Enforcing a Right of Retention Over Registered Automobiles in Japan: Supreme Court Clarifies Evidentiary Requirements for Auction

In Japanese civil law, a "right of retention" (留置権 - ryūchiken) is a possessory security right that allows a person who holds an object belonging to another to retain possession of that object until a claim connected with the object is satisfied (Civil Code, Article 295). For instance, a garage might retain a repaired car until the repair bill is paid. While primarily a defensive right to hold onto property, a holder of a right of retention can also, under certain circumstances, initiate a compulsory auction of the retained property to indirectly encourage payment or to relieve themselves of the burden of continued retention. This auction process, though not aimed directly at debt satisfaction like typical security interest enforcement, largely follows the rules for auctions based on formal security interests (Civil Execution Act, Article 195).

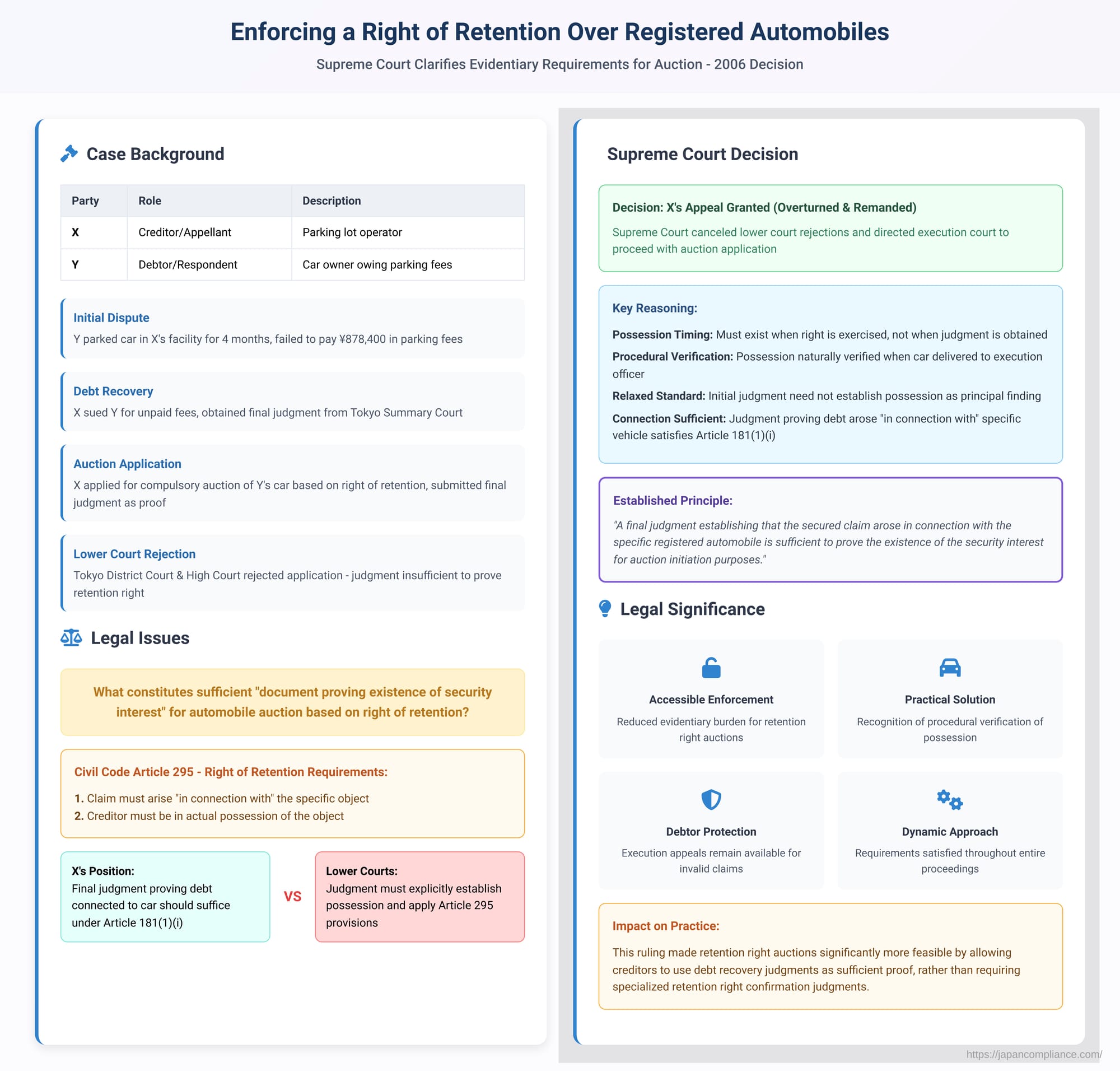

When the retained property is a registered automobile, specific procedural requirements for commencing such an auction come into play. A key requirement under Article 181, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Execution Act is the submission of a "document proving the existence of the security interest" (担保権証明文書 - tanpoken shōmei bunsho). For a right of retention, which cannot itself be registered, this often means providing a "final and binding judgment proving the existence of the security interest" (Article 181(1)(i)). A 2006 Supreme Court of Japan decision provided critical clarification on what type of judgment satisfies this requirement, particularly concerning the element of the creditor's possession of the vehicle.

Background of the Dispute

The creditor, X (appellant), operated a business with a parking lot. X claimed that the debtor, Y (respondent), had parked Y's car (a registered automobile) in X's paid parking facility, thereby entering into a parking usage agreement. Y allegedly failed to pay parking fees for a period of four months, accumulating a debt of 878,400 yen.

X sued Y for these unpaid parking fees and associated late charges. X was successful, obtaining a final and binding judgment from the Tokyo Summary Court that ordered Y to pay the claimed amount (the "Said Final Judgment"). This judgment explicitly recognized Y's debt to X for the parking fees related to Y's car.

Subsequently, X sought to enforce a civil law right of retention over Y's car, which X presumably still possessed, to secure the unpaid parking fees. X applied to the execution court to initiate a compulsory auction of Y's car. In support of this application, X submitted the Said Final Judgment, contending that it constituted a "final and binding judgment proving the existence of a security interest" as required by Article 181(1)(i) of the Civil Execution Act (this article is applied to auctions of registered automobiles based on security interests through Article 195 of the Act and Article 176, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Execution Rules).

The Tokyo District Court (acting as the execution court) rejected X's auction application. It found that the Said Final Judgment, while proving the debt, did not sufficiently prove the existence of the right of retention itself. X appealed this decision to the Tokyo High Court.

The Tokyo High Court upheld the execution court's rejection. It reasoned that for the Said Final Judgment to qualify, the right of retention needed to have been either the direct subject matter of the lawsuit or a core element (like a cause of action or a defense) related to the subject matter. The High Court found that the Said Final Judgment did not specifically identify and find the facts constituting the cause for the right of retention (particularly X's possession of the car) and then explicitly apply the provisions of Civil Code Article 295 (which governs rights of retention) to those facts. Therefore, the High Court concluded, the judgment did not "prove" the existence of the right of retention in the manner required by the Civil Execution Act.

X then sought and was granted permission to appeal to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision, canceled the original execution court's decision to reject the auction application, and remanded the case to the Tokyo District Court (the execution court) for further proceedings (effectively directing it to proceed with X's auction application).

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Elements of a Civil Law Right of Retention: The Court first outlined the two essential requirements for the formation of a civil law right of retention under Article 295 of the Civil Code:

- (i) The creditor must possess a claim that has arisen "in connection with" the specific object being retained (this establishes the necessary link or kenrensei between the claim and the object).

- (ii) The creditor must be in actual possession of that object.

- The Nature of the Possession Requirement: Regarding the second requirement (possession of the object), the Supreme Court explained that if a creditor holds a claim that is connected to the object (satisfying the first requirement), a right of retention arises by operation of law whenever the creditor subsequently acquires possession of that object. This can happen at any time after the connected claim arises and through various lawful means. Crucially, the Court stated that this possession requirement must exist at the time the right of retention is exercised, and its existence at that specific time is sufficient.

- Possession in the Context of Auctioning Registered Automobiles: When a registered automobile is to be auctioned based on a right of retention, the Civil Execution Act and its implementing rules envision a specific procedure. After the execution court issues an auction commencement decision, the execution officer is scheduled to promptly take delivery of the automobile from the retaining creditor. If the creditor fails to deliver the automobile to the execution officer, the auction proceedings will be canceled.

Therefore, the Supreme Court reasoned, the fact of the creditor's possession of the registered automobile will naturally and inevitably become clear during the subsequent course of the auction proceedings themselves. - Relaxed Standard of Proof for Possession in the Initial Judgment: Given that possession is a requirement that must exist at the time the right of retention is effectively exercised (which, in the context of an auction of a registered automobile, is when the car must be handed over to the execution officer after the auction commences), the "final and binding judgment proving the existence of the security interest" (as required by Article 181(1)(i) to initiate the auction) does not need to have the fact of the creditor's possession of the registered automobile established as a principal finding within that judgment itself. The subsequent procedural steps will verify possession.

- Sufficient Content for the Initiating Judgment: Consequently, for initiating a compulsory auction of a registered automobile based on a civil law right of retention, a final and binding judgment which establishes as a principal fact that the underlying secured claim (the debt) arose in connection with that specific registered automobile is sufficient to qualify as a "final and binding judgment proving the existence of the security interest" under Article 181(1)(i) of the Civil Execution Act.

- Application to X's Case: Applying this standard, the Supreme Court found that while X's Said Final Judgment did not explicitly establish as a principal fact that X was in possession of Y's car, it did definitively establish that X's claim for unpaid parking fees arose "in connection with" Y's specific car. Therefore, the Said Final Judgment did meet the requirements of Article 181(1)(i), and its submission by X was sufficient to allow the commencement of the auction proceedings.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 2006 Supreme Court decision significantly clarified and, in practical terms, eased the evidentiary burden for creditors seeking to enforce a civil law right of retention by auctioning registered automobiles (and by extension, other similarly registered movable properties like construction machinery or small vessels where the execution officer takes possession).

- Facilitating Auctions Based on Rights of Retention: The ruling recognized the practical difficulties creditors often face in obtaining a prior judgment that explicitly adjudicates all elements of a right of retention, especially the ongoing fact of possession, before they can even apply for an auction. By relaxing the requirement for the initial judgment to prove possession, the Court made such auctions more accessible.

- Background on Right of Retention Auctions and Required Documents:

The PDF commentary provides useful context. An auction based on a right of retention is authorized by Article 195 of the Civil Execution Act, which directs that such auctions follow the rules applicable to auctions for the enforcement of formal security interests. For registered automobiles, which are treated similarly to real property for certain enforcement purposes due to their registration system (Civil Execution Rules, Article 176(2)), the auction is commenced not by the physical seizure or delivery of the car to a bailiff (as with ordinary, unregistered movables), but by the creditor submitting specific "documents proving the security interest" to the execution court as per Article 181(1) of the Civil Execution Act.

Since a right of retention itself is a possessory lien that cannot be registered in any public registry, Article 181(1)(iii) (which allows for a certificate of registered matters as proof of certain security interests) is inapplicable. This leaves creditors with two main options for proving a right of retention:- Article 181(1)(i): A final and binding judgment (or certain other judicial orders) proving the existence of the security interest.

- Article 181(1)(ii): A transcript of a notarial deed.

However, a notarial deed specifically creating a right of retention is highly unusual, and one confirming its existence or referencing it within a debt acknowledgment would typically require the debtor's cooperation, making it an uncommon document in contentious situations. Thus, a "judgment proving the security interest" under item (i) is often the most practical, if not only, route.

Prior to this Supreme Court decision, it was generally thought that such a judgment would need to have the right of retention itself as the direct subject matter (e.g., an action to confirm the right of retention) or as a key finding in its reasoning (e.g., a judgment in a replevin action where the creditor successfully raised the right of retention as a defense, resulting in a judgment for delivery conditional upon payment). Such specific judgments are not always readily available.

- The Supreme Court's Pragmatic Solution: The Court's decision to separate the two core elements of a right of retention—(1) the claim connected to the object and (2) the creditor's possession of the object—was key. It reasoned that for registered automobiles, the second element (possession) will be effectively verified during the auction process itself: if the creditor cannot deliver the car to the execution officer after the auction commencement decision, the proceedings are simply canceled. Therefore, the judgment submitted at the outset to merely initiate the auction primarily needs to establish the first element: the connection between the debt and the specific vehicle.

- Procedural Safeguards for the Debtor: The PDF commentary notes that this approach means the debtor might not have a pre-auction judicial review specifically focused on the creditor's possession or the overall validity of the right of retention if the initial judgment (like X's parking fee judgment) only covered the underlying debt. However, the system provides safeguards:

- The auction process itself inherently verifies possession when delivery to the execution officer is required.

- If the debtor has grounds to dispute the existence or validity of the right of retention (e.g., arguing facts that would negate or extinguish the right, which may not have been relevant or litigable in the prior debt recovery lawsuit), they can raise these issues during the auction proceedings, typically through an "execution appeal" (執行抗告 - shikkō kōkoku) against the auction commencement decision, as provided by Article 182 of the Civil Execution Act (which applies to security interest auctions). The Supreme Court appears to believe that this mechanism offers sufficient protection against unfounded sales based on an invalid assertion of a right of retention.

This reflects a "procedural and dynamic" perspective, where the requirements for the right of retention are considered satisfied if all necessary elements become evident and are confirmed throughout the entire course of the execution proceedings, rather than demanding that every single element be definitively proven by the initial judgment submitted to merely start the process.

- Reception and Ongoing Discussion: The decision has generally been viewed positively by legal scholars for its practical effect of making auctions based on rights of retention more feasible. However, there has been some academic critique of the Court's specific phrasing that possession need only exist "at the time the right is exercised," with debate over whether this "exercise" refers to the auction application, the later delivery to the execution officer, or the very formation of the right itself.

The PDF commentary also mentions that while this ruling clarifies the path for civil rights of retention, extending its exact logic to commercial rights of retention might be more complex, as the elements of a commercial lien (e.g., possession obtained through a commercial transaction, debtor's ownership at the time of possession acquisition by the creditor for the debtor's benefit) are less likely to be established as principal facts in a simple judgment for an underlying commercial debt.

Finally, despite this helpful clarification by the Supreme Court, the practical difficulty for creditors in obtaining any form of "judgment proving the security interest" or a suitable notarial deed remains a challenge. The academic debate about whether private documents should be allowed to prove a right of retention (by analogy to Article 181(1)(iv) for certain statutory liens), a theory not addressed by this Supreme Court decision, therefore continues.

Conclusion

The 2006 Supreme Court of Japan decision significantly streamlined the process for creditors seeking to enforce a civil law right of retention by auctioning registered automobiles. By ruling that a final judgment establishing the underlying debt and its direct connection to the specific vehicle is sufficient to initiate the auction proceedings—with the creditor's actual possession of the vehicle to be confirmed during the subsequent procedural steps—the Court adopted a pragmatic approach. This reduces the initial evidentiary burden on the retaining creditor, while still incorporating safeguards within the auction process to verify possession and allow debtors to raise substantive objections to the asserted right of retention. The decision reflects a dynamic view of procedural requirements, ensuring that the legal framework facilitates the practical exercise of possessory security rights.