Enforcing Child Visitation in Japan: The Supreme Court's Stance on Indirect Compulsion

Date of Supreme Court Decision: March 28, 2013

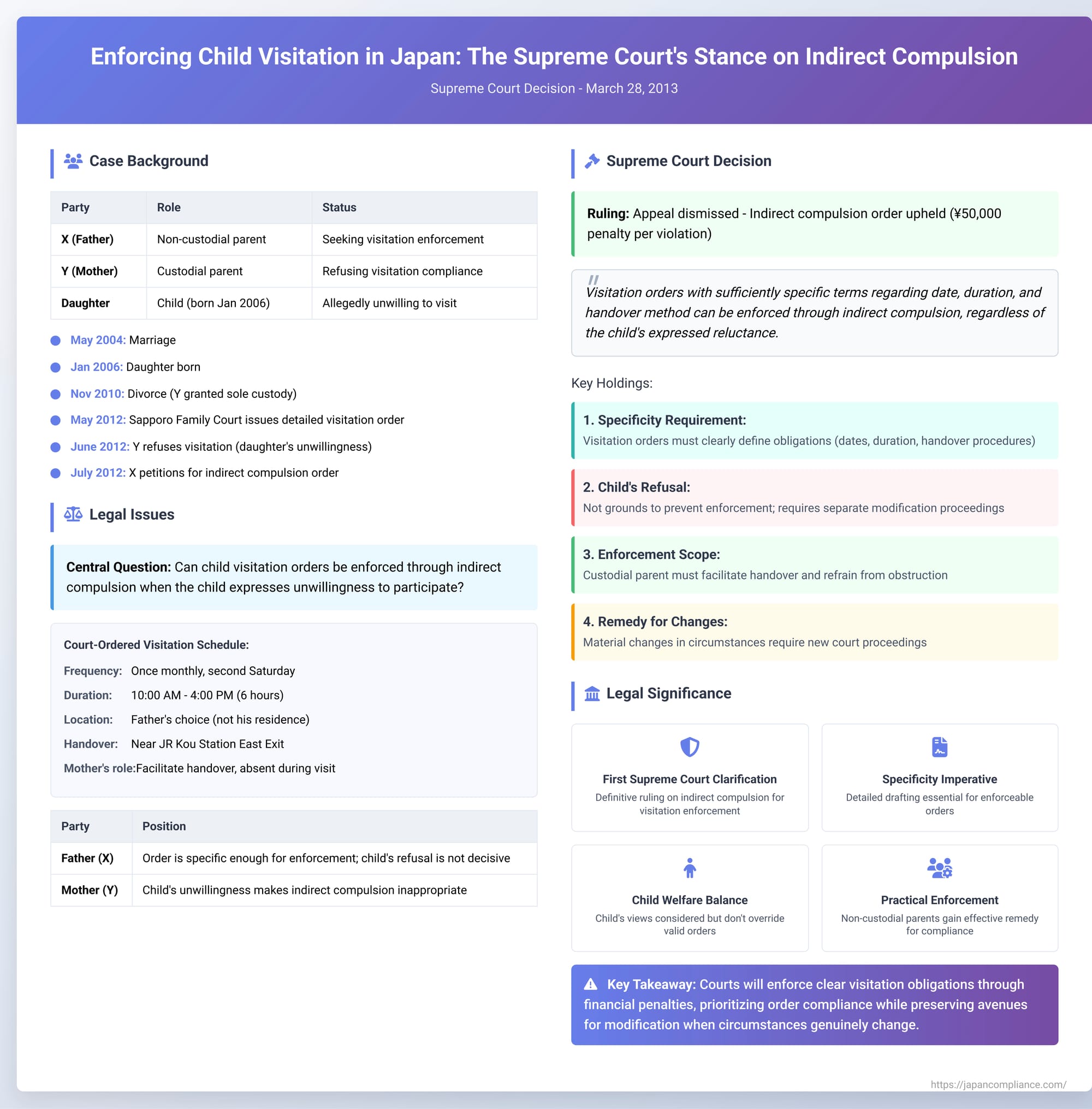

The delicate and often emotionally charged issue of child visitation rights following a divorce presents significant legal challenges worldwide. In Japan, a landmark decision by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court on March 28, 2013, provided crucial clarifications on the use of "indirect compulsion" (間接強制 - kansetsu kyosei) to enforce visitation orders. This case sheds light on the balance between ensuring a non-custodial parent's access to their child, the custodial parent's obligations, and the overarching principle of the child's welfare.

Background of the Dispute

The case involved X, the father, and Y, the mother, who divorced in November 2010 after marrying in May 2004 and having a daughter in January 2006. The divorce decree granted Y sole custody of their daughter.

Subsequently, in May 2012, the Sapporo Family Court issued a judicial decision (hereinafter referred to as the "Visitation Order") outlining the terms of X's visitation with his daughter. This order was finalized in June 2012. The specifics of this "Visitation Schedule" (本件要領 - Honken Youryou) were detailed as follows:

- Frequency and Duration: Visitation was to occur once a month, on the second Saturday, from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM.

- Location: The venue for visitation would be determined by X (the father), considering the child's welfare, but it could not be X's residence.

- Handover Protocol:

- The handover location was to be a place other than Y's (the mother's) residence. The parties were to decide this through mutual consultation.

- If they could not agree, the handover was to take place near the East Exit ticket gate of JR Kou Station.

- Y was to bring the daughter to the handover location at the start of the visitation period, and X would return the daughter to Y at the same location at the end.

- Crucially, Y was not to be present during the visitation itself, aside from the handover.

- Contingency for Missed Visitations: If a scheduled visitation could not occur due to the child's illness or other unavoidable reasons, X and Y were to consult and decide on an alternative date, always prioritizing the child's welfare.

- Participation in School Events: Y was not to prevent X from attending the daughter's significant school events, such as entrance ceremonies, graduation ceremonies, and sports days (excluding regular parent observation days).

Despite this detailed court order, when X sought to exercise his visitation rights in June 2012, Y refused. She stated that their daughter was unwilling to participate in the visitation and that forcing the issue would negatively affect the child.

In response to this refusal, X petitioned the Sapporo Family Court in July 2012 for an indirect compulsion order. This legal mechanism would require Y to comply with the Visitation Order or face a monetary penalty for each instance of non-compliance. Y contested this, arguing primarily that the daughter's expressed refusal to see X made an indirect compulsion order inappropriate.

The Sapporo High Court, acting as the lower appellate court, sided with X. It found that the Visitation Schedule was sufficiently specific in its terms to define Y's obligations. Furthermore, the High Court ruled that the daughter's alleged refusal did not constitute a circumstance that would negate the appropriateness of an indirect compulsion order. The High Court ordered Y to permit visitation as per the Visitation Schedule and stipulated a penalty of 50,000 yen payable to X for each failure to comply. Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment and Reasoning

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated March 28, 2013, dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's indirect compulsion order. The Court's reasoning meticulously addressed the nature of visitation rights, the requirements for indirect compulsion, and the role of a child's expressed wishes in enforcement proceedings.

1. The Nature and Purpose of Visitation Orders:

The Court began by emphasizing that when determining visitation arrangements between a custodial parent and a non-custodial parent, the child's best interests must be the paramount consideration (a principle rooted in Article 766, Paragraph 1 of the Japanese Civil Code). Ideally, visitation should occur under flexible terms agreed upon and facilitated by the cooperation of both parents.

However, the Court also clarified that a judicial decision ordering a custodial parent to permit visitation (a "performance order") carries the same force as an enforceable judgment (as per the former Family Affairs Adjudication Act, Article 15, now equivalent to Article 75 of the Family Case Procedure Act). Such an order, at a minimum, obligates the custodial parent to hand over the child to the non-custodial parent at the specified location and to refrain from obstructing the visitation. The Court found that obligations of this nature are not inherently unsuitable for enforcement via indirect compulsion.

2. Specificity Requirement for Indirect Compulsion:

A critical point in the Supreme Court's reasoning was the requirement for specificity. The Court stated that an indirect compulsion order can be issued based on a visitation order if the terms—such as the date or frequency of visitation, the duration of each visit, and the method of child handover—are so concretely defined that there is no ambiguity regarding the custodial parent's obligations.

Applying this to the present case, the Supreme Court found that the "Honken Youryou" (Visitation Schedule) was indeed sufficiently specific. It clearly laid out:

- Date and Frequency: Once a month, on the second Saturday.

- Duration: 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM (6 hours).

- Method of Handover: Detailed provisions including default locations if parents couldn't agree, and the requirement for the custodial parent to bring the child and the non-custodial parent to return the child.

Because these elements were clearly defined, the Court concluded that Y's obligations were specified to a degree that permitted the issuance of an indirect compulsion order.

3. The Child's Expressed Refusal:

The Court directly addressed Y's main argument: that her daughter's unwillingness to see X should prevent the issuance of an indirect compulsion order. The Supreme Court's stance on this was nuanced.

It acknowledged that judicial decisions regarding child visitation are typically made after considering the child's feelings and circumstances. Therefore, an existing visitation order already presumes a certain understanding of the child's perspective at the time it was made.

The Court ruled that a child's subsequent expression of refusal to participate in court-ordered visitation is not, in itself, a valid reason to block an indirect compulsion order aimed at enforcing that existing visitation order.

However, the Court did provide an avenue for addressing such situations. It suggested that if the child's refusal signifies that circumstances have materially changed since the original Visitation Order was issued, this could constitute grounds for the custodial parent (or other relevant parties) to:

- Petition the court to prohibit the visitation outlined in the original order.

- Seek a new court ruling or mediation to establish revised terms for visitation.

In essence, the child's refusal is a matter to be dealt with by potentially modifying the underlying visitation order itself through a separate family court proceeding, rather than as a defense against the enforcement of a currently valid order via indirect compulsion.

4. Upholding the Lower Court's Decision:

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court found no error in the High Court's judgment. The existing Visitation Schedule was specific enough to support an indirect compulsion order, and Y's arguments concerning her daughter's refusal were not deemed sufficient to prevent such an order. The appeal was dismissed, and the costs were to be borne by Y, the appellant.

Implications and Significance of the Ruling

This Supreme Court decision carries significant weight in the landscape of Japanese family law, particularly concerning the enforcement of non-monetary obligations related to child welfare.

Affirmation of Indirect Compulsion for Visitation:

This was a landmark clarification from Japan's highest court, explicitly stating that indirect compulsion is a viable tool for enforcing visitation orders. Previously, while lower courts had increasingly leaned towards allowing it for efficacy, there was some debate. The Supreme Court settled this, recognizing that without effective enforcement mechanisms, visitation orders could become mere suggestions rather than binding obligations. The Court understood that direct physical enforcement (e.g., authorities forcibly taking a child for visitation) is generally considered too detrimental to the child's well-being in the context of ongoing visitation, and alternative performance (having a third party fulfill the obligation) is not practical. Thus, indirect compulsion, which applies psychological pressure through financial penalties, was affirmed as an appropriate method.

Emphasis on Specificity in Drafting Orders:

The ruling underscores the critical importance of drafting highly specific and unambiguous visitation agreements or court orders if indirect compulsion is ever to be a potential enforcement route. The Court's approval of the "Honken Youryou" was directly tied to its detailed provisions regarding:

- Timing: Exact dates/days or a clear formula (e.g., "every second Saturday").

- Duration: Clear start and end times for each visit.

- Handover Logistics: Precise details about who is responsible for pick-up and drop-off, where this will occur (with fallback provisions if agreement fails), and the custodial parent's duty to present the child.

On the same day, the Supreme Court reportedly issued other decisions that denied indirect compulsion in cases where visitation terms lacked such specificity. For instance, terms like "visitation approximately once every two months," or "duration to start at one hour and gradually increase," or where the method of handover was left entirely to future agreement without default provisions, were deemed insufficiently concrete to support indirect compulsion. This contrast highlights that general undertakings to "allow visitation" or "cooperate on scheduling" are unlikely to pass the specificity test for this type of enforcement.

Navigating a Child's Reluctance:

The Court's position on a child's refusal is particularly noteworthy. It differentiates between the factors considered when initially establishing visitation terms (where the child's feelings, age, and maturity are central) and the considerations during enforcement of an existing order. While the child's welfare remains paramount, a subsequent refusal by the child does not automatically invalidate or render unenforceable a previously issued order.

The ruling directs parties to the proper forum for addressing such changes: a new application to the family court to modify or suspend the existing visitation order. This ensures that any re-evaluation of the child's best interests, in light of new circumstances like persistent refusal, occurs within a judicial process equipped to investigate and consider all relevant factors, including potentially appointing family court investigators to understand the child's true wishes and the reasons behind them. It prevents the enforcement process from becoming a re-litigation of the visitation terms themselves.

The Tension Between Ideal Cooperation and Necessary Enforcement:

The Supreme Court acknowledged the ideal scenario: visitation carried out flexibly, based on the mutual understanding and cooperation of both parents. Japanese family law often encourages parents to resolve matters through discussion and agreement, prioritizing the child's emotional stability. However, this decision recognizes the reality that cooperation sometimes breaks down. In such instances, the legal framework must provide a path for enforcement, provided the obligations are clearly defined. The judgment implicitly encourages parents and their legal representatives, even during the initial stages of divorce or separation, to consider the enforceability of visitation terms and to strive for clarity and precision, especially if the parental relationship is acrimonious.

What This Means for Parents:

For non-custodial parents, this ruling offers a pathway to enforce their visitation rights, provided the underlying order is meticulously drafted. It signals that courts will support the enforcement of clear obligations.

For custodial parents, the decision underscores their duty to comply with specific court-ordered visitation terms. A child's reluctance, while a serious concern that may warrant a review of the visitation arrangement itself, cannot be unilaterally used to defy a clear court order without facing potential sanctions like indirect compulsion. The onus is on the custodial parent to actively facilitate the visitation as ordered, which includes the physical act of handing over the child.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 28, 2013, decision provides a foundational framework for understanding the enforcement of child visitation orders in Japan through indirect compulsion. It champions the principle that court orders must be respected and are enforceable, while simultaneously reiterating that the child's welfare is the guiding star in all family law matters. The key practical lesson is the absolute necessity for precision and concreteness in the articulation of visitation schedules if they are to be effectively enforced through indirect financial penalties. While the law seeks to foster cooperation, it also provides remedies when cooperation falters, ensuring that the rights and obligations surrounding one of the most important post-divorce relationships—that between a child and a non-custodial parent—are not left to chance.