Enforcing Foreign Judgments in Japan: Supreme Court Decodes Service, Appearance, and Jurisdiction

Date of Judgment: April 28, 1998

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

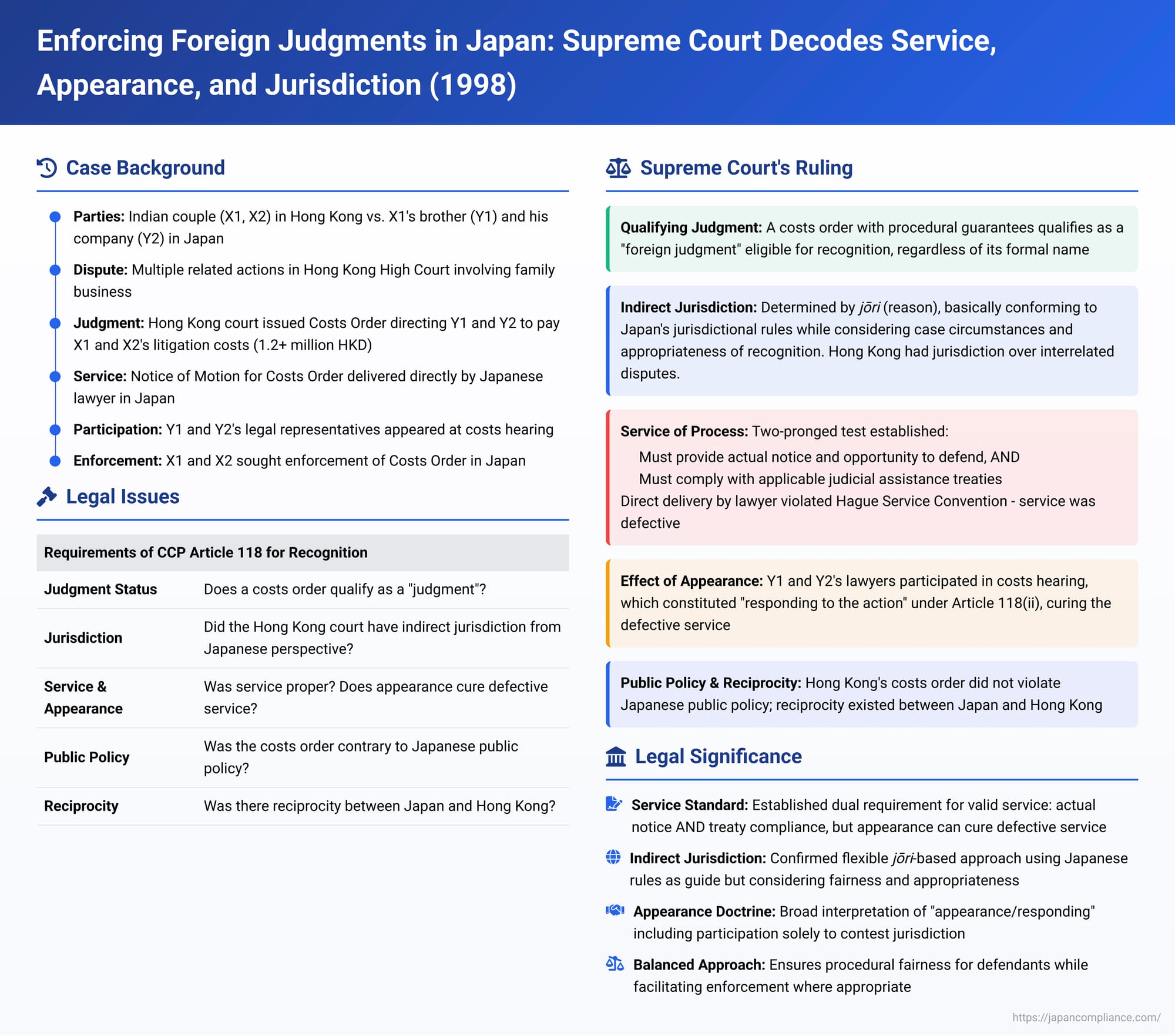

The ability to recognize and enforce judgments rendered by foreign courts is crucial for international commerce and comity. In Japan, Article 118 of the Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) lays down the conditions that a foreign judgment must meet to be recognized. A comprehensive Supreme Court decision on April 28, 1998, provided critical interpretations of several of these requirements, including what constitutes a "judgment," the concept of "indirect jurisdiction" of the foreign court, proper service of process, the effect of a defendant's appearance, and considerations of public policy and reciprocity. The case involved a complex family business dispute that spanned Hong Kong and Japan, culminating in a Hong Kong court order for litigation costs.

The Factual Background: A Family Business Dispute Spanning Hong Kong and Japan

The dispute arose from a series of intertwined legal actions:

- X1 and X2 (Plaintiffs): An Indian couple residing in Hong Kong.

- Y1 (Defendant): X1's brother, an Indian national residing in Japan.

- Y2 (Defendant Company): A Japanese company for which Y1 and his wife, A, served as directors.

- The Underlying Dispute: X1 and X2 had initially acted as guarantors, alongside Y1 and A, for a loan that Y2 company obtained from Z Bank. Following a family feud, Y1 allegedly arranged for a new guarantee agreement that excluded X1 and X2, and their original guarantee was purportedly cancelled. However, when Y2 company defaulted on the loan, Y1 and his associates reportedly entered into an agreement with Z Bank, leading Z Bank to sue X1 and X2 in the Hong Kong High Court to recover the guaranteed debt (Suit ①).

- Counter-Litigation in Hong Kong: In response to being sued, X1 and X2 initiated their own actions in Hong Kong. These included a claim against Z Bank, Y1, and A, seeking confirmation of their right to subrogation against a mortgage held by Y1 and A (Suit ②), and a third-party action against Y1, Y2, and A for indemnification (Suit ③). Y1, Y2, and A, in turn, filed a counter-action against X1 and X2, seeking a declaration that X1 and X2 alone were liable for the original guarantee debt (Suit ④).

- The Hong Kong Judgments: The Hong Kong High Court ultimately issued a substantive judgment in these related actions that was largely in favor of X1 and X2. This main judgment became final.

- The Costs Order ("Present Order"): Following the main judgment, upon X1 and X2's application, the Hong Kong High Court issued a detailed "Costs Order." This order, along with an integrated costs assessment certificate, directed Y1 and Y2 (and Z Bank, though the focus of the Japanese enforcement was on Y1 and Y2) to pay nearly all of X1 and X2's substantial litigation costs, amounting to over 1.2 million Hong Kong dollars.

- Service of the Motion for Costs: The "Notice of Motion" for this Costs Order was served on Y1 and Y2 in Japan through direct delivery by a Japanese lawyer privately retained by X1 and X2.

- Participation in Costs Hearing: Despite this method of service, legal representatives (Hong Kong solicitors) for Y1 and Y2 participated in the subsequent hearing for the Costs Order in Hong Kong.

- Enforcement Suit in Japan: After the Costs Order became final, X1 and X2 filed a lawsuit in the Kobe District Court in Japan, seeking an enforcement judgment to compel Y1 and Y2 to pay the amount stipulated in the Hong Kong Costs Order.

The Kobe District Court and the Osaka High Court both granted the enforcement judgment. Y1 and Y2 appealed to the Supreme Court, challenging the recognition of the Hong Kong Costs Order on multiple grounds under CCP Article 118.

The Supreme Court's Comprehensive Interpretation of Recognition Requirements (CCP Article 118)

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Y1 and Y2, thereby upholding the enforceability of the Hong Kong Costs Order in Japan. In doing so, it provided crucial interpretations of several conditions listed in CCP Article 118 (referring to the old CCP numbering, which largely corresponds to the current CCP Art. 118):

1. What Constitutes a "Foreign Court Judgment"? (Art. 118, introductory part; cf. Civil Execution Act Art. 24)

The Court clarified that a "foreign court judgment" eligible for recognition is not limited by its formal name (e.g., judgment, decree, order). It encompasses any final decision by a foreign court on private law relationships, provided it was rendered with procedural guarantees ensuring both parties were heard.

The Hong Kong Costs Order, which determined the liability for litigation costs following a hearing where Y1 and Y2 were represented, clearly fell within this definition.

2. Indirect Jurisdiction of the Foreign Court (Art. 118(i) - "jurisdiction is recognized by laws or treaties")

This condition requires that the foreign court (Hong Kong High Court) must have had international adjudicatory jurisdiction over the original case, as assessed from the perspective of Japanese private international law (this is "indirect jurisdiction" - 間接管轄, kansetsu kankatsu, or "recognition jurisdiction" - 承認管轄, shōnin kankatsu).

- Determined by Jōri (Reason): The Supreme Court reiterated its established stance that, in the absence of specific statutes or treaties directly governing indirect jurisdiction, it should be determined in accordance with "jōri" (reason, natural justice, or equity). This involves basically conforming to Japan's own Code of Civil Procedure rules on domestic territorial jurisdiction while also considering the specific circumstances of the individual case and the overall appropriateness of recognizing the foreign judgment.

- Ancillary Orders Follow Main Judgment: For an ancillary decision like a costs order, its indirect jurisdiction is, in principle, assessed based on whether the foreign court had jurisdiction over the main underlying substantive judgment(s).

- Hong Kong's Jurisdiction Affirmed: The Supreme Court found that the Hong Kong High Court did have indirect jurisdiction over the various underlying lawsuits based on Japanese jurisdictional principles applied by analogy (e.g., defendants' X1 & X2's domicile in Hong Kong for Suit ①, and jurisdiction over consolidated, closely related claims for the other suits, including Suit ③ which involved Y2 company). The need for unified adjudication of these interconnected claims supported finding Hong Kong's jurisdiction reasonable.

3. Service of Process and Defendant's Appearance (Art. 118(ii)) - A Core Part of the Ruling

This sub-clause requires that "the losing defendant has received service of a summons or order necessary for the commencement of the proceedings... or has responded to the action without receiving such service."

- Two-Pronged Test for Valid "Service" (送達 - sōtatsu) of Initiating Documents:

- Cognizance and Defense Possibility: The method of service, while not needing to strictly follow Japanese domestic procedures, must have been such that the defendant could actually become aware of the commencement of the proceedings and was not hindered in exercising their right to defend. This is a substantive test looking at the reality of notice and opportunity.

- Treaty Compliance: If a judicial assistance treaty concerning service of documents (司法共助 - shihō kyōjo) exists between Japan and the judgment-rendering country, and that treaty prescribes specific methods for service, then any service not complying with the treaty's prescribed methods is not considered valid service for the purposes of Article 118(ii).

- Application to the Service of the Costs Motion: The direct, private delivery of the Notice of Motion for the Costs Order to Y1 and Y2 in Japan by a Japanese lawyer was found to be defective service. The United Kingdom (then sovereign over Hong Kong) and Japan were both parties to the Hague Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters. Private direct delivery of this nature was not a method permitted by that Convention, nor by the bilateral Japan-UK Consular Convention. Thus, the "treaty compliance" prong was not met.

- Effect of "Appearance" or "Responding to the Action" (応訴 - ōso):

The Court clarified that "responding to the action" under Article 118(ii) is different from an appearance that might create jurisdiction by submission. For recognition purposes, it means that the defendant, having been given an opportunity to defend, actually took measures to defend themselves in the foreign court. This includes instances where the defendant appeared solely to contest the court's jurisdiction. - Application to Y1 and Y2's Conduct: Y1 and Y2, through their Hong Kong legal representatives, actively participated in the hearing for the Costs Order. The Supreme Court found this clearly constituted "responding to the action" under Article 118(ii).

- Conclusion on Art. 118(ii): Therefore, even though the initial service of the Notice of Motion for the Costs Order was deemed defective due to non-compliance with treaty methods, the subsequent appearance and participation by Y1 and Y2's lawyers in the costs hearing cured this defect, satisfying the requirements of Article 118(ii).

4. Public Policy (Art. 118(iii) - judgment's content not contrary to Japanese public order)

The Court found that ordering one party to bear all litigation costs, even if calculated on an "indemnity basis" (which in Hong Kong can include a fuller recovery of lawyer's fees, sometimes applied if a party's conduct was unreasonable), is not contrary to Japanese public policy (公の秩序 - kō no chitsujo) as long as the amount awarded does not exceed the expenses actually incurred. While the indemnity basis might have a punitive nuance, it wasn't seen as violating fundamental Japanese principles. Y1 and Y2's arguments that the main Hong Kong judgment was obtained by fraud were dismissed as attempts to re-litigate the merits of the evidence, which is not permissible in enforcement proceedings (cf. Civil Execution Act Art. 24(2)).

5. Reciprocity (Art. 118(iv) - mutual guarantee of recognition)

The Supreme Court affirmed that reciprocity (相互の保証 - sōgo no hoshō) existed between Japan and Hong Kong. Even though Japan was not on a specific statutory list of countries for reciprocal enforcement in Hong Kong, Hong Kong courts also recognized foreign judgments based on English common law principles. The Court found that these common law requirements for recognition were not substantially different from Japan's own requirements under Article 118.

Significance and Lasting Impact

This 1998 Supreme Court decision provided the first comprehensive judicial interpretation of several critical conditions for the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments in Japan under CCP Article 118.

- Dual Test for Valid International Service: A major clarification was the establishment of a two-pronged test for "service" under Article 118(ii): it must both (a) provide the defendant with actual knowledge and an opportunity to defend, AND (b) comply with any applicable international service treaties. This underscored the importance of adhering to formal international judicial assistance channels.

- Broad Interpretation of "Appearance/Responding": The ruling confirmed that a relatively broad range of defensive actions taken by a defendant in the foreign proceeding, including contesting jurisdiction, would be considered an "appearance" or "response" sufficient to cure initial defects in service for the purpose of satisfying Article 118(ii). This generally favors the recognition of foreign judgments where the defendant had engaged with the foreign court.

- Guidance on Indirect Jurisdiction: The Court reiterated its flexible jōri-based approach to assessing the foreign court's indirect jurisdiction, using Japanese domestic jurisdictional rules as a primary guide but allowing for case-specific considerations of fairness and the appropriateness of recognition.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1998 judgment in this complex international dispute provided a detailed and authoritative roadmap for navigating the requirements for recognizing and enforcing foreign judgments in Japan. It emphasized a balance: ensuring that defendants in foreign proceedings receive adequate procedural fairness (particularly regarding notice and the opportunity to defend, with due respect for international service conventions), while also facilitating the recognition of foreign judgments where such fairness has been afforded and where the foreign court properly exercised jurisdiction from a Japanese perspective. This case remains a crucial reference for parties involved in cross-border litigation and the subsequent enforcement of judgments in Japan.