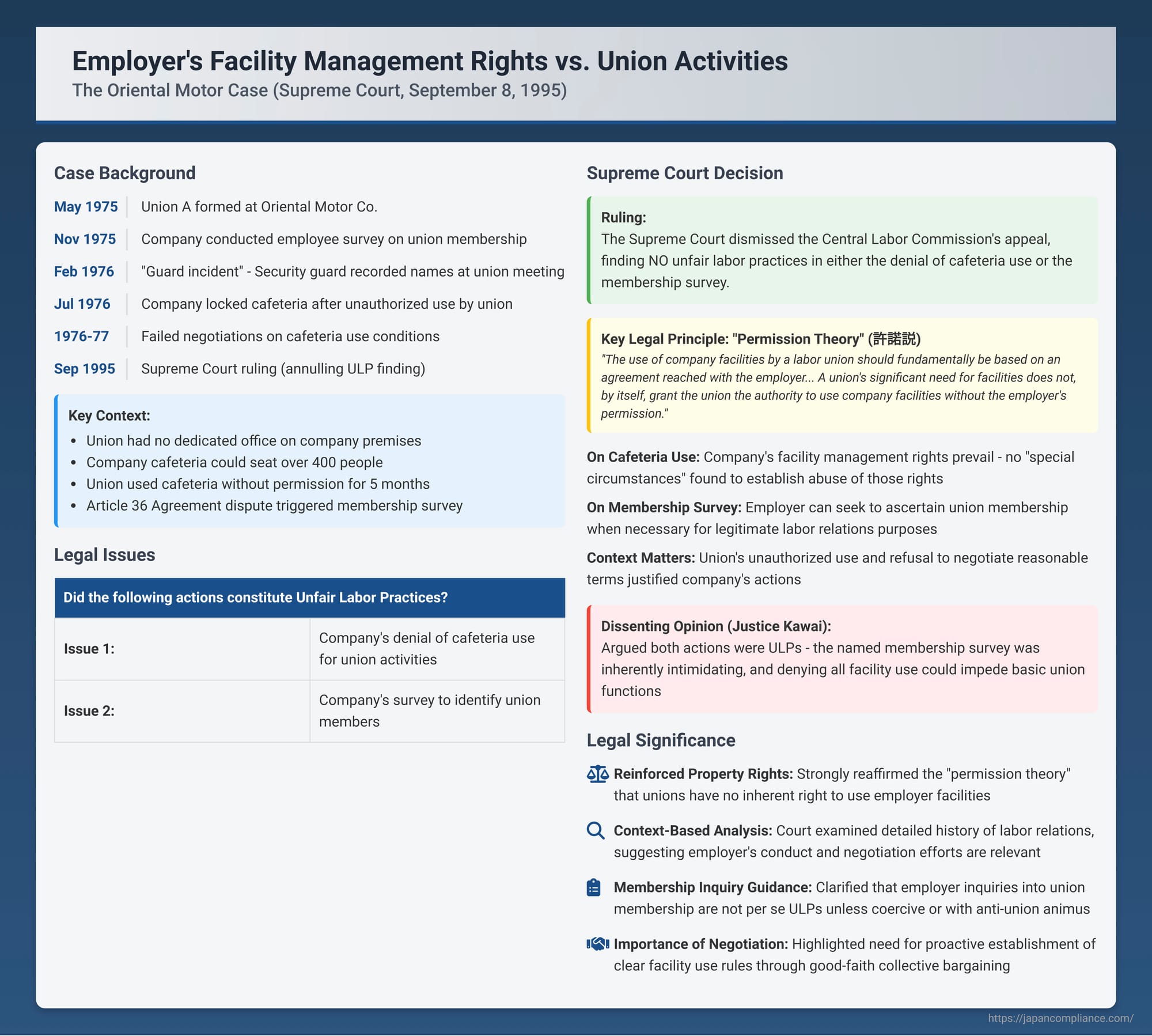

Employer's Facility Management Rights vs. Union Activities: The Oriental Motor Case (Supreme Court of Japan, September 8, 1995)

On September 8, 1995, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in the Oriental Motor case. This case delved into the complex interplay between an employer's right to manage its facilities and a labor union's need to use those facilities for its activities, specifically addressing when an employer's refusal of such use, or its inquiries into union membership, might constitute an unfair labor practice (ULP) of domination or interference.

Case Reference: 1991 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 34 (Petition for Rescission of Unfair Labor Practice Remedy Order)

Appellant (Original Plaintiff): Company X (Oriental Motor Co., Ltd.)

Appellee (Original Defendant): Central Labor Commission

Appellee-Intervenor: Union A (All Japan Metal and Information Equipment Workers' Union, Tokyo Regional Headquarters, Oriental Motor Branch)

Judgment of the Supreme Court: The original judgment (High Court) was partially overturned. The Supreme Court annulled the Central Labor Commission's findings of unfair labor practices concerning both the denial of cafeteria use and the employee survey.

Factual Background: A Strained Relationship

The dispute unfolded against a backdrop of evolving labor-management relations at Company X, a manufacturing company.

- Initial Cooperation and Unresolved Issues: Union A, an enterprise union representing Company X's employees, was formed and officially notified Company X in May 1975. Initial negotiations led to a basic understanding that Company X would provide a union office within its premises, though a formal agreement on specifics like location was never finalized.

- Cafeteria Use - Early Practice: The company's employee cafeteria (seating over 400) was made available for Union A's use upon request, provided it did not interfere with Company X's operations.

- The "Guard Incident" and its Aftermath: On February 23, 1976, during a union study session in the cafeteria (for which permission had been granted), a company security guard began recording the names of attendees. Union A protested this as interference. In response, Company X warned the union against obstructing guard duties and stated that if Union A persisted in calling such security measures "interference," all company facility use by the union would be denied. Subsequently, Union A began using the cafeteria without seeking permission, submitting altered forms as "notifications" rather than "requests." This unauthorized use continued for nearly five months until July 1976, when Company X installed a door on the cafeteria and locked it, preventing further access by the union.

- Failed Negotiations on Cafeteria Use: Between March 1976 and July 1977, there were intermittent document exchanges and negotiations, partly mediated by the Chiba District Labor Commission. Company X's proposal on March 18, 1976, offered to permit cafeteria use for union general meetings if Union A agreed to certain conditions (e.g., submitting a detailed permission request in advance, specifying purpose, attendees, and time). Union A's counter-proposals were viewed by Company X as ignoring its fundamental facility management rights. Negotiations broke down.

- The Union Membership Survey: Separately, in November 1975, an issue arose concerning an "Article 36 Agreement" (a labor-management agreement required under the Labor Standards Act to legitimize overtime and holiday work). The existing agreement's validity was questioned by the Labor Standards Inspection Office. Union A demanded that Company X conclude a new Article 36 Agreement with it, claiming to represent a majority of employees. Company X requested Union A to submit its membership list to verify this majority status, but the union refused. Consequently, on November 18, 1975, Company X distributed a questionnaire (inquiry form) to all employees during working hours, requiring them to state their union affiliation with their names and return it immediately.

Rulings of Labor Commissions and Lower Courts

- Labor Commissions: The Chiba District Labor Commission, and subsequently the Central Labor Commission (CLC) upon review, found that Company X's actions constituted unfair labor practices.

- Cafeteria Use: Excluding Union A from using the cafeteria was deemed a ULP. The CLC ordered Company X to generally permit Union A to use the cafeteria for its branch and chapter meetings (unless the company had special reasons for needing it itself) and to negotiate in good faith with Union A regarding cafeteria use for other union meetings.

- Membership Survey: Distributing the questionnaire to ascertain union membership was also found to be a ULP (domination or interference). The CLC ordered Company X not to interfere with union administration by inquiring about employees' union affiliation and to post a notice to that effect (a "post-notice" remedy).

- Tokyo District Court: Company X sought to annul the CLC's order. The District Court sided with Company X, finding no abuse of facility management rights and thus no ULP concerning cafeteria use, and presumably also found the survey permissible.

- Tokyo High Court: The CLC appealed. The High Court reversed the District Court's decision. It held that denying all cafeteria use to Union A, especially when no dedicated union office had been provided, made it extremely difficult for the union to conduct its activities and amounted to an abuse of facility management rights, thus constituting a ULP. It upheld the CLC's order regarding cafeteria use. (The provided summary is less explicit about the High Court's reasoning on the survey, but the Supreme Court addresses both).

Company X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's ruling, ultimately finding in favor of Company X on both ULP claims. There was a dissenting opinion from Justice Shinichi Kawai.

I. General Principles Regarding Union Use of Company Facilities and ULP

The Court first laid out general principles:

- Need vs. Right: Enterprise unions (unions composed solely of a company's employees) understandably rely heavily on company facilities for their activities. However, this need does not translate into an inherent, legally guaranteed right for a union to use company-owned and managed facilities.

- Basis of Use: Agreement: The use of company facilities by a labor union should fundamentally be based on an agreement reached with the employer, typically through collective bargaining or similar discussions.

- No Employer Duty to Tolerate Unauthorized Use: A union's significant need for facilities does not, by itself, grant the union or its members the authority to use company facilities for union activities without the employer's permission. Correspondingly, it does not impose an obligation on the employer to tolerate such unauthorized use.

- Unauthorized Use as Infringement: Unauthorized use of company facilities for union activities infringes upon the employer's authority to manage and utilize its facilities and disrupts corporate order. Such use is not considered a legitimate union activity, unless denying permission constitutes an abuse of the employer's facility management rights under special circumstances. This aligns with the "permission theory" (kyodaku-setsu) previously established by the Court.

- Refusal as ULP: While an employer's refusal to allow union use of its facilities, if intended to weaken the union, can constitute a ULP, the decision to grant or deny permission is, in principle, left to the employer's free judgment. Therefore, merely not granting permission does not automatically infringe upon the right to organize or constitute a ULP, absent an abuse of rights under special circumstances.

II. Application to the Cafeteria Use Dispute

Applying these principles, the Court found:

- Company X's prior practice of permitting cafeteria use for about nine months did not constitute an irrevocable, comprehensive grant of permission that it could not later modify.

- Union A's subsequent actions – altering official permission forms into mere "notifications" and using the cafeteria without Company X's explicit consent for nearly five months – clearly disregarded Company X's facility management rights and were not legitimate union activities.

- Company X's proposed conditions for cafeteria use (requiring proper applications, limiting external attendees for general meetings, ensuring non-exclusive use) were deemed reasonable from a facility manager's standpoint and not merely a pretext.

- Conversely, Union A's counter-proposals were seen as understating Company X's facility management rights, almost presuming an inherent right for the union to use the cafeteria. Given the history of unauthorized use, Company X's perception that its rights were being ignored was understandable.

- Therefore, Company X's decision to change its previous practice following the "guard incident," its attempt to establish reasonable rules based on its facility management rights, and its subsequent refusal to allow cafeteria use when Union A continued to disregard these rights and no agreement on conditions could be reached, were considered "unavoidable."

The Court concluded that even considering factors like the cafeteria's nature (where union use might cause less operational disruption than other facilities), the union's lack of a dedicated office, and Company X's rejection of Labor Commission recommendations, there were no "special circumstances" to deem the continued refusal of cafeteria use an abuse of Company X's rights. Nor could it be definitively concluded that Company X's actions were intended to weaken Union A. Thus, the refusal to permit cafeteria use did not constitute a ULP.

III. Application to the Union Membership Survey Dispute

The Court also overturned the ULP finding regarding Company X's survey of employee union affiliation:

- No General Union Duty to Disclose Members: Unions are generally not obligated to provide employers with their membership lists.

- Employer's Need to Know vs. Interference: An employer seeking to know which of its employees are union members is not, in itself, prohibited. Such information can be necessary for legitimate labor relations purposes, such as concluding collective agreements or during wage negotiations.

- When Inquiry Becomes ULP: An inquiry into union membership could constitute domination or interference if conducted under circumstances suggesting that union members might face concrete disadvantages, or if it's done with the intent to cause unrest among union members. However, merely attempting to ascertain membership is not generally a ULP.

- Context of the Survey: In this case, Company X urgently needed to conclude a new Article 36 Agreement because the Labor Standards Inspection Office had raised concerns about the existing one, leading to a halt in overtime work. Union A, while demanding to be the party to the new agreement (claiming majority status), repeatedly refused to provide its membership list to verify this.

- Reasonableness of the Method: Given the union's lack of cooperation and the company's legitimate need to ascertain the union's representation rate for the Article 36 Agreement, the Court found that Company X's decision to use a named questionnaire to ensure accuracy was not necessarily unreasonable or improper, especially if it believed an anonymous survey might not yield reliable results. The Court stated that merely because the survey was not an anonymous ballot did not automatically mean it was intended to intimidate members or weaken the union.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that distributing the questionnaire under these circumstances did not constitute a ULP.

Analysis and Significance

The Oriental Motor decision is a key judgment in understanding the balance between employer property rights and union activity rights in Japan.

- Reinforcement of the "Permission Theory": The judgment strongly reaffirms the Supreme Court's established "permission theory" (kyodaku-setsu) concerning union use of company facilities. This theory posits that unions do not possess an inherent right to use an employer's premises for their activities; such use is contingent upon the employer's permission. Unauthorized use is generally considered illegitimate unless the employer's denial of permission amounts to an "abuse of rights" under "special circumstances." This contrasts with the "toleration duty theory" (junin gimu setsu), which suggests employers might have a duty to tolerate facility use for legitimate union activities.

- Facility Management Rights Prevail Absent Abuse: The employer's facility management right is paramount. Unless the union can demonstrate "special circumstances" where denying access constitutes an abuse of this right, or that the employer's refusal is motivated by an intent to weaken the union, the employer's decision to refuse facility use will generally not be deemed an unfair labor practice. While the Court denied abuse in this instance, its detailed examination of the labor relations history implies that the employer's conduct and negotiation efforts are relevant factors.

- Guidance on Union Membership Inquiries: The Court provided nuanced guidance on employer inquiries into union membership. Such inquiries are not per se ULPs. They become problematic if carried out in a coercive atmosphere or with anti-union animus. The employer's legitimate need for the information (e.g., to verify majority status for an Article 36 Agreement) and the union's cooperativeness (or lack thereof) are important considerations in assessing the propriety of the inquiry method. The dissenting opinion, however, viewed the on-the-spot, named survey as inherently intimidating.

- Emphasis on Rule-Making through Negotiation: The case indirectly highlights the importance for both employers and unions to proactively establish clear rules regarding union use of company facilities through good-faith collective bargaining. This can prevent disputes like the one in Oriental Motor from escalating.

- Ongoing Debate: The presence of a strong dissenting opinion by Justice Kawai on both ULP claims underscores the continuing debate and differing judicial philosophies regarding the appropriate balance between employer prerogatives and the protection of union rights in the workplace.

Conclusion

The Oriental Motor Supreme Court judgment solidifies the "permission theory" as the guiding principle for union use of company facilities in Japan. It places a strong emphasis on the employer's facility management rights, allowing refusal of union use unless such refusal constitutes an abuse of rights under special circumstances or is driven by anti-union intent. Similarly, inquiries into union membership are not automatically ULPs but are assessed based on their context, purpose, and potential impact on employees' right to organize. The decision underscores the judiciary's approach of detailed factual analysis in ULP cases, while also highlighting the persistent legal debate over how best to balance managerial rights with robust protection for union activities.