Enforcing Provisional Injunctions in Japan: Validity of Shareholder Resolutions Passed in Violation

TL;DR: A 2024 Osaka High Court decision confirmed that a shareholder resolution passed in breach of a provisional injunction is void. The ruling tightens corporate-governance risk for issuers that ignore injunctions and clarifies the evidentiary burden when disputes escalate to nullification suits.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Background: Injunctions and Defective Resolutions in Japan

- The Shizuoka Case (May 20 2024): Facts and Ruling

- Analyzing the Shizuoka Decision in the Context of Legal Debate

- Implications for Corporate Practice and Litigation

- Conclusion

Introduction

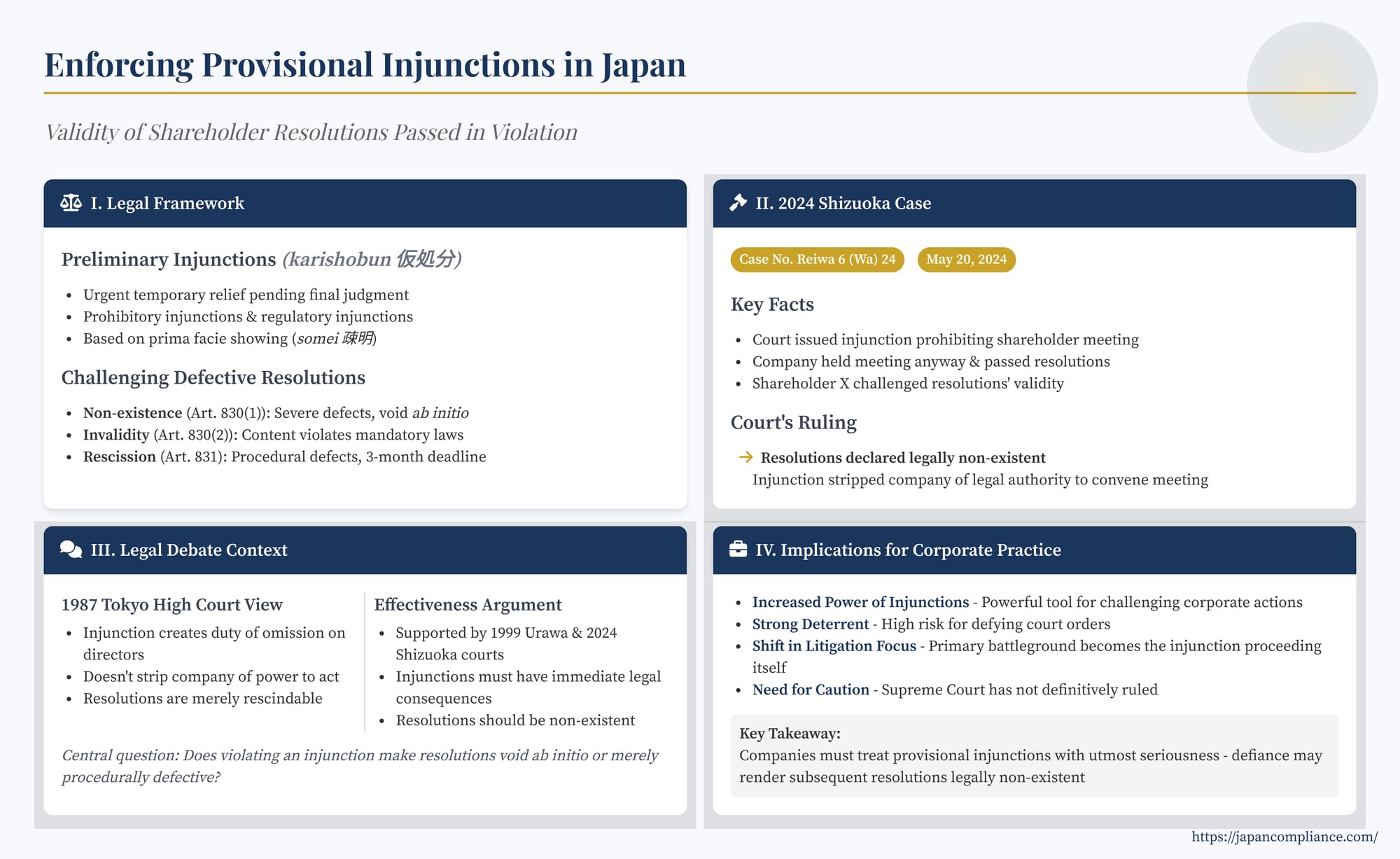

Court orders, including preliminary injunctions designed to provide urgent temporary relief, are fundamental tools for maintaining legal order and protecting rights during litigation. But what happens when a party, particularly a corporation, defies such an order? Specifically, if a Japanese court issues a preliminary injunction prohibiting a company from holding a shareholder meeting, and the company proceeds with the meeting anyway, are the resolutions passed at that meeting legally valid?

This question delves into a complex and contested area of Japanese corporate law, touching upon the power of provisional remedies, the sanctity of corporate decision-making processes, and the mechanisms for challenging defective resolutions. A recent decision by the Shizuoka District Court, Hamamatsu Branch, on May 20, 2024 (Case No. Reiwa 6 (Wa) 24), has brought this issue back into focus, offering a strong stance on the consequences of violating such injunctions.

This article examines the legal framework surrounding preliminary injunctions (karishobun) and defective shareholder resolutions in Japan. It analyzes the facts and ruling of the significant May 2024 Shizuoka case, places it within the context of a long-standing legal debate, and discusses the practical implications for companies, shareholders, and corporate litigation strategy in Japan.

1. Background: Injunctions and Defective Resolutions in Japan

Understanding the Shizuoka court's decision requires familiarity with two key areas of Japanese law: provisional remedies and challenges to shareholder resolutions.

- Preliminary Injunctions (Karishobun 仮処分): Governed by the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (Minji Hozen Hou), karishobun are court orders intended to provide swift, temporary protection of rights or legal positions pending a final judgment on the merits. They are granted based on a prima facie showing (somei 疎明) of the underlying right and the necessity for provisional relief (e.g., to prevent irreparable harm). Relevant types include:

- Prohibitory Injunctions: Ordering a party not to do something (e.g., prohibiting the holding of a specific shareholder meeting).

- Regulatory Injunctions (Miman-teki Karishobun): Temporarily regulating a legal relationship or establishing a temporary legal status. The Shizuoka court characterized the injunction prohibiting the meeting as belonging to this category, arguing it temporarily altered the company's legal capacity to hold the meeting.

- Challenging Defective Shareholder Resolutions: The Japanese Companies Act (Kaishahou 会社法) provides several ways to challenge flawed shareholder resolutions, depending on the nature and severity of the defect:

- Action for Declaration of Non-existence (Ketsugi Fusonzai Kakunin no Uttae, Art. 830(1)): Used for resolutions with extremely severe procedural or substantive defects, essentially meaning no legally recognizable resolution ever came into being (e.g., the meeting was never actually convened, the resolution's content is physically impossible). Such resolutions are void ab initio (from the beginning), and the defect can be asserted by anyone at any time.

- Action for Declaration of Invalidity (Ketsugi Mukou Kakunin no Uttae, Art. 830(2)): Used when the content of a resolution violates mandatory laws or public policy. These resolutions are also void ab initio, and the defect can generally be asserted by anyone at any time.

- Action for Rescission (Ketsugi Torikeshi no Uttae, Art. 831): Used for less severe defects, primarily procedural irregularities (e.g., improper notice, unlawful resolution method, significantly unfair resolution process) or violations of the articles of incorporation. Critically, rescission requires a lawsuit filed by specific interested parties (shareholders, directors, etc.) within three months of the resolution date. If the court rescinds the resolution, it becomes invalid, generally prospectively.

The Core Question: When a company holds a shareholder meeting and passes resolutions in direct violation of a court injunction prohibiting that meeting, which category applies? Is the violation so fundamental that the resolutions are legally "non-existent" (a very strong finding)? Or is the violation merely a procedural defect that makes the resolutions potentially "rescindable" if challenged promptly based on the underlying flaws that initially justified the injunction?

2. The Shizuoka Case (May 20, 2024): Facts and Ruling

This case presented the issue squarely before the Shizuoka District Court, Hamamatsu Branch.

- Factual Summary:

- Company Y is a stock company with a board of directors. Shareholder X was also a director.

- The representative director of Y called an extraordinary shareholder meeting for December 26, intending to dismiss X as a director and appoint a new director, B.

- X received the notice but believed the convocation procedure was flawed (allegedly lacking a proper board resolution authorizing the meeting call and providing insufficient notice period).

- On December 20, X applied to the court for a preliminary injunction (karishobun) prohibiting Company Y from holding the December 26 meeting.

- On December 25, the court granted the injunction (honken karishobun), explicitly forbidding the holding of the scheduled shareholder meeting.

- Despite the court order, Company Y proceeded to hold the shareholder meeting (honken kabunushi soukai) on December 26 as planned. Resolutions were passed dismissing director X and appointing director B (honken kaku ketsugi). These changes were subsequently registered.

- X filed a lawsuit, primarily seeking a declaration that the resolutions were non-existent (fusonzai) because they were passed at a meeting held in violation of the court's injunction. Alternatively, X sought rescission (torikeshi) based on the underlying procedural defects (lack of proper board resolution, insufficient notice). X also sought confirmation of their own continuing status as a director and B's lack of director status.

- The Court's Holding: The Shizuoka court ruled in favor of X on their primary claim, declaring the resolutions legally non-existent. The court's reasoning was direct and focused solely on the violation of the injunction:

- It characterized the injunction prohibiting the meeting as a type of regulatory injunction (miman-teki karishobun) that creates a temporary legal status.

- It held that the effect of this injunction was to temporarily strip the company of its legal authority or competence (ken-nou 権能) to hold the shareholder meeting.

- Therefore, any meeting held and any resolutions passed in defiance of that order were fundamentally flawed from the outset, lacking the necessary legal basis to exist.

- The court explicitly stated that this conclusion of non-existence was based solely on the violation of the injunction itself, independent of the underlying procedural defects X had originally alleged.

3. Analyzing the Shizuoka Decision in the Context of Legal Debate

The Shizuoka court's clear-cut ruling enters a long-standing and complex debate in Japanese legal circles regarding the effect of violating provisional injunctions in corporate matters.

- Historical View vs. The 1987 Tokyo High Court Precedent: Older case law (dating back to the Taisho and early Showa eras) generally tended to view resolutions passed in violation of prohibitory injunctions as invalid (mukou) or non-existent (fusonzai). However, a highly influential Tokyo High Court decision in 1987 (Judgment of Dec 23, 1987) introduced significant uncertainty. That court reasoned:

- The effect of an injunction should depend on the underlying right it aims to protect (hi-hozen kenri).

- If the underlying right is, for example, a shareholder's right to seek an injunction against illegal acts by directors (under Companies Act Art. 360), the resulting court injunction primarily imposes a duty of omission on the directors (i.e., don't hold the meeting).

- Violating this duty of omission, the 1987 court argued, doesn't automatically nullify the corporate act (the shareholder meeting resolution) itself, as the injunction doesn't necessarily strip the company as an entity of its inherent power to act, only restricts the directors' actions.

- Under this view, the resolution might still be challenged, but likely through a rescission action based on the original procedural flaws, not automatically declared non-existent due to the injunction violation alone.

- The Effectiveness Argument (Supporting Shizuoka/Urawa): The Shizuoka decision aligns with a subsequent Urawa District Court case (Judgment of Aug 6, 1999) and a significant stream of academic thought that prioritizes the effectiveness (jikkousei 実効性) of provisional remedies. The core argument is:

- If companies can ignore injunctions prohibiting meetings and pass resolutions that are merely rescindable (requiring a separate, timely lawsuit by specific parties), the injunction loses much of its practical meaning and protective power. The damage (e.g., wrongful dismissal of a director) might be done before a rescission suit concludes.

- Treating the injunction as temporarily suspending the company's power to hold the meeting (as the Shizuoka court did, characterizing it as a miman-teki karishobun) provides a strong deterrent against defiance and ensures the court's provisional order has immediate legal consequence for the validity of subsequent actions.

- The Proportionality/Due Process Argument (Supporting 1987 Tokyo High Court): The counterarguments emphasize principles of proportionality and due process:

- Provisional injunctions are granted based on a prima facie showing (somei), not full proof on the merits (shoumei 証明). Declaring a formal corporate resolution non-existent – a very drastic legal consequence – based solely on the violation of such a preliminary order seems disproportionate.

- It bypasses the specific procedural requirements and strict time limits (3 months) established by the Companies Act for rescission suits (Art. 831), which are designed to balance the need to correct defects with the need for legal stability in corporate affairs.

- The injunction legally binds the respondent(s) named in the order (typically the company and/or its directors). Arguably, their act of holding the meeting is wrongful, but this doesn't automatically negate the validity of the resolution passed by the shareholders as a corporate organ, provided the shareholders themselves acted properly at the meeting.

4. Implications for Corporate Practice and Litigation

The Shizuoka District Court's approach, if widely adopted or confirmed by higher courts, has significant practical implications:

- Increased Power of Injunctions: It dramatically increases the potency of preliminary injunctions prohibiting shareholder meetings. Obtaining such an injunction becomes a powerful tool for challenging proposed corporate actions based on procedural flaws.

- Strong Deterrent Against Defiance: The risk for a company of proceeding with a meeting in violation of an injunction becomes exceptionally high. If the resolutions are deemed non-existent, any actions taken based on them (e.g., dismissing directors, approving transactions) are void from the start, potentially leading to significant legal chaos and liability.

- Shift in Litigation Focus:

- For Plaintiffs: Success shifts from needing to win a later rescission suit based on underlying defects to simply proving the injunction was validly issued and violated. The primary battleground becomes the injunction proceeding itself.

- For Defendants (Companies): Vigorously opposing the injunction application or immediately appealing (hozen igi, hozen koukoku) a granted injunction becomes absolutely critical. Ignoring the order is not a viable strategy.

- Need for Caution: This ruling underscores the paramount importance for companies and their legal advisors in Japan to treat court-issued provisional injunctions with utmost seriousness.

- Remaining Uncertainty: It must be stressed that this is a District Court decision. The conflicting 1987 Tokyo High Court precedent remains, and the Supreme Court of Japan has not definitively ruled on this specific point in the context of the modern Companies Act and Civil Provisional Remedies Act. Legal commentators suggest exploring intermediate solutions, such as treating the violation as strong evidence of "significant unfairness" justifying rescission under Article 831, rather than automatic non-existence.

Conclusion

The May 2024 Shizuoka District Court decision declaring shareholder resolutions passed in violation of a prohibitory injunction legally non-existent represents a significant development in Japanese corporate litigation practice. By prioritizing the effectiveness of provisional court orders and holding that such injunctions temporarily strip the company of the power to convene, the court adopted a stance that provides strong protection for parties obtaining such relief but potentially raises concerns about proportionality.

This ruling directly confronts the uncertainty created by the earlier 1987 Tokyo High Court decision and aligns with a theoretical perspective emphasizing the need for court orders to have practical teeth. While the final word from higher courts is awaited, this case sends a clear signal about the serious legal consequences of defying judicial injunctions in corporate disputes.

For businesses operating in Japan and their legal counsel, the key takeaway is the critical importance of respecting provisional court orders. The risks of proceeding in defiance of an injunction prohibiting a shareholder meeting appear to be substantially heightened following the Shizuoka court's reasoning. This area of law warrants close attention as further case law develops.

- Share-Transfer Restrictions in Closely-Held Japanese Corporations: Analysing Recent Case Law

- Commitment Procedures in Japanese Antitrust: Recent Trends and Implications for Tech Platforms

- Derivative vs. Original Acquisition of Rights in Japan: Key Differences for U.S. Investors

- Ministry of Justice — Q&A on Shareholder Litigation and Provisional Relief (JP)

https://www.moj.go.jp/MINJI/minji07_00160.html