 (effective 2004) to introduce a system for a more comprehensive, "preliminary attachment" of future periodic payments (民事執行法151条の2 - Minji Shikkōhō Article 151-2). This reform has helped to alleviate some of the problems of repetitive execution for those specific claim types. Commentators have suggested that similar legislative solutions might be worth considering for other categories of periodic payments frequently ordered by provisional disposition, such as provisional wage payments or ongoing installments of accident compensation.

- Adequacy of the Two-Week Period: Some scholars have questioned whether the two-week period is realistically sufficient for creditors to identify a debtor's assets (especially when dealing with debtors who may try to conceal them) and to complete the necessary steps to commence execution. Suggestions have been made that a longer period, perhaps aligning with the one-month period found in some other legal systems like Germany, might be more appropriate. These, however, remain matters for potential future legislative consideration.

Concluding Thoughts

The January 20, 2005, Supreme Court decision provides indispensable guidance for the enforcement of provisional dispositions ordering periodic payments in Japan. By confirming that the two-week execution limit of CPRA Article 43(2) applies, but that the commencement of this period for future installments rolls forward to each respective due date, the Court adopted a pragmatic interpretation. This ruling effectively balances the underlying legislative policy of requiring reasonably prompt action by creditors seeking the protection of provisional remedies with the practical necessity of ensuring that orders for future periodic payments can be meaningfully enforced. While it settles a key legal debate, the decision also implicitly highlights ongoing practical challenges in this area, some of which may invite further legislative attention to streamline the enforcement process for recurring obligations established by provisional court orders.