Essential Guide to Patent Licensing Agreements in Japan: Key Considerations for US Tech Companies

TL;DR

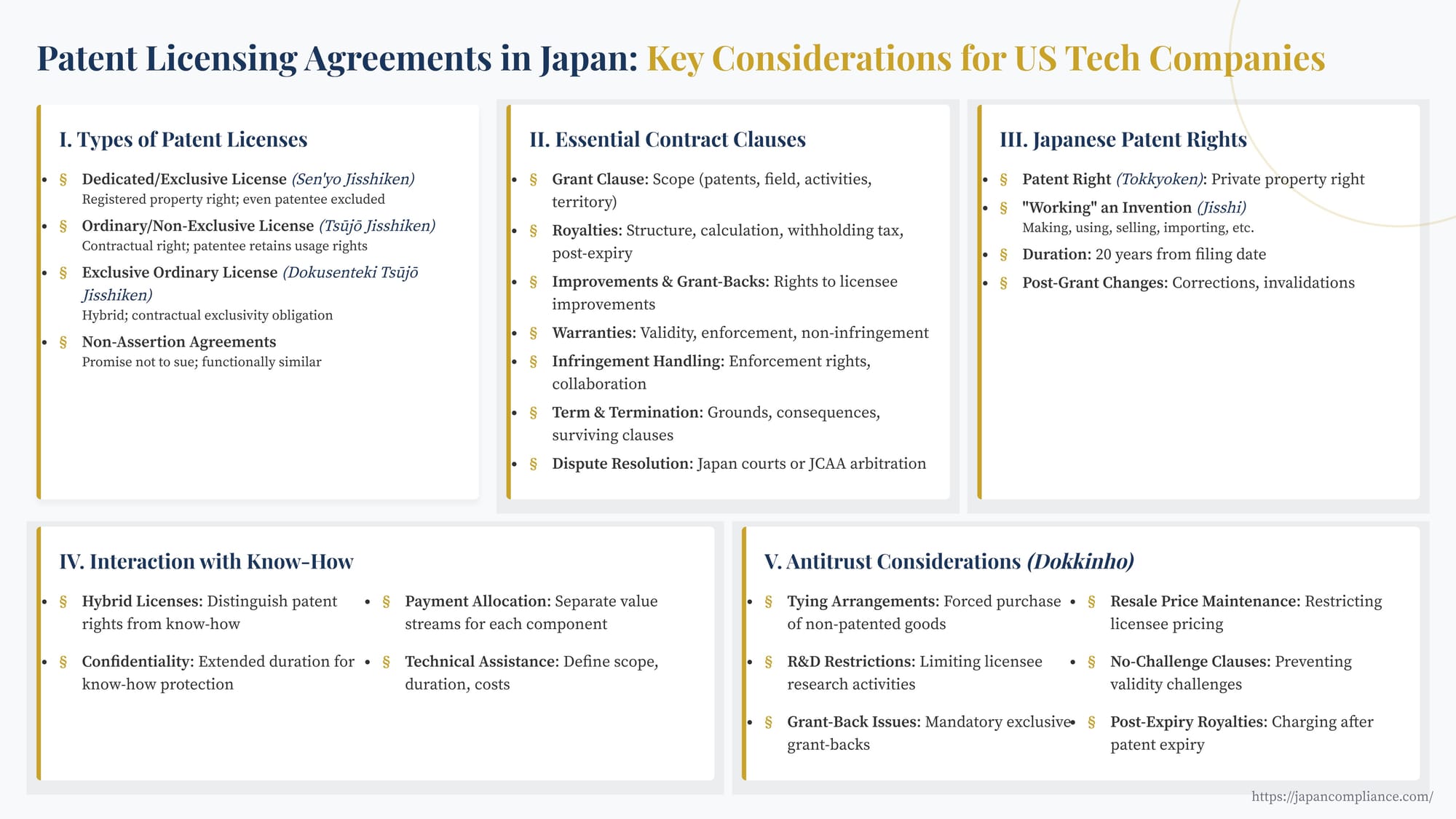

US tech firms licensing patents in Japan must grasp (1) the legal split between exclusive (sen'yo) and ordinary (tsūjō) license rights, (2) antitrust limits on royalties, exclusivity and grant-backs under the Antimonopoly Act, and (3) contract drafting points—scope, sublicensing, tax, and post-expiry payments—so agreements remain enforceable and compliant.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Japanese Patent Rights: The Foundation

- Types of Patent Licenses in Japan

- Key Clauses & Negotiation Points for US Licensors/Licensees

- Interaction with Know-How and Technical Assistance

- Antitrust Considerations: The Antimonopoly Act (Dokkinho)

- Conclusion: Charting a Course for Successful Licensing

For technology companies looking to enter or expand in the Japanese market, patent licensing is often a cornerstone of business strategy. Whether licensing-in core technology from a Japanese partner or licensing-out proprietary innovations, navigating the intricacies of Japanese patent law and contract practices is crucial for success. While sharing fundamental principles with US licensing, the Japanese system has unique characteristics, terminology, and regulatory considerations, particularly concerning antitrust law, that demand careful attention.

This guide provides an overview of key considerations for US businesses when negotiating and drafting patent license agreements under Japanese law. It explores the nature of Japanese patent rights, types of licenses, critical contract clauses, the interplay with know-how, and potential antitrust pitfalls.

Understanding Japanese Patent Rights: The Foundation

Before diving into licensing, it's helpful to grasp some basics of the Japanese patent system:

- Patent Right vs. Patent: In Japanese terminology, a distinction is sometimes drawn between the "patent" (tokkyo) as the administrative grant and the "patent right" (tokkyoken) as the private property right established upon registration (Patent Act, Article 66). This right grants the patentee the exclusive right to commercially work the patented invention (Patent Act, Article 68).

- Scope of "Working" (実施, Jisshi): The definition of "working" a patented invention is broad and specified in the Patent Act (Article 2(3)). For an invention of a product, it includes manufacturing, using, assigning/leasing (assigning, etc.), exporting, importing, or offering for assignment, etc. For a process invention, it includes using the process. For an invention of a process for manufacturing a product, it includes using the process, plus using, assigning, etc., exporting, importing, or offering for assignment, etc., the product manufactured by that process.

- Duration: The patent right generally lasts for 20 years from the filing date of the patent application (Patent Act, Article 67).

- Post-Grant Changes: Unlike copyrights, Japanese patent rights can change after grant. The scope can be narrowed through correction trials (teisei shinpan) or requests for correction within invalidation trial proceedings. Furthermore, a patent can be invalidated ab initio (from the beginning) if an invalidation trial (mukou shinpan) is successful (Patent Act, Article 125). These possibilities necessitate specific considerations in licensing agreements.

Types of Patent Licenses in Japan

Japanese patent law primarily recognizes two main types of licenses granted by the patentee, along with related contractual arrangements:

- Dedicated/Exclusive License (専用実施権, Sen'yo Jisshiken):

- This is a powerful, property-like right registered in the Patent Register (Patent Act, Article 77).

- It grants the licensee the exclusive right to work the patented invention within the scope defined by the license agreement (territory, time, field of use).

- Crucially, even the patentee is excluded from working the invention within the scope of the sen'yo jisshiken.

- Because it's a registered exclusive right, the licensee can directly sue third-party infringers for damages and injunctions.

- Requires registration at the Japan Patent Office (JPO) to take effect (Patent Act, Article 98). Its creation, transfer, modification, extinguishment, or restrictions on disposition must be registered.

- Ordinary/Non-Exclusive License (通常実施権, Tsūjō Jisshiken):

- This is a contractual right, not a registered property right in the same way as a sen'yo jisshiken (Patent Act, Article 78).

- It grants the licensee permission to work the patented invention within the scope agreed upon.

- It is non-exclusive by default, meaning the patentee can grant similar licenses to others and can continue working the invention themselves, unless contractually restricted.

- Registration at the JPO is generally not required for the license to be effective between the licensor and licensee. However, registration can provide certain protections against subsequent acquirers of the patent right or holders of a later-registered sen'yo jisshiken (Patent Act, Article 99). In practice, registration of tsūjō jisshiken is less common than for sen'yo jisshiken.

- Tsūjō jisshiken holders generally cannot directly sue infringers based on their license right alone; enforcement typically relies on the patentee.

- Exclusive Ordinary License (独占的通常実施権, Dokusenteki Tsūjō Jisshiken):

- This is a common hybrid arrangement in practice, though not explicitly defined as a separate category in the Patent Act like sen'yo jisshiken.

- It combines a tsūjō jisshiken (the right to work the patent) with a contractual obligation from the licensor not to grant licenses to any third parties within the specified scope (and sometimes, an obligation for the licensor themselves not to work the patent within that scope – a "sole" license).

- The licensee's right to work the patent stems from the tsūjō jisshiken, while the exclusivity stems from the contract.

- If the licensor breaches the exclusivity promise (e.g., licenses a third party), the licensee's recourse is typically for breach of contract against the licensor, not a direct patent infringement claim against the third party based solely on the license.

- Non-Assertion Agreements: Similar to US practice, parties may agree contractually that one party will not assert its patent rights against the other's activities. While functionally similar to a license (preventing an infringement suit), it doesn't formally grant a tsūjō jisshiken under the Patent Act, which could have implications regarding rights against third parties or transferability. Clarity in drafting is essential if a specific legal form (license vs. non-assertion) is intended.

Key Clauses & Negotiation Points for US Licensors/Licensees

Drafting a robust patent license agreement requires careful attention to detail. From a US perspective, here are key areas to consider when dealing with Japanese patents and partners:

- Grant Clause (Scope of License): Precision is paramount.

- Licensed Patent(s): Clearly identify by patent number(s). For pending applications, use the application number. Specify whether future patents (continuations, divisionals, patents on improvements) are included.

- Licensed Product/Field: Define the specific products, services, or fields of use covered by the license. Is it for all possible applications or restricted to certain areas?

- Licensed Activities: Specify which acts of "working" (jisshi) are permitted (e.g., make, use, sell, offer for sale, import). Granting rights for all acts is common but can be restricted.

- Territory: Define the geographical scope (e.g., Japan only, specific regions, worldwide).

- Duration: Specify the term. Is it for the life of the patent? A fixed number of years? Does it terminate upon patent expiry or invalidation? (See Royalty discussion below).

- Exclusivity: Clearly state whether the license is exclusive (dokusenteki tsūjō jisshiken or sen'yo jisshiken), sole (exclusive except for the licensor), or non-exclusive (tsūjō jisshiken).

- Sublicensing: Does the licensee have the right to grant sublicenses? If so, under what conditions (e.g., licensor approval, royalty sharing, scope limitations)? Under the Patent Act, tsūjō jisshiken generally cannot be sublicensed without the licensor's consent (Article 77(4) regarding sen'yo jisshiken implies this, and Article 78 is silent, leading to the interpretation requiring consent).

- Royalties & Payment:

- Types: Lump sum, running royalties (based on sales, units, etc.), minimum royalties, milestone payments, or combinations.

- Calculation: Define the royalty base (e.g., net sales price – clearly defining deductions), royalty rate, and calculation methodology.

- Payment Terms: Frequency, currency (JPY or USD?), payment method, reporting requirements (licensee reports sales), audit rights for the licensor.

- Withholding Tax: Royalties paid from Japan to a US entity are subject to Japanese withholding tax. The Japan-US tax treaty generally reduces this rate (currently often 0% for patent royalties if treaty procedures are followed, but verification is essential). The agreement should specify who bears the burden of withholding tax or if payments are "grossed up."

- Post-Termination/Expiry Royalties: This is a complex area, especially for hybrid patent/know-how licenses. As illustrated by a case similar to the one discussed in the Jurist source (related to Osaka High Court, May 13, 2022, though specific citations are omitted here per user request), Japanese courts may find that running royalty obligations tied primarily to a patent right cease when the patent right expires or is invalidated, even if the agreement also includes know-how transfer. If royalties are intended to continue for know-how after patent expiry, the agreement must clearly allocate a distinct portion of the royalty to the know-how and demonstrate the know-how's ongoing value and confidentiality. Simply stating the royalty covers both may not suffice if the patent was the core element. Conversely, if a licensee anticipates challenging validity or facing expiry, ensuring royalties are explicitly tied to the valid and subsisting patent term is advantageous. Agreements might also explicitly state whether royalties are refundable (or not) upon invalidation – a non-refundable clause is common practice.

- Improvements & Grant-Backs: How are improvements to the licensed technology handled? Are there obligations for the licensee to grant back rights to their own improvements to the licensor? Grant-back clauses requiring assignment or exclusive licenses, especially without fair compensation, can raise antitrust concerns under the JFTC's IP Guidelines (chizai gaidorain). Non-exclusive grant-backs are generally considered less problematic.

- Patent Marking: Is the licensee required to mark licensed products with the Japanese patent number? While not mandatory for recovering damages in Japan (unlike the US), it can serve as notice.

- Representations and Warranties:

- Validity/Enforceability: Japanese licensors are often reluctant to provide strong warranties regarding patent validity or enforceability, viewing patents as rights granted after examination but still potentially subject to challenge. Expect negotiation on this point.

- Non-infringement: Warranties that the licensed technology does not infringe third-party rights are also often heavily negotiated or limited in scope.

- Right to Grant: A warranty that the licensor has the right to grant the license is more standard.

- Confidentiality: Crucial if trade secrets or know-how are shared. Define the scope of confidential information, the duration of the obligation (which may need to survive contract termination, especially for know-how), and permitted uses/disclosures.

- Patent Prosecution and Maintenance: Who is responsible for prosecuting pending applications included in the license and for paying maintenance fees (annuities) for granted patents? Typically the licensor retains control, but the licensee may seek step-in rights if the licensor fails to maintain the patent.

- Infringement:

- Third-Party Infringement: Define responsibilities for monitoring and enforcing the patent against infringers. Who has the primary right to sue? Who controls the litigation? How are costs and recovered damages shared? A tsūjō jisshiken holder cannot sue directly, so cooperation clauses requiring the licensor (patentee) to take action are important.

- Third-Party Claims: How are claims that the licensed activities infringe a third party's patent handled? Indemnification clauses are often heavily negotiated.

- Term and Termination:

- Term: As discussed under Grant Clause/Royalties.

- Termination Triggers: Grounds for termination (e.g., material breach after a cure period, bankruptcy/insolvency, patent invalidation, licensee challenge to validity).

- Consequences: What happens upon termination? Cessation of licensed activities, return of confidential information, final royalty payments, survival of certain clauses (confidentiality, liability limitations).

- Governing Law and Dispute Resolution:

- Governing Law: Often Japanese law, especially if the licensor is Japanese and the patent is Japanese.

- Dispute Resolution: Litigation in Japanese courts (Tokyo or Osaka District Courts have IP specialization) or arbitration are common choices. The Japan Commercial Arbitration Association (JCAA) is a frequently chosen arbitral institution, though others like the ICC are also used. Arbitration offers neutrality, confidentiality, and potentially easier enforcement internationally (via the New York Convention) compared to court judgments.

Interaction with Know-How and Technical Assistance

Many patent licenses, particularly in complex technology fields, involve the transfer of related know-how, trade secrets, or technical assistance.

- Hybrid Licenses: When an agreement covers both patent rights and know-how, it's crucial to distinguish the two legally and commercially. The patent license grants a right under a statutory monopoly, while the know-how component primarily involves the contractual disclosure of valuable, non-public information and permission to use it, usually coupled with confidentiality obligations.

- Defining Know-How: Clearly define the scope of the know-how being transferred. Is it existing information only, or does it include future updates? How is it documented and delivered?

- Payment Allocation: As noted earlier, if payment (especially running royalties) is intended for the know-how component independently of the patent, the agreement should clearly allocate specific value/payment streams to it. This is vital if payments are expected to continue after patent expiry or invalidation. Demonstrating the distinct value and continued confidentiality/use of the know-how will be key.

- Confidentiality Duration: Know-how protection relies on secrecy. Confidentiality obligations should extend for a commercially reasonable period, potentially long after the agreement (and any related patents) expire, as long as the information retains its secret status and value.

- Technical Assistance: If the licensor provides training or technical support, the scope, duration, and cost (if any) should be clearly specified.

Antitrust Considerations: The Antimonopoly Act (Dokkinho)

Patent licensing agreements in Japan are subject to the Antimonopoly Act (Dokkinho). While the exercise of rights under the Patent Act itself is generally exempt (Article 21), licensing practices can fall foul of prohibitions against unreasonable restraint of trade (cartels) or unfair trade practices (abuse of superior bargaining position, etc.). The Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) provides guidance through its "Guidelines Concerning the Use of Intellectual Property under the Antimonopoly Act" (chizai gaidorain). Key areas of potential concern include:

- Tying Arrangements: Requiring the licensee to purchase non-patented goods or raw materials from the licensor or a designated source can be problematic unless necessary for ensuring the effectiveness of the licensed patent (e.g., quality control).

- Resale Price Maintenance: Restricting the licensee's selling price for licensed products is generally prohibited.

- Restrictions on R&D: Unreasonably restricting the licensee's own research and development activities, especially in fields outside the scope of the licensed patent, can be viewed as anti-competitive.

- Territorial, Customer, or Field of Use Restrictions: While generally permissible within the scope of the licensed patent, restrictions extending beyond the patent's scope or imposed after the patent expires can raise issues.

- No-Challenge Clauses: Clauses prohibiting the licensee from challenging the validity of the licensed patent are generally considered problematic as they can maintain potentially invalid monopolies. However, clauses allowing the licensor to terminate the agreement if the licensee challenges validity are typically permissible.

- Grant-Backs: As mentioned, requiring assignment or exclusive licenses back on licensee improvements can be problematic, especially if non-reciprocal or without fair compensation. Non-exclusive grant-backs are usually acceptable.

- Royalty Issues: Charging royalties on products not using the licensed patent, or continuing to charge patent-based royalties after the patent has expired or been invalidated (unless clearly attributable to separate know-how), can be considered an unfair trade practice.

Parties should review proposed license terms against the JFTC's IP Guidelines to mitigate antitrust risks.

Conclusion: Charting a Course for Successful Licensing

Successfully negotiating and managing patent license agreements in Japan requires more than just translating a US template. It demands an understanding of the nuances of Japanese patent law (including tsūjō and sen'yo jisshiken), careful attention to contractual drafting to clearly define scope and obligations, awareness of post-grant patent vulnerabilities (invalidation/correction), strategic consideration of royalty structures (especially in hybrid deals), and robust compliance with Japanese antitrust law under the Dokkinho and JFTC guidelines.

While the Japanese legal framework provides established mechanisms for licensing, cultural factors in negotiation and relationship management also play a role. By approaching Japanese patent licensing with thorough preparation, clear drafting informed by local legal principles, and sensitivity to potential regulatory pitfalls like antitrust rules, US companies can effectively leverage licensing to achieve their strategic objectives in the vital Japanese market.

- Protecting Innovation: Patent Enforcement and Management Strategies in Japan

- Standard Essential Patents in Japan: Navigating a Globalized Licensing and Dispute Landscape

- Balancing IP Rights and Antitrust: Patent Enforcement Against Recycled Goods in Japan

- Japan Patent Office – Examination Guidelines for Patent and Utility Model