Enforcement Proceedings vs. Bankruptcy: When Does Enforcement "Terminate" in Japan?

Date of Decision: April 18, 2018 (Heisei 30)

Case Name: Appeal Against Dismissal of Execution Appeal Regarding Cancellation of Share Seizure Order (Permitted Appeal)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

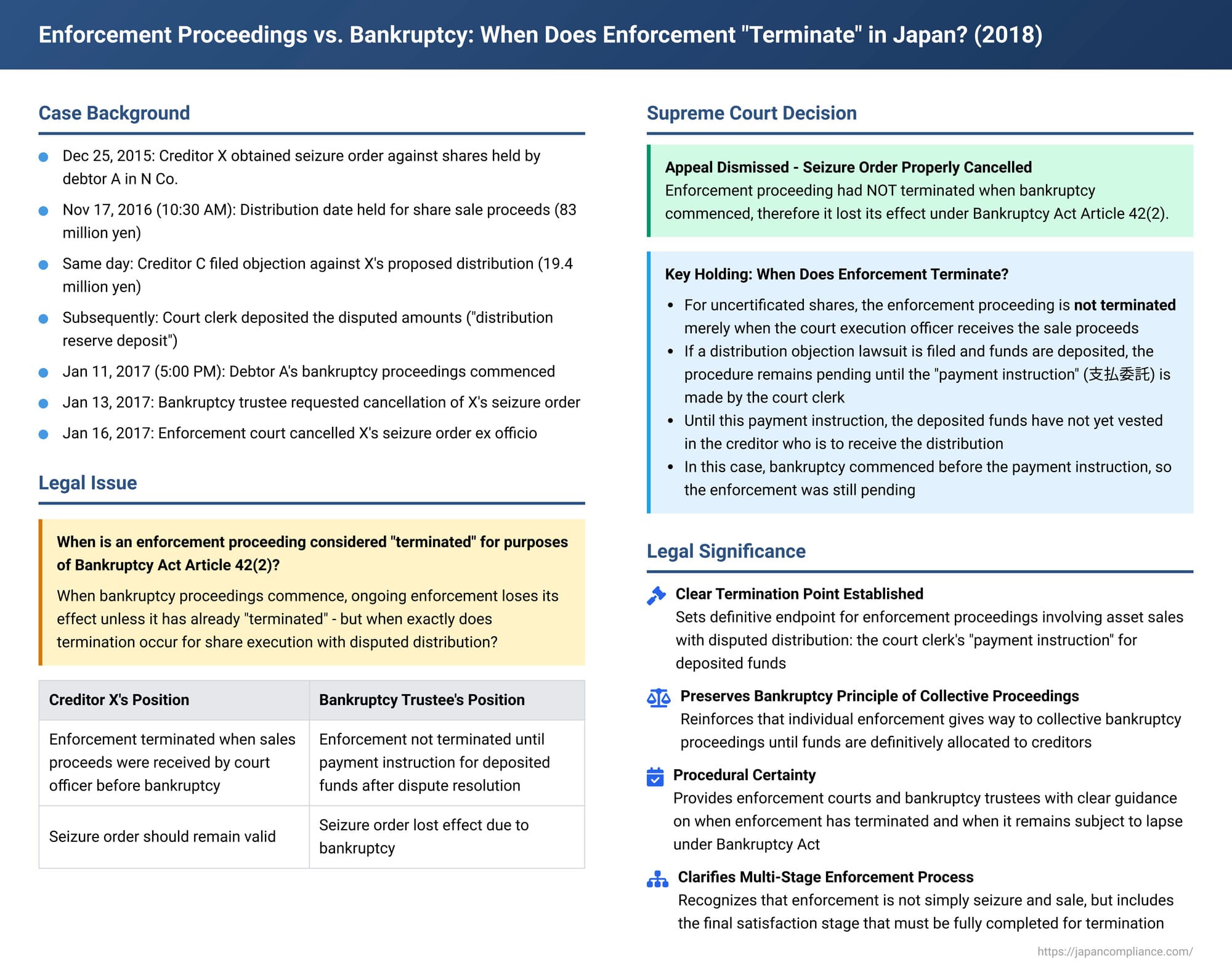

This blog post explores a 2018 Supreme Court of Japan decision that clarifies a critical juncture in civil enforcement proceedings: the exact point at which such proceedings are considered "terminated," particularly when the debtor subsequently enters bankruptcy. The timing is crucial because under Japan's Bankruptcy Act, ongoing enforcement actions against a bankrupt debtor's assets generally lose their effect.

Facts of the Case

The creditor, X (the appellant), obtained a seizure order on December 25, 2015, against uncertificated shares (excluding "book-entry transfer shares" under the Act on Book-Entry Transfer of Company Bonds, Shares, etc., Article 128(1)) held by debtor A in N Co., Ltd. (the "Seized Shares"). Three other creditors also obtained seizure orders against these shares.

A sale order was issued for the Seized Shares, and they were sold. On November 17, 2016, at 10:30 AM, a distribution date was held for the sales proceeds, which amounted to 83,149,836 yen. On that day, another creditor, C, filed an objection against the entire proposed distribution amounts for X (19,405,299 yen) and another creditor, B (35,305,783 yen). C subsequently filed a "distribution objection lawsuit" (配当異議の訴え - haitō igi no uttae) against X and B within the prescribed period. For the portions of the distribution to which no objection was made, the enforcement court carried out the distribution. However, for the disputed portions (those affecting X and B), the court clerk of the enforcement court deposited the funds, a procedure known as a "distribution reserve deposit" (配当留保供託 - haitō ryūho kyōtaku).

Debtor A received a bankruptcy commencement decision at 5:00 PM on January 11, 2017, and a bankruptcy trustee was appointed. On January 13, the trustee submitted a written request to the enforcement court seeking the cancellation of X's seizure order. On January 16, the enforcement court, acting ex officio (on its own initiative), issued a decision cancelling X's seizure order. X filed an execution appeal against this cancellation, but the appellate court dismissed it. X then filed a permitted appeal to the Supreme Court, arguing that the enforcement proceeding had already terminated when the sales proceeds were received by the court officer, and therefore Bankruptcy Act Article 42, Paragraph 2 (main text) should not apply .

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions .

The Court's core reasoning was as follows:

- Bankruptcy Act Article 42, Paragraph 2 (Main Text): This provision states that when a bankruptcy commencement decision is made, any pending enforcement proceedings based on bankruptcy claims against property belonging to the bankruptcy estate lose their effect against the estate. However, this provision does not apply if, at the time of the bankruptcy commencement decision, the enforcement proceeding has already "terminated".

- Enforcement Procedures for Uncertificated Shares:

- For uncertificated shares (not book-entry transfer shares), the Civil Execution Act requires that if the shares are sold pursuant to a sale order, the enforcement court must then implement distribution, etc. (配当等 - haitō tō, which includes distribution or delivery of allocated payment) from the proceeds (Civil Execution Act Article 167, Paragraph 1, and Article 166, Paragraph 1, Item 2).

- Effect of Distribution Objection and Deposit:

- If a distribution objection lawsuit is filed concerning a creditor's proposed distribution amount, and that amount is consequently deposited by the court, specific procedures follow. When the reason for the deposit ceases to exist (e.g., the distribution objection lawsuit is finally resolved), the court clerk is scheduled to make a "payment instruction" (支払委託 - shiharai itaku) regarding the deposited funds as part of implementing the distribution (Civil Execution Act Article 167, Paragraph 1; Article 166, Paragraph 2; Article 91, Paragraph 1, Item 7; Article 92, Paragraph 1; Civil Execution Rules Article 145, Article 61; Deposit Rules Article 30, Paragraph 1).

- Crucially, the Court held that until this payment instruction is made, the deposited funds cannot be said to have vested in the creditor who is to receive the distribution.

- Conclusion on "Termination" of Enforcement:

- Therefore, in such a case, the enforcement proceeding is not terminated merely when the court execution officer receives the proceeds from the sale under a sale order.

- It remains pending even after that point, and is only considered terminated when the payment instruction for the deposited funds is made.

- In this instance, debtor A's bankruptcy proceedings commenced before the payment instruction for the deposited funds was made (as C's distribution objection lawsuit against X was still pending).

- Thus, the enforcement proceeding initiated by X had not yet terminated. Consequently, Bankruptcy Act Article 42, Paragraph 2 (main text) applied, causing X's enforcement proceeding to lose its effect against A's bankruptcy estate.

The Supreme Court found that the lower court's judgment, which concluded that the enforcement court could ex officio cancel X's seizure order based on this lapse, was justifiable .

Commentary and Elaboration

1. Lapse of Enforcement upon Bankruptcy and Trustee's Options

- Prohibition of Individual Enforcement: A fundamental principle of Japanese bankruptcy law is that bankruptcy claims generally cannot be enforced outside the collective bankruptcy proceedings (Bankruptcy Act Article 100, Paragraph 1).

- Effect of Bankruptcy Commencement on Enforcement: When bankruptcy proceedings commence:

- No new enforcement actions based on bankruptcy claims can be initiated against property belonging to the bankruptcy estate (Bankruptcy Act Article 42, Paragraph 1).

- Existing enforcement proceedings already underway against such property lose their effect against the bankruptcy estate (Bankruptcy Act Article 42, Paragraph 2, main text).

- Rationale for Lapse: This lapse of enforcement is designed to prevent interference with the bankruptcy trustee's administration and disposal of the estate's assets for the benefit of all creditors.

- Consequences of Lapse: The lapse means the existing enforcement action retroactively loses its legal effect (though a buyer's title obtained through an enforcement sale is generally not undone). The seizing creditor loses all rights under that specific enforcement, such as the right to receive a distribution from the sale proceeds or to collect a seized monetary claim from a third-party debtor. The trustee can essentially ignore the lapsed enforcement and proceed with managing and disposing of the affected property.

- Trustee's Option to Continue Enforcement: However, the Bankruptcy Act (Article 42, Paragraph 2, proviso) allows the trustee to continue the lapsed enforcement proceedings if it is deemed beneficial for the bankruptcy estate (e.g., if the enforcement process is already well advanced and continuing it would be quicker or yield a better price than the trustee starting a new sale process). If continued, the proceeds of the liquidation are paid to the trustee and become part of the bankruptcy estate for distribution according to bankruptcy priorities, not through the original enforcement's distribution plan.

2. Lapse of Claim Enforcement and Practical Handling in Courts

- The lapse of enforcement effect occurs automatically by law upon the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings. The trustee does not need to take specific legal steps to cancel the existing enforcement orders (older court decisions have denied the trustee the ability to use execution law remedies to seek formal cancellation of lapsed enforcement).

- In the context of claim execution (e.g., seizure of a debt owed to the bankrupt by a third party):

- The trustee can disregard the seizure order and demand payment directly from the third-party debtor.

- If sale proceeds from an asset have been realized by the enforcement court but not yet distributed to creditors, the trustee can demand that the enforcement agency hand over these funds.

- If a seizing creditor receives a distribution after the enforcement has lapsed due to bankruptcy, the trustee can sue to recover these funds as unjust enrichment.

- Practical Court Procedures: Despite the automatic lapse, to provide clarity, particularly for third-party debtors in claim executions, the Tokyo District Court has an established practice. If the trustee informs the enforcement court of the bankruptcy commencement by submitting relevant documents (like a request for cancellation, termed jōshinsho), the enforcement court will ex officio issue an order cancelling the claim execution proceeding. This ex officio cancellation is a practical measure distinct from statutory grounds for stopping or cancelling execution (like Civil Execution Act Articles 39 or 40) and is generally accepted for the convenience of third parties. (The Osaka District Court follows a different practice: it confirms with the trustee whether they intend to continue the enforcement; if not, it notifies the parties that the enforcement has lapsed due to bankruptcy and then administratively closes the case file ).

3. When Does an Enforcement Proceeding "Terminate"?

- The lapse of enforcement under Bankruptcy Act Article 42, Paragraph 2 applies only if the enforcement proceeding is still pending when the debtor's bankruptcy proceedings commence. If the enforcement has already terminated before bankruptcy begins, Article 42, Paragraph 2 does not apply (it doesn't retroactively nullify a completed enforcement). Instead, the prior execution acts might become subject to the trustee's avoidance powers (e.g., Bankruptcy Act Article 165).

- Stages of Monetary Execution: Enforcement for monetary claims typically involves three stages: (1) seizure (差押え - sashiosae), (2) liquidation/conversion to money (換価 - kanka, e.g., sale), and (3) satisfaction (満足 - manzoku, e.g., distribution).

- Termination of the Entire Enforcement: The overall enforcement effort concludes when the creditor has received full satisfaction of their claim and execution costs, or when satisfaction becomes objectively impossible.

- Termination of an Individual Enforcement Procedure: An individual enforcement procedure (like a specific seizure and sale) ends when its final stage is completed, even if the creditor hasn't received full satisfaction. For monetary execution, this means the "distribution, etc." (配当等 - haitō tō, i.e., the distribution of proceeds or delivery of an allocated payment to the creditor) has been completed.

- In claim execution, this can also occur when the seizing creditor collects the debt from the third-party debtor (Civil Execution Act Art. 155) or when an assignment order (転付命令 - tempu meirei) or transfer order (譲渡命令 - jōto meirei) becomes effective (Civil Execution Act Art. 159, Para. 5; Art. 161, Para. 4).

- Application to Uncertificated Shares (as in this case):

- Execution against uncertificated shares (which are "other property rights") follows the rules for claim execution (Civil Execution Act Art. 167, Para. 1).

- Liquidation is typically by a court-issued "sale order" (売却命令 - baikyaku meirei) directing a court execution officer to sell the shares according to methods prescribed by the court (Civil Execution Act Art. 161, Para. 1).

- After the sale, the execution officer must promptly submit the sales proceeds to the enforcement court (Civil Execution Rules Art. 141, Para. 4).

- The enforcement court must then implement "distribution, etc." (Civil Execution Act Art. 166, Para. 1, Item 2).

- Therefore, the fundamental point of termination for this individual enforcement procedure is when the "distribution, etc." is completed.

4. The Distribution Procedure and "Distribution Reserve Deposit"

- The "distribution, etc." procedure is common to various types of execution. The enforcement court conducts distribution based on a "distribution table" (配当表 - haitōhyō) (Civil Execution Act Art. 84, Para. 1). On the distribution date, the court determines the distribution details (Art. 85, Para. 1), and the court clerk prepares the formal distribution table (Art. 85, Para. 5).

- Creditors or the debtor who are dissatisfied with the proposed distribution can file an objection on the distribution date (Art. 89, Para. 1).

- For amounts where no objection is made, the court must implement the distribution immediately, and for these portions, the distribution procedure (and thus the enforcement) concludes (Art. 89, Para. 2).

- If an objection is made, distribution of the contested amount is reserved. The objecting party must then file a "distribution objection lawsuit" within a specified period (Art. 90, Paras. 1 and 5).

- If such a lawsuit is filed, the court clerk must deposit the monetary equivalent of the contested distribution amount (Art. 91, Para. 1, Item 7). This is commonly called a "distribution reserve deposit" (haitō ryūho kyōtaku) and is considered a form of execution deposit. Importantly, making this deposit does not, in itself, extinguish the debtor's underlying debt.

- When the reason for the deposit ceases (e.g., the judgment in the distribution objection lawsuit becomes final and conclusive, or the suit is withdrawn, or the claim is abandoned/admitted, or a court settlement is reached), the enforcement court must implement "distribution, etc." from the deposited funds (Art. 92, Para. 1).

- This implementation of distribution from deposited funds is carried out by the court clerk issuing a "payment instruction" (shiharai itaku) (Civil Execution Rules Art. 61). Only after this payment instruction is made can the creditor, by submitting a payout request with necessary certificates to the deposit office (Deposit Rules Art. 30), actually receive the funds.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court reasoned, until the court clerk makes this "payment instruction," the deposited funds do not yet belong to the creditor; they remain part of the debtor's assets. Consequently, the distribution procedure, and by extension the entire enforcement proceeding concerning those funds, is not yet terminated.

5. Application to the Present Case

In X's case, when debtor A's bankruptcy proceedings commenced, creditor C's distribution objection lawsuit against X (and B) was still pending. The reason for the deposit of funds had not ceased, and the court clerk had not yet made any "payment instruction" for the funds allocated to X. Therefore, according to the Supreme Court's logic, the enforcement proceeding concerning X's claim on those funds had not terminated. As a result, Bankruptcy Act Article 42, Paragraph 2 (main text) applied, causing X's enforcement to lose its effect against A's bankruptcy estate.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2018 decision provides a crucial clarification on the exact point of termination for enforcement proceedings involving the sale of assets and subsequent distribution of proceeds, especially when distribution is complicated by objection lawsuits and the deposit of funds. By holding that such enforcement does not terminate until the court clerk issues a "payment instruction" for deposited funds, the Court has delineated a clear line. If a debtor's bankruptcy commences before this final step, the ongoing enforcement will lose its effect, ensuring that the assets involved are administered through the collective bankruptcy process rather than satisfying an individual creditor's claim. This reinforces the supremacy of bankruptcy proceedings in managing a debtor's assets once formal bankruptcy has begun.