Employee Stock Ownership Plans and Share Repurchase Obligations: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Judgment Date: April 25, 1995

Case: Action for Issuance of Share Certificates (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

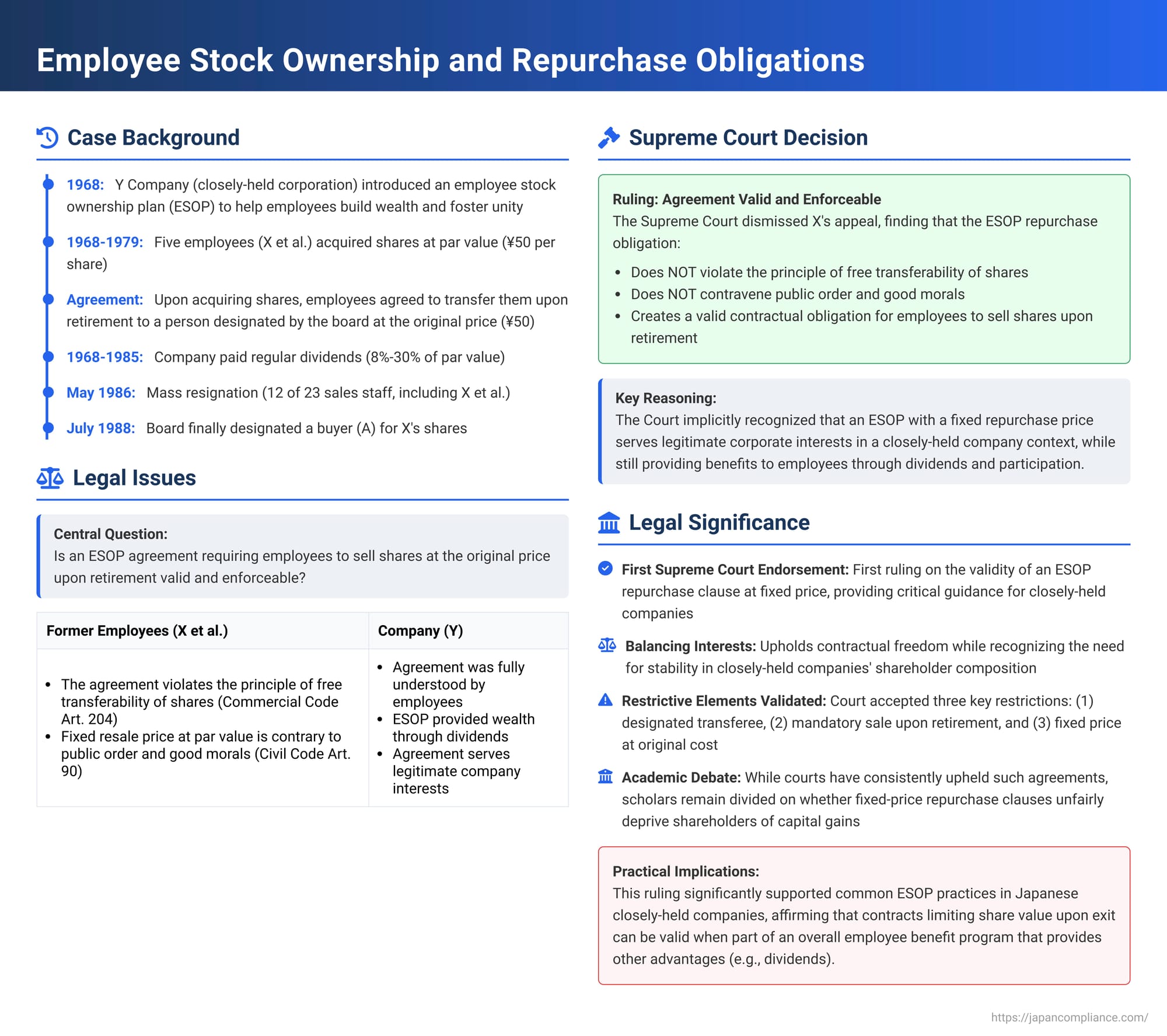

This Japanese Supreme Court decision from 1995 addresses the validity of common provisions in employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), particularly in closely-held companies. The central issue was whether an agreement compelling retiring employees to sell their company shares—acquired under an ESOP—back to a party designated by the company, at the original acquisition price (par value), is enforceable. The challenge to such an agreement was mounted on grounds that it violated the principle of free transferability of shares and general public policy.

Factual Background: An ESOP, Mass Resignation, and a Repurchase Clause

The case involved Y Company, a closely-held, family-type corporation with share transfer restrictions stipulated in its articles of incorporation.

- ESOP Introduction: Around 1968, Y Company implemented an ESOP. The stated goals were to assist employees in building personal wealth and to foster a stronger sense of unity between the employees and the company, thereby contributing to the company's growth and development.

- Share Acquisition and Agreement: Between 1968 and 1979, X et al. (the five appellants), who were all employees of Y Company, acquired shares in the company under this ESOP. They did so with a full understanding of the plan's purpose and terms, purchasing the shares at their par value of JPY 50 per share. Crucially, upon acquiring these shares, each of them entered into an agreement with Y Company (the "Agreement"). This Agreement stipulated that "upon retirement, they would transfer the shares acquired under the ESOP to a person designated by the board of directors at a price of JPY 50 per share."

- Mass Resignation and Delayed Share Repurchase: Y Company had approximately 40 employees. In May 1986, a significant number of employees—12 out of the 23 sales staff, a group that included X et al.—resigned from the company. Due to the ensuing disruption and confusion caused by this mass resignation, Y Company's board of directors did not immediately designate a purchaser for the shares held by X et al. It was not until July 1988 that the board designated A (the child of Y Company's representative director) as the transferee. A subsequently expressed their intention to purchase the shares and deposited the corresponding purchase price.

- Dividend History: Y Company had a history of paying dividends. From fiscal year 1968 onwards, dividends were initially around 15% to 30% of the shares' par value. From fiscal year 1981 to 1985, the dividend rate was 8%. However, no dividend was paid in fiscal year 1986, a fact attributed to the severe negative impact the mass resignations had on the company's business operations.

- Legal Challenge by Former Employees: X et al. initiated legal proceedings against Y Company, demanding that the company issue share certificates for the shares they held. Their core argument was that the Agreement compelling them to resell their shares at par value was void. They contended it violated the principle of free transferability of shares (enshrined in the then-Commercial Code Article 204(1), which corresponds to Article 127 of the current Company Law) and was contrary to public order and good morals (as per Article 90 of the Civil Code).

- Lower Court Decisions: Both the court of first instance and the High Court dismissed the claims made by X et al. The High Court reasoned that:

- The principle of free transferability of shares (then Commercial Code Art. 204(1)) did not directly govern the validity of individual contracts entered into between a company and its shareholders.

- Concerning the public policy argument (Civil Code Art. 90), the ESOP did provide employees with a means for wealth creation through dividends to a reasonable extent. The court found that the fixed resale price of JPY 50 per share did not automatically render the Agreement an unreasonable restriction on the recovery of invested capital, especially considering the overall context of the ESOP.

X et al. subsequently appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Agreement Upheld

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, affirming the judgment of the High Court.

The Court's concise reasoning was that the Agreement—which required employees, upon retirement, to sell shares acquired under the ESOP back to a person designated by the board of directors at the original par value—was not in violation of the then-Commercial Code Article 204(1) (regarding free transferability of shares) and did not contravene public order and good morals (Civil Code Article 90). Therefore, the Agreement was deemed valid.

As a consequence of this valid Agreement, when Y Company's board designated A as the transferee, and A expressed a clear intention to purchase the shares (and deposited the funds), X et al. were considered to have lost their status as shareholders. Accordingly, their demand for the issuance of share certificates was correctly rejected by the lower courts.

Analysis and Implications: ESOPs in Closely-Held Companies

This 1995 Supreme Court decision was significant as it was the first time the highest court in Japan had ruled on the validity of such repurchase clauses at a fixed acquisition price within the framework of an ESOP in a closely-held company.

1. Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) in Japan:

ESOPs are widely used in Japan for various purposes, including fostering employee wealth, enhancing motivation and a sense of participation in management, and creating a stable shareholder base. While approximately 90% of listed companies in Japan have ESOPs, often managed formally by securities firms or trust banks, these plans are also utilized by unlisted, closely-held companies. In the latter, ESOPs can vary greatly in form and often lack the standardized structure seen in listed companies, which can lead to disputes.

2. Judicial History (Lower Courts):

Prior to this Supreme Court ruling, lower courts had almost consistently upheld the validity of such agreements requiring repurchase at or near acquisition cost upon an employee's retirement. There was only one reported instance of a lower court deeming such a contract invalid. These cases often involved the company itself as a party to the agreement, and courts typically considered the ESOP's objectives, its specific terms, and the company's dividend payment history in their assessments. Early judgments tended to analyze the agreements in relation to share transferability principles, while later ones, possibly influenced by evolving academic discourse, focused more on whether the agreements violated public policy under Civil Code Article 90. The Supreme Court in this 1995 case addressed both legal challenges. The general approach of this judgment was also maintained in a subsequent Supreme Court decision on February 17, 2009.

3. Academic Perspectives on Share Transfer Restriction Agreements:

The legal validity of contractual restrictions on share transfers has been a subject of considerable academic debate:

- Traditional Majority View: This view distinguishes the validity criteria based on whether the company itself is a party to the restrictive agreement.

- Company-Shareholder Agreements: Generally viewed as presumptively void because they could easily be used to circumvent the statutory principle of free share transferability (Company Law Art. 127). However, they might be deemed exceptionally valid if their terms are reasonable and do not unfairly prevent shareholders from recovering their invested capital.

- Shareholder-Shareholder or Shareholder-Third Party Agreements: These are generally considered valid as they fall outside the direct scope of Company Law Art. 127. They would only be invalidated exceptionally if found to be a means of circumventing rules applicable to company-shareholder agreements.

- Freedom of Contract View: A strong counter-argument posits that the principle of freedom of contract should also apply to agreements where the company is a party. Such agreements would only be void if they violate public order and good morals under Civil Code Article 90. This is sometimes referred to as an issue of "corporate law public policy."

- "Underlying Ideal" View: Another noteworthy perspective suggests that while Company Law directly regulates charter-based restrictions, its provisions reveal an underlying principle that any form of share transfer restriction (including contractual ones) must not unreasonably deprive shareholders of the opportunity to recoup their invested capital. Contracts that contradict this ideal are considered void.

4. Analyzing the Specific Agreement in this Case (Commentary):

The PDF commentary accompanying the case highlights three restrictive elements in the Agreement between Y Company and X et al.:

1. The transferee was limited to a person designated by the company's board of directors.

2. A mandatory obligation to sell the shares was triggered by a future event (retirement), effectively removing the freedom not to sell at that point.

3. The future transfer price was fixed in advance at the original acquisition cost.

The commentator offers the following analysis:

- Designated Transferee: Restricting the choice of transferee is generally acceptable, as Company Law itself often subordinates a shareholder's freedom to choose a buyer to the company's interest in maintaining a closed circle of shareholders (e.g., Company Law Art. 140(1), (4)). However, if the period for the company to designate a buyer is unreasonably long (the commentator suggests over 40 days as a benchmark, drawing an analogy from Company Law Art. 145(2)), the agreement might become an undue restriction on the timing of the transfer and thus be void. In the present case, no specific timeframe was set for designation, implying it should occur within a "reasonable time." The commentator questions whether Y Company's delay of over two years in designating A was reasonable, suggesting Y Company's right to designate might have lapsed.

- Mandatory Sale Upon Event: Agreements that impose a sale obligation upon certain events like retirement or death are generally considered compatible with the principle of free share transferability. Such clauses can actually facilitate capital recovery for shareholders, especially in closely-held companies where finding a buyer might otherwise be difficult.

- Fixed Price at Par Value: While agreeing in advance on a reasonable method for calculating the share price at the time of future transfer is generally acceptable and practically useful (even if the resulting price is below market value), fixing the future sale price at the original acquisition price (par value) completely negates any opportunity for capital gains. The commentator argues that this cannot be considered a genuine recovery of invested capital unless there are exceptional circumstances, such as a near 100% dividend payout ratio. The rationality of such a price-fixing method is therefore questionable.

5. Broader Considerations from Commentary:

The provided commentary suggests that while the Company Law provides a framework for balancing transfer restrictions (often needed by companies) and capital recovery (needed by shareholders) through charter-based mechanisms, contractual restrictions offer more flexibility. Because contractual restrictions only bind the parties involved, require actual consent (unlike uniformly imposed charter provisions), and serve important practical functions, they might be allowed to deviate from the strict balance set for charter-based restrictions, provided such deviations are within reasonable limits. When a party other than the company imposes restrictions, freedom of contract generally prevails, unless that party is effectively an alter ego of the company.

Conclusion: Judicial Support for ESOP Repurchase Clauses

The Supreme Court's 1995 decision provided significant legal backing for a common feature of ESOPs in Japanese closely-held companies: the obligation for retiring employees to resell their shares at a predetermined, often nominal, price. The Court found such an agreement to be valid, not infringing upon the principle of free share transferability or public policy, given the context of an ESOP designed for employee benefit and company cohesion. While the judgment offers practical support for such plans, academic commentary continues to scrutinize certain aspects, particularly the fairness of fixed low resale prices that preclude capital gains, highlighting an ongoing tension between the practical needs of closely-held companies and broader shareholder protection principles.