Enforcing Non-Dischargeable Claims in Japan: Supreme Court Clarifies Procedural Path

Date of Judgment: April 24, 2014 (Heisei 26)

Case Name: Lawsuit for Grant of a Writ of Execution

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

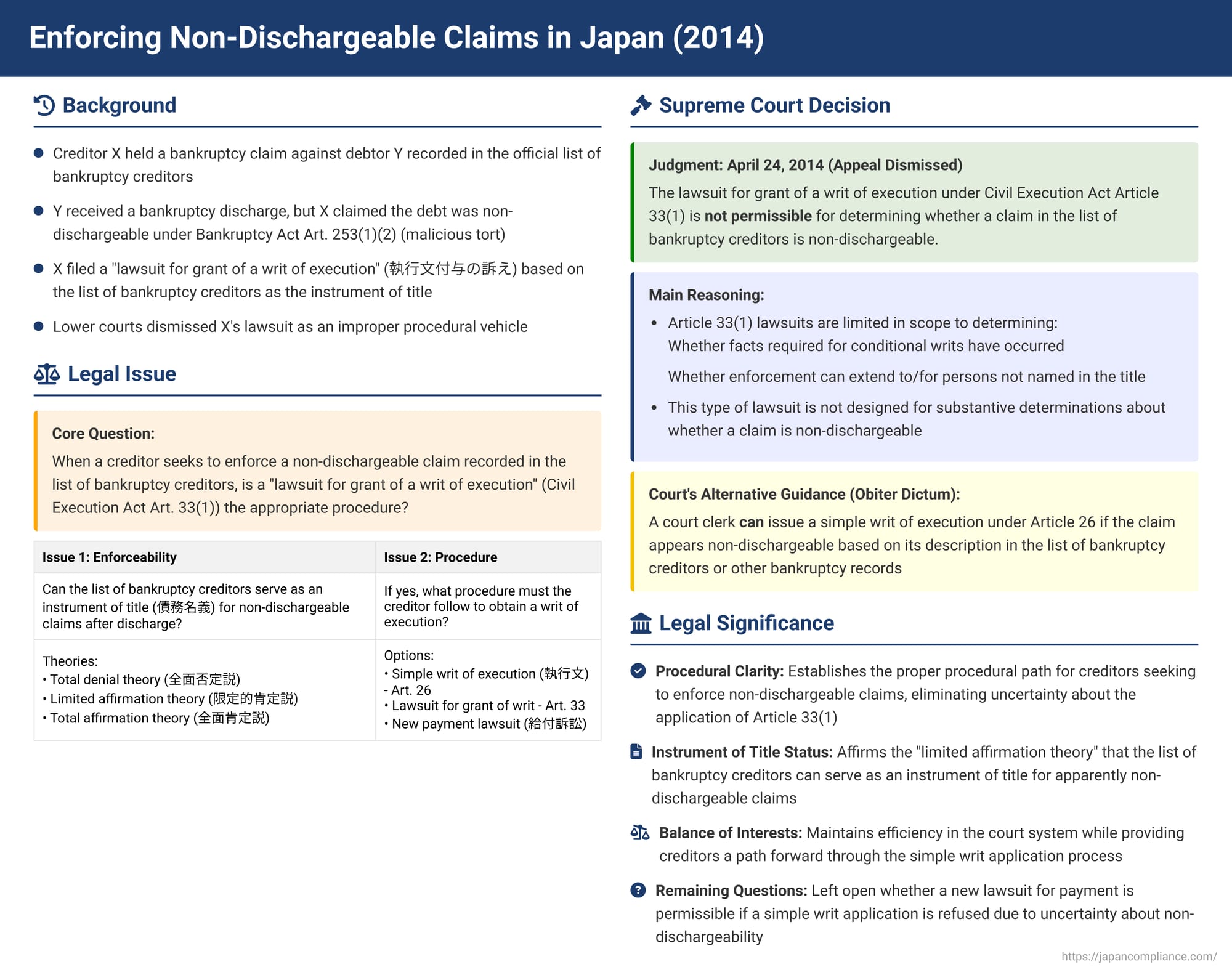

This blog post examines a 2014 Supreme Court of Japan decision that addressed a critical procedural question for creditors: after a debtor has received a bankruptcy discharge, how can a creditor enforce a claim that is considered "non-dischargeable" under the Bankruptcy Act, using the official "list of bankruptcy creditors" as the basis for enforcement? Specifically, the Court ruled on the permissibility of filing a "lawsuit for grant of a writ of execution" for this purpose.

Facts of the Case

The case involved a bankrupt individual, Y (the defendant/appellee), who had received a final decision terminating bankruptcy proceedings and a final decision granting discharge from debts. Creditor X (the plaintiff/appellant) held an established bankruptcy claim against Y, which was duly recorded in the official list of bankruptcy creditors (破産債権者表 - hasan saikensha-hyō). This claim consisted of a right of subrogation and a claim for damages arising from a tort. X asserted that this bankruptcy claim was non-dischargeable under Article 253, Paragraph 1, Item 2 of the Bankruptcy Act (which typically covers claims for damages from torts committed by the bankrupt with malicious intent).

Based on this assertion, X filed a "lawsuit for grant of a writ of execution" (執行文付与の訴え - shikkōbun fuyo no uttae) against Y, seeking a writ of execution based on the aforementioned list of bankruptcy creditors as the instrument of title. The bankruptcy trustee for Y had previously acknowledged parts of X's claim during the claims investigation period, leading to its inclusion in the list.

Lower Court Rulings

Both the court of first instance and the High Court ruled that X's lawsuit for grant of a writ of execution was improper and should be dismissed. Their reasoning centered on two main points:

- The type of writ of execution X would require in this situation would be a "conditional writ" (specifically, a "condition fulfillment execution writ" - 条件成就執行文) under Article 27, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Execution Act. This provision, they reasoned, pertains to the occurrence of a specific future event. However, X's assertion that the claim was non-dischargeable due to Y's "malicious intent" (悪意 - akui) related to circumstances at the time of the tort or when the claim arose – i.e., events prior to the creation of the instrument of title (the list of bankruptcy creditors). Therefore, it did not concern the "arrival of a future fact" as contemplated by Article 27(1).

- X had alternative means to enforce the claim if it was indeed non-dischargeable. For example, X could potentially obtain a simple writ of execution under Article 26, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Execution Act, or X could file a new lawsuit against Y specifically seeking payment of the non-dischargeable claim.

X filed a petition for acceptance of appeal to the Supreme Court, arguing that a lawsuit for grant of a writ of execution under Article 33 of the Civil Execution Act should be permissible in this situation, either by direct application or by analogy.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' dismissal of the lawsuit for grant of a writ of execution .

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Scope of a Lawsuit for Grant of a Writ of Execution (Civil Execution Act Article 33, Paragraph 1):

The Court stated that, based on the wording of Article 33, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Execution Act, the scope of matters that can be tried in such a lawsuit is limited. It is confined to determining:- Whether a fact that the creditor must prove for a conditional writ of execution (e.g., under Article 27) has indeed occurred.

- Whether enforcement can be carried out against or for a person not explicitly named as a party in the instrument of title (e.g., a successor in interest).

The Court concluded that this type of lawsuit is not intended for determining whether an established bankruptcy claim recorded in the list of bankruptcy creditors qualifies as a non-dischargeable claim (citing a 1977 Supreme Court precedent, Minshu Vol. 31, No. 6, p. 943).

- Alternative Available to the Creditor (Obiter Dictum):

The Supreme Court offered an alternative path for creditors in obiter dictum (a non-binding judicial comment). It stated that even if the list of bankruptcy creditors notes that a discharge decision has become final, the court clerk of the court where the bankruptcy records are held can still issue a simple writ of execution under Article 26 of the Civil Execution Act if the recorded bankruptcy claim, based on its description in the list or other content in the record, appears to be non-dischargeable. The Court suggested that, because this avenue exists, creditors holding such non-dischargeable claims would not suffer any particular hardship by disallowing the lawsuit under Article 33(1). - Conclusion:

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that it is not permissible for a creditor holding an established bankruptcy claim against a discharged debtor to file a lawsuit for grant of a writ of execution under Article 33(1) on the grounds that the claim is non-dischargeable, using the list of bankruptcy creditors as the instrument of title. The High Court's judgment, which reached the same conclusion, was affirmed .

Commentary and Elaboration

1. Significance and Positioning of the Decision

This Supreme Court decision primarily addresses the procedural question of how a creditor can obtain a writ of execution to enforce a non-dischargeable claim that is already recorded in the list of bankruptcy creditors, after the debtor has been discharged. To understand its significance, two related issues need consideration:

- (Issue 1) Enforceability: Can the list of bankruptcy creditors itself serve as an instrument of title (債務名義 - saimu meigi) for enforcing non-dischargeable claims after the debtor's discharge has become final?

- (Issue 2) Procedure: If it can serve as an instrument of title, what specific legal procedure must the creditor follow to obtain the necessary writ of execution?

The Supreme Court's judgment in this case:

- Affirms, albeit in obiter dictum, that the list of bankruptcy creditors can indeed serve as an instrument of title, at least for claims that appear to be non-dischargeable based on the record (this is known as the "limited affirmation theory" - 限定的肯定説 genteiteki kōtei-setsu).

- Clarifies (as its primary holding) that the procedural route for obtaining the writ of execution in such cases is an application for a simple writ of execution under Civil Execution Act Article 26, Paragraph 1, and not a lawsuit for grant of a writ of execution under Article 33, Paragraph 1.

2. Enforceability of the List of Bankruptcy Creditors Post-Discharge

The Supreme Court's statement that a court clerk can issue a simple writ of execution under Article 26 if the recorded claim "based on its description in the list or other record content, appears to be non-dischargeable" signals its endorsement of the limited affirmation theory. This means the list of bankruptcy creditors retains its character as an instrument of title, but its enforceability post-discharge is limited to those claims identifiable as non-dischargeable from the bankruptcy record itself.

This stance implicitly rejects a "total denial theory" (全面否定説 - zenmen hitei-setsu), which would argue that the list loses all its enforceability once a discharge decision becomes final. A "total affirmation theory" (allowing the list to be a valid title for all listed claims, leaving it to the discharged debtor to file an objection lawsuit if a claim was actually discharged) was likely not adopted because it would contradict the purpose of Article 26 (which presumes the issuing authority, the court clerk, checks if the instrument of title has lost its effect or if its enforceability has been excluded) and would unfairly burden the discharged debtor with initiating litigation to assert their discharge.

A practical challenge with the limited affirmation theory, however, is the extent to which a court clerk can accurately determine non-dischargeability. For some categories of non-dischargeable claims, such as those under Bankruptcy Act Article 253, Paragraph 1, Items 2 (malicious torts), 3 (certain personal injury torts), and 6 (certain fines/penalties), determining their status requires specific factual findings and legal evaluation, which may be beyond the scope of a clerk's summary review. Nevertheless, it is believed that in a fair number of cases, the non-dischargeable nature of a claim might be reasonably ascertainable from the description in the list of bankruptcy creditors, the case records, or other reference materials. This offers a relatively convenient, albeit limited, path for creditors. If the clerk cannot determine non-dischargeability from the record, an application for a simple writ of execution would be refused. This then leads to the question of what further steps a creditor can take.

3. The Appropriate Method for Obtaining a Writ of Execution

If an application for a simple writ of execution is refused by the court clerk, one available recourse is to file an objection to the disposition concerning the grant of a writ of execution under Civil Execution Act Article 32, Paragraph 1. This procedure is available for refusals of both simple and special (e.g., conditional) writs.

However, given that determining non-dischargeability can involve detailed factual and legal assessments, a full lawsuit with oral hearings, ensuring the creditor an opportunity to present their case and evidence, might be more appropriate from a due process perspective. The question then becomes what type of lawsuit is permissible.

The Supreme Court, in this decision, ruled out the lawsuit for grant of a writ of execution under Article 33, Paragraph 1. Citing its 1977 precedent, the Court reiterated that this type of lawsuit is narrowly designed to adjudicate the existence of specific conditions required for special writs of execution, such as the fulfillment of a condition precedent (under Civil Execution Act Article 27) or the extension of enforceability to or for a third party not named in the original instrument of title. It is not intended for a substantive examination of whether a claim, like one confirmed in a list of bankruptcy creditors, is non-dischargeable. The High Court in the present case had also noted the difficulty in categorizing the issue of non-dischargeability as one of the typical conditions for a special writ; it aligns more with a determination of the claim's existence and fundamental character.

Some criticisms have been leveled against disallowing the Article 33(1) lawsuit for this purpose:

- It's argued that determining non-dischargeability is essentially about assessing whether the discharge decision has extinguished the claim's enforceability, which is arguably within the purview of an Article 33(1) lawsuit that deals with the current enforceability of a title.

- Such a lawsuit could provide a quicker and less costly remedy within the bankruptcy court, which already possesses the relevant records.

- If the debtor did not contest the potentially non-dischargeable nature of the claim when it was filed in the bankruptcy proceedings, it might be reasonable to allow the creditor a simpler path to enforcement later via an Article 33(1) lawsuit.

Counterarguments supporting the Supreme Court's position include:

- The existing framework, where the court clerk can make an initial assessment for a simple writ (Art. 26), with subsequent disputes potentially resolved through other litigation where the burden of proof is appropriately allocated, is more consistent with the overall structure of the Civil Execution Act.

- The complexity of determining non-dischargeability would likely persist even in an Article 33(1) lawsuit, so it wouldn't necessarily offer a significantly faster resolution than, for example, a new lawsuit for payment.

4. Remaining Question: A New Lawsuit for Payment of the Non-Dischargeable Claim?

If the court clerk refuses to issue a simple writ of execution, and an Article 33(1) lawsuit is not permissible, can the creditor file a new lawsuit specifically seeking payment of the non-dischargeable claim (a 給付訴訟 - kyūfu soshō)? The Supreme Court's decision did not directly address this point.

Commentators suggest that such a new lawsuit for payment should be permissible. This is especially relevant when the non-dischargeability of the claim is not easily ascertainable from the bankruptcy records alone, and when the creditor needs a full opportunity to present evidence and arguments. The mere existence of the claim in the list of bankruptcy creditors (which, for this specific purpose of obtaining a new judgment, might not be directly enforceable if a simple writ is denied) should not preclude a new lawsuit due to a supposed lack of "interest to sue" (uttae no rieki). It is also argued that a creditor should be able to file such a new payment lawsuit even without first having to apply for a simple writ of execution and having it refused.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2014 decision clarifies that a creditor seeking to enforce a non-dischargeable claim recorded in the list of bankruptcy creditors against a discharged debtor should first attempt to obtain a simple writ of execution from the court clerk. A "lawsuit for grant of a writ of execution" under Civil Execution Act Article 33(1) is not the proper procedure for determining the non-dischargeable nature of such a claim. While the decision affirms, in obiter dictum, the potential for the list of bankruptcy creditors to serve as an instrument of title for apparently non-dischargeable claims, it leaves open the question of whether a creditor, if a simple writ is denied, can initiate a new lawsuit for payment. This ruling underscores the specific procedural pathways and limitations creditors face when seeking to enforce claims that survive a debtor's bankruptcy discharge in Japan.