Exclusionary Conduct in Copyright Licensing: Japan's JASRAC Blanket License Decision (2015)

Introduction

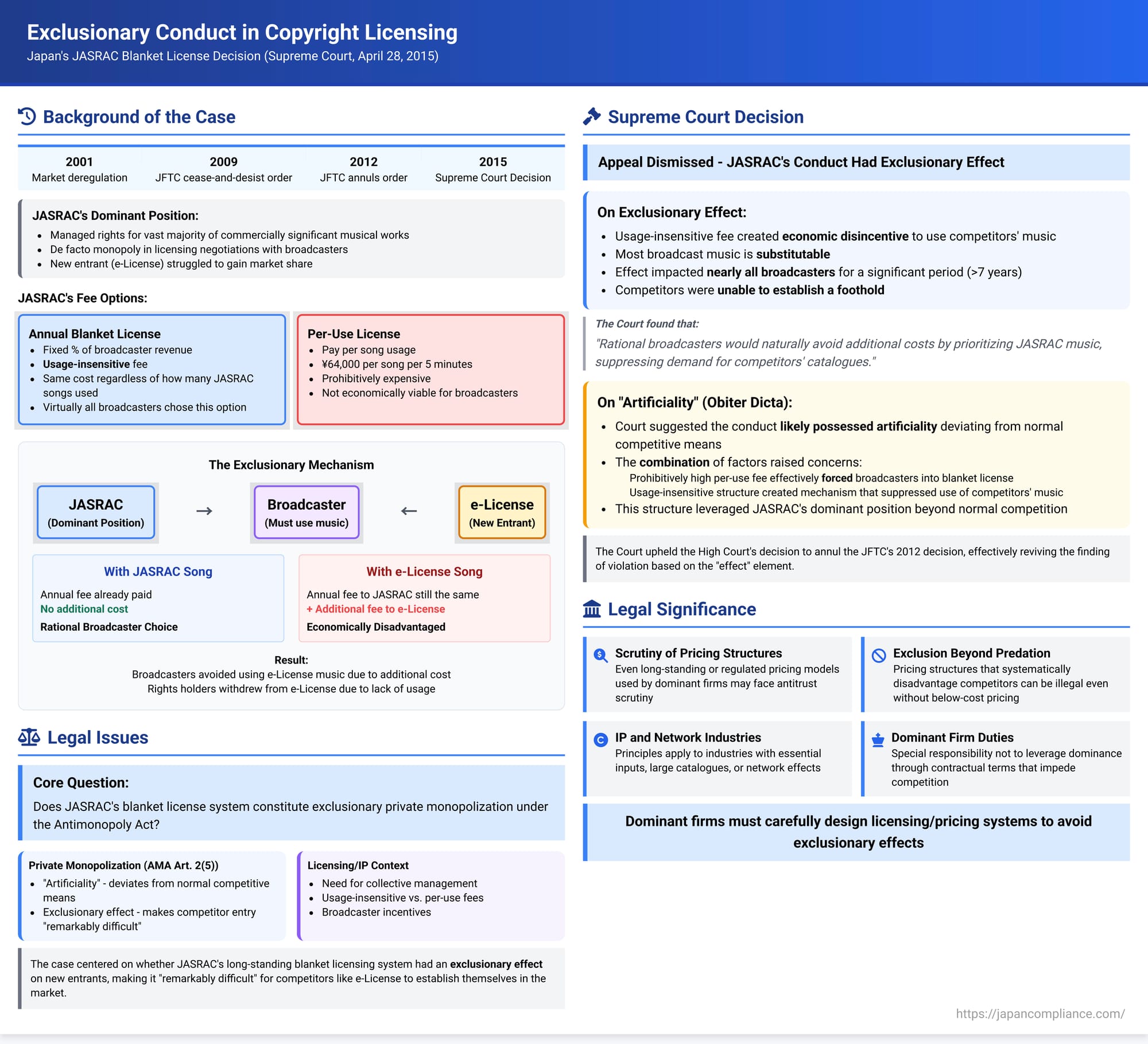

On April 28, 2015, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered an important judgment in Case No. Heisei 26 (Gyo-Hi) No. 75, addressing the application of Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA) to the licensing practices of the country's dominant music copyright collective management organization, anonymized here as J Corp. (representing JASRAC). The case specifically examined whether J Corp.'s long-standing system of charging broadcasters a single "blanket" fee, regardless of how much of J Corp.'s music they actually used relative to competitors' music, constituted illegal "exclusionary private monopolization" under AMA Article 2(5) and Article 3 by hindering the entry and operation of rival copyright management organizations.

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed J Corp.'s appeal, upholding a Tokyo High Court decision which had found that J Corp.'s blanket licensing fee structure did have the effect of making competitor entry remarkably difficult. While the Court did not make a final ruling on all elements of the violation (remanding implicitly for further consideration of "artificiality"), its analysis of the exclusionary effects of J Corp.'s system provides significant guidance on how antitrust law scrutinizes the conduct of dominant firms, particularly in intellectual property licensing and network industries.

Background: Music Copyright Management and Private Monopolization

- Copyright Collectives: Organizations like J Corp. manage copyrights on behalf of numerous authors and publishers (rights holders). They license the use of musical works to users (like broadcasters, streaming services, shops) and collect royalties, which are then distributed back to the rights holders. This collective management is often necessary because tracking and licensing millions of individual song uses would be impractical for both users and rights holders.

- Japanese Market Context: Historically, J Corp. was the sole government-approved entity managing music copyrights in Japan. Following deregulation in 2001 (enactment of the Copyright Management Business Act), new entrants were allowed, but J Corp. retained management rights for the vast majority of commercially significant musical works, giving it a de facto monopoly or dominant position in licensing negotiations with major users like broadcasters.

- Blanket Licensing: Broadcasters use a vast quantity and variety of music. Negotiating licenses for each song individually is infeasible. Therefore, the standard industry practice was for broadcasters to obtain a "blanket license" (hōkatsu kyodaku) from J Corp., granting the right to use any song in J Corp.'s extensive repertoire.

- J Corp.'s Fee Structure: J Corp.'s approved royalty rules (shiyōryō kitei) offered two main options for broadcasters:

- Annual Blanket License with Blanket Collection (Honken Hōkatsu Chōshū): Users paid an annual fee, typically calculated as a fixed percentage of the broadcaster's total revenue. Crucially, this fee was independent of the actual number or proportion of J Corp.-managed songs used by the broadcaster relative to songs managed by other organizations.

- Per-Use License with Per-Use Collection (Kobetsu Chōshū): Users could theoretically license songs individually, paying a per-use royalty (tan'i shiyōryō). However, J Corp.'s regulated per-use rate was set at such a high level (e.g., ¥64,000 per song per 5 minutes for nationwide broadcast) that it was economically prohibitive for broadcasters using music regularly.

- The Result: Due to the prohibitive cost of the per-use option, virtually all broadcasters opted for the annual blanket license with the revenue-based blanket collection method. This entire system of licensing and collection by J Corp. constituted "the conduct in question" (honken kōi) scrutinized in this case.

- Exclusionary Private Monopolization (AMA Art. 2(5), Art. 3): As established in the 2010 NTT East FTTH case, this violation requires conduct by a dominant firm that (a) deviates from normal competitive means due to its "artificiality" and (b) has the effect of making competitor entry "remarkably difficult," thereby causing a substantial restraint of competition (i.e., maintaining or strengthening market power).

Facts of the JASRAC Case

- Competitor Entry: Following deregulation, new copyright management organizations, including Company E (representing e-License, the plaintiff who sued the JFTC in the High Court), entered the market. Company E secured management rights for songs from certain rights holders (like D Group, representing Avex Group) and sought to license these songs to broadcasters, typically proposing a per-use fee structure.

- The Exclusionary Mechanism: Broadcasters already paying J Corp.'s revenue-based blanket fee faced a dilemma. If they used a song managed by Company E, they would have to pay an additional fee to Company E (likely on a per-use basis). Since their payment to J Corp. remained the same regardless of whether they used a J Corp. song or a Company E song for a particular slot (because the J Corp. fee was usage-insensitive), using a Company E song meant their total music royalty expenditure would increase.

- Impact on Competition: Given that most background music or incidental music used in broadcasting is substitutable (i.e., a broadcaster can often choose from several suitable tracks), broadcasters had a strong economic incentive to minimize costs by primarily using songs from J Corp.'s repertoire, for which they were already paying the blanket fee. This resulted in suppressed demand for music managed by Company E and other potential entrants, hindering their ability to gain traction in the broadcast market. Evidence presented included statements from broadcasters indicating they avoided using non-J Corp. music due to the additional cost, and the fact that D Group ultimately withdrew its catalogue from Company E due to the lack of broadcast usage and revenue.

- JFTC Proceedings:

- In 2009, the JFTC issued a cease-and-desist order against J Corp., finding that "the conduct in question" (the blanket licensing system) constituted exclusionary private monopolization.

- J Corp. requested an administrative hearing (shinpan).

- In 2012, the JFTC commissioners, acting in their adjudicative capacity, issued a decision (shinketsu) annulling the 2009 order. They concluded that while the system might disadvantage competitors, it did not rise to the level of making their market entry "remarkably difficult" and thus lacked the necessary exclusionary effect.

- High Court Appeal: Competitor Company E challenged the JFTC's 2012 decision in the Tokyo High Court. The High Court sided with Company E, finding that the conduct did indeed have the effect of making competitor entry remarkably difficult, and therefore annulled the JFTC's 2012 decision (effectively reviving the finding of violation based on the "effect" element). J Corp. intervened in the High Court case and subsequently appealed the High Court's ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 2015 Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court dismissed J Corp.'s appeal, thereby agreeing with the High Court that J Corp.'s conduct had the requisite exclusionary effect.

- Standard for Exclusion (Reaffirmation): The Court reiterated the legal standard for exclusionary conduct established in the 2010 NTT East case: it requires both "artificiality deviating from normal competitive means" and the "effect of making competitor entry remarkably difficult," assessed by comprehensively considering various factors.

- Analysis of Exclusionary Effect: The Court affirmed the High Court's finding that J Corp.'s conduct did have the effect of making competitor entry remarkably difficult. Its reasoning mirrored the High Court's and emphasized:

- Market Realities: J Corp.'s overwhelming dominance meant broadcasters realistically had to take a license from J Corp.

- Substitutability: Most music used in broadcasting is substitutable, allowing broadcasters to choose alternatives if one becomes relatively more expensive.

- Economic Disincentive: The usage-insensitive nature of J Corp.'s blanket fee meant using competitor songs imposed an additional cost layer, making competitor music relatively more expensive.

- Impact on Broadcaster Choice: Rational broadcasters would naturally avoid this additional cost by prioritizing J Corp. music, suppressing demand for competitors' catalogues.

- Scope and Duration: This effect impacted nearly all broadcasters due to the ubiquity of the blanket license and persisted for a significant period (over 7 years), hindering competitors like Company E from establishing a foothold.

- The "Artificiality" Element (Obiter Dicta): Although the appeal before the Supreme Court was formally only about the "effect" element (as that was the basis for the High Court's decision and the JFTC's 2012 decision), the Supreme Court included significant commentary (obiter dicta, non-binding remarks) on the "artificiality" element.

- It suggested that J Corp.'s conduct likely possessed the necessary artificiality deviating from normal competitive means.

- The reasoning pointed to the combination of:

- Setting the alternative per-use fee at a prohibitively high level, effectively forcing broadcasters into the blanket license system and eliminating choice regarding the collection method.

- Implementing a blanket collection method where the fee was insensitive to actual usage, thereby creating the mechanism that suppressed the use of competitors' music.

- The Court suggested that this structure, leveraging J Corp.'s dominant position and structuring fees to disadvantage rivals, appeared to go beyond normal competitive practices, "absent special circumstances" (which would need to be examined in subsequent proceedings).

- Procedural Outcome: By dismissing J Corp.'s appeal on the "effect" issue, the Supreme Court upheld the High Court's decision to annul the JFTC's 2012 decision. This procedurally reopened the case before the JFTC, requiring it to consider the remaining elements of private monopolization, particularly "artificiality" and potentially any justifications J Corp. might raise, in light of the now-established exclusionary effect. (As noted in legal commentary, J Corp. subsequently withdrew its administrative appeal, allowing the original 2009 cease-and-desist order finding a violation to become final).

Discussion: Implications for Dominant Firms and Licensing Models

The 2015 JASRAC decision offers important lessons regarding the application of AMA monopolization rules:

- Scrutiny of Dominant Firm Pricing Structures: The case demonstrates that antitrust authorities and courts will scrutinize pricing and licensing models used by dominant firms, even if those models have been long-standing or are based on regulated tariffs. The focus is on the effect on competition.

- Exclusion Beyond Predation: It confirms that conduct can be deemed exclusionary even if it doesn't involve pricing below cost (traditional predation). A price structure that systematically disadvantages competitors by manipulating user incentives (like the usage-insensitive blanket fee here) can be found illegal if it significantly hinders competitor entry or viability.

- Leveraging Dominance: The Court's comments on "artificiality" highlight the concern with dominant firms leveraging their power – here, the near-essential nature of J Corp.'s repertoire – through contractual terms or pricing structures that reinforce that dominance by making it harder for rivals to compete on the merits. The coupling of the blanket license with the specific fee structure was seen as potentially coercive.

- Relevance for IP and Network Industries: The principles regarding blanket licensing, essential inputs (large music catalogues), and network effects are relevant to other industries involving intellectual property or network infrastructure where dominant firms license access or content to downstream players.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2015 judgment in the JASRAC case provides significant clarification on how Japan's prohibition on exclusionary private monopolization applies to the complex licensing practices of dominant firms, particularly in the realm of intellectual property. By affirming that J Corp.'s usage-insensitive blanket licensing fee for broadcasters had the effect of substantially hindering competitors, and strongly suggesting that the overall fee structure possessed the requisite "artificiality," the Court reinforced the AMA's role in policing conduct that leverages market dominance to unfairly impede competition, even without overt predatory pricing. The case serves as a key precedent for dominant firms designing licensing or pricing systems, emphasizing the need to consider their potential impact on competitor viability and market entry.