Enforcing Judgments Against "Associations Without Legal Personality" in Japan: Navigating Real Estate Execution

In Japan, an "association without legal personality" (権利能力のない社団 - kenri nōryoku no nai shadan) is a group that operates like a corporate body but lacks formal legal personality. While these associations can sue and be sued, they face a peculiar challenge regarding property ownership: they cannot be the registered owner of real estate. Instead, real property belonging to such an association is typically held in the "collective ownership" (sōyū) of all its members and is often registered in the name of the association's representative, a designated member, or, as highlighted in a key 2010 Supreme Court case, even an unrelated third party.

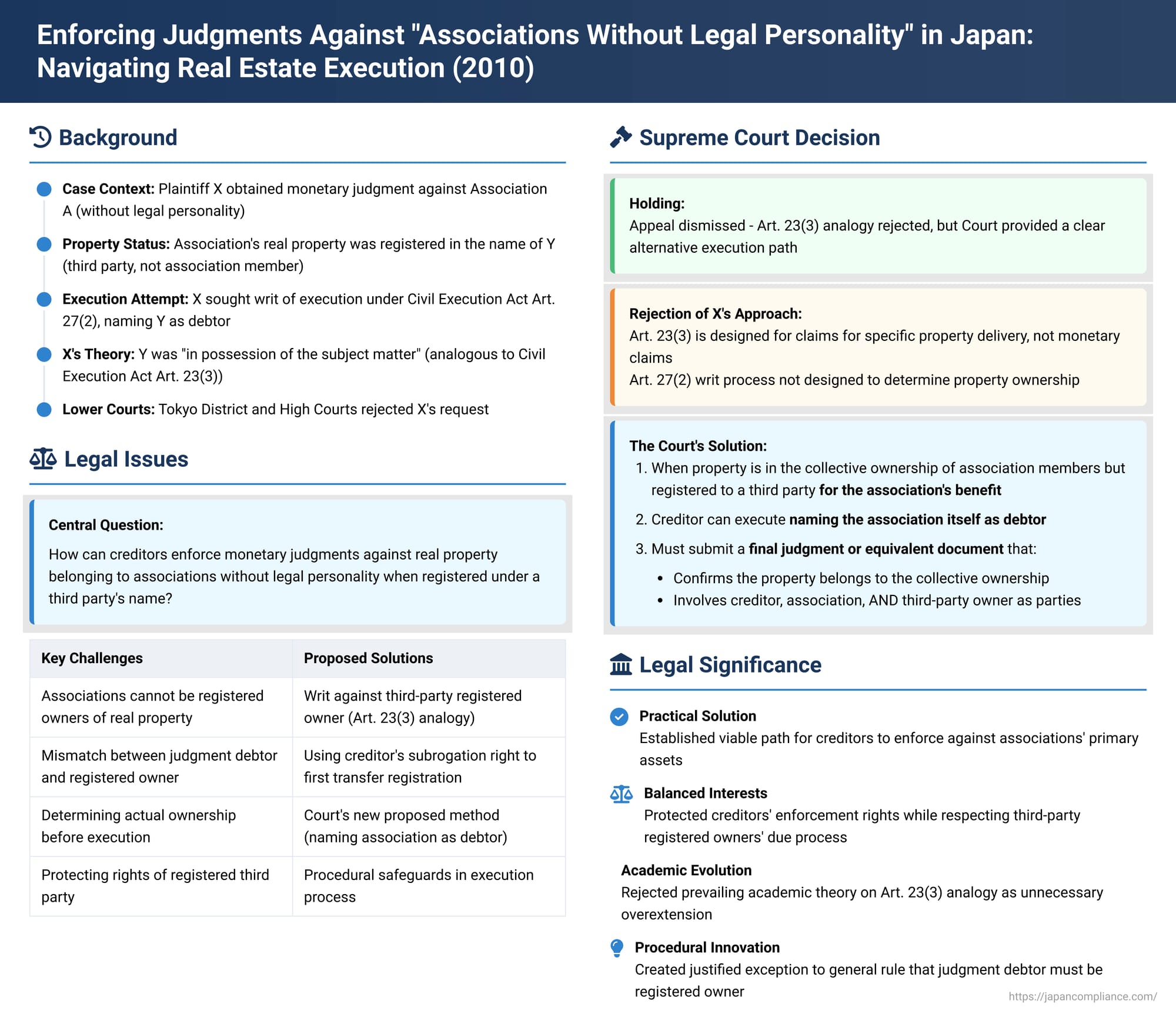

This arrangement creates significant hurdles for creditors who have obtained a monetary judgment against an association without legal personality and wish to enforce it against the association's real property. The core problem is the mismatch between the judgment debtor (the association) and the registered owner of the property. A Supreme Court decision on June 29, 2010 (Heisei 21 (Ju) No. 1298) provided crucial clarification on the proper method for such enforcement.

Background of the Dispute

The plaintiff, X, had obtained a monetary judgment (with a declaration of provisional execution) against Association A, an association without legal personality. X then sought to enforce this judgment against certain real property (the "Property") that was allegedly part of Association A's assets, meaning it was in the collective ownership of A's members. However, the Property was registered in the name of Y, a third party who was not a member or representative of Association A.

X's approach was to request a writ of execution under Article 27, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Execution Act, which allows a writ to be issued against a successor or a third party under certain conditions. X argued that Y should be named as the debtor in this writ, contending that Y was a person "in possession of the subject matter of the claim" akin to the scenario described in Article 23, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Execution Act (which generally applies to claims for the delivery of specific property held by a third party).

The Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court both rejected X's request for the writ of execution naming Y as the debtor. The High Court reasoned that while Article 23, Paragraph 3 might be extended by analogy if the association's property were registered in the name of its representative (in which case execution would be limited to that specific property), this was not the case here. Since the Property was registered in the name of an unrelated third party (Y), the High Court suggested that X could potentially use a creditor's subrogation right (under the Civil Code) to first compel the transfer of the property registration from Y to Association A's representative, and then levy execution. Because this alternative path was supposedly available, the High Court found no necessity to apply Article 23, Paragraph 3 by analogy. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, agreeing with the lower courts that issuing a writ of execution naming Y as the debtor under Article 27(2) (based on an analogy to Article 23(3)) was not the correct procedure for enforcing a monetary claim in this context.

1. Rejection of Analogical Application of Civil Execution Act Article 23(3) for Monetary Claims

The Court clarified that Article 23, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Execution Act is designed for situations involving the enforcement of claims for the delivery of specific objects or similar non-monetary claims where a third party is in possession of that object. It is not intended for the enforcement of general monetary claims against assets. Furthermore, the procedural framework for issuing a writ of execution under Article 27, Paragraph 2 (and the related action concerning such a writ) is not designed to substantively determine whether the property targeted for execution actually belongs to the judgment debtor (Association A in this case). Therefore, the Court held that broadly extending the application of Article 23, Paragraph 3 to allow a writ against the third-party registered owner (Y) for a monetary claim against the association was impermissible.

2. The Permissible Method for Execution Against the Association's Property

Despite rejecting X's specific request, the Supreme Court provided a clear pathway for creditors in such situations:

- The Challenge: The Court acknowledged the fundamental issue: an association without legal personality cannot be the registered owner of real property that is in the collective ownership of its members (citing a 1972 Supreme Court precedent). This means there will always be a discrepancy between the name of the judgment debtor (the association) and the name of the registered owner of the target real estate. If standard real estate execution procedures—which typically require the judgment debtor to be the registered owner—were strictly applied, it would effectively deny creditors the ability to enforce their rights against the association's primary assets. Such an interpretation, the Court stated, would be unreasonable.

- The Solution: The Supreme Court outlined the following method: When real property that is in the collective ownership of an association's members is registered in the name of a third party for the benefit of the association, a creditor holding a monetary judgment against the association can initiate compulsory execution proceedings by naming the association itself as the judgment debtor.

- Required Documentation for Execution Application: To proceed with this method, the creditor must submit, in addition to the standard writ of execution issued against the association:

- A final and binding judgment or an equivalent official document. This document must be between the creditor, the association without legal personality, AND the third-party registered owner (Y).

- This judgment or document must confirm that the specific real property belongs to the collective ownership of all members of the association.

The Court indicated this approach is analogous to the rules for executing against real property that is recorded in the land registry's "heading section" (i.e., unregistered as to specific ownership rights) as belonging to someone other than the judgment debtor (referencing Article 23, Item 1 of the Civil Execution Rules).

Justice Tahara's Supplementary Opinion

Justice Tahara, while concurring with the majority's outcome, provided a detailed supplementary opinion that further elaborated on the legal reasoning and practical implications. Key points from his opinion include:

- Rejection of the Previously Influential Academic Theory: For a long time, a prominent academic view suggested that Article 23(3) of the Civil Execution Act could be extended by analogy to allow a creditor to obtain a writ of execution against the registered owner (e.g., the association's representative) when enforcing a monetary claim against the association's collectively owned property. Justice Tahara argued that given the clear method now outlined by the Court's majority opinion, this extensive interpretation of Article 23(3) is no longer necessary or appropriate for practical application. Such an extension would significantly deviate from the original purpose of Article 23(3) and create an anomalous form of monetary execution where the named execution debtor is the registered owner rather than the association itself. This could lead to various complications, for example, if the personal creditors of the registered owner attempt to participate in the distribution of proceeds, it would be difficult to exclude them.

- Differentiating Scenarios Based on the Registered Owner's Identity:

- Scenario 1: Clear Link between Registered Owner and Association. If the real property is proven to be in the collective ownership of the association's members, and the registered owner is clearly linked to the association (e.g., the current representative, all members jointly, or a person designated by the association's articles of association, with this link evidenced by reliable documents like the judgment itself or notarized articles), then execution can proceed as if the registered owner and the judgment debtor (the association) were identical. In such cases, the registered owner is in a position where they must tolerate the execution. If the registered owner still disputes the association's ownership despite such clear evidence, it would not be unfair to place the burden on them to file a third-party objection to the execution.

- Scenario 2: Unclear Link between Registered Owner and Association. If the registered owner is, for example, a former representative, or a third party whose current connection to the association as the proper title holder is not immediately evident from existing documents, the situation is more complex. Ideally, the association (or its current representative or designated person) should first take steps to have the property registration transferred into the name of the current, appropriate representative. A creditor could initiate such a transfer through a creditor's subrogation action if the association fails to act. However, Justice Tahara suggested that even in this scenario, if the property is definitively proven to be in the collective ownership of the association's members, and this fact is also established with a high degree of proof concerning the registered owner's status (i.e., holding for the association), the execution court could recognize this connection and permit execution against the property, naming the association as the debtor. The burden would then fall on the registered owner to contest this through a third-party objection if they claim individual ownership.

- Evidentiary Documents: Justice Tahara listed examples of documents that could prove the collective ownership and the registered owner's status: a final declaratory judgment involving the creditor, association, and registered owner; a court settlement record; a notarial deed explicitly stating the property is in collective ownership; or the association's articles of association (if equivalent to a notarial deed in evidentiary value) that specify who should be the registered owner on behalf of the association.

- Provisional Remedies (e.g., Provisional Attachment): For pre-judgment attachment, if the link between the association and the registered owner is clear (Scenario 1), a creditor can apply for provisional attachment by proving the collective ownership of the property. If the link is unclear (Scenario 2), direct provisional attachment against the property naming the third-party registered owner might be difficult due to evidentiary challenges. In such cases, a creditor might find it more practical to seek a provisional disposition prohibiting the transfer of the property, pursued via a creditor's subrogation action.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

The 2010 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling that offers a practical and legally coherent solution to a long-standing problem in Japanese civil execution law.

- Clear Path for Creditors: It definitively establishes a method for creditors to enforce monetary judgments against the real property of associations without legal personality, even when that property is registered in the name of a third party. The key is to name the association itself as the debtor in the execution application and provide specific proof of collective ownership involving all relevant parties.

- Rejection of a Prevailing Academic Theory: The decision moves away from the previously influential academic theory that advocated for an analogical application of Article 23(3) of the Civil Execution Act and the issuance of a writ against the registered owner for monetary claims. The Court found this approach to be an overextension of the statutory provision and unnecessary given the alternative it endorsed.

- The "Confirmatory Judgment" Requirement: A cornerstone of the Court's solution is the requirement for a "final judgment or equivalent document" that confirms the property belongs to the collective ownership of the association's members and, importantly, involves the creditor, the association, and the third-party registered owner as parties. This requirement ensures that the registered owner's rights are considered and that they have had an opportunity to be heard on the issue of the property's true beneficial ownership before execution proceeds. It prevents the execution court from having to make a de novo substantive determination of ownership, thereby maintaining the separation between adjudicative and enforcement functions and promoting swift execution.

- Procedural Safeguards for the Registered Owner: While the execution proceeds with the association named as the debtor, the interests of the third-party registered owner are protected. The requirement for their involvement in the confirmatory judgment is the primary safeguard. Moreover, the Supreme Court's phrasing suggests that the third party must be holding the property "for the association," implying that if the third party holds it in their own right, this execution method would not apply.

- Consistency with General Execution Principles (with a Justified Exception): Generally, for real estate execution in Japan, the judgment debtor must be the registered owner. This decision carves out a specific, reasoned exception for associations without legal personality due to their inherent inability to hold registered title in their own name. The requirement for a prior confirmatory judgment bridges this gap by providing a judicial determination of the property's de facto ownership by the association.

- Handling Competing Claims: The PDF commentary further explores practical issues, such as how the court clerk can commission the necessary registrations for attachment and sale despite the mismatch between the debtor (association) and the registered owner. It also touches upon how to manage situations where the personal creditors of the third-party registered owner might attempt to execute against the same property. This would not typically result in a "double commencement of execution" under Article 47 of the Civil Execution Act because the underlying responsible entities are different. Instead, the execution by the registered owner's personal creditors would likely be stayed pending the outcome of the association's creditor's execution, unless a third-party objection by the registered owner (or their creditors via subrogation) against the association's creditor is successful.

- Provisional Attachment Simplified: It's noteworthy that a subsequent Supreme Court decision in 2011 clarified that for provisional attachment (a pre-judgment remedy) against such property, the stringent requirement of a final, binding judgment confirming collective ownership is not necessary. Instead, documents merely evidencing the fact of collective ownership are sufficient to support an application for provisional attachment naming the association as the debtor. This makes it easier for creditors to secure assets pending a final judgment on the merits of their monetary claim.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2010 decision provides a vital and pragmatic framework for the enforcement of monetary judgments against real property belonging to associations without legal personality in Japan. By rejecting a strained analogical application of existing statutes and instead requiring a confirmatory judgment of collective ownership involving all relevant parties, the Court balanced the need to provide effective remedies for creditors with the protection of the rights of third-party registered owners and the unique legal constraints surrounding property holding by these associations. This ruling brings much-needed clarity to a complex area of civil execution law, ensuring that the assets of such associations remain accessible to satisfy their debts while upholding due process.