Enterprise Loss Due to Harm to Key Person: A 1968 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on "Indirect Damage"

Date of Judgment: November 15, 1968

Case Name: Claim for Solatium and Damages

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

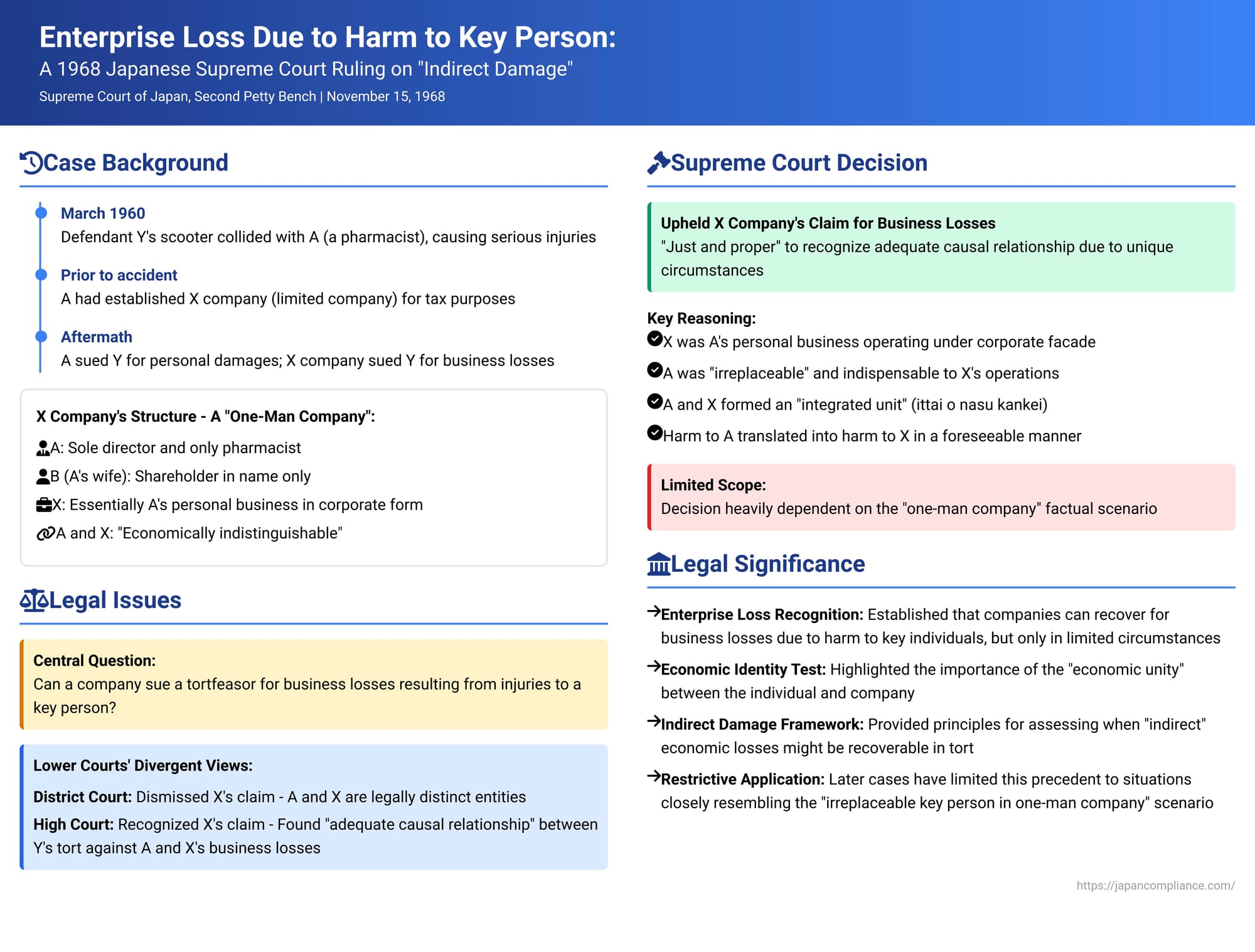

When an individual is injured due to a wrongful act (a tort), they are generally entitled to compensation for their personal losses, such as medical expenses and lost income. But what happens if that injured individual is a key person in a business, and their injury causes the business itself to suffer financial losses? Can the business, as a separate legal entity, directly sue the tortfeasor for these "enterprise losses"? This complex issue of "indirect damage" was addressed by the Japanese Supreme Court in a notable decision on November 15, 1968, concerning a so-called "one-man company."

A Pharmacist Injured, A Company's Loss: The Factual Background

The case involved a traffic accident with repercussions for a closely-held company:

- The Accident and the Injured Party: In March 1960, Y, while negligently driving a scooter without a license (the scooter was owned by C), collided with A, causing A facial fractures, a decline in vision, and other injuries. A was a pharmacist and the sole director of a limited company, X.

- The Company's Structure: X company was, for all practical purposes, the personal business of A. The judgment detailed A's business history: he initially ran a pharmacy as a sole proprietorship, then briefly converted it to a limited partnership which was subsequently dissolved, and then continued again as a sole proprietorship. Finally, for tax reasons, A established X as a limited company (Yūgen Kaisha) in October 1958. The shareholders of X were A and his wife, B. A was the sole director and legally represented the company. B was a shareholder in name only and not a director. X company employed no other pharmacists besides A. The Court found that X was essentially A's personal business merely operating under a corporate form, that A was indispensable to X's existence, and that A and X were economically indistinguishable.

- The Lawsuits:

- A (the injured pharmacist) sued Y (the scooter driver) and C (the scooter owner) for his personal damages, including medical expenses and solatium (compensation for pain and suffering). (A did not claim lost personal income, presumably because X company continued to pay his salary [cite: 1]).

- X company also sued Y and C, claiming that due to A's injuries and reduced work capacity, X company had suffered business losses (e.g., lost profits) and demanded compensation for these.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The first instance court upheld A's personal claim against Y but dismissed X company's claim against Y. It reasoned that A and X company were legally distinct entities. Claims by X and A against C were also dismissed.

- The High Court (second instance) took a different view regarding X company's claim. It stated that for a tortfeasor to be liable for negligence, it is sufficient that they foresaw or should have foreseen that their act would cause some damage to someone; it is not necessary that they foresaw damage to a specific person. It then held that even if harm is indirectly caused to a third party (like X company) as a result of a direct tort against another person (A), the tortfeasor is liable for the third party's damages as long as there is an "adequate causal relationship" (相当因果関係 - sōtō inga kankei) between the tortious act and the third party's damage. The High Court found such an adequate causal relationship between A's injuries and X company's business losses and thus partially upheld X company's claim against Y.

Y (the scooter driver) appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that even if A's work efficiency decreased due to his injuries, this was a matter for X company to address internally, and there was no adequate causal relationship between Y's act of injuring A and X company's subsequent business losses.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Affirming Company's Claim in Special Circumstances

The Supreme Court, on November 15, 1968, dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision to allow X company's claim for business losses.

The Court's reasoning focused heavily on the specific nature of X company:

- It reiterated the High Court's findings regarding the structure of X company: it was effectively A's personal business operating under a corporate facade. A was the sole director, the company had no other pharmacists, and the other shareholder (A's wife) was nominal. The company's existence was inseparable from A, who was indispensable to its operations. Economically, A and X company were "a single entity."

- Conclusion on Causation: Given these specific factual circumstances, the Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment – which recognized an adequate causal relationship between Y's wrongful act injuring A and the subsequent loss of profits suffered by X company – to be "just and proper."

- The Court acknowledged that X company was, formally, an "indirect victim." However, due to the complete economic identity between A and X company, and A's irreplaceable role, the harm to A directly translated into harm to X company's business operations in a foreseeable manner.

Unpacking "Enterprise Loss" and Indirect Damage

This 1968 Supreme Court decision is a key case in the Japanese legal discourse on "enterprise loss" (企業損害 - kigyō songai) – damages suffered by a business entity as a result of a tort committed against one of its key individuals.

- The Problem of "Indirect Damage": When a person is injured, the most direct losses are to that individual (medical bills, lost wages, pain and suffering). If that individual is an employee or owner of a business, their injury might also cause consequential losses to the business (e.g., lost sales, disruption of projects, costs of hiring a temporary replacement). Traditionally, tort law is often hesitant to award damages for such "indirect" or "relational" economic losses suffered by third parties, due to concerns about foreseeability and the potential for an unmanageable scope of liability (the "floodgates" argument).

- The Supreme Court's Approach – Focusing on "Economic Identity":

- The Supreme Court in this case did not lay down a broad rule allowing all businesses to claim for losses resulting from injuries to their employees or key persons.

- Instead, its decision was heavily grounded in the specific factual finding that X company was a "one-man company" (個人会社 - kojin gaisha, a colloquial term) that was, in substance, indistinguishable from A, its sole director and pharmacist.

- The factors emphasized were:

- X was a company "in name only."

- Real control was concentrated in A.

- A was "irreplaceable" as an organ of the company.

- Economically, A and X company formed an "integrated unit" (一体をなす関係 - ittai o nasu kankei).

- Because of this tight integration, the harm to A was, in effect, a direct harm to the economic unit that X company represented. The Court viewed the "corporate veil" as being very thin in this instance, allowing it to see the loss to A as almost synonymous with a loss to X.

- "Adequate Causation" and Foreseeability:

- The High Court had framed its decision in terms of "adequate causation," stating that a tortfeasor doesn't need to foresee harm to a specific person, only that some harm to someone is foreseeable. The Supreme Court, in affirming the High Court's conclusion, implicitly accepted that in the unique circumstances of a one-man company like X, the business losses were an adequately foreseeable consequence of severely injuring A.

- The commentary notes that the Supreme Court's decision does not explicitly engage with the traditional "Article 416 analogy" (applying contract damage scope rules to torts), but rather seems to lean on the specific facts establishing an economic identity, which then supports the finding of adequate causation for X company's losses.

- Limited Scope of the Ruling:

- Due to its strong reliance on the "one-man company" facts, the direct precedential value of this case for larger, more complex corporations where key personnel are generally replaceable (even if with difficulty or cost) is limited.

- Subsequent Supreme Court cases have been more restrictive in allowing claims for enterprise losses when the injured party was merely an employee, even a key one, in a larger organization. For example, a later Supreme Court case (1979) denied a claim for lost profits by a company whose employee was injured, finding the causal link too remote.

- Lower courts have generally followed this restrictive trend, typically only allowing enterprise loss claims when the facts very closely mirror the "economic identity" and "irreplaceability" scenario of the 1968 Osaka Alkali-related case (though the defendant in this case was not Osaka Alkali, the judgment text refers to the plaintiff as X and the initial individual victim as A; the commentary clarifies the underlying business was a pharmacy run by A, then incorporated as X).

- Theoretical Approaches to Enterprise Loss:

Legal scholars in Japan have debated various theoretical approaches to enterprise loss claims:- Independent Tort Against the Company: One view is that injuring a key person can, in some circumstances, constitute a direct (though perhaps indirect in mechanism) tort against the company itself, if the company's interests were foreseeably and directly impacted. This requires a separate assessment of duty, breach, causation, and damage for the company.

- Scope of Damages from the Tort Against the Individual: Another view treats the company's loss as part of the scope of damages flowing from the original tort committed against the individual key person. The question then becomes one of "adequate causation" or whether the company's loss falls within the range of harms for which the tortfeasor should be liable. The 1968 Supreme Court judgment appears to lean towards this latter approach, finding the company's loss to be within the scope of adequately caused damages due to the special "one-man company" circumstances.

Conclusion

The 1968 Supreme Court decision in this "enterprise loss" case established that a company can, under specific and limited circumstances, recover damages for business losses resulting from a tortious injury to its key individual. The critical factor in this ruling was the Court's finding that the company was, in essence, the alter ego of the injured individual – a "one-man company" where the individual was irreplaceable and their personal economic fate was inextricably intertwined with that of the company. In such cases, the injury to the individual is deemed to have a sufficiently direct and foreseeable causal link to the company's operational losses. However, the ruling did not open the floodgates for general claims of enterprise loss. For larger or less personally integrated businesses, proving that losses due to injury to an employee or director are a sufficiently direct and foreseeable consequence of a tort against that individual remains a significant legal challenge in Japan. The case underscores the importance of the specific factual matrix, particularly the degree of identity between the injured individual and the enterprise, in determining the recoverability of such indirect economic losses.