Enforcing Foreign Judgments in Japan: A Landmark Supreme Court Decision Explained

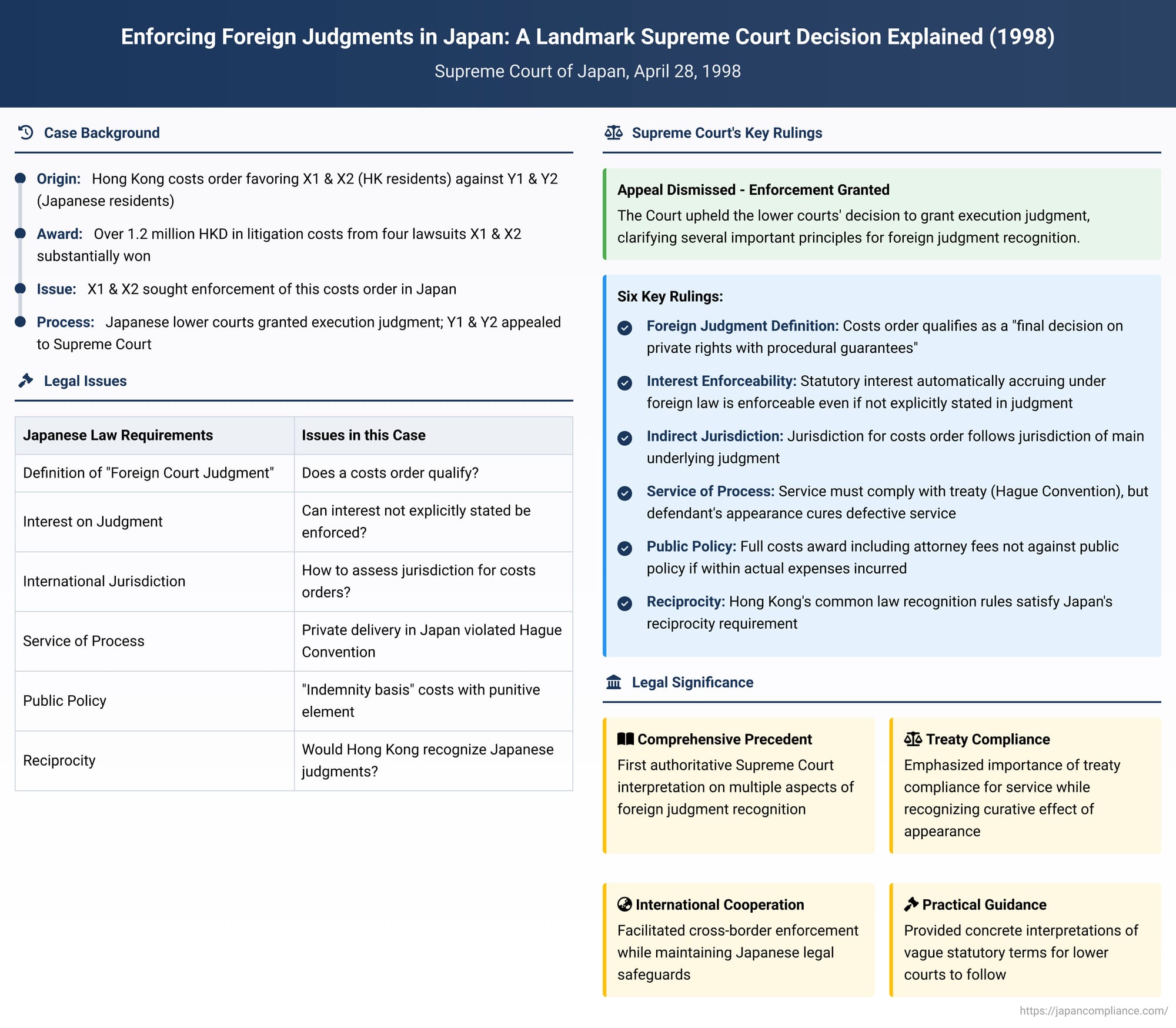

The recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments are critical aspects of international litigation and commerce. For parties who have obtained a favorable judgment in one country, the ability to have that judgment recognized and enforced in another jurisdiction where the debtor has assets is often paramount. In Japan, the conditions for such enforcement are laid out in the Code of Civil Procedure and the Civil Execution Act. A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on April 28, 1998, provided significant clarification on many of these requirements, becoming a leading authority in this field.

This article examines the Supreme Court's judgment in a case involving the enforcement of a Hong Kong court's order for litigation costs.

Case Background

The dispute originated from guarantees provided by X1 and his spouse X2, both Hong Kong residents, for loans extended by an Indian bank (Bank A) to Y1 (a resident of Japan) and Y2 (a Japanese company where Y1 and his spouse B were directors). All individuals involved were Indian nationals. A series of four lawsuits concerning these guarantees were initiated by Bank A against X1 and X2 in Hong Kong, all of which X1 and X2 substantially won.

Subsequently, the Hong Kong court issued orders regarding litigation costs. Ultimately, it was ordered that Y1, Y2, Bank A, and B were to reimburse X1 and X2 for nearly the full amount of their expenses. Following an assessment of the specific sums, Y1, Y2, and B were liable for over 1.2 million Hong Kong dollars. No mention of interest on this amount was made in the order itself.

X1 and X2 then sought an execution judgment from Japanese courts to enforce this Hong Kong costs order, along with the associated cost assessment certificate and cost statement, against Y1 and Y2 in Japan. Both the court of first instance and the appellate court in Japan granted the execution judgment. Y1 and Y2 appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court addressed several key provisions, primarily under Article 24 of the Civil Execution Act and what was then Article 200 of the Code of Civil Procedure (subsequently revised and renumbered as Article 118, with largely similar content).

The Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions to grant the execution judgment. It meticulously addressed each of the appellants' arguments, clarifying several important legal principles:

I. Definition of a "Foreign Court Judgment"

The first issue was whether the Hong Kong costs order qualified as a "foreign court judgment" under Article 24 of the Civil Execution Act.

The Supreme Court held that a "foreign court judgment" refers to a final decision made by a foreign court concerning private law legal relations, under procedural guarantees for both parties, irrespective of the decision's name, procedure, or form. Therefore, even if termed a "decision" or "order," it falls under this definition if it possesses these characteristics.

In this case, the Hong Kong High Court, after the main judgments in favor of X1 and X2 became final, issued the costs order following a hearing involving Y1 and Y2's representatives. The specific amount was later determined by an assessment process. The Supreme Court found that this costs order, along with its related assessment documents, constituted a "foreign court judgment" for enforcement purposes in Japan.

II. Enforceability of Interest Not Explicitly Stated in the Foreign Judgment

The Hong Kong costs order did not explicitly mention interest on the awarded amount. Y1 and Y2 argued that such unstated interest should not be enforceable in Japan.

The Supreme Court, citing a previous 1997 decision, stated that the enforceability of interest accruing on a judgment sum is not precluded merely because it is not explicitly written in the foreign judgment itself. Whether interest is included in the judgment or accrues based on statutory provisions is often a technical difference in national legal systems.

The Court noted that under Hong Kong law, statutory interest automatically accrued on monetary judgments unless otherwise ordered, with the rate determined by the Chief Justice of the Hong Kong Supreme Court. As no specific order regarding interest was made in this case, the statutory interest applied. The Supreme Court upheld the lower court's decision to allow enforcement of this interest.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court stated that Japanese courts cannot investigate the appropriateness of the reasons for the foreign court imposing such interest or the validity of the interest rate itself, as this would amount to a re-examination of the merits of the foreign judgment, which is prohibited by Article 24, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Execution Act.

III. International Jurisdiction for Costs Orders (Indirect Jurisdiction)

For a foreign judgment to be recognized, the foreign court must have had international jurisdiction over the case (often referred to as "indirect jurisdiction"). The question was how to assess this for a costs order, which is ancillary to a main judgment.

The Supreme Court laid down the principle that the international jurisdiction for a costs order should generally be examined based on the international jurisdiction for the main underlying judgment(s).

The Court then elaborated on the general standard for determining indirect international jurisdiction: as there were no specific statutes or established international law principles directly governing this, it should be determined in accordance with "reason" (jōri), based on ideals of fairness between parties, and the appropriateness and promptness of the trial. Practically, this involves referring to Japan's domestic rules on territorial jurisdiction while considering the specific circumstances of each case from the perspective of whether it is appropriate for Japan to recognize the foreign judgment.

Since this 1998 decision, Japan's Code of Civil Procedure has been amended to include explicit provisions on direct international jurisdiction (Articles 3-2 et seq.). A later Supreme Court decision in 2014 suggested that while these direct jurisdiction rules should be a primary reference for determining indirect jurisdiction, the ultimate decision should still be made by considering all specific circumstances and "reason". The commentator criticizes this "reason" standard as vague and argues for a more direct application of the direct jurisdiction rules (the "mirror image theory") to enhance legal stability.

In the present case, the Supreme Court affirmed Hong Kong's jurisdiction over the underlying lawsuits based on various grounds, including the defendants' domicile (for the first lawsuit), the connection between claims (for the second lawsuit involving a subrogation claim related to the first), and the nature of a counterclaim (for the fourth lawsuit). For the third lawsuit, a third-party proceeding (a form specific to common law systems) by X1 and X2 for indemnification against Y1, Y2 and B, the Court found jurisdiction based on its close connection to the other concurrently litigated matters and the need for a unified resolution, referencing the spirit of Article 7 of the Code of Civil Procedure (consolidation of claims).

While the general principle of linking costs jurisdiction to main case jurisdiction is sound, there might be exceptions. For example, if a main case is dismissed due to lack of jurisdiction, and the defendant is awarded costs against the plaintiff, it might be inappropriate to automatically deny enforcement of that costs order in Japan if the foreign court had specific jurisdiction over the costs determination itself.

IV. Service of Process and Appearance (Code of Civil Procedure, Article 118, No. 2)

Article 118, No. 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure (then Article 200, No. 2) requires that the losing defendant either received service of the summons or order necessary for the commencement of the litigation in a manner compliant with the law, or appeared in the action without such service.

The Supreme Court provided a detailed interpretation:

- Service need not comply with Japanese procedural laws regarding service.

- However, the defendant must have actually been able to learn of the commencement of the proceedings and must not have been hindered in exercising their right to defend.

- Crucially, if a treaty on judicial assistance concerning service of documents exists between Japan and the judgment country, and that treaty prescribes the method of service for documents necessary for commencing proceedings, service not complying with the treaty method does not satisfy the requirements of Article 118, No. 2. This strict treaty compliance rule aims to uphold international agreements and protect defendants, as denial of recognition is often the only effective means for Japan to ensure the treaty is respected by the foreign state.

In this case, the "Notice of Motion" for the costs order was served on Y1 (an Indian national residing in Kobe, Japan) and Y2 (a Japanese company) by direct delivery in Japan through a Japanese lawyer privately retained by X1 and X2. At the time, both the UK (responsible for Hong Kong) and Japan were parties to the Hague Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters ("Hague Service Convention"). The Court found that this method of direct service by a private person was not permitted under the Hague Service Convention (as Japan had declared its objection to such methods under Article 10(b) and (c) of the Convention) nor was it based on any bilateral consular treaty. Therefore, the service was deemed improper under Article 118, No. 2.

However, the story didn't end there. Y1 and Y2, despite the defective service, appointed lawyers in Hong Kong and participated in the hearing for the costs order, including arguing against Hong Kong's jurisdiction in the third underlying lawsuit.

The Supreme Court then clarified the meaning of "appeared in the action" (応訴 - ōso) in Article 118, No. 2. It held that this "appearance" is different from an appearance that might create jurisdiction by consent. For the purpose of curing defective service under Article 118, No. 2, "appearance" means that the defendant was given an opportunity to defend and actually took defensive measures in court, even if those measures included contesting jurisdiction. Since Y1 and Y2 had appeared and defended in the Hong Kong costs proceedings, the defect in service was cured.

If the treaty compliance requirement is partly to protect interests beyond those of the individual defendant (e.g., state interests in orderly judicial assistance), it is questionable whether a defendant's appearance can "cure" a treaty violation. The fact that the Supreme Court examined the service requirements ex officio (on its own initiative) suggests the Court may view Article 118, No. 2 as protecting broader legal interests than just the individual defendant's.

V. Public Policy (Code of Civil Procedure, Article 118, No. 3)

Article 118, No. 3 states that recognition is denied if the judgment or its content is contrary to the public order or good morals of Japan. Y1 and Y2 argued that ordering them to pay the full litigation costs, including attorney's fees, on an "indemnity basis" was punitive and against Japanese public policy.

The Supreme Court held that the manner of allocating litigation costs is a matter for each country's legal system. As long as the costs awarded are within the scope of expenses actually incurred, ordering one party to bear the full amount, including attorney's fees, is not contrary to Japanese public policy.

In this specific case, the Hong Kong court had applied the "indemnity basis" for costs, considering Y1 and Y2's "insincere conduct" during the litigation. The Supreme Court acknowledged that this basis is exceptional in Hong Kong and contains a punitive element. However, because the awarded costs did not exceed the actual expenses incurred by X1 and X2, the content of the order was not deemed contrary to Japanese public policy. The Court distinguished this from punitive damages, the enforcement of which it had previously denied.

VI. Reciprocity (Code of Civil Procedure, Article 118, No. 4)

Finally, Article 118, No. 4 requires a "reciprocal guarantee": that the courts of the foreign country would recognize Japanese judgments under conditions not substantially different from those in Japan.

The Supreme Court, reaffirming a 1983 precedent, defined reciprocity as meaning that the country of the foreign court (in this case, Hong Kong) would recognize similar Japanese judgments under conditions that are not, in important respects, different from the requirements listed in Japan's Article 118.

While Japan was not specifically listed in Hong Kong's statutory list of countries with reciprocal enforcement arrangements, Hong Kong also recognized foreign judgments based on common law principles. The Supreme Court found that the requirements for recognizing foreign monetary judgments under Hong Kong common law (e.g., the foreign court had jurisdiction, the judgment was for a definite sum, final, and not obtained by fraud or contrary to public policy or natural justice) were not materially different from Japan's own requirements under Article 118. Therefore, the Court concluded that reciprocity existed between Japan and Hong Kong.

Significance of the Decision

This 1998 Supreme Court judgment is a seminal case in Japanese law on the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments. Its significance lies in:

- Comprehensive Clarification: It addressed and provided authoritative interpretations on multiple conditions listed in Article 118 of the Code of Civil Procedure (then Article 200) and Article 24 of the Civil Execution Act.

- Definition of "Foreign Judgment": It confirmed a broad definition, focusing on the substance (final decision on private rights with procedural guarantees) rather than the form or name of the foreign court's act.

- Interest: It affirmed the enforceability of interest not explicitly stated in the foreign judgment, treating variations in national practice as technical.

- Indirect Jurisdiction for Ancillary Orders: It established the principle of assessing jurisdiction for costs orders based on the main judgment's jurisdiction.

- Service of Process and Treaty Compliance: It provided a detailed interpretation of service requirements, emphasizing the importance of treaty compliance but also recognizing the curative effect of a defendant's appearance, even if to contest jurisdiction.

- Public Policy on Costs: It offered guidance on the public policy standard regarding the allocation of litigation costs, permitting full cost recovery if based on actual expenses, even if containing a punitive element for misconduct, distinguishing it from pure punitive damages.

- Reciprocity Standard: It reaffirmed the established test for reciprocity, looking at the overall similarity of recognition conditions, and found it satisfied with Hong Kong based on common law principles.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 28, 1998 decision remains a cornerstone for understanding how Japanese courts approach the complex task of recognizing and enforcing foreign judgments. By providing clear interpretations on several key legal requirements, the Court aimed to balance the need for international judicial cooperation with the protection of domestic legal principles and the rights of parties involved. This judgment continues to guide practitioners and courts in navigating the intricacies of cross-border litigation and enforcement in Japan.