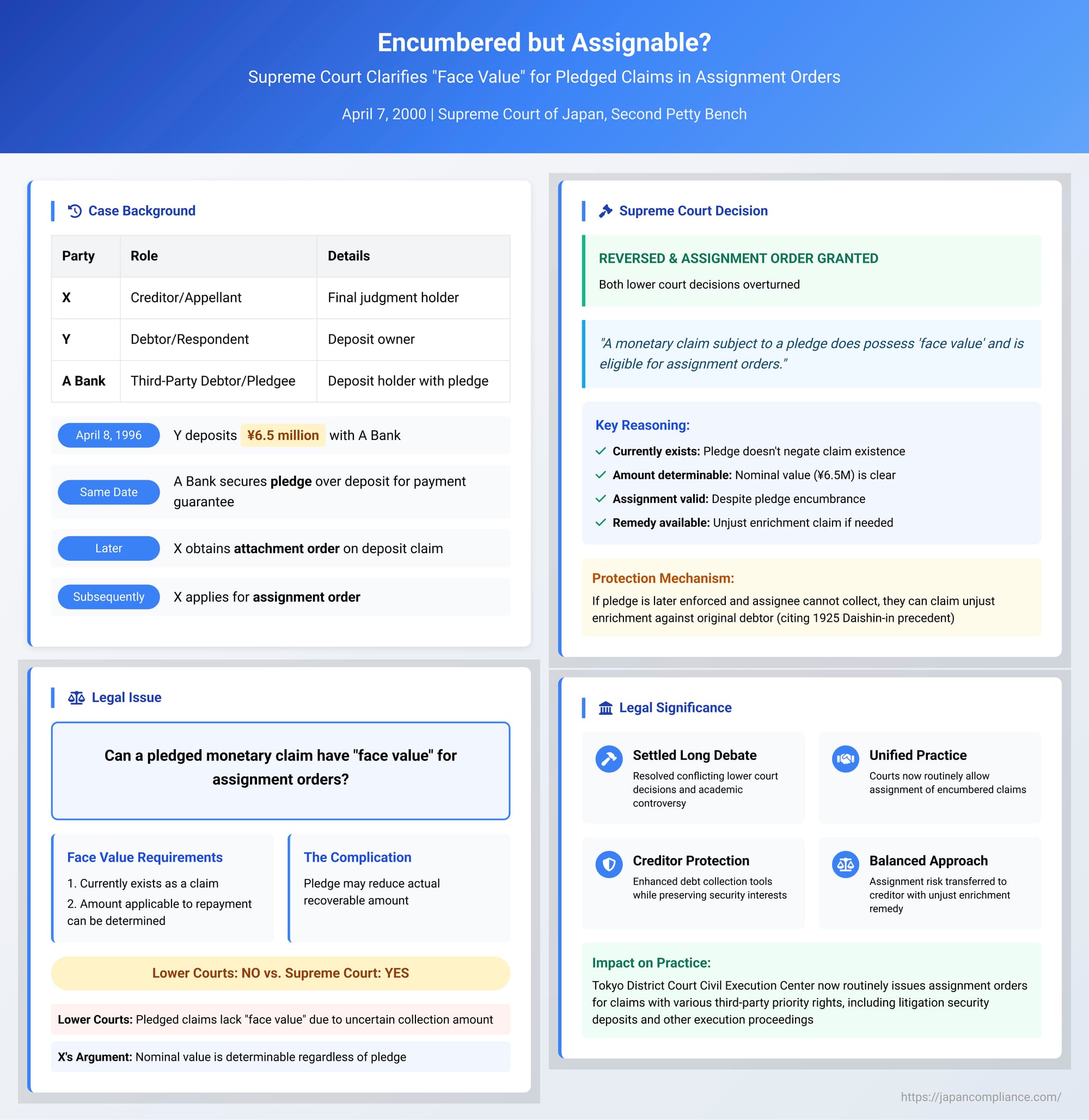

Encumbered but Assignable? Supreme Court Clarifies "Face Value" for Pledged Claims in Assignment Orders – A 2000 Decision

Date of Decision: April 7, 2000

Case Name: Appeal Against Dismissal of Execution Appeal Against Rejection of Assignment Order Application (Permitted Appeal)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: 1999 (Kyo) No. 42

Introduction

In Japanese civil execution proceedings, an "assignment order" (転付命令, tenpu meirei) is a significant remedy for a creditor. It allows the creditor to have a monetary claim owed by a third party to their debtor transferred directly to the creditor, in lieu of direct payment of the creditor's own claim against the debtor. For this powerful tool to be used, the law requires that the monetary claim being assigned possesses a "face value" (券面額, kenmengaku) – essentially, a determinable nominal monetary amount. This requirement ensures that the "payment" received by the creditor through the assignment is clear and immediate.

But what happens if the monetary claim targeted for assignment is already encumbered, for example, by a pledge granted to another party? Can such a claim still be considered to have the requisite "face value," or does the existence of the pledge render its ultimate collectible amount too uncertain? The Supreme Court of Japan provided a definitive answer to this long-debated question in its decision on April 7, 2000.

The Case of the Pledged Deposit: A Creditor, a Debtor, and a Bank

The factual background was as follows:

- X (Creditor/Appellant): Held a final judgment compelling Y to pay a sum of money.

- Y (Debtor/Respondent): Owed money to X under the judgment.

- A Bank (Third-Party Debtor/Pledgee): Held a time deposit belonging to Y.

The specifics of the claim in question:

Y had a claim for the refund of a JPY 6.5 million time deposit made with A Bank on April 8, 1996. This deposit was not a simple saving; it was linked to a "payment guarantee mandate contract" (支払保証委託契約, shiharai hoshō itaku keiyaku) that Y had entered into with A Bank. This contract, in turn, was established because Y was seeking a stay of compulsory execution in a separate legal dispute with X (Osaka High Court 1996 (U) No. 385). To secure any potential obligations Y might owe to A Bank arising from this payment guarantee, A Bank held a pledge (質権, shichiken) over Y's JPY 6.5 million time deposit claim.

X, armed with its judgment against Y, obtained an attachment order seizing this pledged time deposit claim. Subsequently, X applied to the Osaka District Court (acting as the execution court) for an assignment order to have this claim (Y's right to the JPY 6.5 million from A Bank) transferred to X.

The Lower Courts' Stance: No Assignment for Pledged Claims

- The Osaka District Court rejected X's application for an assignment order. It reasoned that granting such an order for a pledged claim would be "contrary to the purpose of an assignment order, which is the simple settlement of legal relations." The complexity introduced by the pledge was seen as an impediment.

- X appealed, but the Osaka High Court upheld the District Court's decision. The High Court focused on the "face value" requirement under Article 159(1) of the Civil Execution Act. It concluded that a monetary claim subject to a pledge does not have a "face value" because the actual amount that could eventually be collected by an assignee would depend on whether the pledge is exercised and for how much. This uncertainty, in the High Court's view, meant the claim was ineligible for an assignment order.

X then sought and was granted permission to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Reversal: Pledged Claims ARE Eligible for Assignment

The Supreme Court, on April 7, 2000, took a different view. It reversed the decisions of both lower courts. In a self-pronounced judgment, it canceled the order that had rejected X's assignment order application and proceeded to grant the assignment order to X for the pledged time deposit claim.

The Court's core reasoning was as follows:

- Existence of "Face Value" Despite Pledge: The Supreme Court directly addressed the "face value" issue for a monetary claim encumbered by a pledge:

- Such a claim undoubtedly "currently exists as a claim." The pledge does not negate the existence of Y's underlying claim against A Bank for the deposit.

- Furthermore, its "amount applicable to repayment can be determined." This refers to the nominal value of the claim (JPY 6.5 million in this case), which is clearly defined, even if the net amount realizable by the assignee might be affected by the pledge.

- Therefore, the Court concluded, such a pledged monetary claim does possess the "face value" required by Article 159(1) of the Civil Execution Act.

- Eligibility for Assignment Order: Consequently, a monetary claim is eligible to be the subject of an assignment order even if a pledge has been established over it.

- Addressing the Consequence of Pledge Enforcement: The Court proactively considered the scenario where, after an assignment order is issued and the attaching creditor's (X's) execution claim against their debtor (Y) is deemed satisfied up to the face value (as per Civil Execution Act Art. 160), the pledgee (A Bank) might subsequently enforce its pledge. This could lead to X (the assignee) being unable to receive full (or any) payment from A Bank on the assigned deposit claim.

- The Assignee's Recourse Against the Original Debtor: In such a situation, the Supreme Court clarified the legal recourse. If the pledge is enforced and X cannot collect the assigned JPY 6.5 million (or a part of it) because those funds were used to satisfy A Bank's secured claim against Y, it means that the claim acquired by X through the assignment order was, in effect, used to pay off Y's debt to A Bank. For the amount that X could not recover from A Bank due to the pledge execution, X (the assignee creditor) can then bring a claim against Y (their original debtor) for unjust enrichment (不当利得返還請求, futōritoku henkan seikyū). The Court cited a long-standing Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation – the predecessor to the Supreme Court) judgment from July 3, 1925 (Minshu Vol. 4, p. 613), in support of this unjust enrichment claim.

The Broader Legal Context and Impact of the Decision

This 2000 Supreme Court decision was significant because it resolved a long-standing debate in Japanese execution law and practice.

Understanding Assignment Orders and "Face Value":

- An assignment order is a mechanism where an attached monetary claim is transferred to the attaching creditor at its nominal "face value," and the creditor's original claim against the debtor is considered satisfied to that extent. This provides a route for potentially exclusive and immediate satisfaction for the creditor but also transfers the risk of the third-party debtor's insolvency (or other collection issues related to the assigned claim) to the creditor.

- The "face value" requirement is crucial because the system aims for a straightforward settlement of the creditor-debtor relationship.

The Historical Debate on Assigning Encumbered Claims:

- Problematic Claims for Assignment: Traditionally, legal scholars were often skeptical about the eligibility of certain types of claims for assignment orders due to "face value" concerns. These included:

- Future claims or claims subject to conditions precedent (e.g., future rent, security deposits before lease termination). (The Supreme Court itself had ruled against assignment for such claims in other cases).

- Claims requiring counter-performance from the debtor.

- And, central to this case, claims subject to the priority rights of others, like pledges.

- Pledged Claims Specifically:

- The Daishin-in had affirmed the assignability of pledged claims back in 1925. Several lower court decisions followed this positive view.

- However, a contrary line of lower court judgments also existed, including the High Court decision in the present case, which denied assignability.

- Academic opinion was largely against allowing assignment orders for pledged claims. The main reasons cited were: (1) the potential for the pledge to be enforced, thereby reducing the value of the assigned claim, meaning its "face value" was not truly fixed for repayment purposes; and (2) the subsequent need for unjust enrichment claims complicated the "immediate settlement" ideal of an assignment order.

- Proponents of assignability argued that: (1) even supposedly "clear" claims can face disputes about their amount after assignment; (2) assignment does not harm the pledgee's superior rights; and (3) any risk associated with the pledge is a matter for the attaching creditor's strategic calculation and does not unfairly prejudice the original debtor (who, after all, created the situation by not paying their debt and by pledging their asset).

- Practical Court Guidance: Influenced by academic skepticism, some major execution courts in Japan had reportedly adopted a practice of discouraging applications for assignment orders against pledged monetary claims.

The Supreme Court's 2000 Resolution:

The Supreme Court's decision cut through this debate. By affirming the two prongs for "face value" – that the pledged claim "currently exists" and its "amount applicable to repayment can be determined" (referring to its nominal value) – the Court established a clear rule. The fact that the pledgee's actions might later reduce the actual amount collected by the assignee does not negate the claim's initial eligibility for assignment based on its nominal value. The mechanism of an unjust enrichment claim against the original debtor provides the necessary subsequent adjustment if the assignee's recovery is impaired by the pledge.

Impact of the Decision:

- Clarity and Uniformity: This ruling brought much-needed clarity and settled the conflicting case law, establishing a unified approach to the assignability of pledged monetary claims.

- Established Practice: It has since solidified court practice. Execution courts, like the Tokyo District Court Civil Execution Center, now routinely issue assignment orders for claims subject to various third-party priority rights, not limited to pledges, such as rights to recover funds deposited as security in litigation or other execution proceedings.

- Further Issues: A subsequent Supreme Court decision in 2003 addressed a related question: whether a creditor who obtained an assignment order for a pledged claim could then apply for the cancellation of the security arrangement that gave rise to the pledge (the answer was no, the assignee doesn't automatically step into all of the debtor's rights related to the creation of the pledge).

Conclusion: Pragmatism in Balancing Creditor Rights and Secured Transactions

The Supreme Court's April 7, 2000, decision represents a pragmatic approach to a complex issue in debt execution. It affirms the utility of assignment orders as a means for creditors to obtain satisfaction, while acknowledging the realities of secured transactions like pledges. By allowing the assignment of pledged claims based on their nominal "face value" and providing a clear path for recourse (via unjust enrichment) if the pledge later diminishes the assignee's recovery, the Court struck a balance. It ensures that the existence of a pledge does not automatically shield an otherwise attachable monetary claim from this effective form of execution, while also ensuring that the ultimate financial consequences are fairly allocated between the creditor and their original debtor. This ruling has significantly shaped the landscape for creditors seeking to enforce judgments against assets that may be subject to prior encumbrances.