Empty Coffers, Phantom Capital: Japan's Supreme Court on Disguised Share Payments

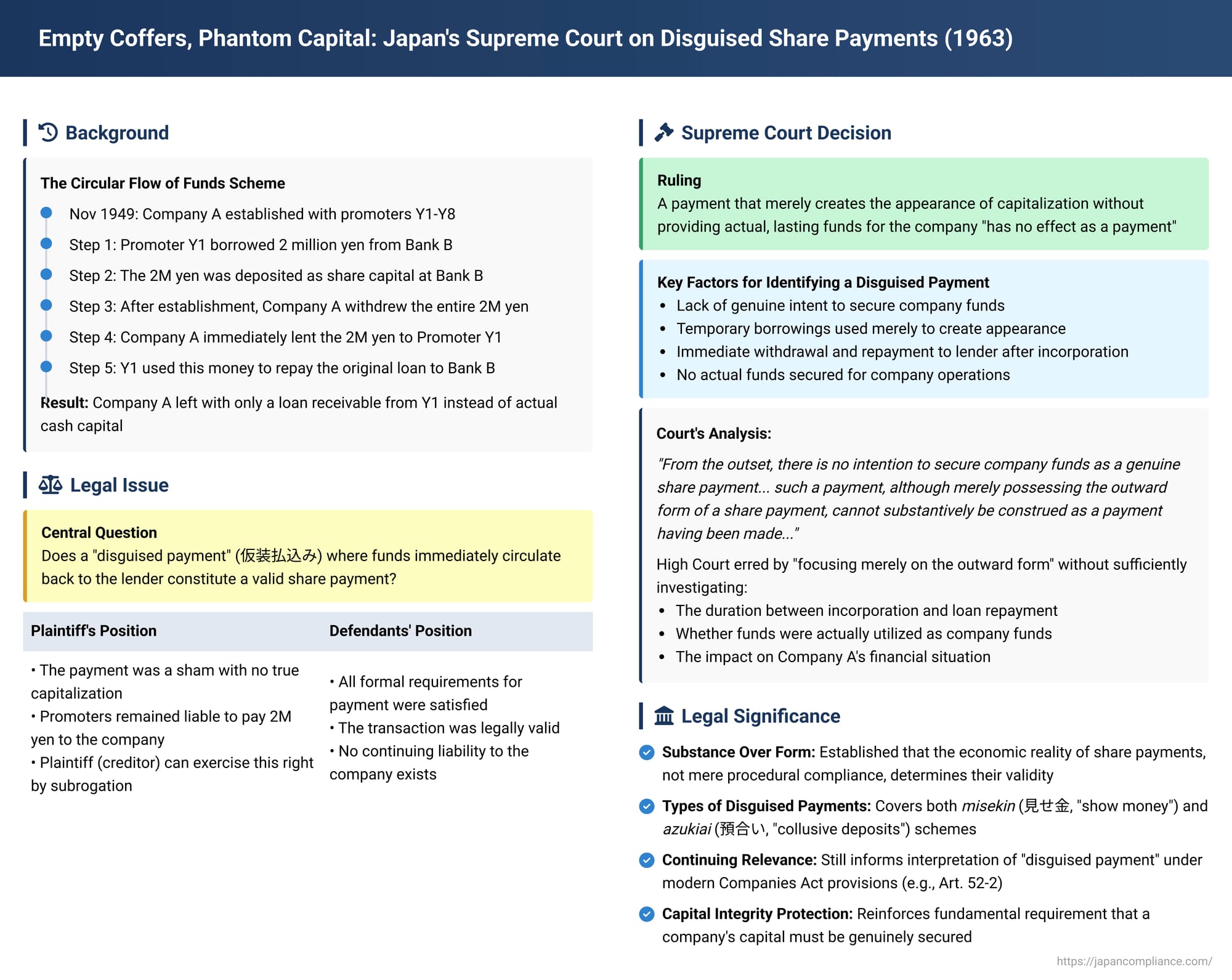

The financial health and integrity of a company begin with its initial capitalization. When shareholders subscribe for shares, the law expects a genuine infusion of funds to provide the company with the resources it needs to operate and meet its obligations. However, history has seen various schemes designed to merely create the appearance of capitalization without any real, lasting contribution. Such "disguised payments" (仮装払込み - kasō harai komi) undermine the corporate system. A Japanese Supreme Court decision on December 6, 1963, addressed this critical issue, establishing that the substance, not just the form, of share payments determines their validity.

The Facts: A Circular Flow of Funds

The case involved the establishment of Company A, a joint-stock company, which was registered on November 5, 1949. The defendants, Y1 through Y8, were the promoters of Company A. To fulfill their obligation to pay for the shares they subscribed to during the incorporation process, a specific financial arrangement was made. Promoter Y1, acting as the principal debtor, along with the other promoters acting as joint guarantors, borrowed 2 million yen from Bank B.

This borrowed sum of 2 million yen was then deposited into Bank B, which was also the designated bank for handling Company A's share capital payments. On paper, this appeared as a full payment of the initial share capital. Promoter Y1 obtained a certificate of deposit of paid-in capital from Bank B, a crucial document for completing the company's incorporation registration.

Once Company A was formally established, the sequence of events that drew scrutiny unfolded:

- Company A withdrew the entire 2 million yen (its supposed paid-in capital) from Bank B.

- Company A immediately lent this same 2 million yen to Promoter Y1.

- Promoter Y1 then used this 2 million yen, which he had just received as a loan from Company A, to repay the initial 2 million yen loan he had taken from Bank B.

Essentially, the money made a round trip: from Bank B (as a loan to promoters) -> to Bank B (as share capital for Company A) -> from Bank B (as a withdrawal by Company A) -> to Promoter Y1 (as a loan from Company A) -> back to Bank B (as repayment of the promoters' initial loan). The net result was that Company A was left with a loan receivable from its lead promoter instead of actual cash capital, while the promoters' debt to the bank was settled using what was notionally the company's capital.

The plaintiff, X (the State, as legal successor to a public corporation named C Public Corporation), held an unpaid accounts receivable claim against Company A. Discovering that Company A lacked the assets to satisfy this debt, Plaintiff X sued Promoters Y1-Y8, seeking payment of 2 million yen.

The plaintiff's core argument was that the promoters' payment for Company A's shares was a "disguised payment" (kasō harai komi). In substance, no real, lasting capital contribution of 2 million yen had been made to Company A. Therefore, Plaintiff X contended, Promoters Y1-Y8, as promoters, remained jointly and severally liable to pay 2 million yen to Company A under the provisions of the then-Commercial Code (Article 192, Paragraph 2), which imposed a liability on promoters to ensure full payment for subscribed shares. Since Company A itself was not pursuing this claim against its own promoters, Plaintiff X was exercising this right in subrogation (acting on behalf of Company A to enforce its claim against the promoters).

Lower Court Disagreement

The first instance court found in favor of Plaintiff X, accepting the argument that the payment was disguised and that the promoters were liable. However, the High Court reversed this decision, dismissing Plaintiff X's claim. The High Court reasoned that the transaction, as described, could not immediately and definitively be judged as a disguised payment lacking legal effect.

The Supreme Court's Stance on Disguised Payments

The Supreme Court, in its Second Petty Bench judgment, overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further examination. The Court's reasoning provided a clear definition of disguised payments and their legal ineffectiveness.

1. Purpose of Share Payments:

The Court began by emphasizing the fundamental purpose of paying for shares: "to ensure the adequacy of capital, which is the foundation for a joint-stock company's business activities upon its establishment." Therefore, "funds for business activities must actually be acquired through this process." This principle, the Court noted, was underscored by numerous provisions in the Commercial Code designed to ensure the reality of such payments.

2. Definition and Ineffectiveness of Disguised Payments:

The Supreme Court then directly addressed the nature of disguised payments:

"Therefore, in cases such as when, from the outset, there is no intention to secure company funds as a genuine share payment, and temporary borrowings are used merely to create the outward appearance of payment, and immediately after the procedures for establishing the joint-stock company are completed, said paid-in funds are withdrawn and repaid to the lender, the said company's operating funds are in no way secured. Such a payment, although merely possessing the outward form of a share payment, cannot substantively be construed as a payment having been made, and it must be said that it has no effect as a payment."

3. Key Factors for Identifying a Disguised Payment:

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had not sufficiently investigated the facts to determine if this was indeed a disguised payment. It pointed to several critical factors that needed closer examination, the outcome of which could lead to the suspicion that the payment was merely a sham intended to feign capitalization without any genuine intent to fund the company, thus rendering it ineffective as a share payment:

* The duration of time between Company A's establishment and Promoter Y1's repayment of the initial loan to Bank B using funds withdrawn from Company A.

* Whether the withdrawn funds were, in fact, utilized as company funds for any period, however short.

* The impact of the loan repayment (by Promoter Y1 to Bank B, using Company A's funds) on Company A's overall financial situation.

The Court observed that the record even suggested that the repayment of Promoter Y1's loan to Bank B occurred very shortly after Company A's establishment, indicating that the paid-in capital was not substantively secured as company funds.

4. Error of the High Court:

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court, by "focusing merely on the outward form of the share payment in this case and recognizing it as a valid payment, thereby denying the liability of Defendants Y1-Y8 for the share payment, without fully deliberating on such circumstances and consequently without indicating any special circumstances," committed an error of "insufficient deliberation and inadequate reasoning." This error clearly affected the judgment, necessitating its reversal and remand for a more thorough factual investigation based on the principles laid down by the Supreme Court.

Understanding "Disguised Payments" (Kasō Harai Komi)

This Supreme Court decision is a cornerstone in understanding the legal treatment of disguised payments for shares in Japan. The PDF commentary provides further context on different forms this can take:

- "Misekin" (見せ金 - literally "show money" or "display money"): This typically involves a promoter borrowing funds from a third party (i.e., not the bank designated to handle share payments), using these borrowed funds to make the formal share payment into the designated bank, and then, after the company is established and the promoter becomes a director, quickly arranging for the company to withdraw those funds and lend them back to the promoter (or otherwise return them), who then uses them to repay the initial third-party loan. While each individual step (borrowing, paying in, company lending to a director) might appear formally valid if proper procedures are followed, the overall orchestrated scheme lacks the genuine intent to capitalize the company. The majority view in legal scholarship is that such a scheme, viewed holistically, does not constitute a valid payment because the funds are never truly intended for the company's use. Fairness among subscribers who make genuine contributions also supports this conclusion.

- "Azukiai" (預合い - often translated as "collusive deposit" or "offsetting deposit"): This form typically involves collusion between the promoter and the bank designated to handle the share payments. The promoter might "borrow" from the handling bank itself, or there might be an understanding that funds ostensibly paid in will not actually be available for the company to withdraw until the promoter fulfills some other obligation to the bank (e.g., repays a separate loan). Often, azukiai might involve mere bookkeeping entries within the bank without any actual funds being advanced to or controlled by the promoter before being "paid in." This practice is also subject to criminal penalties under the Companies Act (Article 965), and it is generally undisputed that azukiai does not constitute an effective share payment. However, a complicating factor is Article 64, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act (and similar preceding provisions), which stipulates that a bank, having issued a certificate of deposit for paid-in capital, cannot assert against the company any restrictions on the repayment of those funds (such as a non-withdrawal agreement). This provision aims to ensure the company can access the certified funds.

The specific facts of the 1963 Supreme Court case—where the promoters borrowed from the same bank that handled the share payments, but there was an actual movement of funds (loan to promoters, deposit by promoters, withdrawal by company, loan by company to promoter, repayment by promoter to bank)—are considered an "intermediate form" between a classic misekin and a classic azukiai. However, if both forms are ultimately deemed ineffective as payments, the precise categorization is less critical than the overarching principle of identifying and invalidating payments that are merely a pretense.

Legal Consequences and Liabilities

The Supreme Court's ruling that a disguised payment "has no effect as a payment" has significant consequences:

- Continuing Obligation of Subscriber: If the payment is ineffective, the subscriber (in this case, the promoters) is deemed not to have fulfilled their obligation to pay for the shares. They would, in principle, still owe this amount to the company.

- Promoters' Liability (Historical and Current):

- At the time of this judgment, the Commercial Code (Article 192, Paragraph 2) imposed a "payment guarantee liability" (払込担保責任 - haraikomi tanpo sekinin) on promoters and directors involved in the establishment, making them jointly and severally liable to ensure that all subscribed shares were fully paid for. This was the basis of Plaintiff X's claim in subrogation. This specific form of liability was abolished with the enactment of the Companies Act in 2005.

- However, the Companies Act, particularly after amendments in 2014, introduced new, explicit provisions addressing disguised payments. Promoters or subscribers who make a disguised payment are now directly obligated to pay the full disguised amount to the company (e.g., Companies Act Article 52-2, Paragraph 1; Article 102-2, Paragraph 1).

- Furthermore, promoters, directors at the time of incorporation, or other similar executives who were involved in the disguised payment are also jointly and severally liable to the company for that amount, unless they can prove they were not negligent (e.g., Companies Act Article 52-2, Paragraphs 2 and 3; Article 103, Paragraph 2).

- The Companies Act itself does not specifically define "disguised payment." Therefore, the criteria and reasoning laid out in the 1963 Supreme Court judgment remain highly relevant for determining what constitutes a disguised payment under the current law.

The Status of Shares Issued via Disguised Payments

A complex related issue is the legal status of shares for which a disguised payment was made. If the payment is ineffective, does this mean the shares themselves are void or that the subscriber automatically forfeits them (shikken - 失権)?

- The PDF commentary discusses a somewhat mixed history in Supreme Court jurisprudence on this, potentially influenced by the existence of formal forfeiture procedures at the company establishment phase versus their absence (under older law) for post-incorporation share issuances, and the backdrop of the (now abolished) directors' payment guarantee liability.

- The 2014 amendments to the Companies Act introduced provisions that shed more light on the current approach. A person who made a disguised payment cannot exercise shareholder rights related to those shares until they fulfill their payment obligation to the company (e.g., Article 52-2, Paragraph 4). However, if these shares are transferred to a third party who acquires them in good faith and without gross negligence, that third party can exercise shareholder rights, even if the original payment obligation has not been met (e.g., Article 52-2, Paragraph 5).

- These current provisions strongly suggest that even if a payment is disguised, the shares themselves are considered to be validly issued to the subscriber, and the subscriber does not automatically forfeit them. Instead, their rights are suspended until genuine payment is made, and bona fide purchasers are protected. This contrasts with a stricter view that might deem the shares unissued or the subscriber to hold only a kind of option to acquire them upon actual payment.

- There remains an academic debate on whether a disguised payment can be grounds for a lawsuit to invalidate the issuance of new shares, particularly to prevent shares from being effectively laundered through a transfer to a bona fide third party. Some argue for this possibility, while others contend that disguised payment, being a defect related to individual shares rather than the entire share issuance process, should not typically lead to the invalidation of the entire issuance, drawing parallels with how issues like payment shortfalls for contributions in kind are handled.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1963 decision in this case involving disguised share payments delivered a clear message: legal formalities alone cannot mask a substantive failure to capitalize a company. By focusing on the genuine intent to provide lasting funds for the company's operations and scrutinizing the actual flow and use of money, the Court established that payments designed merely to create an illusion of capital are ineffective. This judgment underscored the importance of substance over form in ensuring the integrity of the corporate capitalization process. While specific statutory provisions regarding promoter and director liability have evolved, the core principles articulated in this ruling for identifying a "disguised payment" continue to inform the interpretation and application of current Japanese company law, reinforcing the fundamental requirement that a company's capital must be genuinely and substantively secured.