Estate Debts and Reserved Portions: A Japanese Supreme Court Clarification

Decision Date: November 26, 1996

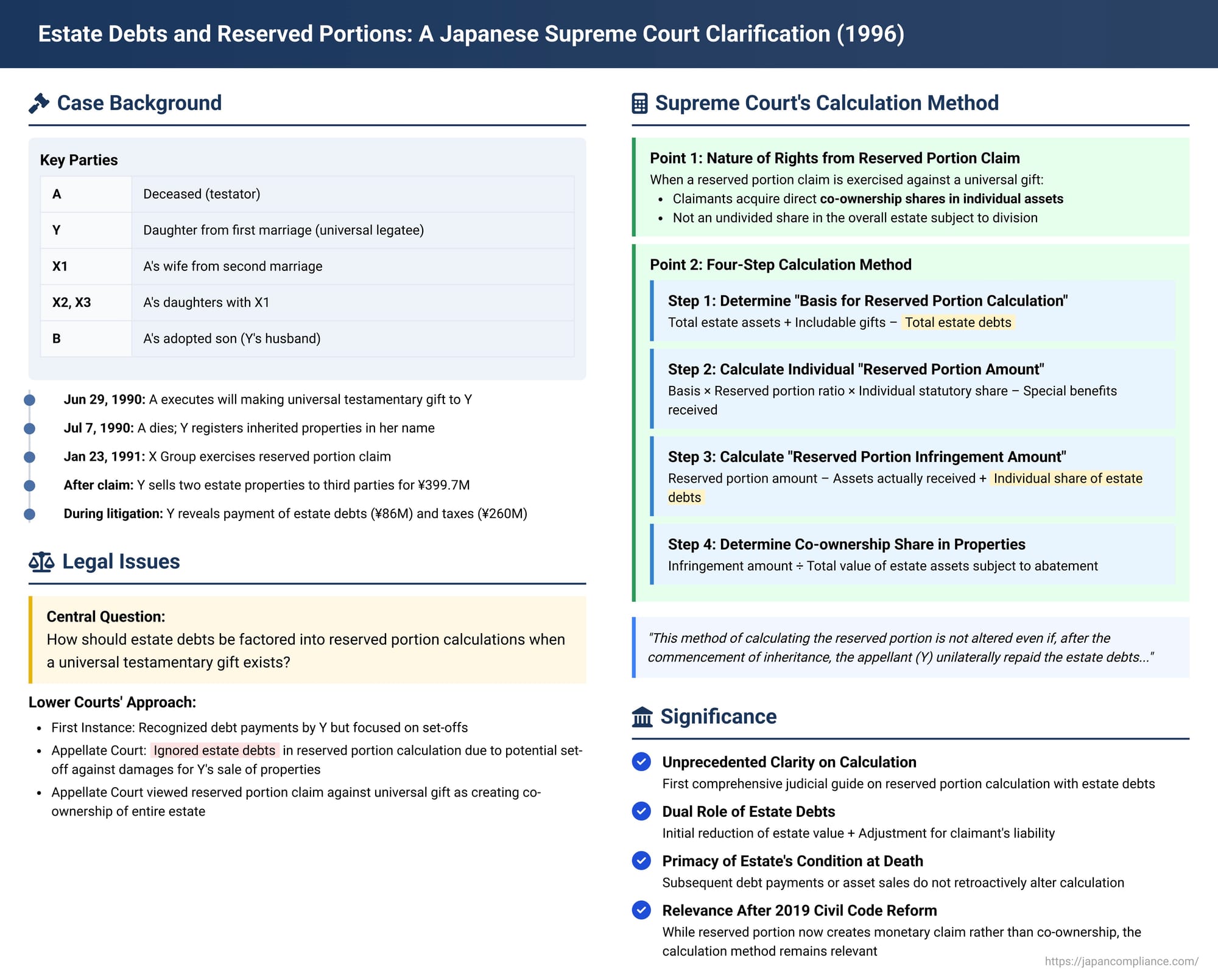

In a pivotal decision handed down on November 26, 1996, Japan's Supreme Court provided crucial guidance on how estate debts are to be factored into the calculation of the legally reserved portion of an inheritance (遺留分, iryūbun) and the subsequent determination of any infringement upon that portion. This case meticulously outlined a methodology that has since been foundational in understanding these complex calculations, particularly when a universal testamentary gift (a gift of the entirety of an estate) is involved.

I. The Factual Background: A Universal Gift and Subsequent Claims

The case centered around the estate of A, who passed away on July 7, 1990. Eight days prior to his death, on June 29, 1990, A had executed a notarized will making a "universal testamentary gift" (全部包括遺贈, zenbu hōkatsu izō) of all his assets to Y, his daughter from a previous marriage.

The legal heirs of A were five individuals:

- X1: A's wife (second marriage).

- X2: A's daughter with X1.

- X3: A's daughter with X1.

- Y: A's daughter from his first marriage, the recipient of the universal gift.

- B: A's adopted son, who was also Y's husband.

Collectively, X1, X2, and X3 (referred to as the "X Group") were entitled to a legally reserved portion of A's estate. Following A's death, Y proceeded to register some of the inherited real estate (Properties 1-29) in her own name.

On January 23, 1991, the X Group formally exercised their reserved portion claim (遺留分減殺請求権, iryūbun gensai seikyūken) against Y. They subsequently filed a lawsuit seeking:

- Confirmation that, due to their reserved portion claim, they had acquired co-ownership shares in all the real properties bequeathed to Y (Properties 1-29). The claimed shares were 1/4 for X1, and 1/16 each for X2 and X3.

- An order compelling Y to complete the registration of transfer for these co-ownership shares for those properties Y had already registered in her sole name (specifically, Properties 2, 5-8, 28, and 29).

During the litigation, it was also revealed that Y, after receiving the reserved portion claim from the X Group, had sold two other estate properties (the "Sold Properties") to third parties for a total of approximately ¥399.7 million without the X Group's consent, and completed the ownership transfer registrations for these sales.

II. The Litigation Journey: Lower Courts Grapple with Debts and Set-Offs

A. First Instance Court

In the initial trial, Y raised several defenses against the X Group's claims:

- She had paid approximately ¥86 million in estate debts.

- She had borne approximately ¥260 million in inheritance taxes.

- The X Group had already received certain estate assets (around ¥16 million in bank deposits from a dissolved account, plus a car).

The X Group countered, arguing:

- Y's sale of the Sold Properties post-claim infringed their co-ownership rights, giving rise to a damages claim against Y. They sought to offset this damages claim (which they valued highly based on the sale price) against any reimbursement Y might claim for paying estate debts.

- Other assets existed in the estate (e.g., further bank deposits, investment subscription rights, land sale receivables).

The first instance court largely ruled in favor of the X Group. It acknowledged Y's payment of estate debts and the X Group's receipt of some assets but found that any reimbursement Y was entitled to from the X Group did not exceed the damages Y owed them for selling the Sold Properties. The court deemed the inheritance tax payment by Y not to be a valid factor for reducing the basis of the reserved portion.

B. Appellate Court

Y appealed. The appellate court upheld the first instance decision, affirming the X Group's claims. Key aspects of its reasoning included:

- Damages and Set-Off: It agreed that Y's sale of the Sold Properties caused a loss of the X Group's co-ownership shares, entitling them to damages from Y. The court noted the X Group's intention to set off this damages claim against Y's claim for reimbursement for her payment of estate debts. The appellate court calculated that Y's reimbursement claim against the X Group for their share of the estate debts (based on the X Group's combined 3/8 statutory inheritance share of the ~¥86 million in debts, amounting to ~¥32 million) was clearly less than the X Group's damages claim against Y (their 3/8 share of the ~¥399.7 million sale proceeds, amounting to ~¥150 million).

- Ignoring Estate Debts in Calculation: Consequently, the appellate court concluded that Y's reimbursement claim for debt payments was extinguished by this set-off. Therefore, the estate debts asserted by Y could be disregarded when calculating the reserved portion. It stated that the X Group acquired their respective shares (1/4 for X1, 1/16 each for X2, X3) in Properties 1-29 without needing to determine the existence, scope, or value of estate debts or the precise scope and value of estate assets at the time of death.

- Nature of Rights: The appellate court also reasoned that the exercise of a reserved portion claim against a universal testamentary gift results in the claimants obtaining a share in the entirety of the estate assets, which then becomes subject to co-ownership among the heirs (akin to an undivided estate).

Y further appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that the determination of estate debts was essential for calculating the reserved portion.

III. The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court overturned the appellate court's decision and remanded the case for retrial. Its judgment addressed two critical legal points:

A. Point 1: Nature of Rights Acquired Through a Reserved Portion Claim

The Supreme Court first clarified the nature of the rights acquired by the X Group. It affirmed, citing its own precedent (Supreme Court, January 26, 1996, Minshu Vol. 50, No. 1, p. 132), that when a reserved portion claim is exercised against a universal testamentary gift:

- The testamentary gift loses its effect to the extent it infringes upon the reserved portion.

- The rights acquired by the legatee (Y) automatically revert to the reserved portion claimants (X Group) to the extent of the infringement.

- Crucially, the rights that revert to the reserved portion claimants in such a scenario are not in the nature of an undivided share in the overall "相続財産" (inherited property subject to estate division). Instead, the claimants acquire direct co-ownership shares in the individual assets comprising the estate.

Therefore, the X Group could legitimately seek confirmation of their specific co-ownership shares in Properties 1-29 and demand registration of those shares. The appellate court's view that it created a co-ownership of the estate as a whole subject to division was implicitly corrected.

B. Point 2: The Correct Method for Calculating Reserved Portion and Infringement Amount When Estate Debts Exist

This was the core of the Supreme Court's ruling and where it found significant fault with the appellate court's approach. The Court meticulously laid out the proper methodology:

Step 1: Determine the "Basis for Reserved Portion Calculation" (遺留分算定の基礎となる財産額)

The calculation must start by establishing the foundational value against which the reserved portion is determined. This involves:

- Taking the total value of all assets the deceased (A) owned at the time of death.

- Adding the value of any gifts made by the deceased that are subject to inclusion under reserved portion rules (Civil Code Arts. 1029, 1030, 1044 – these articles refer to the rules for adding certain lifetime gifts to the calculation base).

- From this sum, subtracting the total amount of the deceased's debts.

This net figure is the "basis for reserved portion calculation."

Step 2: Calculate the Individual Claimant's "Reserved Portion Amount" (遺留分の額)

Once the basis is established, each claimant's individual reserved portion amount is calculated as follows:

- Multiply the "basis for reserved portion calculation" (from Step 1) by the general reserved portion ratio stipulated in Civil Code Art. 1028 (e.g., 1/2 for descendants and spouse).

- If there are multiple reserved portion claimants, this aggregate reserved portion is then multiplied by each claimant's respective statutory inheritance fraction (法定相続分, hōtei sōzokubun).

- If a claimant has received "special benefits" (特別受益財産, tokubetsu jueki zaisan – essentially advancements on their inheritance), the value of such benefits is subtracted from their share.

The result is the claimant's individual "reserved portion amount."

Step 3: Calculate the "Reserved Portion Infringement Amount" (遺留分の侵害額)

This step determines the actual value by which the claimant's reserved portion has been diminished:

- Take the claimant's "reserved portion amount" (from Step 2).

- Subtract the value of any assets the claimant actually inherited or received from the estate directly (if any).

- Add the amount of any estate debts that the claimant is personally responsible for bearing.

This final sum is the "reserved portion infringement amount" – the net value the claimant is entitled to recover.

Step 4: Determine the Co-Ownership Share in Specific Properties

The X Group claimed co-ownership shares in specific properties. The Supreme Court stated that the share they would acquire in Properties 1-29 is determined by:

- Dividing the "reserved portion infringement amount" (calculated in Step 3) by the total value of all A's estate assets subject to abatement, valued as of the time of inheritance commencement (A's death).

C. The Immutability of the Calculation Method

Critically, the Supreme Court emphasized:

"This method of calculating the reserved portion is not altered even if, after the commencement of inheritance, the appellant (Y) unilaterally repaid the相続債務 (estate debts) and extinguished them, nor is it altered if, as a result of this, a right to reimbursement that the appellant (Y) came to have against the appellees (X Group) and a claim for damages that the appellees (X Group) have against the appellant (Y) were offset, resulting in the complete extinguishment of said right to reimbursement."

D. Appellate Court's Fundamental Error

The Supreme Court found that the appellate court's decision to ignore estate debts in the reserved portion calculation was a serious error. The appellate court had effectively allowed the outcome of a later set-off (between Y's claim for reimbursement for debt payment and the X Group's damages claim for Y's sale of assets) to improperly influence the primary calculation of the reserved portion. By failing to determine the existence, scope, and value of estate debts, as well as the scope and value of estate assets at the time of A's death, the appellate court had misapplied the law. This error clearly affected the outcome of the judgment.

The case was therefore remanded to the Osaka High Court for a retrial, where the calculations would have to be redone according to the Supreme Court's prescribed methodology.

IV. Analysis and Lasting Significance

This 1996 Supreme Court decision was a landmark for several reasons:

A. Unprecedented Clarity on Calculation

Prior to this ruling, while the Civil Code established the concept of the reserved portion, it did not explicitly detail the precise sequence of calculations needed to arrive at the "infringement amount," especially when estate debts were involved. This judgment provided the first comprehensive, step-by-step judicial guidance on this complex issue, bringing much-needed clarity and consistency to the field. The method outlined was generally supported and became a key reference point.

B. Correctly Situating Estate Debts in the Calculation

The decision correctly established the dual role of estate debts:

- Initial Reduction of Estate Value: Debts are first deducted from the gross assets to arrive at the net estate value which forms the "basis for reserved portion calculation." This ensures that the reserved portion is a share of the deceased's actual net worth.

- Adjustment for Claimant's Liability: The claimant's own share of responsibility for these debts is then added back when calculating the specific "infringement amount" they are entitled to recover. This is logical because if a claimant is still liable for their share of debts, or if the legatee has paid those debts and has a right to reimbursement from the claimant, the reserved portion claim must account for this to ensure the claimant receives their true net entitlement.

C. Primacy of Estate's Condition at Death

The ruling firmly establishes that the calculation of the reserved portion and any infringement is based on the state of the estate (assets and debts) at the time of the testator's death. Subsequent actions by the legatee, such as paying off debts or selling estate assets, do not retroactively alter this foundational calculation. While such actions might give rise to new, separate legal claims (e.g., a legatee's right to reimbursement from other heirs for debt payments, or heirs' claims for damages against a legatee for improper disposal of assets), these are to be resolved separately or through set-off after the reserved portion infringement has been correctly calculated based on the initial estate values.

D. Nature of Rights (Pre-2018 Reforms)

The Court's confirmation that a successful reserved portion claim against a universal gift (under the law at the time) resulted in direct co-ownership of individual assets was significant. It meant claimants didn't just get a monetary claim or a right to demand a share in a subsequent, lengthy estate division process (遺産分割, isan bunkatsu), but an immediate proprietary interest in the assets themselves.

E. Relevance in Light of 2018 Civil Code Reforms

It's important to note that Japan's Civil Code underwent significant reforms related to inheritance law in 2018 (effective from 2019). A major change was that the exercise of a reserved portion claim no longer results in the automatic reversion of property rights or the creation of co-ownership. Instead, it now gives rise to a monetary claim against the recipient of the infringing gift or bequest for an amount equivalent to the reserved portion infringement (New Civil Code Art. 1046(1)).

- Impact on Point 1 (Nature of Rights): Due to this fundamental shift, the Supreme Court's finding in this 1996 case regarding the creation of co-ownership in individual assets (判旨I) has lost its direct precedential value for claims arising under the new law.

- Enduring Relevance of Point 2 (Calculation Methodology): However, the core principles articulated by the Supreme Court concerning the method of calculating the value of the reserved portion infringement (判旨II① – particularly the steps for determining the "basis for reserved portion calculation" and the "reserved portion amount") are still considered highly relevant. Even though the claim is now monetary, the method for determining the value of that monetary claim—which involves properly accounting for assets, gifts, and crucially, estate debts—is likely to continue to draw upon the logic established in this 1996 decision. The Supreme Court's guidance on how to fairly assess the net estate subject to reserved portion rights remains a vital contribution.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 26, 1996, judgment stands as a critical exposition on the intricacies of Japan's reserved portion system. By meticulously detailing how estate debts must be incorporated into the calculation of reserved portion infringement, the Court provided an enduring framework for ensuring that such claims are adjudicated fairly and accurately, based on the true net value of the deceased's estate at the time of death. While subsequent legal reforms have altered the nature of the remedy, the foundational principles for valuing the infringement, especially the proper accounting of debts, continue to resonate.