Enforcing U.S. Judgments in Japan: Supreme Court on Jurisdiction in Trade Secret Case

Date of Judgment: April 24, 2014

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

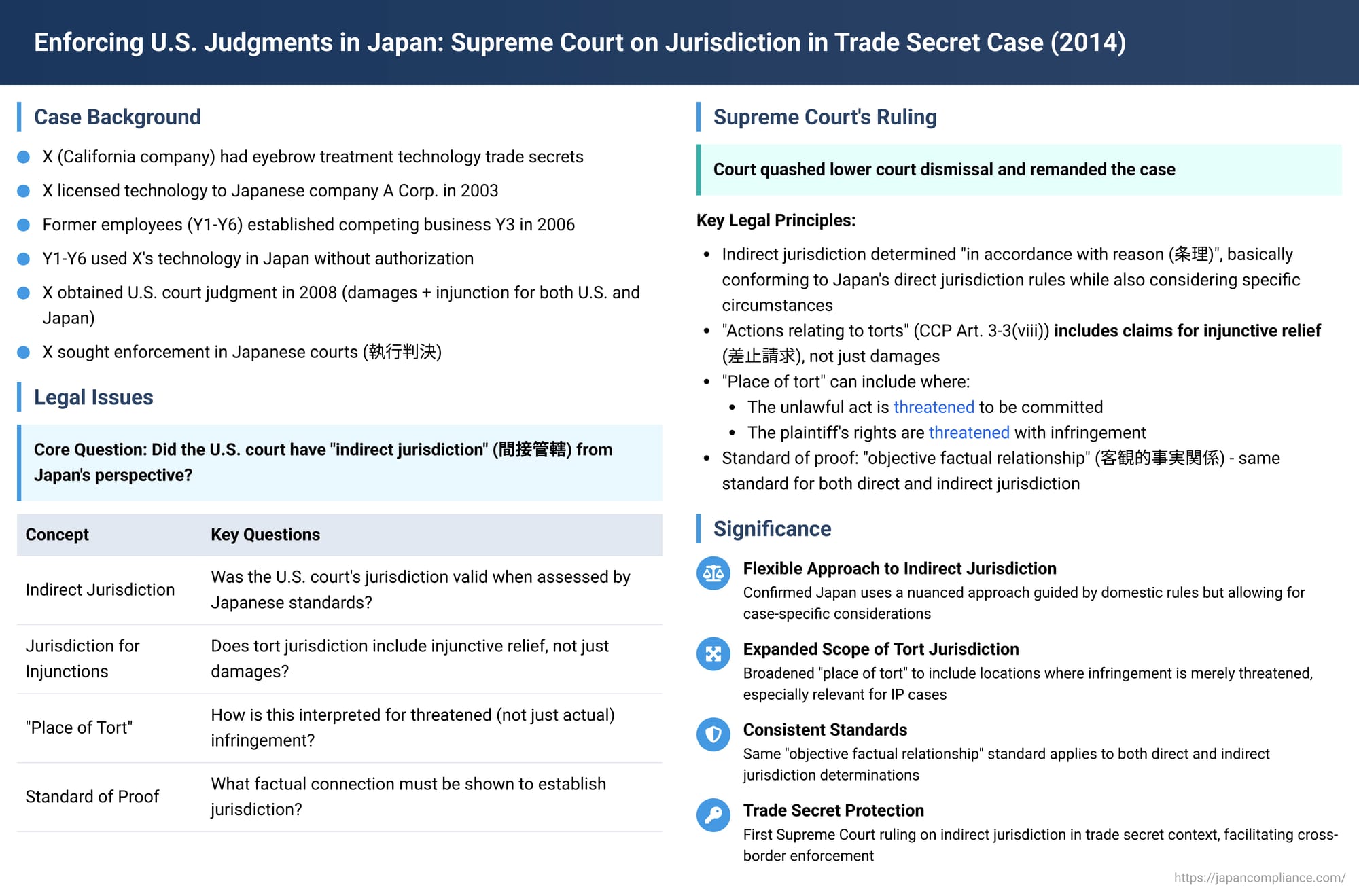

When a company obtains a favorable judgment in a foreign court, seeking to enforce that judgment in Japan involves navigating Japan's rules on the recognition and enforcement of foreign judicial decisions. A critical hurdle is establishing that the foreign court had "indirect jurisdiction" (間接管轄 - kansetsu kankatsu)—meaning, jurisdiction from the perspective of Japanese law. A Supreme Court decision on April 24, 2014, provided significant clarification on these standards, particularly in a case involving the enforcement of a U.S. judgment for trade secret misappropriation that included both monetary damages and injunctive relief extending to conduct in Japan and the U.S.

The Factual Background: Trade Secret Misappropriation and a U.S. Judgment

The dispute centered on eyebrow treatment technology:

- X (Plaintiff): A California-based corporation holding proprietary technology and information related to eyebrow treatment services ("the Technology"), which it considered a trade secret.

- A Corp.: A Japanese corporation to whom X granted an exclusive license in December 2003 to use the Technology in Japan.

- Y1 and Y2 (Defendants): Former employees of A Corp. As part of the licensing agreement, X disclosed the Technology to Y1 and Y2 in April 2004 at X's facility in California. A Corp. subsequently launched eyebrow treatment salons in Japan.

- Y3 (Defendant Company): In February 2006, Y1 and Y2 established Y3, a new Japanese corporation. They resigned from A Corp. around the same time. Y3 then opened its own eyebrow treatment salons in Japan and also conducted classes teaching related techniques, with Y1 and Y2 using the Technology as directors of Y3.

- Y4, Y5, and Y6 (Defendants): Also former employees of A Corp., they resigned by late 2006 and were subsequently employed by Y3, where they also used the Technology in Japan.

- The U.S. Lawsuit and Judgment: In May 2007, X sued Y1-Y6 and Y3 (collectively "Y et al.") in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California. X alleged unlawful disclosure and use of its Technology (trade secrets under California law) and sought damages and an injunction. In October 2008, the U.S. court issued a judgment in favor of X ("U.S. Judgment"). This judgment ordered Y et al. to pay damages and, importantly, enjoined them from unlawfully disclosing or using the Technology both in Japan and in the United States.

- Enforcement Action in Japan: X then sought an enforcement judgment (執行判決 - shikkō hanketsu) in Japanese courts to enforce parts of the U.S. Judgment against Y et al. in Japan. This included a portion of the compensatory damages (excluding any punitive damages component) and the injunctive relief.

The Japanese lower courts (both first instance and High Court) dismissed X's request for an enforcement judgment. They primarily found that X had not sufficiently proven the "objective factual relationship" required to establish that the U.S. court had indirect jurisdiction based on the place of tort (i.e., a sufficient connection to California from the perspective of Japanese jurisdictional rules). X appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Question: Did the U.S. Court Have Jurisdiction from Japan's Perspective (Indirect Jurisdiction)?

For a foreign judgment to be recognized and enforced in Japan, one of the key requirements under Article 118(i) of Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) is that the foreign court must have had jurisdiction over the case, as assessed by Japanese standards (this is "indirect jurisdiction" or "recognition jurisdiction" - 承認管轄, shōnin kankatsu). The central issue was whether the U.S. court met this jurisdictional threshold.

The Supreme Court's Key Rulings on Indirect Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's dismissal and remanded the case for further proceedings, providing important clarifications on how indirect jurisdiction is determined:

1. General Standard for Determining Indirect Jurisdiction:

The Court reaffirmed its established approach (from a 1998 precedent): The existence of indirect jurisdiction for a foreign judgment in non-personal status matters should be determined "in accordance with reason (jōri), from the perspective of whether it is appropriate for Japan to recognize the foreign court's judgment, by basically conforming to Japan's Code of Civil Procedure provisions on international adjudicatory jurisdiction, while also considering the specific circumstances of each individual case."

This means that while Japan's own rules for direct international jurisdiction (CCP Articles 3-2 to 3-12) are the primary reference, the determination of indirect jurisdiction is not necessarily a strict "mirror image" of these rules but allows for flexibility based on the principles of fairness and the appropriateness of recognition in the specific context.

2. Tort Jurisdiction (CCP Art. 3-3(viii)) Includes Claims for Injunctive Relief:

The Supreme Court clarified that the term "actions relating to torts" in CCP Article 3-3(viii) (which grants Japanese courts direct jurisdiction if "the place where the tort was committed" is in Japan) is not confined to claims for monetary damages for past wrongs. It also encompasses actions for injunctive relief (差止請求 - sashitome seikyū) brought by a party whose rights or legally protected interests have been infringed or are under threat of infringement by an unlawful act.

3. "Place of Tort" for Threatened Infringement (Relevant to Injunctions):

For claims seeking injunctive relief, especially where the infringement is only threatened, the Court expanded the interpretation of "the place where the tort was committed." It held that this phrase can include:

- The place where the unlawful act is threatened to be committed, or

- The place where the plaintiff's rights or legally protected interests are threatened with infringement.

4. Standard of Proof for Jurisdictional Facts in Indirect Jurisdiction Cases:

The Court addressed what must be proven to satisfy the jurisdictional test:

- "Objective Factual Relationship": Referencing its 2001 "Ultraman" case (see case 79 in this series), the Court reiterated that for direct tort jurisdiction in Japan, the plaintiff generally needs to prove an "objective factual relationship" (客観的事実関係 - kyakkanteki jijitsu kankei). This means showing either that the defendant's act in Japan caused harm to the plaintiff, or that the defendant's act (wherever committed) caused harm to the plaintiff in Japan.

- Same Standard for Indirect Jurisdiction: The Court stated that since the determination of indirect jurisdiction should "basically conform" to Japan's direct jurisdiction rules, the standard and nature of what needs to be proven should not be different.

- Application to Injunctive Relief for Threatened Harm: In the context of an injunctive claim (where actual damage is not a prerequisite, as a mere threat can suffice), to establish that "the place where the tort was committed" was within the foreign judgment country (for indirect jurisdiction purposes), it is sufficient for the plaintiff to prove an objective factual relationship demonstrating that:

- The defendant threatened to commit an act infringing the plaintiff's rights/interests within that foreign judgment country, OR

- The plaintiff's rights/interests were threatened with infringement within that foreign judgment country.

This proof is sufficient even if no actual infringing act by the defendant had yet occurred in the judgment country, and even if no actual infringement of the plaintiff's rights had yet materialized there.

Application to the Trade Secret Case and Remand

The Supreme Court found that the lower courts had erred in their approach:

- The U.S. Judgment included an injunction against Y et al.'s unlawful acts not only in Japan but also within the U.S. (California law, the basis of the judgment, allows injunctions for actual or threatened trade secret misappropriation).

- The lower courts had focused on whether X had proven damage occurring in the U.S., which is more pertinent to a damages claim.

- The Supreme Court clarified that for the injunctive part of the U.S. Judgment to be recognized (based on the U.S. court having indirect jurisdiction from Japan's viewpoint), the correct inquiry for the Japanese court was whether there was sufficient proof of an objective factual relationship indicating a threat of Y et al. infringing X's trade secret rights within the U.S. (California).

- Since the lower courts had not adequately examined this specific question—the threat of infringement in the U.S.—and X had not yet had a full opportunity to present evidence on this particular factual nexus to the U.S., the Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for this point to be properly examined.

- The Court also suggested that if indirect jurisdiction for the U.S. court's injunction could be affirmed on remand, this might, in turn, support affirming indirect jurisdiction for the related damages award (potentially under rules for related claims, e.g., CCP Art. 3-6, by analogy).

Significance and Commentary Insights

This 2014 Supreme Court decision is important for several reasons:

- Clarification of Indirect Jurisdiction Standard: It reaffirmed that Japan employs a flexible approach to indirect jurisdiction, guided by its domestic jurisdictional rules but allowing for case-specific considerations based on jōri (reason) and the appropriateness of recognition, rather than a rigid "mirror image" of its direct jurisdiction rules.

- Scope of Tort Jurisdiction for Injunctions: The ruling significantly broadened the understanding of "place of tort" for establishing jurisdiction over claims for injunctive relief, extending it to cover locations where infringement is merely threatened. This is particularly relevant for intellectual property and trade secret cases where preventive remedies are sought.

- Consistent Standard of Proof: The decision confirmed that the "objective factual relationship" standard for proving jurisdictional facts—requiring proof of a concrete link rather than a full trial on the merits of the underlying claim—applies equally to determinations of both direct and indirect jurisdiction.

- Guidance for Trade Secret Cases: As the first Supreme Court ruling on indirect jurisdiction in a trade secret infringement context, it provides crucial guidance. Academic commentary suggests that for trade secrets, the place where they are primarily managed or where their value could be undermined by threatened disclosure or use would likely be relevant for establishing the "place where rights are threatened with infringement."

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2014 ruling in this trade secret enforcement case refines the framework for assessing indirect jurisdiction, a key step in the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments in Japan. It emphasizes a nuanced approach that, while rooted in Japan's domestic jurisdictional principles, allows for reasoned adjustments to ensure fairness and appropriateness in the international context. For parties seeking to enforce foreign judgments in Japan, especially those involving injunctive relief or threatened harm, this decision highlights the necessity of demonstrating a clear objective factual link—even if only a threat—connecting the defendant's conduct or its potential impact to the country that issued the original judgment.