Employer Liability for Overwork Suicide (Karō Jisatsu): Japan's Landmark Ruling (March 24, 2000)

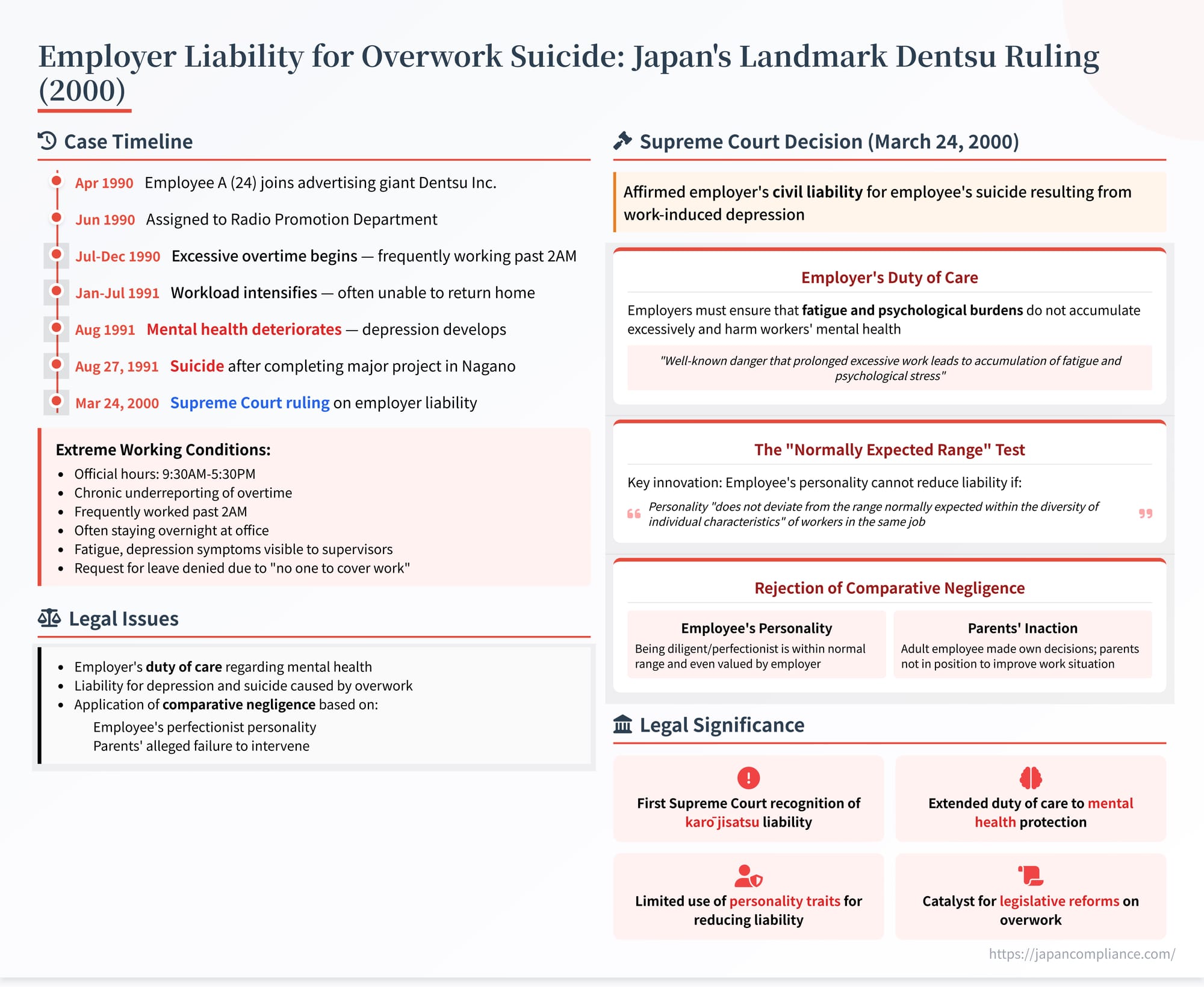

Japan’s Supreme Court held Dentsu liable for an employee’s overwork suicide, expanding employer duty of care to mental health and limiting comparative negligence.

TL;DR

- Landmark decision (Supreme Court, 24 Mar 2000) held Dentsu liable for a junior employee’s suicide caused by chronic overwork.

- Employer duty: extends to preventing mental‑health harm from excessive workload.

- Comparative negligence limited: normal‑range personality traits and family inaction cannot cut damages.

- Legacy: key precedent in Japan’s fight against karōshi / karō jisatsu; basis for later legislation and compliance practices.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: A Young Life Consumed by Overwork

- Legal Proceedings: Liability and the Question of Shared Fault

- Legal Framework: Employer's Duty and Comparative Negligence

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (March 24 2000): Affirming Liability, Rejecting Negligence Reduction

- Remand for Recalculation

- Implications and Significance: The Dentsu Precedent

- Conclusion

On March 24, 2000, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment that profoundly impacted labor law and corporate responsibility in Japan (Case Nos. 1998 (O) No. 217 & 218, "Damages Claim Case" ). The case involved the tragic suicide of a young employee of the advertising giant, which his parents attributed to depression brought on by extreme and chronic overwork. The Supreme Court upheld the finding of employer liability, affirming the employer's duty of care extends to preventing mental health issues caused by excessive workload. Crucially, the Court also placed significant limitations on the extent to which an employee's personality or family circumstances could be used to reduce the employer's damages under the doctrine of comparative negligence. This decision marked a pivotal moment in the legal recognition of karō jisatsu (suicide due to overwork) and strengthened employer obligations regarding employee well-being in demanding work environments.

Factual Background: A Young Life Consumed by Overwork

The case painted a harrowing picture of a young employee's descent into despair under intense work pressure:

- The Employee: A (born November 1966) was described as healthy, athletic, bright, cheerful, honest, responsible, persistent, and tending towards perfectionism. He joined the prominent advertising agency Y in April 1990, after graduating from Meiji Gakuin University.

- Assignment and Initial Work: After training, A was assigned to the Radio Promotion Department in June 1990, working under Section Chief S within Manager T's department. His main tasks involved soliciting corporate clients to sponsor radio programs and planning/executing promotional events for clients. His typical workday involved external meetings and contacts during the day, followed by internal tasks like preparing proposals and materials often starting only after 7 PM. Despite the demanding nature, A was initially enthusiastic and well-regarded by superiors and colleagues.

- Escalating Overwork: From the outset, A's work hours became extremely long.

- Working Hours & Conditions at Y: Y had official working hours (9:30 AM - 5:30 PM) and collective agreements (三六協定 - saburoku kyōtei) setting limits on overtime (e.g., 6.5 hours/day, 60 or 80 hours/month depending on the period). However, chronic long overtime was common practice at Y, with many employees exceeding agreement limits. Furthermore, underreporting of actual overtime hours by employees was "normalized" (jōtaika shite ita). Y management was aware of these issues, including the problem of work being concentrated on specific individuals. While some measures existed (like company-paid hotel rooms for employees finishing after midnight), they were not well-utilized, especially by new employees like A.

- A's Specific Workload (July 1990 - Aug 1991): A's reported overtime hours (recorded monthly from 48 to 87 hours) were significantly less than his actual hours worked. Critically, the court record included data on how often A left the office after 2:00 AM, indicating frequent all-nighters or near all-nighters (details were in an appendix to the original judgment). While he took short breaks for meals or naps, the vast majority of his time at the office was spent working.

- Progression of Exhaustion: From around August 1990, A frequently returned home very late (1-2 AM). By late November 1990, he began staying overnight at the office or his father's nearby office. His parents (X, the appellants, with whom he lived) grew increasingly concerned about his health. His father urged him to take paid leave, but A responded that there was no one to cover his work, he would suffer later if he took time off, and his superiors had questioned his workload capacity when he previously mentioned wanting leave. In January 1991, A began handling about 70% of his work independently. While his performance reviews were generally positive (noting his diligence and responsiveness), the workload did not decrease.

- Deterioration (July-August 1991): A's workload increased further from July 1991 when he became solely responsible for certain accounts. He was frequently unable to return home at all, or would return very early in the morning (6:30-7:00 AM) only to leave again by 8:00 AM. His parents observed severe fatigue and tried to support him (nutritious meals, driving him to the station). A appeared drained, depressed ("gloomy," "despondent" - genki ga naku, kurai kanji de,utsu utsu to shi), pale, and sometimes unfocused. His direct supervisor, S, noticed his deteriorating health. In August 1991, A told S things like "I have no confidence," "I don't know what I'm saying," and "I can't sleep."

- The Final Project and Suicide: From August 1-23, 1991, A worked almost every day, including weekends, except for a short trip (for which he took his first paid leave day of the fiscal year). From August 24-26, he managed a client event in Nagano prefecture, staying at S's villa. S noticed abnormal behavior from A during this time. A returned home around 6:00 AM on August 27. He told his younger brother he needed to go to the hospital. He called work around 9:00 AM saying he was unwell and taking the day off. Around 10:00 AM, he was found dead, having taken his own life in the family bathroom.

- Medical Context: The Court considered medical knowledge regarding depression (utsubyō) and suicide: depression is an affective disorder often triggered by chronic fatigue, sleep deprivation, and stress; individuals with depression have a higher risk of suicide, particularly during phases of worsening or initial improvement, or sometimes impulsively after achieving a major goal (when the immediate pressure lifts but perspective remains bleak). Certain personality traits (diligent, responsible, perfectionist – sometimes termed shūchaku kishitsu) can increase susceptibility.

- Causation Finding: The lower courts found (and the Supreme Court affirmed) that A's constant and excessive workload led him to a state of severe mental and physical exhaustion by July 1991. This triggered clinical depression by early August 1991. The completion of the Nagano event likely led to a worsening of his depressive state, resulting in his impulsive suicide on August 27.

Legal Proceedings: Liability and the Question of Shared Fault

A's parents (X) sued Y for damages, alleging that A's death resulted from the negligence of his superiors (breach of duty of care) in failing to manage his workload and protect his health, leading to his depression and suicide. They claimed damages under Civil Code Article 715 (employer liability for torts of employees).

The High Court (Tokyo High Court) found Y liable. It determined that A's superiors were aware of his extreme, prolonged overwork and deteriorating health, yet failed to take appropriate measures to reduce his burden. It found a causal link between this negligence, A's depression, and his suicide. However, the High Court reduced the damages award by 30%, applying the principle of comparative negligence (kashitsu sōsai). It attributed this 30% reduction to two factors:

- A's Personality: His perfectionist and highly responsible nature was deemed a "psychological factor" contributing to the harm.

- Parents' Inaction: The court found the parents, despite knowing A's situation, failed to take "concrete measures" to improve it, considering this a contributing factor.

Both Y (disputing liability) and X (disputing the negligence reduction) appealed to the Supreme Court.

Legal Framework: Employer's Duty and Comparative Negligence

The case involved several key legal concepts:

- Employer's Duty of Care (安全配慮義務 - Anzen Hairyo Gimu): While not explicitly codified in the Labour Contract Act until later (Art. 5), Japanese courts had long recognized an employer's implied contractual or tort-based duty, derived from principles of good faith or safety regulations (like LSA and the Labour Safety and Health Act - LSHA), to take reasonable steps to protect employees' life and health from risks associated with their work. This case tested the extent to which this duty applied to mental health risks arising from overwork.

- Employer Liability (民法715条 - Minpō 715-jō): Makes an employer liable for damages caused by an employee's tort committed in the course of employment, provided the employer failed in appointing or supervising the employee (though this fault is often presumed or based on the supervisor's own negligence).

- Causation (相当因果関係 - Sōtō Inga Kankei): The legal requirement to show a proximate causal link between the employer's breach of duty (negligence) and the resulting harm (employee's depression and suicide).

- Comparative Negligence (過失相殺 - Kashitsu Sōsai, 民法722条2項 - Minpō 722-jō 2-kō): Allows a court to reduce the defendant's damages liability if the plaintiff's own negligence contributed to the occurrence or extent of the damage. Courts sometimes apply this doctrine by analogy (ruisui tekiyō) to account for victim-side factors beyond explicit negligence, such as pre-existing vulnerabilities or certain personality traits ("psychological factors" - shin'in teki yōin).

The Supreme Court's Analysis (March 24, 2000): Affirming Liability, Rejecting Negligence Reduction

The Supreme Court delivered a powerful judgment, affirming Y's liability but decisively rejecting the High Court's reduction of damages based on comparative negligence.

1. Affirming Employer's Duty Regarding Mental Health from Overwork:

- The Court explicitly recognized the employer's duty of care extends to preventing harm to employees' mental health caused by excessive workload.

- Rationale: It cited the "well-known" (shūchi) danger that prolonged excessive work leads to accumulation of fatigue and psychological stress, risking harm to workers' "mental and physical health" (shinshin no kenkō o sokonau). It referenced LSA working hour limits and LSHA's general duty for employers to appropriately manage work considering worker health (LSHA Art. 65-3) as legal underpinnings for this duty.

- Duty Defined: "Employers... have a duty (gimu o ou) to exercise care (chūi suru) to ensure that fatigue and psychological burdens (hirō ya shinriteki fuka tō) accompanying the performance of duties do not accumulate excessively (kado ni chikuseki shite) and harm the mental and physical health of their workers."

- Supervisors' Responsibility: This duty also binds those with authority to direct and supervise workers (superiors must exercise their authority consistent with this duty).

- Breach and Causation Affirmed: The Court upheld the High Court's findings that A's superiors (T and S) breached this duty by failing to take workload reduction measures despite knowing A's extreme hours and deteriorating health, and that this breach was causally linked to A's depression and suicide. Y's appeal challenging liability was dismissed.

2. Rejecting Comparative Negligence Based on Personality:

This was a crucial part of the ruling, setting a new standard.

- General Principle Acknowledged: The Court acknowledged the possibility, established in a 1988 precedent, of considering a victim's "psychological factors such as personality" under comparative negligence principles to achieve a fair allocation of loss.

- New Limitation: The "Normally Expected Range" Test: However, the Court introduced a significant limitation specifically for cases involving harm caused by excessive workload:

- Personality within the normal range cannot be used for offset. The Court reasoned that employers hire people with diverse personalities, and a certain range of traits is expected. If a particular employee's personality "does not deviate from the range normally expected within the diversity of individual characteristics of workers engaged in the same type of work" (dōshu no gyōmu ni jūji suru rōdōsha no kosei no tayōsa to shite tsūjō sōtei sareru han'i o hazureru mono de nai kagiri), then the employer should anticipate how work pressures might affect such an individual.

- Employer's Role in Assignment: Furthermore, employers consider personality when assigning roles and managing employees.

- Conclusion: Therefore, if an employee with a "normal range" personality suffers harm due to excessive work burden (which the employer failed to manage), "their personality and resulting work style... cannot be taken into account as psychological factors" (sono seikaku oyobi kore ni motozuku gyōmu suikō no taiyō tō o, shin'in teki yōin to shite shinshaku suru koto wa dekinai) to reduce the employer's damages.

- Application to A: A's personality (diligent, responsible, perfectionist) was deemed common and even valued by his superiors for the job. It did not fall outside the normally expected range. Thus, the High Court erred in reducing damages based on A's personality.

3. Rejecting Comparative Negligence Based on Parents' Inaction:

The Court also firmly rejected the High Court's consideration of the parents' (X's) alleged failure to act.

- A's Independence: A was an independent adult, employed and making his own decisions regarding his work.

- Parents' Lack of Control: While they lived together and were deeply concerned, the parents "were not in a position to be able to take measures to improve A's work situation" (kinmu jōkyō o kaizen suru sochi o toriuru tachiba ni atta to wa, yōi ni iu koto wa dekinai). Attributing fault to them for the outcome was legally incorrect.

Conclusion on Comparative Negligence: The High Court's 30% reduction based on these factors was found to be an error in legal interpretation and application.

Remand for Recalculation

Because the High Court had improperly reduced the damages based on comparative negligence, the Supreme Court vacated that part of the High Court's judgment (the part unfavorable to the parents X) and remanded the case back to the Tokyo High Court. The purpose of the remand was solely to recalculate the final damages award without applying the erroneous 30% reduction.

Implications and Significance: The Precedent

The 2000 ruling remains one of the most important Supreme Court decisions in Japanese labor law, with far-reaching consequences:

- Landmark Recognition of Karō Jisatsu Liability: It provided the first clear and definitive Supreme Court endorsement of employer civil liability for employee suicide linked to depression caused by overwork. It sent a powerful message about corporate responsibility for preventing such tragedies.

- Broadened Employer Duty of Care: It firmly established that the employer's duty to ensure a safe workplace extends beyond physical hazards to encompass mental health risks arising from excessive workload and stress. Employers must actively manage workloads to prevent harmful levels of fatigue and psychological burden.

- Significant Limitation on Using Personality for Negligence: The "normally expected range" test drastically limited the ability of employers to argue that an employee's pre-existing personality (e.g., being "too serious" or "perfectionistic") contributed to their mental breakdown or suicide, thereby reducing liability. This protects employees from being penalized for common personality traits.

- Reduced Scope for Blaming Families: The ruling made it much harder to attribute fault to family members for not preventing a work-related mental health crisis or suicide, keeping the focus on the employer's workplace responsibilities.

- Catalyst for Change: The decision significantly raised public and corporate awareness of karōshi and karō jisatsu. It contributed to legislative changes (e.g., strengthening health measures for employees working long hours) and influenced administrative standards for recognizing mental disorders and suicides as work-related under the WCAI Act. It remains a cornerstone case referenced in subsequent litigation and policy discussions regarding workplace mental health and overwork prevention.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 24, 2000, judgment in the case was a watershed moment in Japanese labor law. It unequivocally affirmed an employer's duty of care to protect employees' mental health from the dangers of excessive workload and established civil liability for suicides resulting from work-induced depression. Furthermore, by severely restricting the use of an employee's "normal range" personality or family inaction as grounds for reducing damages via comparative negligence, the Court strengthened protections for employees in high-pressure work environments and placed a clear onus on employers to proactively manage workloads and prevent the devastating consequences of overwork.

- Workers' Comp vs. Consolation Money: Japan’s Supreme Court Separates Financial and Non‑Financial Damages

- What Types of Damages Can Be Claimed and How Are They Calculated in Japanese Torts?

- Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

- Realizing a Society in Which No One Is Driven to Suicide – MHLW

- Understanding and Utilizing Labor Laws (Pamphlet) – MHLW

- 13th Occupational Safety & Health Program – MHLW