Estate Division, Unregistered Rights, and Third-Party Claims: A 1971 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling in Modern Context

Date of Judgment: January 26, 1971 (Showa 46)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 45 (o) No. 398 (Claim for Consent to Share Correction Registration Procedure)

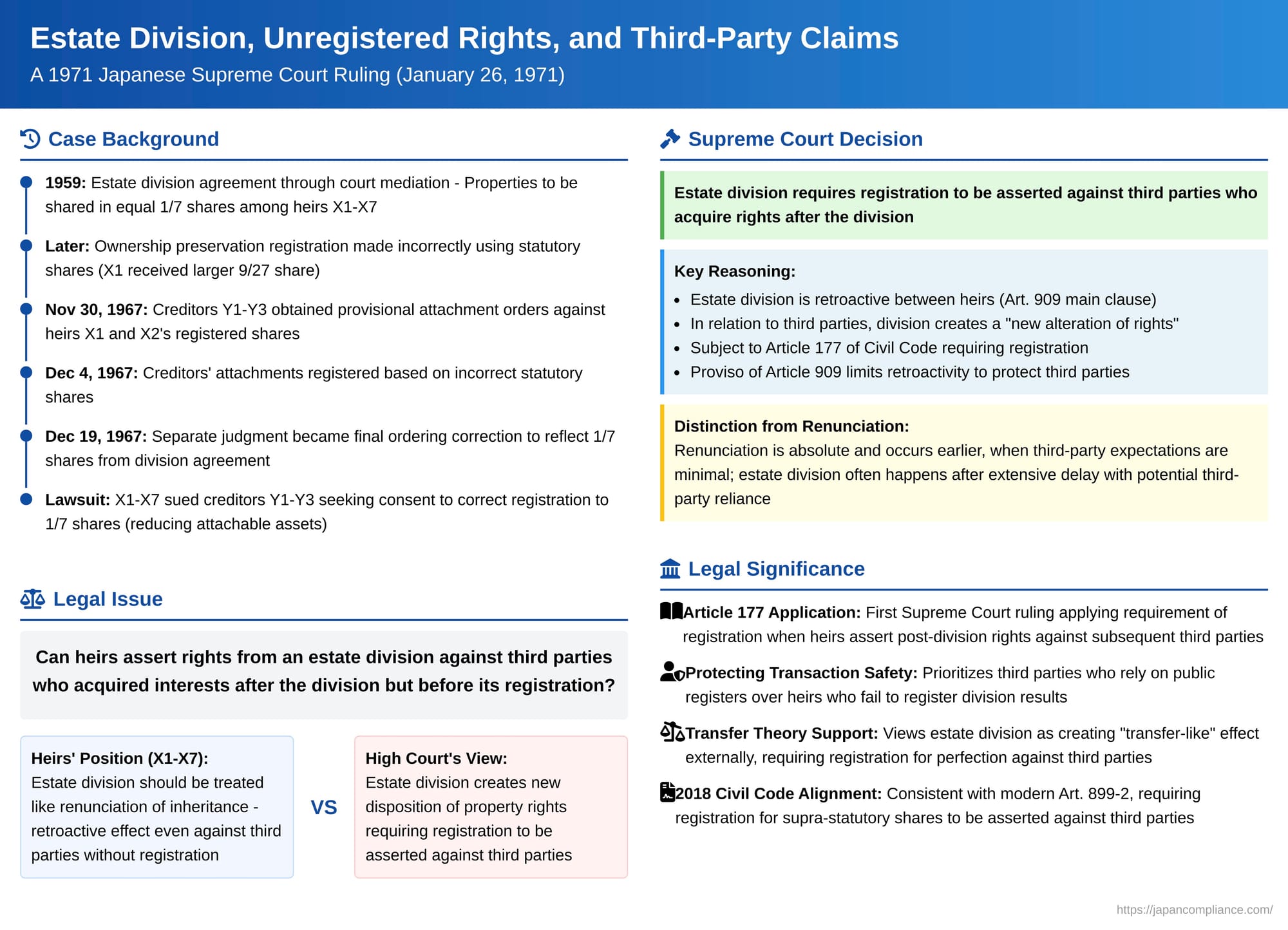

When co-heirs divide an inherited estate, the agreement they reach (遺産分割 - isan bunkatsu) determines the final ownership of specific assets. While this division is legally retroactive to the time of the deceased's death as among the heirs themselves, a critical question arises regarding its effect on third parties who subsequently acquire interests in the inherited property, especially if the results of the estate division have not yet been reflected in the public property register. The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this pivotal issue on January 26, 1971, ruling on the necessity of registration for an heir to assert rights acquired through estate division against such third parties.

Facts of the Case: An Unregistered Division Meets Subsequent Creditor Attachments

The case involved a complex series of events following an inheritance:

- The Deceased and Heirs: A passed away, and an inheritance process commenced. The heirs included A's wife, X1 (Tsuyoko K.), their children X2 through X7, and other relatives B1-B3 and B4 (an heir by representation).

- Estate Division Agreement (1959): In Showa 34 (1959), a formal estate division agreement was reached through court mediation. This agreement stipulated that specific real properties belonging to A's estate—Properties Alpha, Beta, and Gamma—would be acquired by a subset of the heirs, X1 through X7, with each of these seven heirs receiving an equal 1/7 share in these properties. However, despite this agreement, an ownership preservation registration reflecting this specific division was not immediately made.

- Incorrect Subsequent Registration Based on Statutory Shares: Some years later, due to actions initiated by creditors of some of the X-group heirs, an initial ownership preservation registration (所有権保存登記 - shoyūken hozon tōki) was effected for Properties Alpha, Beta, and Gamma. Critically, this registration was not based on the 1/7 shares agreed upon in the 1959 estate division. Instead, it was based on the heirs' statutory inheritance shares (法定相続分 - hōtei sōzokubun). This resulted, for example, in X1 (the wife) being registered with a much larger statutory share (e.g., 9/27 of Properties Alpha and Beta, and 10/30 of Property Gamma), while other heirs (X2 and others, with B4 apparently omitted in one registration) were registered with smaller statutory fractional shares.

- Separate Judgment Ordering Correction of Registration: In a separate lawsuit, a judgment became final and binding on December 19, 1967. This judgment acknowledged the 1959 estate division agreement and ordered that the incorrect statutory share registration be corrected to accurately reflect the 1/7 shares that X1-X7 were entitled to under that agreement.

- Third-Party Creditor Attachments: Here lies the crux of the dispute. On November 30, 1967—just before the judgment ordering the correction of registration became final, and possibly even before it was rendered—Y1, Y2, and Y3 (the defendants/appellees), who were creditors of heirs X1 and X2, obtained provisional attachment orders (仮差押え - karisashiosae) against X1's and X2's shares in the Properties. These attachments were registered on December 4, 1967. Importantly, these attachments were based on the shares as they appeared in the uncorrected statutory share registration—meaning Y1-Y3 attached X1's larger (e.g., 9/27) share and X2's statutory share, not the smaller 1/7 shares they were supposed to have under the (still effectively unregistered) estate division agreement.

- The Current Lawsuit: X1-X7 (the heirs entitled to 1/7 shares each under the 1959 division) then filed the present lawsuit against Y1-Y3 (the attaching creditors). They sought a court order compelling Y1-Y3 to consent to the correction of the property registration to reflect the 1/7 shares determined by the 1959 estate division. If successful, this correction would reduce the registered shares of X1 and X2, thereby diminishing the extent of the assets available to satisfy Y1-Y3's attachments.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the first instance court and the High Court dismissed the claims of X1-X7. The High Court reasoned that an estate division, although having a retroactive effect between the heirs, effectively creates a new disposition of property rights. To assert such changes against third parties who acquire interests in the property after the division agreement but before its registration, registration of the division's outcome is necessary under Article 177 of the Civil Code (which governs the perfection of real rights).

- Appeal by X1-X7 to the Supreme Court: X1-X7 appealed this decision. They argued that the legal effect of an estate division should be treated similarly to that of a renunciation of inheritance (相続の放棄 - sōzoku no hōki), which is generally considered to have an absolute retroactive effect that can be asserted against third parties even without registration.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Registration Matters for Post-Division Third Parties

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1-X7, affirming the High Court's conclusion that registration of the estate division outcome was necessary to prevail against these subsequent attaching creditors.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Estate Division and Article 177 of the Civil Code:

The Court acknowledged that an estate division is retroactive to the time of inheritance as between the co-heirs themselves (Article 909, main clause, Civil Code). However, it held that in relation to third parties, an estate division that results in an heir acquiring rights different from what they initially obtained through statutory inheritance is substantively no different from a new alteration or acquisition of rights occurring at the time of the division agreement.

Therefore, such changes in an heir's co-ownership share of real property resulting from an estate division are subject to Article 177 of the Civil Code. This article requires registration for a change in real property rights to be asserted against third parties.

Consequently, an heir who, through an estate division, acquires rights to a property that differ from (e.g., are greater in a specific asset than) their original statutory inheritance share cannot assert these newly defined rights against a third party who subsequently acquires an interest in that property unless the outcome of the estate division has been duly registered. - Distinction from Renunciation of Inheritance:

The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the appellants' argument that estate division should be treated analogously to renunciation of inheritance.- Limited Retroactivity of Estate Division: Article 909, proviso, of the Civil Code states that an estate division cannot prejudice the rights of third parties. The Court clarified that this proviso primarily protects third parties who acquired interests in the inherited property after the inheritance commenced but before the estate division was finalized. This limitation on the retroactive effect of estate division distinguishes it from renunciation of inheritance, which (according to then-prevailing case law, e.g., Supreme Court Showa 42.1.20) was considered to have an absolute retroactive effect, not generally limited by third-party rights.

- Rationale for the Distinction: The Court explained that the purpose of Article 909 proviso is to protect legal stability, as third parties frequently acquire interests in inherited property during the often-extended period before a formal division is agreed upon or adjudicated. Allowing a later division to retroactively invalidate these intervening third-party rights would be highly disruptive. In contrast, renunciation of inheritance is typically only possible for a short period after the heir becomes aware of the inheritance, and any act of disposition over estate property by the heir generally bars them from renouncing. Therefore, the likelihood of third parties acquiring interests that would be significantly and unexpectedly affected by a later renunciation was considered comparatively lower, justifying a more absolute retroactive effect for renunciation.

- Protecting Third Parties Who Transact After Division but Before its Registration: The Court further reasoned that even after an estate division agreement has been reached among heirs, third parties might still transact based on the appearance of co-ownership according to the pre-division state (e.g., based on statutory shares as reflected in an uncorrected register, or the absence of any specific division registration). The need to protect such third parties, who rely on this appearance, is similar in nature to the need to protect those who acquired interests before the division (who are covered by Article 909 proviso).

- Thus, in relation to third parties who acquire interests after an estate division has occurred but before that division's outcome has been registered, the division should be treated as creating a new change in real property rights. As such, registration is required as a condition for asserting the results of that division against these third parties (a perfection requirement, or 対抗要件 - taikō yōken).

- Scope of "Third Party" in Article 909 Proviso vs. Article 177:

The Court clarified that the "third party" referred to in the proviso of Article 909 specifically means those who acquire interests after the inheritance begins but before the estate division. For third parties who acquire interests after the estate division has been finalized (but before it's registered), the governing provision for asserting rights against them is Article 177 of the Civil Code.

In this case, Y1-Y3 (the attaching creditors) acquired their interest (the provisional attachments) after the 1959 estate division agreement but before that agreement's outcome (the 1/7 shares) was properly reflected in the land register. They relied on the existing (albeit incorrect from the perspective of the 1959 agreement) registration based on statutory shares. Therefore, X1-X7 could not assert their 1/7 shares (which were different from and, for X1, smaller than her registered statutory share) against Y1-Y3 without having registered the division outcome first.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1971 Supreme Court decision is a cornerstone in Japanese law concerning the interplay between inheritance, estate division, and property registration.

- Application of Article 177 to Post-Division Third Parties: This was the first Supreme Court ruling to explicitly apply Article 177 of the Civil Code to the scenario where an heir seeks to assert rights acquired through an estate division (that differ from their statutory share) against a third party who subsequently acquired an interest in the property based on the pre-division (or incorrectly registered) state of title. The attaching creditors were recognized as such third parties.

- "Transfer-like" Effect of Estate Division for Third Parties: The Court's reasoning—that in relation to third parties, an estate division effectively creates a "new alteration of rights"—suggests that while the division may be "declaratory" among the heirs due to its retroactivity, it has a "transfer-like" effect externally. This means it's treated as a new disposition of property interests that requires registration for perfection against subsequent third parties. Legal commentary notes this is consistent with how Japanese law often treats legal acts with retroactive effect when third-party interests are involved.

- Reinforcing the Importance of Registration: The decision underscores the critical role of property registration in protecting rights against third parties. Heirs who benefit from an estate division that allocates them shares different from (particularly greater in specific assets than) their statutory shares must promptly register this outcome to safeguard their newly defined rights against subsequent claimants or acquirers.

- Balancing Interests: The ruling attempts to balance the interests of heirs in finalizing their inheritance with the interests of third parties who rely on the public register (or the apparent state of ownership). It leans towards protecting third parties who transact after the division but before its registration, placing the onus on the heirs to register the results of their division.

- Distinction from Renunciation of Inheritance Maintained: The Court firmly maintained the distinction between the legal effects of estate division and renunciation of inheritance, particularly concerning their retroactivity and impact on third-party rights.

- The 2018 Civil Code Amendment (Article 899-2) and its Interplay: It's crucial to consider this 1971 ruling in light of the 2018 amendment to the Civil Code, which introduced Article 899-2.

- This new article stipulates that if an heir acquires rights through inheritance (including by will or specific share designation) that exceed their statutory inheritance share, they cannot assert these rights exceeding their statutory share against a bona fide third party unless those rights are registered.

- Legal commentary indicates that the fundamental conclusion of the 1971 Supreme Court judgment—that registration is necessary to assert rights acquired through an estate division that differ from statutory shares against subsequent third parties—is maintained and consistent with the principles underlying Article 899-2. Estate division is a primary way an heir might acquire rights to specific assets that differ from a simple pro-rata statutory share of all assets.

- Article 899-2 now provides a direct statutory basis for requiring registration for supra-statutory shares obtained through various inheritance mechanisms, including, by implication, estate division agreements that reallocate statutory entitlements.

- Conversely, Article 899-2 also implies that an heir can assert their rights up to their statutory inheritance share against a third party without registration. This aspect aligns with earlier Supreme Court rulings (e.g., Showa 38.2.22) that allowed heirs to protect their basic statutory share even if unregistered, against those claiming under another co-heir's defective title.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1971 decision was a pivotal judgment clarifying that heirs who acquire rights to real property through an estate division that differ from their original statutory inheritance shares must register this new allocation to protect their rights against third parties who subsequently acquire interests in the property. By applying Article 177 of the Civil Code to this scenario, the Court prioritized the stability of transactions and the role of the property register in mediating conflicts between heirs and subsequent third-party claimants. This principle, now reinforced by the spirit and provisions of the 2018 Civil Code amendments (specifically Article 899-2), continues to underscore the importance of timely and accurate registration following an estate division in Japan.