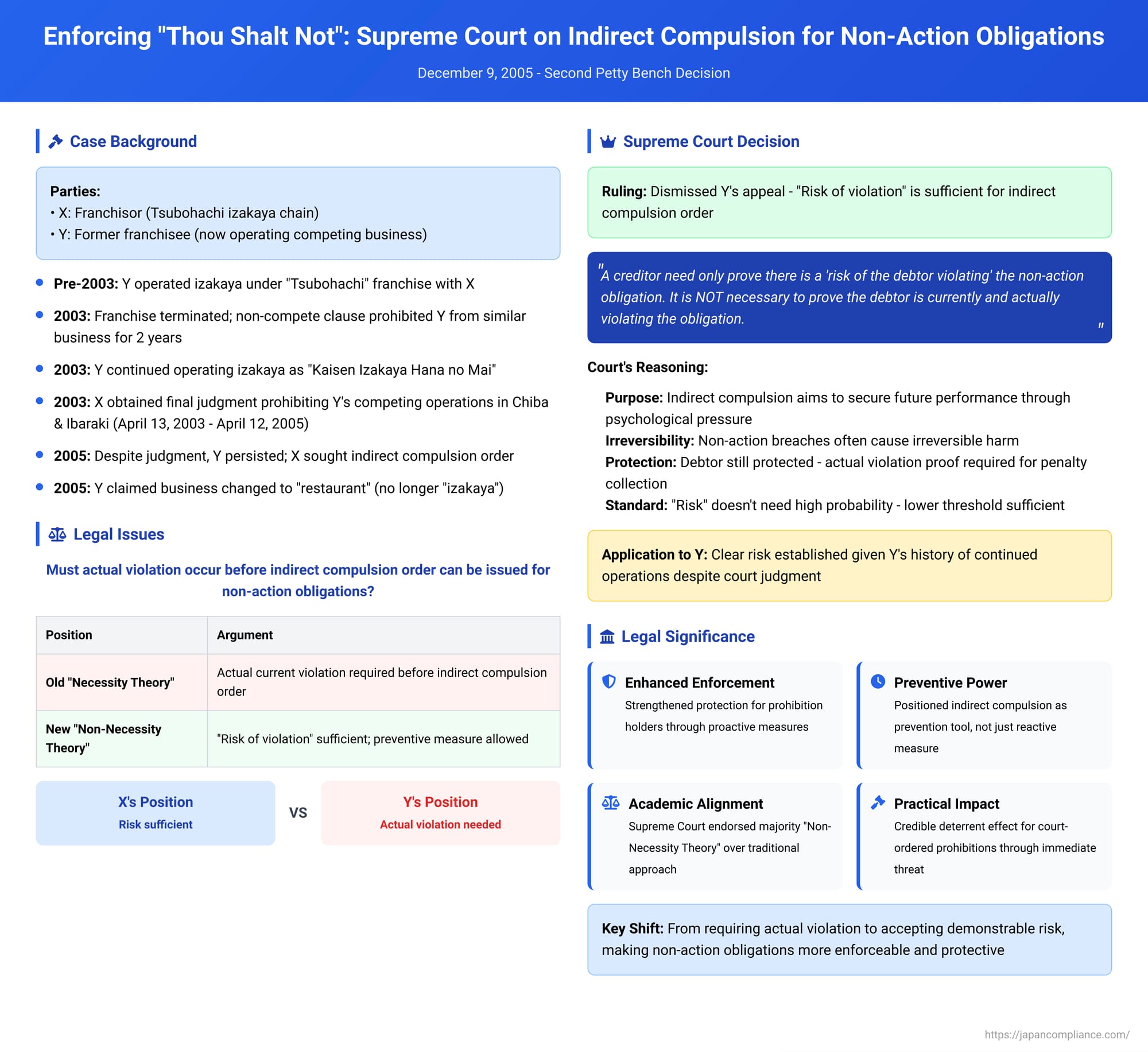

Enforcing "Thou Shalt Not": Supreme Court on Indirect Compulsion for Non-Action Obligations – A 2005 Japanese Case

Date of Decision: December 9, 2005

Case Name: Appeal Against Dismissal of Execution Appeal Against Indirect Compulsion Order (Permitted Appeal)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: 2005 (Kyo) No. 18

Introduction

When a court orders someone not to do something – for example, not to compete with a former business partner, not to infringe on a patent, or not to come near a certain place – this is known as a "non-action obligation" (不作為義務, furusakui gimu). Enforcing such prohibitions can be challenging. If the person simply ignores the court order and does the forbidden act, the harm might already be done and often cannot be easily undone.

One of the primary tools in Japanese civil execution law to enforce such non-action obligations is "indirect compulsion" (間接強制, kansetsu kyōsei). This involves the court prospectively ordering the debtor (the person subject to the prohibition) to pay a certain amount of money to the creditor for future violations, thereby creating a strong financial disincentive to breach the obligation. A critical question, however, has been: must a creditor wait for the debtor to actually violate the prohibition before they can ask the court to issue an indirect compulsion order? Or is the mere risk of a future violation sufficient? The Supreme Court of Japan provided a definitive answer to this in a key decision on December 9, 2005.

The Case of the Competing Izakayas: A Franchise Dispute

The facts leading to this Supreme Court decision were:

- X (Creditor/Respondent): The franchisor.

- Y (Debtor/Appellant): A former franchisee.

Y had operated several Japanese-style pubs (izakaya) under the well-known name "Tsubohachi" through a franchise agreement with X. After this agreement was terminated, Y continued to operate izakaya at the same locations but under a new name, "Kaisen Izakaya Hana no Mai" (Seafood Izakaya Hana no Mai).

The original franchise agreement contained a non-compete clause that prohibited Y from engaging in similar business operations for two years following the termination of the contract. X sued Y, alleging a breach of this non-compete clause and seeking an injunction to stop Y's competing izakaya business. X was successful in this lawsuit, obtaining a final and binding judgment that prohibited Y from operating izakaya or similar businesses in Chiba and Ibaraki prefectures for a two-year period (from April 13, 2003, to April 12, 2005).

Despite this clear judgment, Y continued to operate its izakaya establishments. Consequently, on February 23, 2005 (within the prohibition period), X applied to the execution court for an indirect compulsion order based on the existing judgment. X sought to compel Y's compliance with the non-action obligation.

In response to X's application, Y argued that as of March 1, 2005, it had changed its business operations. Y claimed the establishments were now "Kaisen Restaurant Hana no Mai" (Seafood Restaurant Hana no Mai), with new signage and a completely revamped menu, implying that it was no longer operating an "izakaya" or a "similar business" and therefore was not in violation of the court's injunction.

Lower Court Rulings on Indirect Compulsion:

- The court of first instance (Tokyo District Court), acting as the execution court, sided with X. It issued an indirect compulsion order stating that if Y violated the non-action obligation stipulated in the judgment, Y must pay X JPY 100,000 per day, per violating store.

- Y filed an "execution appeal" (執行抗告, shikkō kōkoku) against this order. The High Court (Tokyo High Court) dismissed Y's appeal. Critically, the High Court held that when issuing an indirect compulsion order based on a title of obligation for non-action, the actual current existence of a violation by the debtor is not a prerequisite for the order.

Y then sought and was granted permission to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling: "Risk of Violation" is Sufficient

The Supreme Court, in its decision on December 9, 2005, dismissed Y's appeal and upheld the High Court's stance. It laid down a clear rule for issuing indirect compulsion orders for non-action obligations:

A creditor seeking an indirect compulsion order under Civil Execution Act Article 172(1) to enforce a non-action obligation need only prove that there is a "risk of the debtor violating" (違反するおそれ, ihan suru osore) that obligation. It is NOT necessary for the creditor to prove that the debtor is currently and actually violating the non-action obligation at the time the indirect compulsion order is sought.

The Supreme Court provided several reasons for this conclusion:

- Purpose of Indirect Compulsion: The fundamental aim of indirect compulsion is to psychologically pressure the debtor into complying with their obligation and thereby secure future performance. It achieves this by prospectively ordering a monetary payment conditional on non-performance. If an actual violation had to occur before such an order could be issued, the preventive and future-compliance-oriented purpose of indirect compulsion could not be adequately fulfilled.

- Irreversible Nature of Non-Action Breaches: Claims for non-action (i.e., demanding that someone refrain from doing something) are inherently difficult, often impossible, to remedy satisfactorily after a breach has occurred. Once the forbidden act is done, the damage may be irreversible. If a creditor had to suffer at least one instance of violation before being able to seek an indirect compulsion order, the effectiveness of their adjudicated right to non-action would be severely compromised.

- Sufficient Debtor Protection Exists: The Court addressed concerns about debtor protection. It pointed out that an indirect compulsion order itself merely sets the stage for a potential payment. To actually collect the monetary penalty stipulated in the indirect compulsion order, the creditor must take a further step: they need to obtain an "execution clause" (執行文の付与, shikkōbun no fuyo) from the court clerk (Civil Execution Act Arts. 27(1), 33(1)). To obtain this execution clause for collecting the penalty, the creditor will then have to prove that the debtor has indeed violated the non-action obligation after the indirect compulsion order was in effect. Since proof of actual violation is required at the penalty collection stage, not requiring it at the initial order issuance stage does not leave the debtor without protection against unwarranted collection.

- "Risk of Violation" is Still Necessary: While an actual violation isn't a prerequisite for the order, the Court also stated that an indirect compulsion order is unnecessary if there is no "risk of the debtor violating the non-action obligation" at all. Therefore, the creditor does bear the burden of proving this "risk of violation."

- Degree of "Risk" Required: Importantly, the Supreme Court clarified that this "risk of violation" does not need to be established to a "high degree of probability or urgency." A lower threshold of demonstrating such a risk is sufficient.

- Application to Y's Case: In the specific facts of Y's case, the Supreme Court found it evident that this (less stringent) requirement of a "risk of violation" was clearly met, given Y's history of non-compliance with the original judgment.

The Legal Evolution: From "Actual Violation Needed" to "Risk is Enough"

The Supreme Court's 2005 decision was a significant milestone, effectively settling a long-standing debate in Japanese execution law regarding non-action obligations.

- The Old "Necessity Theory" (必要説, hitsuyō-setsu): For many years, the prevailing view among scholars and in some court practices was that an indirect compulsion order could only be issued if there was a current, actual violation of the non-action obligation by the debtor.

- If no violation had occurred since the judgment ordering non-action, it was argued that the obligation was either not yet "due" for enforcement (in the case of a prohibition tied to a specific future point) or was currently being complied with (for ongoing prohibitions).

- Even if there had been past violations, if they had ceased, some argued there was no present non-performance to justify current indirect compulsion.

- (Some proponents of this view did allow for alternative remedies, like a monetary order for "suitable measures for the future" under the old Civil Code, which had a similar effect to indirect compulsion in cases of past, but not necessarily ongoing, breaches of continuous non-action obligations.)

- The Rise of the "Non-Necessity Theory" (不要説, fuyō-setsu): Professor Takeshita Morio was a leading voice challenging the "Necessity Theory." He argued that indirect compulsion should be available as a preventive measure, even before an actual violation occurs. This "Non-Necessity Theory" gained significant traction and became the majority academic view over time. Its rationales included:

- The often irreversible nature of harm from breaches of non-action obligations.

- The inadequacy of forcing creditors to wait for a violation before seeking effective enforcement.

- Comparative law insights (French and German systems allowed for preventive use of similar mechanisms).

- The policy argument that allowing execution before an obligation is "due" (in the traditional sense) is permissible if it serves the ends of justice.

- The Supreme Court's 2005 Endorsement: This decision firmly aligns the Supreme Court with the "Non-Necessity Theory." By stating that an actual current violation is not required, and that the purpose of indirect compulsion is future compliance, the Court adopted the core tenets of this modern approach. The ruling seems broadly applicable to situations where no violation has yet occurred post-judgment, as well as to cases (like Y's) where there's a history of non-compliance suggesting a continuing risk. A 1991 Tokyo High Court decision had already signaled a shift in practice towards this theory.

Defining the "Risk of Violation"

While clarifying that an actual violation is not needed, the Supreme Court did mandate proof of a "risk of violation," albeit not one of high probability or urgency. The precise nature and proof of this "risk" remain points of academic discussion:

- Pre-2005 Views on "Risk": Before this decision, those who considered "risk" often thought in terms of a "high degree of probability" or "imminent and clear danger" of violation.

- The 2005 Standard: The Supreme Court explicitly lowered this bar.

- Post-2005 Academic Perspectives:

- Many scholars now support the Supreme Court's stance: some demonstrable risk is necessary, but it's not a high threshold.

- A minority still argue that proving "risk of violation" at the indirect compulsion stage should be unnecessary, especially if the original judgment or injunction (the "title of obligation") was granted precisely because such a risk was already established or inherent in the situation.

- Another nuanced view suggests a case-by-case approach: if the title of obligation is a judgment after a full trial on, say, a non-compete clause (as here), perhaps some fresh showing of risk is appropriate. If it's an injunction based on a statutory prohibition or a provisional disposition granted due to urgency, the initial finding of necessity might suffice without further proof of risk for the indirect compulsion order.

The "risk of violation" likely serves as a practical filter to prevent purely speculative or unnecessary applications for indirect compulsion, ensuring there's a genuine need for the court's coercive intervention. In Y's case, with a history of operating a similar business despite a judgment, establishing such a risk was straightforward.

Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's 2005 decision has significant implications:

- Enhanced Enforcement of Prohibitions: It makes it easier for holders of judgments or orders for non-action (e.g., non-compete clauses, intellectual property non-infringement orders, certain types of restraining orders) to proactively seek indirect compulsion orders to deter future violations.

- Preventive Power: It clearly positions indirect compulsion as a tool not just for reacting to breaches, but for preventing them by establishing a clear financial consequence before a violation occurs, based on a demonstrated risk.

- Alignment with Provisional Dispositions: The principles are generally considered applicable to the enforcement of provisional dispositions (仮処分, karishobun) ordering non-action as well.

Conclusion: Strengthening Prohibitive Orders Through Proactive Enforcement

The December 9, 2005, Supreme Court decision marks an important development in Japanese civil execution law. By confirming that an actual, ongoing violation is not a prerequisite for issuing an indirect compulsion order to enforce a non-action obligation, and by setting a realistic standard for proving the necessary "risk of violation," the Court has significantly strengthened the practical enforceability of prohibitive court orders. This approach allows creditors to act more preemptively to protect their rights, ensuring that court-ordered "thou shalt nots" carry a more immediate and credible deterrent effect, thereby better achieving the goal of future compliance.