Employer Duty of Care in Japan: Protecting Expatriate Staff During Crises

TL;DR

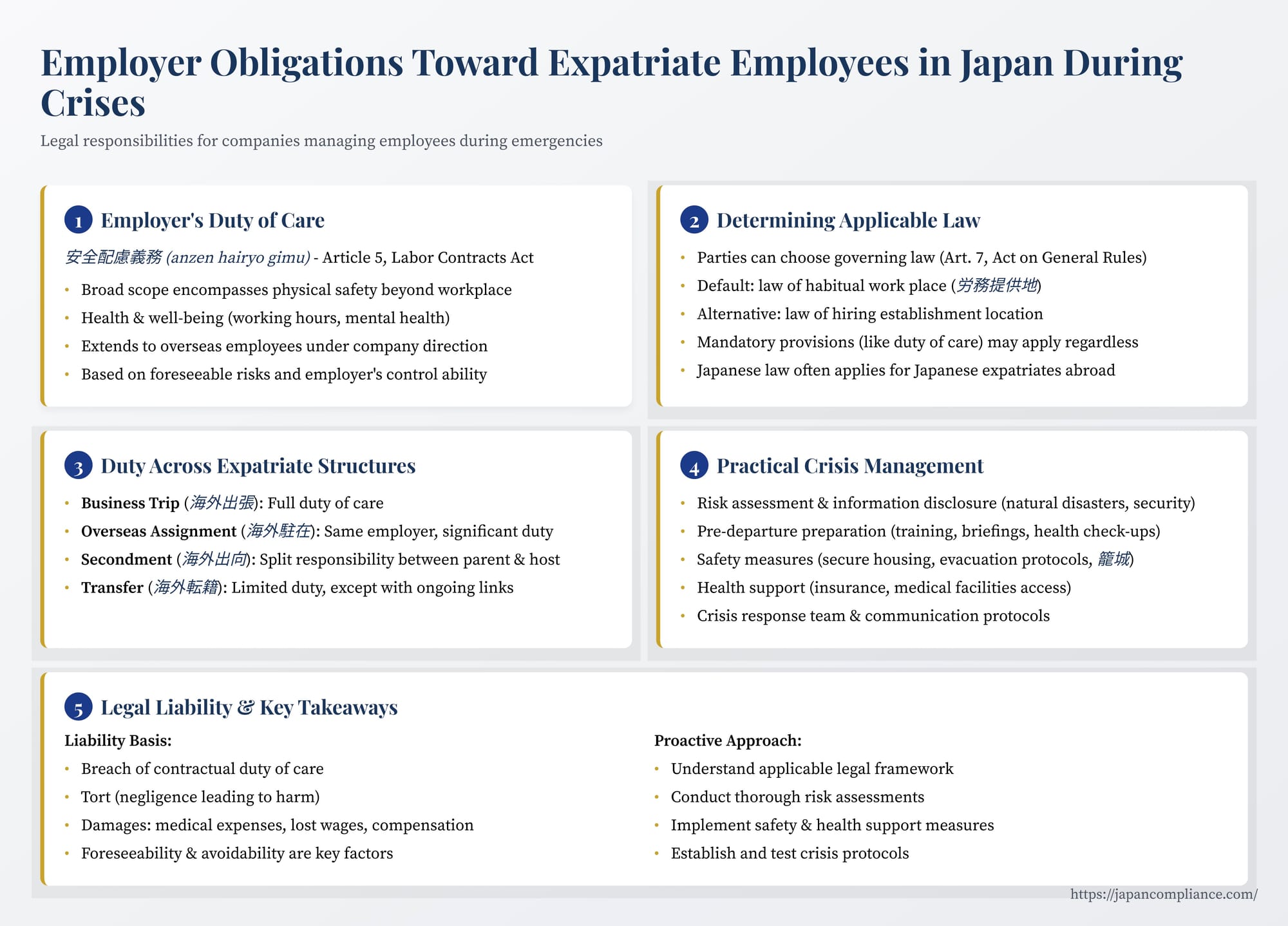

- Japanese “Duty of Care” (Labor Contracts Act Art.5) extends overseas when staff are on trips, postings, or secondments arranged from Japan.

- Even with a foreign governing-law clause, Japanese mandatory protections often still bite.

- Employers must risk-assess destinations, brief staff, secure medical/security support, and maintain real-time crisis protocols—or face breach-of-contract/tort liability.

Table of Contents

- The Core Concept: Employer's Duty of Care (Anzen Hairyō Gimu)

- Determining Which Law Applies (Governing Law)

- Duty of Care Across Different Expatriate Structures

- Fulfilling the Duty of Care in Practice During Crises

- Legal Liability

- Conclusion: Proactive Management is Key

Sending employees on overseas assignments, including to Japan, is a common practice for multinational corporations. While Japan is generally considered a safe country, it is not immune to crises such as natural disasters (earthquakes, typhoons), public health emergencies (like the recent pandemic), or even unforeseen security incidents. When such events occur, companies—particularly the parent or dispatching entity—have legal obligations towards their employees working abroad. Understanding these duties, especially from the perspective of Japanese law which may govern the employment relationship even for expatriates, is crucial for effective risk management and legal compliance.

The Core Concept: Employer's Duty of Care (Anzen Hairyō Gimu)

A central concept in Japanese labor law is the employer's "Duty of Care" (安全配慮義務, anzen hairyō gimu). Explicitly stated in Article 5 of the Labor Contracts Act, this duty requires employers to take necessary consideration to enable their employees to work while ensuring the safety of their life and health. This obligation stems from the principle of good faith inherent in the employment contract.

The scope of this duty is broad and not limited to hazards within the immediate workplace. It encompasses:

- Physical Safety: Protecting employees from physical harm, whether from workplace accidents, environmental hazards, or even third-party actions like crime or terrorism, where foreseeable.

- Health and Well-being: This includes managing working hours to prevent overwork, providing necessary health check-ups, offering support for mental health, and taking steps to prevent harassment.

- Work Environment: Ensuring a generally safe and healthy working environment.

Crucially, this duty extends, to a reasonable degree, to employees working overseas under the company's direction. The specific measures required depend on the foreseeability of the risk and the employer's ability to control or mitigate it.

Determining Which Law Applies (Governing Law)

Before delving into the specifics of the duty of care, it's important to consider which country's law governs the employment relationship of an expatriate employee. Under Japan's Act on General Rules for Application of Laws (法の適用に関する通則法, Hō no Tekiyō ni Kansuru Tsūsokuhō), the parties can generally choose the governing law for their contract (Article 7). However, for employment contracts, there are protective rules. If the parties haven't chosen a governing law, the law of the place where the work is habitually performed (労務提供地, rōmu teikyō chi) is presumed to apply (Article 8(1), Article 12(2)). If that place cannot be determined, the law of the place where the establishment that hired the employee is located (雇入れ事業所地, yatoiire jigyōsho chi) is presumed (Article 12(3)).

Even if a foreign law is chosen by the parties, the employee can still invoke mandatory protective provisions of the law of the place most closely connected with the contract, often the place of habitual work performance (Article 12(1)). Japan's Duty of Care under the Labor Contracts Act is considered such a mandatory provision.

Therefore, even if an expatriate employee working in Japan has a contract stipulating their home country's law, Japanese mandatory provisions like the duty of care might still apply. Conversely, for a Japanese employee sent abroad by a Japanese company, Japanese law (including the duty of care) often continues to apply, especially if they were hired in Japan and expect to return.

Duty of Care Across Different Expatriate Structures

The practical application and extent of the Japanese employer's duty of care can vary depending on the structure of the overseas assignment:

- Overseas Business Trip (海外出張, kaigai shutchō): Employees remain formally attached to their home base in Japan and are temporarily dispatched overseas. The employment contract is clearly governed by Japanese law, and the employer retains full duty of care obligations regarding the employee's safety and health during the trip, considering the risks associated with the destination.

- Overseas Assignment/Posting (海外駐在, kaigai chūzai): The employee is assigned to work at an overseas branch or office of the same Japanese legal entity. While the place of work changes, the employer remains the same. Japanese law often continues to govern the core employment relationship, especially if the employee was hired in Japan and the assignment is for a fixed term with expected repatriation. The employer's duty of care remains significant, requiring proactive safety management concerning the overseas environment.

- Secondment (海外出向, kaigai shukkō): This involves the employee retaining their employment status with the Japanese parent company (dispatching entity) while working under the direction and supervision of a separate legal entity abroad (host entity, often a subsidiary or affiliate).

- Parent Company's Duty: The parent company's duty of care persists under the ongoing employment relationship governed by Japanese law. However, its scope is generally considered secondary to the host entity, which directly manages the employee's daily work and environment. The parent's duty focuses on aspects it can control or influence, such as the selection of the host entity, the terms of the secondment agreement, ensuring the employee receives necessary pre-departure training and information, and responding appropriately if it becomes aware of specific risks (e.g., dangerous working conditions, excessive workload) not being managed by the host entity. Failure to act on known risks could lead to liability.

- Host Entity's Duty: The host entity typically bears the primary responsibility for the day-to-day safety and health of the seconded employee within the workplace abroad, often under local labor laws.

- Transfer (海外転籍, kaigai tenseki): The employee formally resigns from the Japanese company and enters into a new employment contract directly with the foreign entity. In principle, the Japanese company's legal obligations, including the duty of care, cease upon termination of the original employment relationship. However, complexities can arise if the transfer is part of a group strategy with strong ongoing links, expected repatriation, or if the parent company continues to exercise significant de facto control over the employee's conditions. In such cases, arguing for a complete absence of responsibility might be difficult, although the legal basis would shift away from the direct employment contract duty.

Fulfilling the Duty of Care in Practice During Crises

The duty of care is not merely theoretical; it requires employers to take concrete, reasonable steps to protect their employees, particularly during crises. The standard is generally one of reasonableness – what measures are feasible and appropriate given the foreseeable risks?

Key Areas of Consideration:

- Risk Assessment and Information Disclosure: Before and during an assignment, employers have a duty to gather information about potential risks in the host country/region – including natural disaster frequency (earthquakes, typhoons in Japan), political stability, crime rates, prevalent diseases, terrorism threats, and public health infrastructure capacity. Reliable sources include government travel advisories (like those from Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs - MOFA), security consulting firms, and local contacts. This information must be communicated clearly to the employee, along with relevant safety advice and training. Ignoring foreseeable risks can be grounds for liability.

- Pre-Departure Preparation: Providing adequate preparation, including cross-cultural training, security briefings tailored to the local environment, health check-ups, necessary vaccinations, and information on accessing medical care abroad, is essential.

- Safety and Security Measures: Depending on the assessed risk level, measures may include:

- Providing guidance on selecting safe housing (e.g., earthquake-resistant buildings, secure access).

- Establishing robust emergency communication plans (multiple channels, regular check-ins).

- Developing clear protocols for lockdowns ("shelter-in-place" or 籠城 rōjō), evacuation, or temporary relocation, including identifying safe havens and transportation options.

- Arranging security support (e.g., secure transport, coordination with local security providers) in high-risk environments. MOFA and industry associations sometimes provide resources or networks for companies, especially SMEs, to enhance security preparedness.

- Health and Medical Support: Ensuring employees have adequate health insurance coverage for the host country, access to reliable medical facilities (including mental health support), and clear procedures for handling medical emergencies or illness outbreaks (like pandemics) is critical. This includes facilitating necessary treatments and, if required, medical evacuation.

- Crisis Response Management: Having a dedicated crisis management team and clear protocols is vital. This includes:

- Monitoring the situation continuously.

- Maintaining regular contact with employees.

- Making timely decisions regarding employee safety (e.g., work-from-home mandates, temporary relocation, evacuation authorization).

- Providing logistical and financial support for employees and their families affected by the crisis.

- Coordinating with local authorities and embassies/consulates.

Foreseeability and Avoidability: Liability for breach of the duty of care generally arises when the employer fails to take reasonable measures against foreseeable risks, resulting in avoidable harm. What is "foreseeable" and "avoidable" depends heavily on the specific circumstances, the nature of the crisis, the location, and the resources reasonably available to the employer. A sudden, unpredictable natural disaster might entail different expectations than operating in a known conflict zone or during a declared pandemic. Case law often examines whether the employer gathered appropriate information and implemented measures considered standard or reasonable for the known risks. For instance, a Tokyo High Court decision on January 25, 2023, while dealing with a domestic company employee's accident during an overseas business trip (to Malaysia), discussed the scope of the employer's duty of care concerning arrangements made for local transportation, implicitly acknowledging the duty extends beyond Japan's borders.

Legal Liability

Failure to adequately fulfill the duty of care can lead to legal liability for the employer if an employee suffers harm (physical injury, illness, psychological damage, or death) as a result. Claims can typically be brought as:

- Breach of Contract: Violating the duty of care implied in the employment contract.

- Tort: Negligence leading to harm.

Damages may include medical expenses, lost wages, compensation for pain and suffering, and potentially damages for dependents in fatal cases.

Conclusion: Proactive Management is Key

Ensuring the safety and well-being of expatriate employees, especially during crises, is not just a moral imperative but also a significant legal obligation under Japanese law, particularly for Japanese companies dispatching employees or foreign companies whose Japanese operations employ expats under conditions where Japanese law might apply. The duty of care (anzen hairyō gimu) requires a proactive, risk-based approach.

Companies must:

- Understand which legal framework (Japanese law, home country law, local law) governs the specific employment relationship.

- Recognize that the Japanese duty of care likely applies in many expatriate scenarios involving Japanese entities or assignments originating from Japan.

- Conduct thorough risk assessments for assignment locations.

- Provide comprehensive pre-departure training and ongoing information updates.

- Implement practical safety, security, and health support measures tailored to the environment and the nature of the work.

- Establish and regularly test robust crisis management and communication protocols.

- Clearly define responsibilities, especially in secondment arrangements involving parent and host entities.

By taking these steps, companies can better protect their employees abroad and mitigate the significant legal and reputational risks associated with failing to meet their duty of care obligations during challenging times.

- Navigating Japan’s Legal Landscape During Public-Health Crises: Lessons from the Pandemic

- Post-Pandemic Japanese Labor Law: Dismissal, Relocation & Side-Job Pitfalls Explained

- A Step Towards Inclusion: Japan’s Supreme Court Rules on Transgender Employee Restroom Access

- MOFA Overseas Safety Information Portal (Japanese)

- Cabinet Secretariat – Infectious-Disease Crisis Management Agency Overview