Estate Division Agreements and Creditor Rights: Can They Be Undone as Fraudulent Acts?

Date of Judgment: June 11, 1999 (Heisei 11)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Heisei 10 (o) No. 1077 (Claim for Loan Repayment and Avoidance of Fraudulent Act)

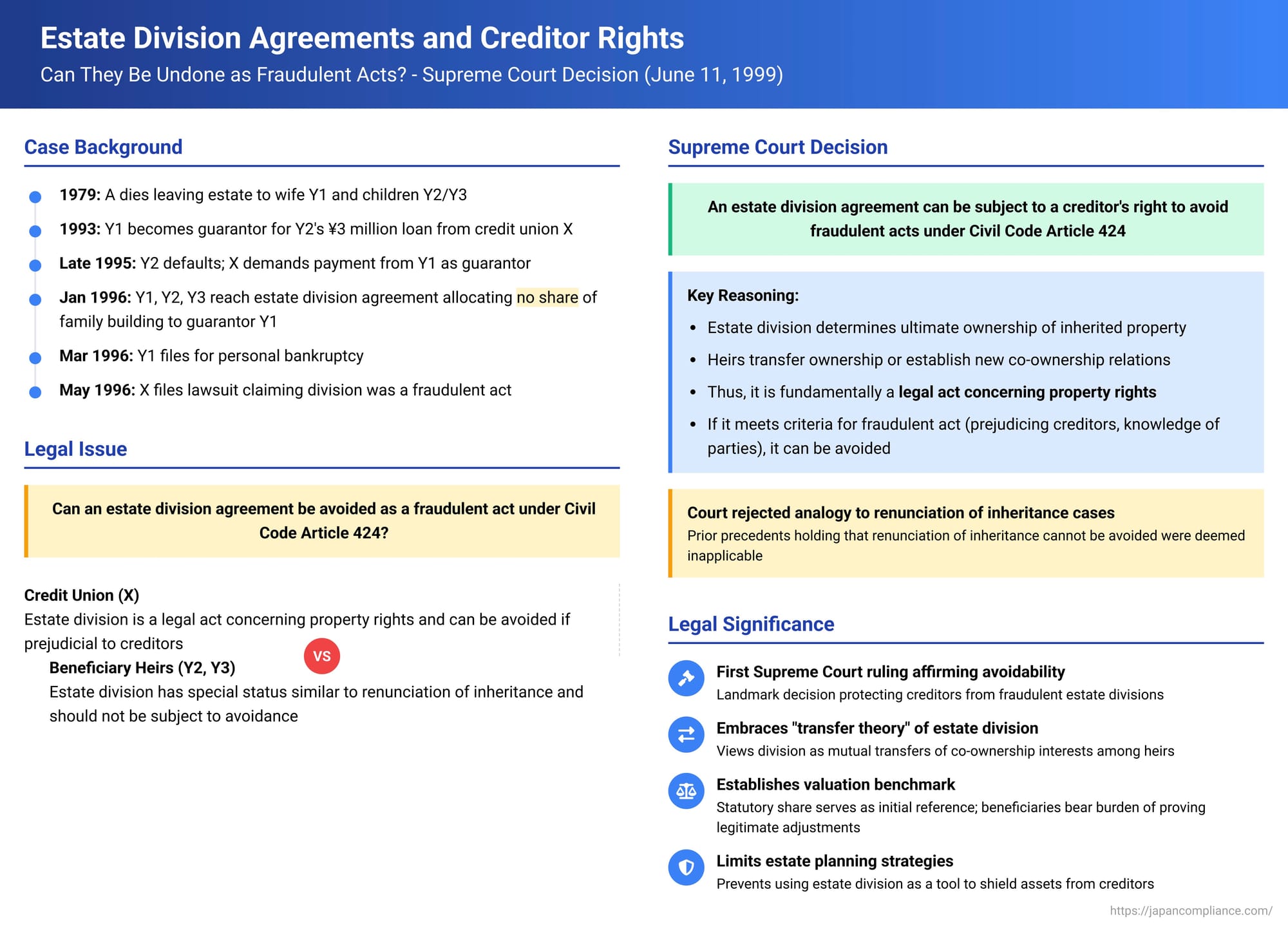

When co-heirs divide an inherited estate, they often reach an agreement (遺産分割協議 - isan bunkatsu kyōgi) that allocates specific assets to each heir. But what if one of the heirs is indebted, and the estate division agreement results in that heir receiving a significantly smaller share of the estate than they would otherwise be entitled to, or even no share at all in valuable assets? Can that heir's creditors step in and challenge the agreement as a "fraudulent act" (詐害行為 - sagaikōi) designed to improperly shield assets? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this critical intersection of inheritance law and creditor protection in its decision on June 11, 1999.

Facts of the Case: An Estate Divided Amidst Mounting Debt

The case involved the estate of A, who passed away on February 24, 1979.

- The Heirs and Key Asset: A's legal heirs were his wife, Y1, and their two children, Y2 and Y3 (the appellants in the Supreme Court). A key asset in the estate was a building situated on leased land, where Y1 resided. Y2 and Y3 had married and were living elsewhere.

- Y1's Guarantee Obligation: Years later, in October 1993, Y1 undertook a significant financial obligation. She became a joint and several guarantor for a ¥3 million loan that X, a credit union (the plaintiff/appellee), extended to Y2 (her child) and another individual.

- Default and Creditor's Demand: The primary debtors, including Y2, subsequently defaulted on the loan. As a result, X Credit Union turned to Y1, demanding that she fulfill her obligations under the joint and several guarantee. X also requested that Y1 take steps to complete the inheritance registration for the building (which was still formally registered in the deceased A's name) to reflect her inherited share, which X presumably viewed as an asset to satisfy the guarantee debt.

- The Disputed Estate Division Agreement: Following X's demand, around January 5, 1996, a crucial event occurred. Y1, Y2, and Y3 entered into an estate division agreement concerning A's estate. The most significant term of this agreement was that Y1, the debtor-guarantor, would receive no share whatsoever in the family building. Instead, the agreement stipulated that Y2 and Y3 would each acquire a 1/2 co-ownership share of the building. They promptly completed the ownership transfer registration reflecting this division on the same day.

- Y1's Bankruptcy: Despite having previously suggested to an employee of X Credit Union that she intended to repay her guarantee obligation in installments over an extended period, Y1 filed for personal bankruptcy on March 21, 1996, shortly after the estate division agreement was concluded and registered.

- X Credit Union's Lawsuit: On May 29, 1996, X Credit Union initiated a lawsuit. In addition to seeking repayment of the outstanding loan from the primary debtors and Y1, X also specifically targeted the estate division agreement. X claimed that this agreement was a fraudulent act designed to remove Y1's share of the building from the reach of her creditors (chiefly X). X sought the court's intervention to:

- Avoid (cancel) the estate division agreement.

- Order Y2 and Y3 to re-register the building to reflect Y1 holding an inheritable share. (X initially claimed Y1 should have a 1/3 statutory share, but later adjusted its claim, effectively asking that Y1 be attributed a share that X could then legally pursue to satisfy its claim – the specifics of the share adjustment appear to aim for a 1/3 interest for Y1).

- Lower Court Rulings in Favor of X: Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled in favor of X Credit Union, finding that the estate division agreement could indeed be subject to avoidance as a fraudulent act. The High Court elaborated that while an estate division resulting in an unequal distribution might sometimes be justified by specific circumstances (such as the terms of a will, recognition of an heir's special contributions to the estate, or accounting for substantial lifetime gifts received by an heir), Y2 and Y3 had failed to prove any such justifying factors in this case. Therefore, the agreement, which effectively transferred Y1's presumptive share to Y2 and Y3 for no consideration while Y1 was indebted to X, was deemed a fraudulent act.

- Appeal by Y2 and Y3: Y2 and Y3, the beneficiaries of the estate division agreement, appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Estate Division Agreements Are Not Immune

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y2 and Y3, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions.

The Court laid down a clear and significant principle:

An estate division agreement concluded among co-heirs can be subject to the exercise of a creditor's right to avoid (cancel) fraudulent acts under Article 424 of the Civil Code.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- An estate division agreement fundamentally serves to determine the ultimate ownership of inherited property. Upon the death of the deceased, this property becomes co-owned by the co-heirs.

- The agreement achieves the final allocation of this property either by transferring full ownership of specific assets to individual heirs or by establishing new co-ownership relationships among them for particular assets.

- Therefore, by its very nature, an estate division agreement is a legal act concerning property rights (財産権を目的とする法律行為 - zaisanken o mokuteki to suru hōritsu kōi).

- As such, if an estate division agreement meets the general criteria for a fraudulent act (i.e., it is an act concerning property, it prejudices the debtor's creditors, and the debtor and potentially the beneficiaries had the requisite knowledge or intent), it can be subject to avoidance by a prejudiced creditor.

The Supreme Court also briefly addressed the appellants' argument that this case should be treated similarly to "renunciation of inheritance" (相続の放棄 - sōzoku no hōki). Prior Supreme Court precedents had established that a renunciation of inheritance is not subject to fraudulent act avoidance. The Court summarily stated that these precedents dealt with different factual scenarios and were not applicable to the case of an estate division agreement.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1999 Supreme Court judgment was a landmark decision with several important implications for inheritance law and creditor rights in Japan:

- First Supreme Court Affirmation of Avoidability: This was the first time the Supreme Court explicitly held that an estate division agreement can be challenged and potentially nullified by a creditor as a fraudulent act. This provided crucial protection for creditors of heirs who might otherwise use an estate division to improperly shield assets.

- Underlying View of Estate Division – The "Transfer Theory" (Iten-shugi): The Supreme Court's characterization of an estate division agreement as a process that "determines the attribution of inherited property...by making all or part of it the sole property of each heir, or by transitioning it to a new co-ownership relationship" aligns with what legal commentators call the "transfer theory" of estate division. This theory views the division as a series of mutual transfers of co-ownership interests among the heirs to arrive at the final allocation. From this perspective, if an heir agrees to take substantially less than their presumptive (e.g., statutory) share, they are effectively "transferring" or "disposing of" a portion of their property rights, an act which can prejudice their creditors if the heir is insolvent.

- Contrast with the "Declaratory Theory" (Sengen-shugi) and Retroactivity: An alternative view, the "declaratory theory," suggests that an estate division merely "declares" or confirms the specific assets that each heir was entitled to from the moment of the deceased's death. Under a strict application of this theory, it might be harder to argue that an heir is "disposing" of property. However, while estate division has a retroactive effect to the time of death (Article 909, main clause, Civil Code), this retroactivity is explicitly limited by a proviso in Article 909 stating that it cannot prejudice the rights of third parties. Legal commentary suggests that in relation to an heir's creditors (who are third parties), the "transfer theory" is more appropriate, and the retroactive effect of division should not bar a creditor's right to challenge a fraudulent division.

- Distinction from Renunciation of Inheritance: The Court's brief dismissal of the analogy to renunciation of inheritance is significant. Renunciation of inheritance also has a retroactive effect (Article 939, Civil Code), but prior Supreme Court rulings (e.g., Showa 42.1.20 - January 20, 1967) have held this retroactivity to be "absolute" and effective against all third parties, even without registration. Renunciation is often viewed as a passive refusal to accept an increase in one's assets, rather than an active disposition of property already acquired. The different treatment reflects underlying policy considerations, balancing an heir's freedom to renounce an inheritance against the need to protect creditors in cases of active dispositions through estate division agreements.

- Effect of a Successful Avoidance Action:

- At the time of this 1999 judgment (and before the 2017 amendments to the Civil Code concerning fraudulent acts), the avoidance of a fraudulent act generally had a "relative effect." This meant the avoidance was primarily effective between the avoiding creditor (X) and the beneficiaries of the fraudulent act (Y2 and Y3). The estate division agreement itself would technically remain valid as among the co-heirs (Y1, Y2, and Y3). The 2017 Civil Code amendments have since broadened the effect of avoidance, stipulating that it also affects the debtor (Y1).

- In practice, a successful avoidance action would typically result in the portion of the property that Y1 improperly "gave up" being notionally restored to her assets, making it available for X's claim. This might involve Y2 and Y3 having to re-transfer a portion of their shares back to Y1, or paying monetary compensation.

- Scope of Creditors Entitled to Avoid:

- In this specific case, X Credit Union became a creditor of Y1 after A's death (when the inheritance commenced and Y1 notionally acquired her share) but before the disputed estate division agreement was made. This timing gave X a reasonable expectation that Y1's statutory share in A's estate would form part of Y1's assets available to satisfy the guarantee.

- The PDF commentary discusses the broader scope. Creditors whose claims against an heir arose before the inheritance might also be able to avoid a prejudicial estate division, provided their claim pre-dates the estate division agreement itself (as per Article 424, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Code).

- The commentary also briefly touches upon "estate creditors" (creditors of the deceased A). If an estate division leaves an heir (who is also liable for A's debts) with insufficient assets from A's estate to cover their share of those debts, A's creditors might also have grounds to challenge the division as prejudicial.

- Valuation Basis: Statutory Share vs. "Specific/Concrete" Inheritance Share:

A crucial question when determining if an estate division is prejudicial to creditors is what baseline share the debtor-heir was entitled to. Should this be their straightforward statutory inheritance share (法定相続分 - hōtei sōzokubun), or their "specific/concrete" inheritance share (具体的相続分 - gutaiteki sōzokubun)? The specific/concrete share takes into account factors like lifetime gifts the heir may have received from the deceased (special benefits) or contributions the heir may have made to the deceased's estate.- The PDF commentary notes that the majority academic view favors using the specific/concrete inheritance share as the benchmark.

- However, in the present case, the High Court appeared to use Y1's statutory share as the reference because Y2 and Y3 (the beneficiaries) did not provide sufficient evidence of factors (like special benefits received by Y1, or contributions made by Y2/Y3) that would have altered Y1's statutory share. This suggests a practical approach where the statutory share serves as an initial benchmark, and the burden falls on the beneficiaries of the challenged division to prove circumstances that would legitimately reduce the debtor-heir's actual entitlement. Some commentators also argue that from the perspective of an heir's external creditors, the easily ascertainable statutory share should be the primary standard for assessing prejudice, with any internal adjustments among heirs based on specific shares being a secondary matter.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1999 decision is a vital affirmation of creditor protection in the context of inheritance. It establishes that estate division agreements, despite their connection to the deeply personal realm of family succession, are not sacrosanct when they operate to unfairly prejudice the legitimate claims of an heir's creditors. By confirming that such agreements are "legal acts concerning property rights" and thus subject to avoidance as fraudulent acts, the Court has provided an important tool for creditors to prevent heirs from using the estate division process to improperly deplete their assets. This ruling underscores the principle that while heirs have considerable freedom in how they divide an estate, this freedom is not absolute and must yield to the overriding principles of creditor protection when exercised in a manner that constitutes a fraudulent act.