Employer's Duty of Neutrality in a Multi-Union Workplace: The Nissan Motor Case (Supreme Court of Japan, April 23, 1985)

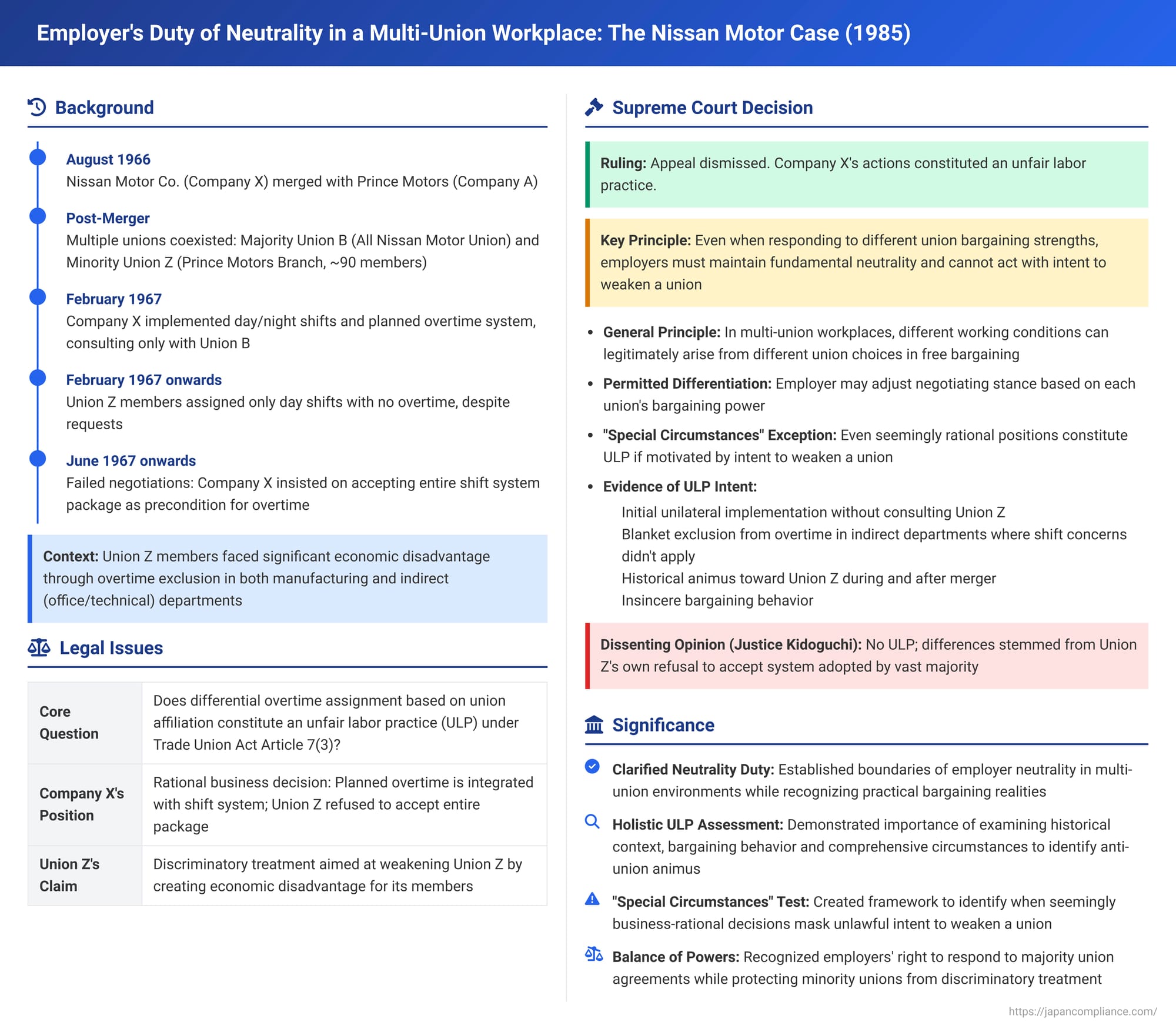

On April 23, 1985, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment in the Nissan Motor Co. case. This case profoundly addressed the obligations of an employer in a workplace where multiple labor unions coexist, particularly focusing on the employer's duty of neutrality and how differential treatment of unions in working conditions, specifically overtime assignments, can constitute an unfair labor practice (ULP).

Case Reference: 1978 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 40 (Petition for Rescission of Unfair Labor Practice Remedy Order)

Appellant (Original Plaintiff): Company X (Nissan Motor Co., Ltd.)

Appellee (Original Defendant): Central Labor Commission

Appellee-Intervenors: Union Z (National Trade Union of Metal and Engineering Workers, Prince Motors Branch, and its parent organizations)

Judgment of the Supreme Court: The appeal by Company X is dismissed. The appellant shall bear the court costs.

Factual Background: Merger, Multiple Unions, and Differential Treatment

The dispute arose in the wake of Company X's absorption of Company A (Prince Motors, Ltd.) in August 1966.

- Coexisting Unions: Following the merger, two main unions existed within Company X: Union B (the All Nissan Motor Labor Union), which was the majority union, and Union Z (the Prince Motors Branch of the National Trade Union of Metal and Engineering Workers), a minority union. Union Z had been the primary union at the former Company A, but many of its members joined the larger Union B after the merger. At the time of the Central Labor Commission's review, Company X had approximately 53,000 employees, of whom only about 90 were members of Union Z, with the vast majority belonging to Union B.

- New Work System: From February 1967, Company X implemented a day/night shift system and a "planned overtime" system in the manufacturing departments of the former Company A plants. This system was already in place in Company X's original manufacturing divisions. Crucially, Company X consulted only with the majority Union B before introducing this new system; Union Z was not consulted.

- Differential Overtime Assignment: Under the new system, only members of Union B were integrated into the day/night shift rotations and were consistently assigned planned overtime (typically 1-2 hours daily and some weekend work). In contrast, members of Union Z were exclusively assigned to day shifts and were not given any overtime assignments at all. This practice extended to indirect departments (office and technical staff) as well, where Union Z members were also denied overtime from February 1967, while Union B members received it based on operational needs.

- Failed Negotiations with Union Z: Starting June 1967, Union Z requested that its members also be assigned overtime. During ensuing collective bargaining sessions, Company X maintained that the day/night shift system and planned overtime were an integrated package. It asserted that unless Union Z agreed to this entire system, as Union B had, Union Z members could not be included in planned overtime. Union Z, while expressing willingness for its members to work overtime, was principally opposed to night shifts under the existing conditions and proposed alternatives (e.g., a five-day work week, slower conveyor belt speeds during night shifts, increased night shift allowances). These negotiations ultimately failed.

The ULP Claim and Lower Court Rulings

Union Z filed an unfair labor practice claim, arguing that Company X's refusal to assign overtime to its members constituted discrimination aimed at weakening their union (a ULP under Article 7(3) of the Trade Union Act – domination or interference).

- Labor Commissions: The Tokyo Metropolitan Labor Commission, and subsequently the Central Labor Commission (CLC) on review, found that Company X had committed a ULP. They ordered Company X to cease discriminating against Union Z members in the assignment of overtime based on their union affiliation.

- Tokyo District Court: Company X challenged the CLC's order. The District Court sided with Company X, annulling the remedy order.

- Tokyo High Court: The CLC appealed. The High Court reversed the District Court's decision, thereby upholding the CLC's finding of a ULP and its remedy order.

Company X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed Company X's appeal, affirming the High Court's decision and upholding the CLC's ULP finding. The Court's reasoning was extensive and laid down important principles for employers operating in multi-union environments.

I. General Principles for Employer Conduct in Multi-Union Workplaces

The Court first articulated general principles regarding the employer's duty of neutrality:

- Independent Bargaining Rights: In a workplace with multiple unions, each union, irrespective of its size, possesses the independent right to engage in collective bargaining with the employer over working conditions and to freely decide whether to conclude a collective agreement.

- No Automatic ULP from Different Outcomes: Consequently, if differences in working conditions arise simply because different unions, in a free bargaining environment, make different choices based on their respective policies or assessments, this, in a general and abstract sense, does not constitute an unfair labor practice.

- Prerequisite of Free Union Will: This principle, however, is predicated on the union's decision being genuinely free. The Trade Union Act prohibits employer actions that improperly interfere with a union's organizational strength or solidarity.

- Employer's Duty of Neutrality and Good Faith Bargaining: Employers are obligated to bargain in good faith with all coexisting unions. Moreover, not just in bargaining but in all aspects of labor relations, employers must maintain a neutral attitude towards each union, equally recognizing and respecting their right to organize. Discrimination based on a union's character, tendencies, or past activities is impermissible.

II. Permissible Differentiation Based on Union Strength

The Court acknowledged the realities of bargaining power:

- Where there is a significant disparity in membership size between unions, their respective bargaining power and the impact of their collective actions will naturally differ.

- An employer is permitted to adjust its negotiating stance in response to the actual bargaining power of each union. If a smaller union is unable to achieve its demands due to its weaker bargaining position, this in itself is not a legal issue.

- Specifically, if an employer reaches an agreement with an overwhelmingly large majority union, it is natural for the employer to seek to conclude an agreement with a minority union on similar terms. If the employer then stands firm on these terms with the minority union, this cannot, without more, be deemed an improper negotiating tactic. Even if this leads to an impasse and the minority union's members face economic disadvantages (e.g., by being excluded from benefits tied to the agreement), this is considered a result of the minority union's own choices and strategic judgments.

- An employer's refusal to concede beyond the terms agreed with the majority union, even if it foreseeably leads to economic hardship and potential weakening of the minority union, cannot be automatically presumed to stem from an intent to undermine that union. To hold otherwise would unfairly pressure employers to always concede to minority union demands.

- In essence, while employers have a duty of neutrality and equal treatment, responding in a rational and purposeful manner according to each union's organizational strength and bargaining power does not inherently violate this duty.

III. "Special Circumstances" Indicating ULP Intent

Despite the permissibility of such rational responses, the Court identified a critical exception:

- Even if an employer's stance in collective bargaining appears rational and business-like on its face, if there is a pre-existing act decisively motivated by an intent to deny a particular union's right to organize or by animosity towards that union, and the current collective bargaining is found to be merely a formality to maintain the status quo created by such prior acts, then the employer's actions resulting from these negotiations can constitute an unfair labor practice (domination or interference under TUA Article 7(3)).

- To determine if such "special circumstances" and ULP intent exist, a comprehensive assessment is necessary. This involves examining not just the reasonableness of the bargaining terms themselves, but also:

- The cause and background of how the negotiation item arose.

- The significance of the issue within the overall labor-management relationship.

- The attitudes and actions of both parties concerning the issue after it arose.

- All other relevant factors must be considered to ascertain the presence or absence of ULP intent in the employer's bargaining conduct.

IV. Application to the Nissan Case: Finding ULP Intent

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found that Company X's actions did constitute a ULP:

- Initial Unilateral Action & Disregard for Union Z: Company X introduced the new shift and planned overtime system after consulting only Union B, without any prior discussion or proposal to Union Z. Union Z members were unilaterally placed on day-shifts only and excluded from all overtime from the outset. The Court viewed this as an initial act ignoring Union Z's existence and reflecting an intent to operate the enterprise without its input.

- Insincere Bargaining by Company X: When Union Z later requested overtime, Company X's initial responses were evasive, attributing the lack of overtime to local supervisors' discretion rather than company policy. It was only later, during formal mediated negotiations, that Company X explicitly stated its position that Union Z members must accept the entire work system (including night shifts) to be eligible for planned overtime. This lack of initial transparency and genuine effort to negotiate with Union Z was viewed negatively.

- Historical Animus and Prior ULPs: The Court took into account the historical context, including Company X's (and its predecessor Company A's) unfavorable disposition towards Union Z, especially during the merger when Union Z became a small minority. This history included confirmed ULP findings against the company for conduct such as refusing to bargain with Union Z and improperly aiding the rival union.

- Discrimination in Indirect Departments: The Court found the blanket exclusion of Union Z members from overtime in the indirect departments (office/technical) particularly revealing. In these departments, the operational necessity of the integrated shift/planned overtime system did not apply in the same way as in manufacturing. Company X could have assigned overtime to these Union Z members without issue. The company's justification – lack of trust from supervisors – was deemed insufficient. This broad exclusion strongly suggested an intent to economically pressure Union Z members solely because of their affiliation, thereby aiming to weaken the union.

- Unified Anti-Union Intent: Given that Union Z was a single, unified organization, the Court found it unnatural to assume that Company X's underlying intent regarding overtime differed between the manufacturing and indirect departments. The discriminatory treatment in the indirect sector shed light on the company's overall motivation.

Based on this comprehensive assessment, the Supreme Court concluded that the primary motive and cause for Company X's continued refusal to assign any overtime to Union Z members—despite the appearance of rational bargaining over the integrated work system in manufacturing—was an intent to place Union Z members in a prolonged state of economic disadvantage, thereby creating instability within the union and aiming for its eventual weakening. This constituted a ULP of domination or interference under TUA Article 7(3).

V. The Appropriateness of the Remedy Order

The Court also upheld the CLC's remedy order, which directed Company X not to discriminate against Union Z members in overtime assignments because of their union affiliation. It found this order to be within the Labor Commission's discretionary powers, not overly abstract, and not creating "reverse discrimination." The order's intent was to restore the situation to what it was before the discriminatory exclusion began, after which the company and Union Z could engage in further good-faith negotiations.

Dissenting Opinion:

Justice Hisaharu Kidoguchi dissented, arguing that Company X's actions did not constitute a ULP. He emphasized the operational rationality of the integrated shift and planned overtime system in the manufacturing sector and believed that the lack of overtime for Union Z members stemmed primarily from Union Z's own refusal to accept this system, which the vast majority of employees (via Union B) had accepted.

Analysis and Significance

The Nissan Motor case is a pivotal decision for understanding labor law in workplaces with multiple unions in Japan.

- Elaboration of Employer's Duty of Neutrality: The judgment provides a detailed exposition of the employer's duty to maintain neutrality and provide equal treatment to all coexisting unions. While acknowledging that outcomes of free bargaining may differ, the employer must not use its position or bargaining tactics to undermine a specific union based on anti-union animus. This principle is applicable across all employer-union interactions, not just formal bargaining.

- Bargaining Power vs. Discriminatory Intent: The Court recognized that employers can legitimately respond to the differing bargaining strengths of majority and minority unions. Pressing a minority union to accept terms already agreed with a majority union is not, in itself, a ULP. However, this case clarifies that such a stance becomes illegitimate if it is a pretext for or a continuation of actions motivated by an intent to weaken the minority union.

- "Special Circumstances" and Holistic ULP Assessment: The ruling emphasizes that even if an employer's actions have a veneer of rationality, they can be deemed a ULP if "special circumstances" indicate an underlying anti-union motive that has shaped the current situation. The determination of ULP intent requires a holistic review of all facts, including historical labor relations, the sequence of events, and the conduct of both parties, not merely the surface logic of a bargaining position.

- Evolution of Doctrine: The PDF commentary suggests this case built upon and refined principles from earlier cases like Nihon Mail Order. While Nissan also underscores the importance of the majority union's agreement, it sets out a more comprehensive framework for analyzing the employer's duty of neutrality and the conditions under which differing treatment becomes an unlawful ULP. Some scholars argue that later cases, such as Kochi Broadcasting, further tilted the balance towards recognizing the employer's emphasis on agreements with the majority union.

- Role of Labor Commissions: The nuanced, fact-intensive nature of ULP determinations, especially those involving intent, reinforces the importance of the specialized expertise of Labor Commissions. The PDF commentary alludes to the idea that courts should generally defer to the Commission's discretion in crafting remedies, provided it is not abused.

Conclusion

The Nissan Motor Supreme Court decision provides crucial guidance on navigating labor relations in multi-union environments. It affirms the employer's duty of neutrality but allows for pragmatic responses based on differing union strengths, provided these are not tainted by an intent to undermine any particular union. The judgment's emphasis on a comprehensive, contextual assessment to discern anti-union animus, even behind seemingly rational business decisions, underscores the protective aims of Japan's unfair labor practice system. It remains a vital precedent for both employers and unions in understanding the boundaries of permissible conduct in complex workplace scenarios.