Enforcing Connection: Japan's Supreme Court on Indirect Compulsion for Parent-Child Visitation Orders

Date of Judgment: March 28, 2013

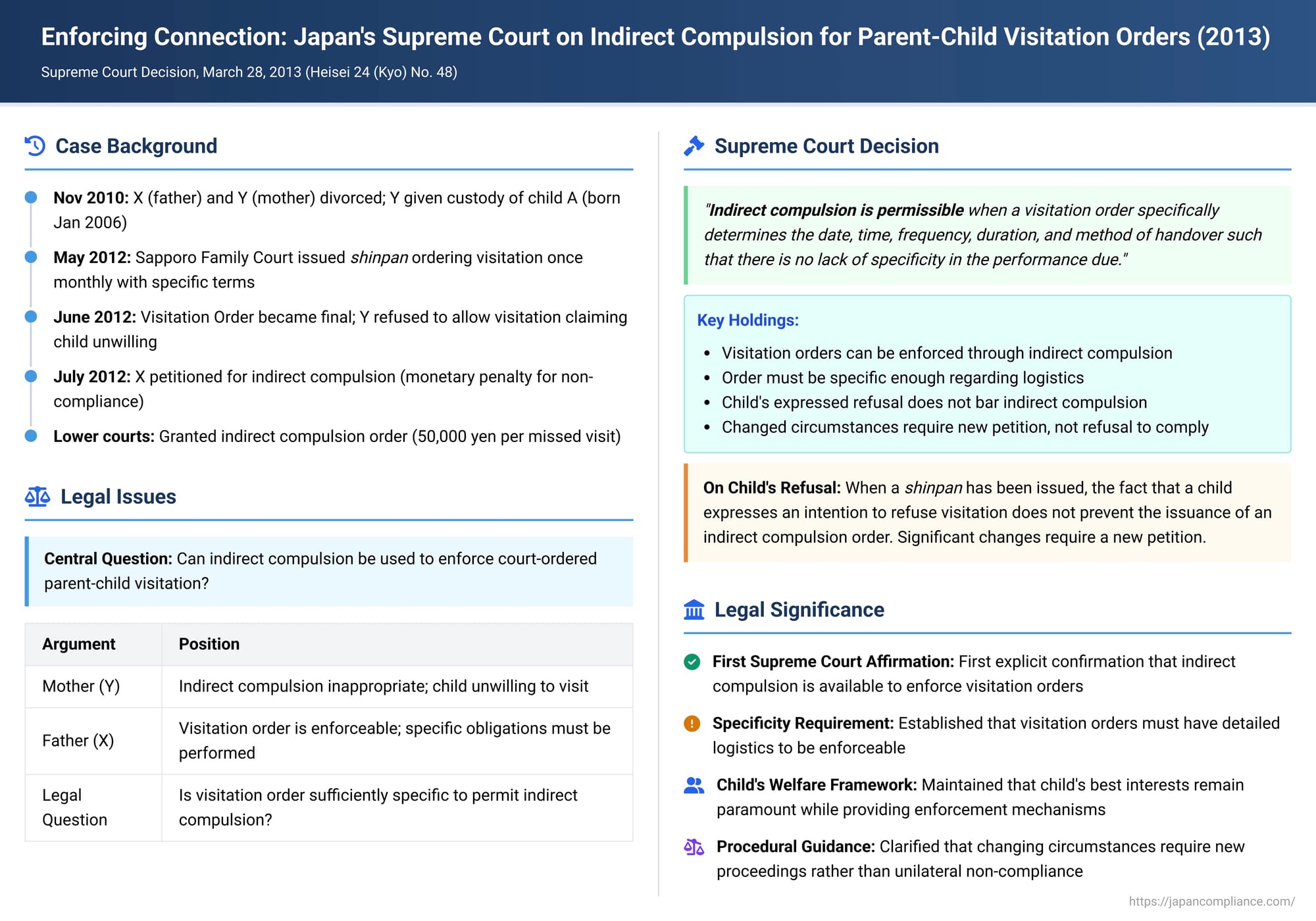

Parent-child visitation, known as menkai kōryū (面会交流) in Japan, is a crucial aspect of family law, intended to allow a child to maintain a relationship with their non-custodial parent after divorce or separation. While the importance of such contact for a child's well-being is widely recognized, ensuring its smooth implementation can be challenging, especially when there is animosity between parents. If a court issues an order (an umpire decision or shinpan) detailing specific visitation arrangements, but the custodial parent fails to comply, what enforcement mechanisms are available to the non-custodial parent? Specifically, can indirect compulsion—a legal tool where a court orders a party to pay a monetary penalty for each instance of non-compliance—be used to enforce visitation orders? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this critical issue in a decision on March 28, 2013 (Heisei 24 (Kyo) No. 48).

The Facts: A Court-Ordered Visitation Plan Met with Resistance

The case involved X (the father) and Y (the mother), who divorced by court judgment in November 2010. Y was designated as the sole custodian of their child, A, who was born in January 2006.

In May 2012, the Sapporo Family Court issued an umpire decision (shinpan) ordering Y to permit X to have visitation with A according to a detailed schedule. This shinpan became final and binding in June 2012 ("the Visitation Order"). The visitation schedule stipulated, among other things:

- Frequency and Duration: Visitation once a month, on the second Saturday from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM.

- Location: A place chosen by X, other than X's home, considering A's welfare.

- Child Handover Method: The handover location was to be a place other than Y's home, decided by mutual agreement, or if no agreement, near the east exit of "Station Ko." Y was to hand A over to X at the start of visitation, and X would return A to Y at the end. Y was not to be present during the visitation itself, except at the handover.

- Contingency for Missed Visits: If a scheduled visit could not occur due to A's illness or other unavoidable reasons, X and Y were to decide on an alternative date, considering A's welfare.

Despite this detailed court order, when X sought to exercise his visitation rights in June 2012, Y refused to allow it. Y claimed that A was consistently unwilling to see X and that forcing the visitation would negatively impact A.

Consequently, in July 2012, X petitioned the Sapporo Family Court for an order of indirect compulsion (間接強制 - kansetsu kyōsei) against Y, based on the Visitation Order. This would mean that Y would be ordered to pay X a certain amount of money for each instance she failed to comply with the visitation schedule. Y argued that indirect compulsion was not permissible, primarily because A was expressing a refusal to see X. The family court, however, granted X's petition, ordering Y to pay X 50,000 yen for each missed visitation. Y's appeal against this indirect compulsion order was dismissed by the High Court, leading Y to file a permission appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Indirect Compulsion for Visitation Orders Affirmed

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the indirect compulsion order. This was a landmark decision, as it was the first time the Supreme Court explicitly affirmed the availability of indirect compulsion as a means to enforce court-ordered parent-child visitation.

The Court's Reasoning:

- Child's Best Interests and Cooperative Implementation: The Court began by emphasizing that when determining parent-child visitation, "the child's interests should be given the highest priority (see Civil Code Art. 766(1))". Ideally, visitation should be carried out cooperatively between the custodial and non-custodial parents based on flexible terms.

- Enforceability of Visitation Orders: However, the Court noted that an umpire decision (shinpan) ordering visitation is an enforceable title of obligation, having the same effect as a final and binding judgment (under the then-applicable Family Affairs Adjudication Law). An order requiring a custodial parent to permit the non-custodial parent to have visitation with a child generally includes obligations such as handing over the child at a designated place and not interfering with the visitation. Such obligations, the Court found, "are not, by their nature, ones for which indirect compulsion is impossible".

- Specificity Requirement for Indirect Compulsion: The Court laid down a crucial requirement for an indirect compulsion order to be based on a visitation shinpan: "Therefore, in a shinpan ordering a custodial parent to permit a non-custodial parent to have visitation with a child, if the date and time or frequency of visitation, the duration of each visitation session, the method of child handover, etc., are specifically determined such that there is no lack of specificity in the performance due by the custodial parent, it is appropriate to construe that an indirect compulsion order can be issued against the custodial parent based on said shinpan."

- Child's Refusal Not an Absolute Bar to Indirect Compulsion: The Court addressed Y's argument concerning A's alleged refusal to see X: "And, a shinpan concerning child visitation can be said to have been made after considering the child's feelings, etc. Therefore, when a shinpan has been issued ordering a custodial parent to permit a non-custodial parent to have visitation with a child, the fact that the child expresses an intention to refuse visitation with the non-custodial parent—while it may be a reason to petition for mediation or a new shinpan to prohibit visitation or establish new terms for visitation if it can be said that circumstances different from those at the time of the said shinpan have arisen—does not constitute a reason to prevent the issuance of an indirect compulsion order based on the said shinpan."

Application to the Case:

The Supreme Court found that the Visitation Order in this case (the "Main Matter Stipulations") was sufficiently specific regarding the date, time, duration, and handover method for visitation, leaving no ambiguity in what Y was required to do. Therefore, an indirect compulsion order based on it was permissible. Y's assertions about A's refusal did not prevent the issuance of the indirect compulsion order.

The Significance of the Ruling: Enforcing the Child's Connection

This 2013 Supreme Court decision carries significant weight:

- Affirmation of Indirect Compulsion: It was the first time Japan's highest court explicitly confirmed that indirect compulsion (under Civil Execution Act Art. 172) is a permissible means of enforcing court-ordered parent-child visitation. This provided a much-needed clarification for a contentious area of family law practice. On the same day, the Supreme Court issued another decision affirming that indirect compulsion could also be used for visitation arrangements set out in a mediation agreement (調停調書 - chōtei chōsho).

- Emphasis on Specificity of Orders: The ruling underscored the critical importance of drafting visitation orders with a high degree of specificity regarding dates, times, durations, and handover logistics if they are to serve as a basis for indirect compulsion. This has clear implications for how family courts and practitioners frame such orders.

- Child's Refusal Handled Separately: The Court clarified that a child's subsequent refusal to participate in court-ordered visitation is not, in itself, a defense against an indirect compulsion order aimed at the custodial parent's compliance with their obligations (like facilitating handover). Instead, if the child's refusal represents a significant change in circumstances since the original order, the appropriate recourse is for the custodial parent to seek a modification or suspension of the visitation order through a new family court proceeding (mediation or shinpan).

While indirect compulsion—forcing compliance through financial penalties—is not always the ideal solution for fostering positive parent-child relationships, the Supreme Court acknowledged that in situations where a custodial parent is uncooperative, such measures may be necessary to uphold the child's interest in maintaining contact with the non-custodial parent, an interest that the original visitation order presumably found to be in the child's welfare.

Legal Framework and Debates Surrounding Visitation Enforcement

The enforcement of visitation orders has been a challenging area in Japanese family law.

- Legal Basis for Visitation: Before the 2011 revision of the Civil Code, there was no explicit statutory provision for "visitation and contact." Courts typically grounded orders in Civil Code Article 766 (concerning matters to be decided upon divorce, including child custody) often by analogical application if parents were merely separated. The 2011 revision explicitly added "visitation and contact with the child" and "sharing of expenses necessary for child's custody" to Article 766, solidifying its legal basis in divorce contexts.

- Enforceability of Shinpan and Mediation Agreements: Final family court shinpan orders and formal mediation agreements have the force of an enforceable title of obligation.

- Types of Enforcement: Because visitation involves ongoing, personal obligations and cannot be physically performed by a third party, direct physical enforcement (直接強制 - chokusetsu kyōsei) or alternative execution (代替執行 - daitai shikkō) are generally considered unsuitable. This leaves indirect compulsion as the primary, albeit imperfect, coercive tool.

- Arguments Against Indirect Compulsion: Some legal practitioners and scholars had previously expressed reservations about using indirect compulsion for visitation, citing concerns that forcing contact against a custodial parent's strong opposition, or when a child expresses refusal, might be detrimental to the child's welfare.

- Arguments For Indirect Compulsion: The prevailing view, however, leaned towards allowing it, recognizing that without some enforcement mechanism, court orders for visitation could become meaningless, potentially harming the child's long-term interest in having a relationship with both parents. The Supreme Court's 2013 decisions strongly endorsed this latter view.

The Specificity Requirement in Practice

The Supreme Court's emphasis on the need for the visitation order to be highly specific regarding the "date and time or frequency of visitation, the duration of each visitation session, the method of child handover, etc." has become a crucial guideline.

- Lower court cases prior to this ruling had already established that vague terms (e.g., visitation "as agreed by parties" or allowing the non-custodial parent to "choose" unspecified details) were often deemed insufficiently specific for enforcement.

- This Supreme Court ruling solidified this requirement. Legal commentary suggests that while the standard for specificity is strict, some lower courts after this ruling have shown a degree of flexibility, considering implied understandings between parties if the core elements are clear, even if not every minute detail is explicitly spelled out in the order.

Handling a Child's Refusal to Attend Visitation

One of the most difficult aspects of enforcing visitation is when a child, particularly an older child, expresses a clear refusal to see the non-custodial parent.

- The Supreme Court's position is that the original visitation order would have been made after due consideration of the child's welfare and, implicitly, their general circumstances and feelings at that time. Therefore, a subsequent expression of refusal by the child does not automatically negate the custodial parent's obligation to comply with the existing order nor does it block an indirect compulsion order against that parent.

- The proper course, as indicated by the Supreme Court, is for the custodial parent to file a new petition in family court to modify or suspend the visitation order if the child's refusal constitutes a significant change in circumstances that genuinely makes visitation contrary to their welfare.

- This approach is intended to prevent the custodial parent from unilaterally thwarting a court order by citing the child's reluctance, while still providing a mechanism to address legitimate changes in the child's needs or wishes through a further judicial process.

- However, legal commentary notes ongoing debate about how such "new circumstances" (like a child's persistent refusal) should be handled procedurally—whether through a new shinpan as suggested, a formal "action to oppose execution" (seikyū igi no uttae), or if it can be considered within the indirect compulsion proceedings themselves. Recent lower court practice sometimes considers the child's refusal within the indirect compulsion hearing, occasionally leading to dismissal of the enforcement request if visitation is deemed truly contrary to the child's current welfare.

Conclusion: Strengthening the Enforceability of Parent-Child Contact

The Supreme Court's March 2013 decisions on indirect compulsion for parent-child visitation orders represent a significant step in strengthening the legal mechanisms for ensuring that children can maintain relationships with both parents after separation or divorce, provided such contact is in their best interests. By affirming the availability of indirect compulsion and clarifying the need for specific and detailed visitation orders, the Court provided clear guidance to lower courts and legal practitioners. While emphasizing that the child's welfare remains paramount and that cooperative solutions are always preferable, the ruling acknowledges that, in some instances, coercive measures may be necessary to uphold court-determined arrangements designed to benefit the child. The decisions continue to shape practice and ongoing discussions about how best to balance the rights and interests of all parties while prioritizing the well-being of children in post-separation families.