Equality in Nationality: Japanese Supreme Court Strikes Down Discriminatory Clause for Children of Unmarried Parents

Date of Judgment: June 4, 2008

Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

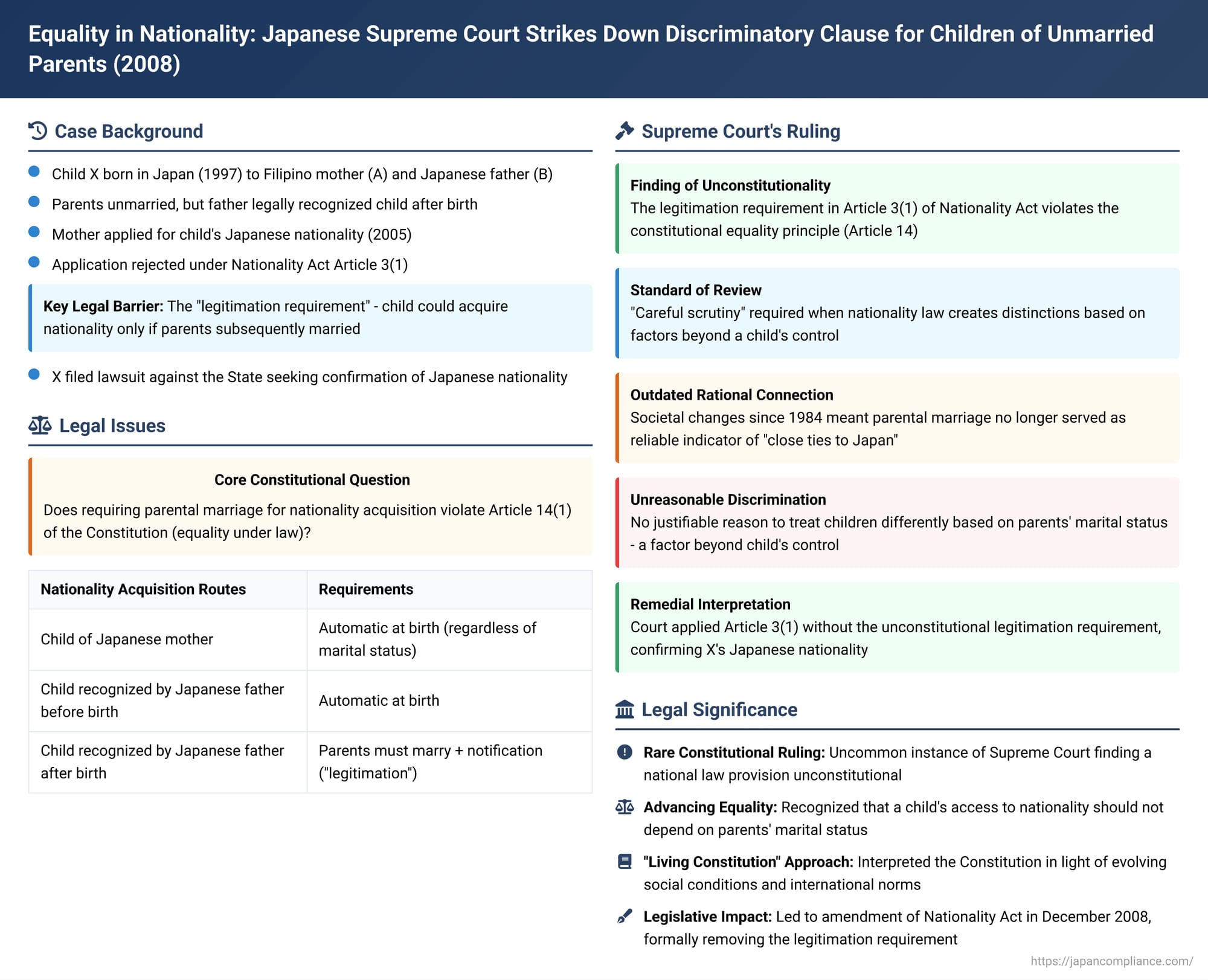

The conditions under which a person acquires nationality are fundamental to their legal status and rights within a state. While legislatures are generally granted broad discretion in setting these conditions, such laws can face constitutional challenges if they create distinctions that are deemed unreasonably discriminatory. A landmark Grand Bench decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on June 4, 2008, addressed such a challenge, finding a key provision of Japan's Nationality Act unconstitutional for discriminating against children born out of wedlock to Japanese fathers and non-Japanese mothers based on the marital status of their parents.

The Factual Background: A Child Denied Nationality Due to Parents' Marital Status

The case was brought by X, a child born in Japan in 1997.

- X's mother, A, was a Filipino national residing in Japan.

- X's father, B, was a Japanese national.

- X was born out of wedlock but was legally recognized by B (the Japanese father) after birth. The parents, A and B, did not subsequently marry.

- In 2005, A, acting on X's behalf, submitted a notification to Japan's Minister of Justice for X to acquire Japanese nationality. This was based on X having been recognized by a Japanese father.

- However, this notification was rejected. The reason was that X did not meet all the conditions stipulated in Article 3, paragraph 1 of Japan's Nationality Act as it then stood.

At the time of X's application, Article 3(1) of the Nationality Act allowed a child under the age of 20 (who was not already Japanese) to acquire Japanese nationality by notification if, among other requirements, the child had been recognized by a father or mother who was a Japanese national at the time of the child's birth, and that parent was currently (or at death) a Japanese national. Critically, the provision also mandated that the child must have "acquired the status of a legitimate child through the marriage of his/her parents and his/her recognition by them." This meant that for a child like X, born out of wedlock to a Japanese father and a non-Japanese mother and recognized post-natally by the father, acquiring Japanese nationality by notification under this article was only possible if the parents subsequently married, thereby legitimating the child. Since X's parents had not married, X was denied nationality under this provision.

X filed a lawsuit against Y (the State of Japan), seeking confirmation of Japanese nationality and arguing that this "legitimation requirement" (i.e., the requirement of parental marriage) in Article 3(1) of the Nationality Act violated Article 14, paragraph 1 of the Constitution of Japan, which guarantees equality under the law and prohibits discrimination.

The Tokyo District Court found the legitimation requirement unconstitutional and confirmed X's Japanese nationality (employing a re-interpretive approach to the statute). The Tokyo High Court, however, while acknowledging potential unconstitutionality, reasoned that even if the provision were void, it would not automatically create a new pathway for X to acquire nationality, and thus dismissed X's claim. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Challenge: Discrimination Under the Constitution's Equality Clause

The core issue before the Supreme Court was whether the Nationality Act's requirement for parental marriage as a condition for a post-natally recognized child of a Japanese father and non-Japanese mother to acquire Japanese nationality by notification constituted unreasonable discrimination contrary to Article 14(1) of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Finding the Distinction Unconstitutional

The Supreme Court, in a significant Grand Bench ruling, reversed the High Court's decision and ultimately upheld the first instance's conclusion that X had acquired Japanese nationality, though it provided its own distinct reasoning for the remedy.

1. Scrutiny of Nationality Laws under the Constitution:

The Court acknowledged that Article 10 of the Constitution entrusts the legislature with broad discretion in determining the requirements for Japanese nationality, considering various national factors. However, it firmly stated that if distinctions created by nationality laws lead to unreasonable discrimination, they can violate the equality principle of Article 14(1).

The Court emphasized that Japanese nationality is a crucial legal status for enjoying fundamental human rights and public benefits in Japan. Furthermore, whether a child is legitimated through their parents' marriage is a matter entirely beyond the child's own will or effort. Therefore, the Court declared that distinctions based on such a factor for acquiring Japanese nationality necessitate "careful scrutiny" (慎重に検討 - shinchō ni kentō) regarding their reasonableness. This signaled a potentially heightened standard of review.

2. Loss of Rational Connection between Legislative Purpose and Means:

The legislative purpose behind Article 3(1) of the Nationality Act was to supplement the primary principle of jus sanguinis (nationality by descent) by allowing post-birth acquisition of nationality for children with a Japanese parent, provided they had a close tie with Japan. The legitimation requirement was initially seen as an indicator of such ties, often implying integration into a Japanese father's family life.

However, the Supreme Court found that due to significant societal changes since the provision's enactment in 1984—including an increase in out-of-wedlock births, diverse family structures, growing international exchange leading to more children of mixed-nationality parentage, and evolving international norms against discrimination based on birth—the requirement of parental marriage had lost its rational connection to the legislative purpose of ensuring a child's meaningful link to Japan. The mere fact of parental marriage (or lack thereof) was no longer a reliable measure of a child's connection to Japan.

3. Unreasonable Discrimination:

The Court identified several ways in which the legitimation requirement created unreasonable discrimination:

- It treated children recognized post-natally by their Japanese fathers differently based solely on whether their parents married, a factor outside the children's control.

- This contrasted sharply with:

- Children born to Japanese mothers, who acquire Japanese nationality at birth regardless of their parents' marital status.

- Children recognized by their Japanese fathers before birth (胎児認知 - taiji ninchi), who also acquire Japanese nationality at birth.

The Supreme Court found no justifiable reason, based on the degree of connection to Japan, for this significantly disadvantageous treatment of post-natally recognized children whose parents did not marry. Arguments about preventing "sham recognitions" solely for nationality purposes were deemed insufficient to justify such broad discrimination.

The Court concluded that the distinction created by the legitimation requirement in Article 3(1) had, by the time X applied for nationality, become an unreasonable discrimination lacking a rational basis, thereby violating Article 14, paragraph 1 of the Constitution.

4. The Remedy: Constitutional Re-interpretation of Article 3(1):

Having found the legitimation requirement unconstitutional, the Supreme Court addressed the remedy.

- It rejected the idea of declaring Article 3(1) entirely void, as this would also prevent legitimated children from acquiring nationality by notification, which would contradict the legislature's clear intent to provide a path for post-birth nationality acquisition.

- Instead, the Court adopted a remedial interpretation of the statute. It held that, to bring the law into conformity with the Constitution's equality principle and the Nationality Act's overarching principle of bilateral jus sanguinis, Article 3(1) should be applied by excluding the unconstitutional legitimation requirement.

- The New Interpretation: A child born out of wedlock to a Japanese father and a non-Japanese mother, who is recognized by the father after birth, can acquire Japanese nationality by notification if they meet all the other conditions stipulated in Article 3(1) (e.g., being under 20 years of age, the recognizing father being a Japanese national at the time of the child's birth and currently (or at death) being a Japanese national). The marriage of the parents is no longer a prerequisite for this route of nationality acquisition.

- The Court reasoned that this approach was not judicial legislation but rather a constitutional interpretation of the existing statute to rectify the identified unconstitutionality and provide direct relief to those affected by the discrimination.

- Application to X: Since X met all the other requirements of Article 3(1) apart from the now-excised legitimation requirement, the Supreme Court concluded that X had lawfully acquired Japanese nationality upon the filing of the notification.

Significance and Impact

This 2008 Grand Bench decision was a momentous one in Japanese constitutional and nationality law:

- Rare Finding of Unconstitutionality: It is relatively uncommon for the Japanese Supreme Court to find a provision of a national law unconstitutional. This ruling, particularly in the sensitive area of nationality, underscored the Court's role as a guardian of constitutional rights.

- Advancement of Equality: The decision significantly advanced the principle of equality for children born out of wedlock, recognizing that their access to nationality should not depend on the marital status of their parents—a factor entirely beyond their control.

- "Living Constitution" Approach: The judgment demonstrated the Supreme Court's willingness to interpret the Constitution and statutes in light of evolving social conditions, international human rights norms, and changing global legal standards.

- Direct Impact and Legislative Response: The ruling had an immediate and direct impact, providing a pathway to Japanese nationality for many children who were similarly situated to X. In response to this landmark decision, the Japanese Diet amended the Nationality Act in December 2008. The revised Article 3(1) formally removed the legitimation requirement for children recognized by their Japanese fathers, aligning the statute with the Supreme Court's constitutional interpretation.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2008 decision in the Nationality Act case represents a significant victory for the principle of equality under the law in Japan. By finding the legitimation requirement in Article 3(1) of the Nationality Act unconstitutional and re-interpreting the provision to allow for nationality acquisition by recognized children regardless of their parents' marital status, the Court not only provided relief to the plaintiff but also prompted important legislative reform. This case stands as a powerful example of the judiciary's role in ensuring that national laws conform to fundamental constitutional values and adapt to the evolving realities of society and international human rights standards.