Evicting Disruptive Occupants from Condominiums: Who Gets to "State Their Case"? A 1987 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Yakuza Presence

Date of Judgment: July 17, 1987

Case Number: 1987 (O) No. 444 (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench)

Introduction

Maintaining a peaceful and orderly living environment is paramount in Japanese condominiums, where residents live in close proximity and share common facilities. However, the actions of a single unit owner or, more commonly, an occupant (such as a tenant), can severely disrupt this environment. Japan's Condominium Ownership Act (COA) provides powerful legal remedies for management associations to address such situations, including, in extreme cases, the ability to seek a court order to terminate an occupant's lease and compel them to vacate the premises.

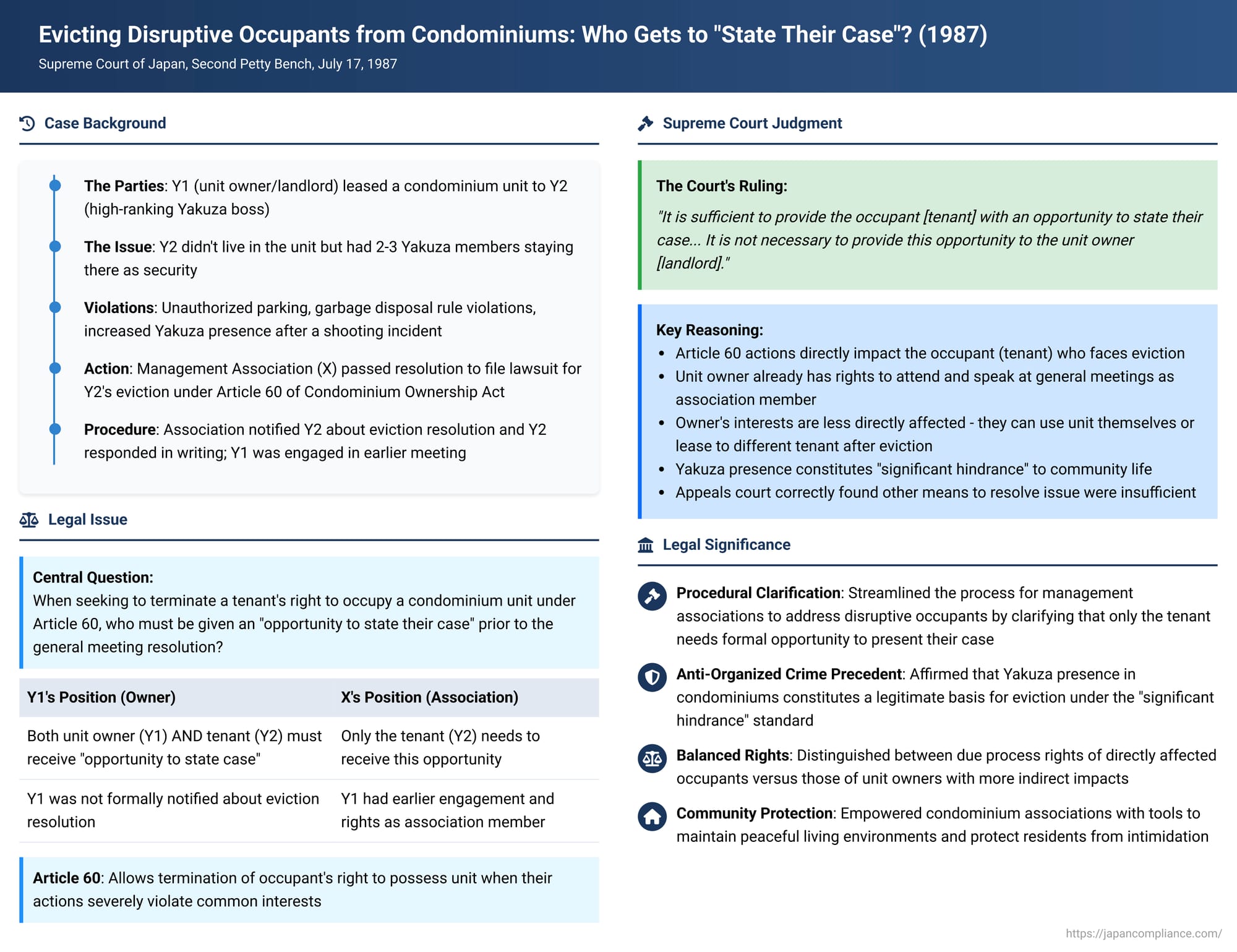

A significant Supreme Court decision on July 17, 1987, dealt with such a case, involving the presence of a high-ranking organized crime (Yakuza) boss as a tenant in a residential condominium. Beyond the substantive issue of whether such a presence justified eviction, the case provided crucial clarification on a key procedural requirement: when a management association seeks to take this drastic step, who must be given a formal "opportunity to state their case" (弁明の機会 - benmei no kikai) before the authorizing general meeting resolution is passed? Specifically, does this right extend to the unit owner (the landlord) in addition to the problematic occupant (the tenant)?

Facts of the Case

The dispute took place in "the Condominium," a building designated for residential use only.

The Parties and the Lease:

- Y1 was the owner of a private unit ("the Unit") within the Condominium.

- Y1 leased the Unit to Y2 for purported residential purposes.

- Y2 was identified as a prominent and influential boss within a Yakuza group affiliated with the Yamaguchi-gumi, Japan's largest organized crime syndicate.

Disruptive Conduct and Yakuza Presence:

- Although Y2 had leased the Unit ostensibly for residential use, he did not live there with his family. Instead, the Unit was constantly occupied by at least two to three members of his Yakuza group. These individuals were present to provide Y2 with security and personal assistance, effectively living in the Unit.

- Y2 and these accompanying group members were alleged to have repeatedly violated the Condominium's bylaws and rules. These violations included unauthorized use of parking spaces and disregard for garbage disposal regulations.

- The situation escalated following a highly publicized incident: the shooting death of the overall leader of the Yamaguchi-gumi. In response to this, and presumably fearing retaliatory attacks from rival Yakuza organizations, Y2 reportedly increased the number of his group members staying in the Unit. This heightened presence of Yakuza members further exacerbated the existing problems and undoubtedly increased unease among other residents.

Management Association's Action:

X was the manager (管理者 - kanrisha) of the Condominium's Management Association ("the Association"). Concerned about the ongoing disruptions and the inherent risks associated with Y2's presence, the Association decided to take action.

- A general meeting of the unit owners was convened, and a resolution was passed authorizing X to file a lawsuit under Article 60, Paragraph 1 of the COA. This article allows for legal action to terminate an occupant's right to possess a unit (e.g., by terminating their lease) and to demand that the occupant vacate and hand over the unit if their actions are gravely contrary to the common interests of unit owners.

- Procedural Steps Regarding "Opportunity to State Case":

- Approximately two months before the general meeting that authorized the lawsuit, the Association had engaged with Y1 (the unit owner/landlord) and heard Y1's views on the matter at a prior meeting.

- About two weeks before the crucial general meeting, the Association sent a formal written notice to Y2 (the tenant). This notice informed Y2 that an extraordinary general meeting was being convened for the specific purpose of passing a resolution to seek his eviction from the Unit.

- Y2 responded to this notice in writing, denying that his actions constituted any violations of the Condominium's rules or posed any danger to other residents.

Defenses Raised by Y1 and Y2:

In the ensuing lawsuit brought by X, Y1 and Y2 raised several defenses:

- Lack of Opportunity for Y1: Y1, the unit owner and landlord, argued that Y1 had not been given a formal opportunity to state their case before the general meeting passed the resolution authorizing the lawsuit against Y2.

- Insufficient Notice to Y2: Y2 argued that the notice informing Y2 of the opportunity to state his case did not provide specific, concrete details of the alleged violations that formed the basis of the proposed action.

- Substantive Requirements Not Met: Both Y1 and Y2 contended that Y2's actions did not meet the stringent substantive requirements set out in COA Article 60, Paragraph 1. They argued that Y2's conduct did not cause a "significant hindrance" to the common life of other unit owners, and that other, less drastic, methods for resolving any issues had not been exhausted.

Lower Court Rulings:

Both the first instance court (Yokohama District Court) and the appellate court (Tokyo High Court) ruled in favor of X, the Association manager.

- They held that it was not necessary under the COA to provide Y1 (the unit owner/landlord) with a formal "opportunity to state their case" when the action under Article 60 was directed at the occupant (Y2).

- Regarding the notice to Y2, the courts found that, given the ongoing history of the Association communicating with Y2 about his specific violations and previously requesting him to submit a written pledge to comply with the rules, Y2 was sufficiently aware of the nature and specifics of the complaints against him.

- On the substantive issue, both lower courts concluded that the conduct of Y2 and his associates did indeed meet the requirements of COA Article 60, Paragraph 1. They found that Y2's actions were contrary to the common interests of the unit owners, caused a significant hindrance to their common life, and that other means of resolving the problem were unlikely to be effective.

Y1 and Y2 appealed these decisions to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of July 17, 1987, dismissed the appeals lodged by Y1 and Y2, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions.

Primary Holding: Opportunity to State Case Required Only for the Occupant in Article 60 Actions:

The most significant part of the Supreme Court's ruling addressed the procedural question of who must be afforded an opportunity to state their case.

- The Court unequivocally stated: "When all unit owners or a management association corporation brings an action based on Article 60, Paragraph 1 of the Condominium Ownership Act, seeking the termination of a contract under which an occupant (占有者 - sen'yūsha) uses or profits from a private unit and the handover of said private unit, it is sufficient, as a prerequisite for the general meeting resolution authorizing such suit, to provide the said occupant with an opportunity to state their case in advance, in accordance with Article 58, Paragraph 3, as applied mutatis mutandis by Article 60, Paragraph 2 of the Act. It is not necessary to provide an opportunity to state their case to the unit owner (区分所有者 - kubun shoyūsha) who is allowing the said occupant to use or profit from the said private unit under such contract."

- The Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment on this specific point to be correct and fully endorsed it.

On Substantive Requirements and Other Procedural Claims:

- Regarding the substantive issue of whether Y2's actions justified the eviction order, the Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' findings of fact and their legal conclusions. It affirmed that the evidence supported the determination that Y2 (the tenant) had committed acts contrary to the common interests of the unit owners as defined in COA Article 6, Paragraph 1 (applied via Article 6, Paragraph 3 to occupants).

- It also agreed that these acts caused a significant hindrance to the common life of the unit owners, and that it was difficult to eliminate this hindrance by other means to ensure the proper use of common areas and maintain the community's common life.

- The Supreme Court dismissed the appellants' other arguments concerning alleged procedural irregularities or misinterpretations of facts. It found these arguments to be either matters falling within the lower courts' discretion in evaluating evidence or based on interpretations of facts not supported by the trial record.

Analysis and Broader Implications

This 1987 Supreme Court decision is a landmark for several reasons, particularly concerning the governance of condominiums and the tools available to address serious disruptions.

1. Significance of the Ruling:

- Clarification of Procedural Requirements for COA Article 60: The judgment provided definitive clarity on the scope of the "opportunity to state one's case" requirement in actions targeting disruptive occupants. By limiting this formal procedural step to the occupant themselves, it streamlined what can be a complex and urgent process for management associations.

- Affirmation of Strong Measures Against Organized Crime Presence: The case was one of the early and highly publicized instances where the Japanese legal system, through the COA, affirmed the ability of ordinary citizens in a condominium to take decisive action to exclude members of organized crime whose presence and associated activities were detrimental to their community. This had significant societal implications.

- Upholding Substantive Grounds for Eviction: The consistent finding by all three court levels that the presence and activities of a Yakuza group could meet the high threshold for "significant hindrance" under COA Article 60(1) was crucial. It confirmed that the law could be used to address not just overt illegal acts but also the pervasive fear, intimidation, and disruption associated with an organized crime presence in a residential setting.

2. The COA Framework for Addressing Rule Violations:

The COA provides a tiered system of remedies against unit owners or occupants who violate rules or act against common interests:

- Article 6, Paragraph 1: A general prohibition against any unit owner engaging in acts harmful to the building's preservation or any other acts "contrary to the common interests of unit owners" concerning the management or use of the building. Article 6, Paragraph 3 extends this prohibition to occupants.

- Article 57: Allows other unit owners (collectively) or the management association to seek an injunction to stop or prevent violations of Article 6(1).

- Article 58: Provides for a court order prohibiting a unit owner from using their own private unit for a certain period, in severe cases. This requires a general meeting resolution by a three-fourths majority of both unit owners and voting rights, and the owner must be given an opportunity to state their case.

- Article 59: In the most extreme cases involving a unit owner, allows for a court-ordered auction of that owner's unit and their ownership rights. This also requires a three-fourths majority resolution and an opportunity for the owner to state their case.

- Article 60 (the provision central to this case): Specifically targets occupants (who are not unit owners, e.g., tenants, family members of owners). It allows for a court order terminating the occupant's right of possession (e.g., their lease) and requiring them to hand over the unit. The substantive conditions are similar to Article 59 (significant hindrance, other means insufficient). The procedural requirements (three-fourths majority resolution, opportunity for the occupant to state their case) are applied by analogy from Article 58.

3. Rationale for the "Opportunity to State Case" (弁明の機会 - benmei no kikai):

This procedural safeguard is mandated because actions under Articles 58, 59, and 60 have severe consequences for the individuals targeted.

- For Unit Owners (under Articles 58 & 59): Even though unit owners have rights to attend and speak at general meetings, this special "opportunity to state their case" ensures they are specifically made aware that drastic action is being contemplated against them personally and are given a dedicated chance to present their defense or explanation directly in relation to that proposed action. This is important because routine general meeting notices might not always reach every owner, or might not sufficiently detail the specific grounds for such a severe proposed measure against an individual.

- For Occupants (under Article 60): Occupants, like tenants, also face a profound impact – eviction from their dwelling. While COA Article 44, Paragraph 1 grants occupants the right to attend and state their opinions at general meetings on matters concerning their interests, there is no statutory mechanism ensuring they are formally notified of the meeting's agenda, time, and place. Therefore, the requirement to specifically provide them with an "opportunity to state their case" ensures they are not deprived of their right to be heard before a decision with such serious consequences is made.

4. Why Only the Occupant in Article 60 Actions?

The Supreme Court's decision to limit the formal "opportunity to state case" to the occupant in Article 60 proceedings aligns with the direct target and impact of this specific legal remedy.

- Focus of Article 60: The primary aim of an Article 60 action is to remove the problematic occupant whose actions are causing the disruption.

- Impact on the Unit Owner (Landlord): The unit owner (landlord) is not being deprived of their property ownership. They are only being prevented from continuing their contractual relationship with that particular disruptive occupant. Once the occupant is removed, the owner retains the right to use the unit themselves, lease it to a different, non-problematic tenant, or sell it. The impact on the owner, while potentially involving loss of rental income from that specific tenant, is less direct and less final than the impact on the occupant being evicted.

- Owner's Existing Rights: The unit owner, as a member of the condominium association, already possesses the right to attend the general meeting where the resolution for an Article 60 action is being debated, and to speak and vote on the matter. Their interests can be voiced through these existing channels.

- Nature of the Safeguard: The "opportunity to state case" is fundamentally a due process safeguard tied to the severity of the consequence of being excluded from one's dwelling or the condominium community – a consequence directly faced by the occupant in an Article 60 action.

5. The Form of the "Opportunity":

The judgment suggests that the "opportunity" does not rigidly require a personal appearance at the general meeting itself. In this case, Y2 (the tenant) had submitted a written response to the Association's notification. The crucial element is that the occupant is adequately informed of the allegations and the proposed action and is given a fair chance to present their side of the story before the unit owners make their decision. Practical and safety considerations, especially in cases involving potentially dangerous individuals (as in this Yakuza-related case), might make written submissions or hearings conducted outside the full general meeting more appropriate and effective.

6. Substantive Justification – The "Yakuza Exclusion" Aspect:

The consistent finding by all levels of the judiciary that the presence and activities of Y2 and his entourage constituted a sufficiently grave disruption to justify the application of COA Article 60 is highly significant. It demonstrates that the Japanese legal system views the infiltration of residential communities by organized crime as a serious threat to the common interests and peaceful life of residents, warranting strong countermeasures. The decision was not based merely on minor breaches of bylaws but on the overall atmosphere of intimidation, fear, and disruption that such a presence can create, particularly in the context of inter-gang violence.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1987 ruling in this case delivered critical clarifications on both procedural and substantive aspects of Japan's Condominium Ownership Act in the context of dealing with severely disruptive occupants. Procedurally, it streamlined the process for management associations by confirming that in an action to remove an occupant under Article 60, the formal "opportunity to state one's case" need only be provided to the disruptive occupant, not necessarily to the unit owner who is their landlord. Substantively, the case was a powerful affirmation that the presence and associated activities of organized crime figures within a residential condominium can indeed constitute an act "contrary to the common interests of unit owners" causing a "significant hindrance" to community life, thereby justifying the drastic remedy of terminating their occupancy rights and compelling their removal. This decision remains a vital precedent in safeguarding the living environment of condominium communities in Japan.