EU CBAM: Impact on US–Japan Supply Chains

TL;DR: The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) extends EU-ETS carbon pricing to cement, steel, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity and hydrogen imports. From 2026 importers must buy CBAM certificates unless a foreign carbon price is credited. US firms trading via Japan must map emissions data, renegotiate supply-chain contracts and budget for certificate costs.

Table of Contents

- How CBAM Works: Mechanism and Timeline

- Calculating the Burden: Embedded Emissions and Carbon Price Adjustments

- Rationale and Controversy: Leakage Prevention vs. Trade Impact

- Compatibility with International Trade Law (WTO)

- Implications for US Businesses Trading with Japan

- Navigating CBAM Compliance

- Conclusion: A New Dimension in Climate Policy and Trade

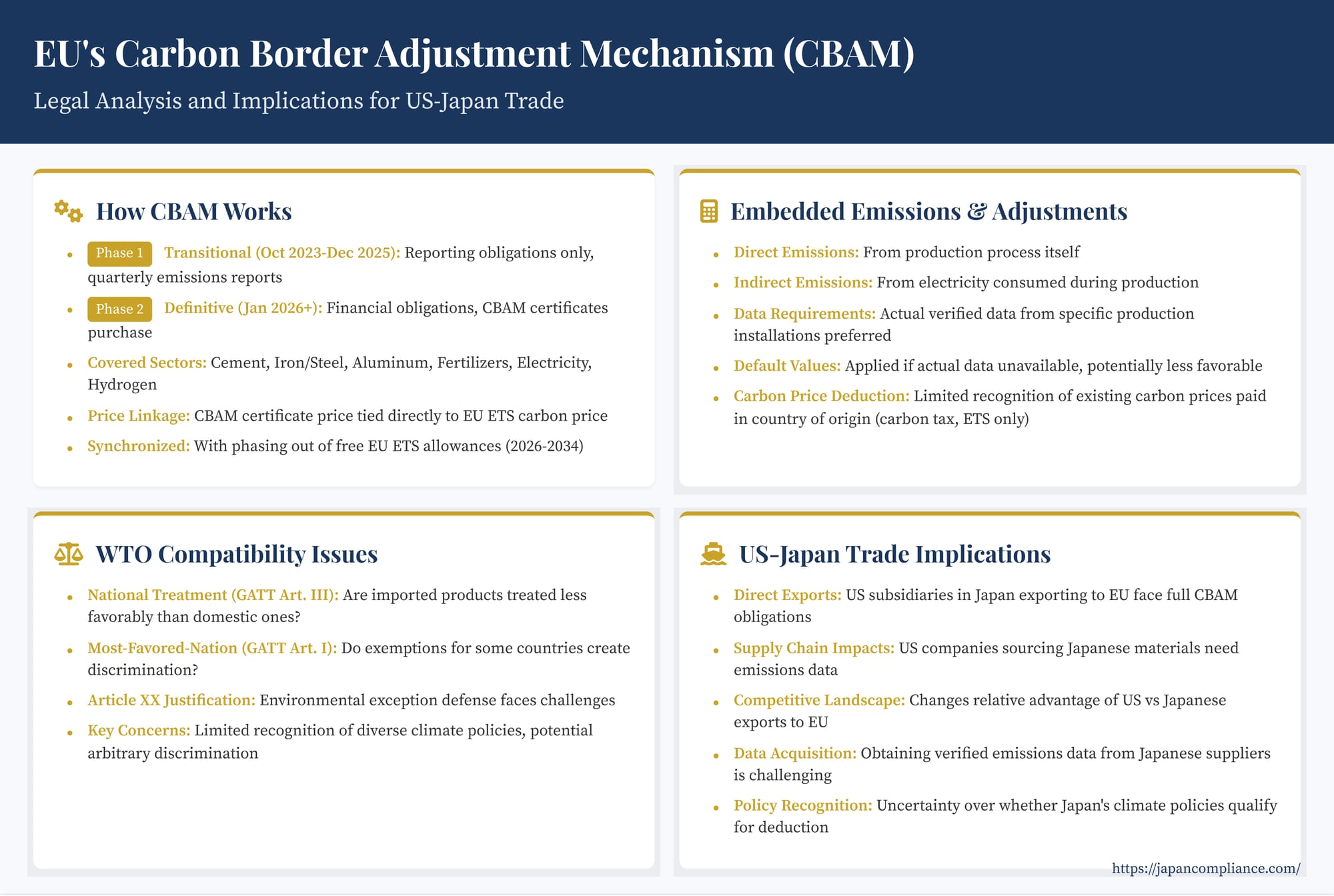

As part of its ambitious Green Deal, the European Union has implemented the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), a novel policy instrument designed to address the risk of "carbon leakage." Carbon leakage occurs when companies transfer production to countries with less stringent climate policies to avoid carbon costs, potentially leading to an increase in overall global emissions. CBAM aims to prevent this by effectively extending the carbon price faced by EU industries under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) to certain imported goods.

While ostensibly an environmental measure, CBAM has significant implications for international trade, potentially reshaping supply chains and creating new compliance burdens for businesses worldwide. Its unique design, particularly its interaction with the EU ETS and its limited recognition of foreign climate policies, raises complex legal questions, especially concerning compatibility with World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

For US companies engaged in global trade, particularly those sourcing materials from or competing with businesses in major industrial economies like Japan, understanding the intricacies of CBAM is crucial. This article provides a legal analysis of CBAM's structure, objectives, and potential challenges, focusing on its implications for US businesses involved in trade with Japan.

How CBAM Works: Mechanism and Timeline

CBAM operates by requiring importers of specific goods into the EU to account for the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions embedded in those products during their production process outside the EU.

Covered Goods: Initially, CBAM covers imports in sectors deemed most at risk of carbon leakage:

- Cement

- Iron and Steel

- Aluminum

- Fertilizers

- Electricity

- Hydrogen

The scope also includes some precursors and a limited number of downstream products (e.g., screws and bolts made of iron or steel). The EU has indicated plans to expand this list by 2030 to potentially include all sectors currently covered by the EU ETS.

Phased Implementation: CBAM is being rolled out in two main phases:

- Transitional Phase (October 1, 2023 – December 31, 2025): During this period, importers of CBAM goods are primarily subject to reporting obligations. They must submit quarterly reports detailing the volume of imports, their country of origin, the production installation, the production methods used, and, most importantly, the direct and indirect GHG emissions embedded in the goods. No financial payments or purchase of certificates are required during this phase, but failure to report can result in penalties. The goal is data collection and system refinement.

- Definitive Phase (Starting January 1, 2026): From this date, the full financial obligations of CBAM will apply. Importers (or their authorized representatives) must:

- Become "authorized CBAM declarants."

- Annually declare the quantity of CBAM goods imported and their verified embedded emissions for the preceding calendar year (first declaration due by May 31, 2027, for 2026 imports).

- Purchase and surrender a corresponding number of "CBAM certificates" to cover these declared emissions.

Linkage to EU ETS: The price of CBAM certificates is directly tied to the carbon price within the EU ETS. Specifically, it will be calculated based on the weekly average auction price of EU ETS allowances (expressed in €/tonne of CO2 emitted). This direct link is fundamental to CBAM's objective of equalizing the carbon cost between domestic EU production and imports.

Furthermore, the implementation of CBAM is synchronized with the gradual phasing out of free ETS allowances currently allocated to EU industries in the covered sectors. As free allowances decrease within the EU (between 2026 and 2034), the number of CBAM certificates required for corresponding imports will increase proportionally, ensuring a parallel carbon cost exposure.

Calculating the Burden: Embedded Emissions and Carbon Price Adjustments

The core of the CBAM obligation lies in accounting for embedded emissions and potentially adjusting for carbon prices already paid.

Embedded Emissions: This refers to the GHG emissions released during the production process of the imported goods. CBAM covers both:

- Direct Emissions: Emissions from the production process itself, including heating and cooling.

- Indirect Emissions: Emissions from the generation of electricity consumed during the production process. (Reporting of indirect emissions is required during the transition, and their inclusion in the financial obligation from 2026 is planned, subject to methodology development).

Importers must report emissions based on actual verified data from the specific production installations where the goods were made. This necessitates close cooperation with non-EU producers to obtain detailed, verified emissions data according to EU methodologies.

If actual emissions data cannot be adequately determined (e.g., due to lack of cooperation from the producer or insufficient monitoring systems), default values will be used. These default values are generally expected to be based on average emission intensities for similar goods in the exporting country or potentially based on the performance of the least efficient EU installations, creating a strong incentive for non-EU producers to provide actual data. Specific default values apply to electricity imports.

Carbon Price Paid Deduction: Article 9 of the CBAM Regulation allows importers to claim a reduction in the number of CBAM certificates they need to surrender if a "carbon price" has already been effectively paid for the declared embedded emissions in the country of origin. This is intended to prevent "double protection" or charging twice for the same emissions.

However, the definition of an eligible "carbon price" is specific. It currently includes:

- A carbon tax.

- A levy or fee directly linked to GHG emissions.

- The cost of purchasing allowances under a mandatory GHG emissions trading system.

This narrow definition is a potential point of friction, as it may not recognize other forms of climate regulation or mitigation efforts undertaken in exporting countries (e.g., performance standards, subsidies for green technology, renewable energy mandates, certain types of energy taxes not explicitly targeting carbon content) that might have an equivalent effect on reducing emissions or imposing costs on producers.

Rationale and Controversy: Leakage Prevention vs. Trade Impact

The EU justifies CBAM primarily as a necessary measure to prevent carbon leakage and maintain a level playing field for its industries operating under the ETS. The argument is that without CBAM, the carbon costs imposed by the ETS would simply lead to production shifting outside the EU, undermining both the EU's climate goals and its industrial competitiveness.

However, the mechanism's design inherently assumes that the EU ETS price is the appropriate global benchmark for carbon costs. By requiring importers to purchase certificates reflecting this price (minus limited deductions), CBAM effectively seeks to impose the EU's specific carbon pricing standard on goods produced globally.

This approach faces criticism on several fronts:

- Ignoring Policy Diversity: It provides limited recognition for the diverse range of climate policies adopted by other countries. Many nations employ regulatory standards, subsidies, or other measures, rather than explicit carbon taxes or ETS, to achieve emissions reductions. CBAM's narrow definition of "carbon price paid" may fail to credit these potentially equivalent efforts.

- Data Burden and Complexity: Accurately calculating and verifying embedded emissions across complex international supply chains is a significant technical and administrative challenge, particularly for producers in countries with less developed monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems.

- Potential Protectionism: Critics argue that CBAM, despite its stated environmental goals, could function as a disguised trade barrier, protecting EU industries by imposing additional costs and complex requirements on imports. The use of potentially high default values for emissions calculations could exacerbate this effect.

Compatibility with International Trade Law (WTO)

The design of CBAM raises significant questions about its consistency with WTO rules, primarily under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT).

1. Border Measure vs. Internal Regulation (GATT Art. II vs. Art. III): While colloquially termed a "carbon border tax," CBAM is structured to apply after goods have cleared customs, based on their embedded emissions, and is linked to an internal EU measure (the ETS). Most analyses suggest it's more likely to be considered an internal regulation affecting imported goods, falling under GATT Article III (National Treatment), rather than a border tariff violating Article II commitments.

2. National Treatment (GATT Art. III): This principle requires that imported products, once they enter the domestic market, are treated no less favorably than "like" domestic products regarding internal taxes and regulations. Potential issues for CBAM include:

- Are the methodologies for calculating embedded emissions and the associated verification burdens equivalent for imports and domestic products (considering ETS MRV rules)?

- Does the limited recognition of foreign carbon prices effectively lead to less favorable treatment for imports from countries with different but potentially equally effective climate policies?

- Could the application of default values disproportionately burden imports?

3. Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) Treatment (GATT Art. I): This requires treating imports from all WTO members equally. CBAM exempts imports from countries fully participating in or linked to the EU ETS (like EEA countries). While potentially justifiable under GATT Article XXIV (covering customs unions and free trade areas), applying this exemption while not providing equivalent exemptions or recognition for non-ETS countries with ambitious climate policies raises serious MFN concerns.

4. General Exceptions (GATT Art. XX): Even if CBAM were found inconsistent with Articles I or III, the EU could seek to justify it under Article XX, likely paragraphs (b) (protection of human, animal, or plant life or health) or (g) (conservation of exhaustible natural resources). Climate change mitigation arguably fits these categories (viewing the atmosphere's absorption capacity as an exhaustible resource or climate stability as essential for life/health).

However, the main challenge lies in meeting the requirements of the Article XX Chapeau (introductory clause). The Chapeau prohibits measures applied in a manner that constitutes "arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail" or a "disguised restriction on international trade." Key concerns here include:

- Unjustifiable Discrimination: Does imposing the EU's specific ETS price standard and narrowly defined carbon price deduction mechanism on all exporting countries, regardless of their diverse national circumstances and policy choices, constitute unjustifiable discrimination? If a country achieves equivalent emissions reductions through different means, is it justifiable to ignore those efforts?

- Arbitrary Discrimination: Could the procedures for data verification, the application of default values, or the specific exemptions granted be seen as arbitrary?

- Disguised Restriction: Could the overall impact and design of CBAM, despite its environmental aims, effectively function as a disguised restriction on trade, particularly if less trade-restrictive alternatives for achieving the climate goals exist?

Legal analyses suggest that justifying CBAM under the Article XX Chapeau could be difficult, particularly due to the perceived lack of flexibility in recognizing diverse foreign climate efforts and the potential for discriminatory application based on the EU's internal system.

Implications for US Businesses Trading with Japan

The implementation of CBAM creates a complex web of considerations for US companies involved in trade flows connecting to Japan and the EU.

- Direct Exports from Japan to EU: US companies owning subsidiaries in Japan that export CBAM-covered goods directly to the EU will face the full reporting and, from 2026, financial obligations. They will need to implement systems in Japan to track and verify embedded emissions according to EU standards.

- Supply Chain Impacts: US companies sourcing CBAM-covered materials (like steel or aluminum components) from Japan for incorporation into products eventually sold in the EU will be indirectly affected. Their EU importers (potentially the US company's own EU entity or a customer) will need emissions data originating from the Japanese production process. This will necessitate demanding detailed, verifiable emissions information from Japanese suppliers, potentially leading to increased costs or supply chain adjustments if suppliers cannot provide the necessary data.

- Competitive Landscape: CBAM will alter the cost competitiveness of goods entering the EU. US companies exporting similar goods to the EU will need to assess how CBAM impacts their Japanese competitors. If Japan's relevant climate policies are not fully recognized under the "carbon price paid" mechanism, Japanese goods might face higher CBAM costs, potentially improving the relative competitiveness of US goods (assuming the US also lacks a federally recognized carbon price). Conversely, if US production is more carbon-intensive, CBAM could favor imports from Japan if some Japanese carbon pricing is recognized.

- Data Acquisition Challenges: Obtaining accurate, verifiable embedded emissions data from Japanese suppliers, potentially several tiers up the supply chain, will be a significant practical challenge. Companies will need robust supplier engagement strategies and potentially contractual clauses to ensure data flow. Language barriers and differing technical standards could add complexity.

- Uncertainty over Policy Recognition: A key uncertainty is the extent to which Japan's domestic climate policies (e.g., Tokyo's cap-and-trade system, potential future national carbon pricing mechanisms, energy efficiency standards) will qualify for deduction under CBAM's definition of "carbon price paid." Lack of recognition would increase the CBAM burden on Japanese exports.

Navigating CBAM Compliance

For US businesses potentially impacted by CBAM through their Japanese trade links, proactive preparation is essential:

- Map Supply Chains: Identify any supply chains involving the production of CBAM-covered goods in Japan that ultimately enter the EU market.

- Understand Data Requirements: Familiarize yourself with the specific GHG emissions data (direct and indirect) required under CBAM methodologies during the transitional phase.

- Engage Japanese Suppliers: Initiate dialogue with relevant Japanese suppliers about their capacity to monitor, report, and verify embedded emissions according to EU standards. Understand their plans for compliance.

- Assess Data Gaps: Identify potential gaps in data availability and explore solutions, including reliance on default values (understanding the risks) or investing in improved MRV capabilities within the supply chain.

- Model Financial Impact: Estimate the potential cost of CBAM certificates from 2026 based on expected embedded emissions from Japanese sources and current/projected ETS allowance prices. Factor in uncertainties regarding carbon price deductions.

- Monitor Developments: Stay informed about the evolution of CBAM rules (delegated/implementing acts), potential expansions in scope, international reactions, and any relevant WTO proceedings.

Conclusion: A New Dimension in Climate Policy and Trade

The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism marks a significant step in integrating climate policy with trade rules. While aimed at the valid goal of preventing carbon leakage, its design – particularly its reliance on the EU ETS price as a global benchmark and its limited recognition of diverse international climate efforts – creates substantial compliance challenges for global businesses and raises complex questions about fairness and WTO compatibility.

For US companies with ties to Japan, whether through direct exports, sourcing, or competition, CBAM introduces a new layer of complexity. Navigating its requirements demands enhanced supply chain transparency, robust data management, and strategic engagement with Japanese partners. The success and ultimate impact of CBAM will depend not only on its effective implementation but also on ongoing international dialogue and potential adjustments to better accommodate the varied landscape of global climate action. Staying ahead requires understanding the mechanism, anticipating its effects, and preparing for a future where carbon footprints are increasingly factored into the cost of international trade.

- Taxing the Digital Economy: Japan’s New Rules for Platform Taxation

- Japan’s Digital Currency Frontier: Understanding New Stablecoin Regulations and the Future Digital Yen

- EU Battery Regulation: Global Reach—Navigating Its Impact on US and Japanese Supply Chains

- METI — FAQ on EU CBAM for Japanese Exporters (JP)

https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/energy_environment/cbam_faq.html