Employee Rights in Company Splits: Japanese Supreme Court on the Duty to Consult and Labor Contract Succession

Judgment Date: July 12, 2010

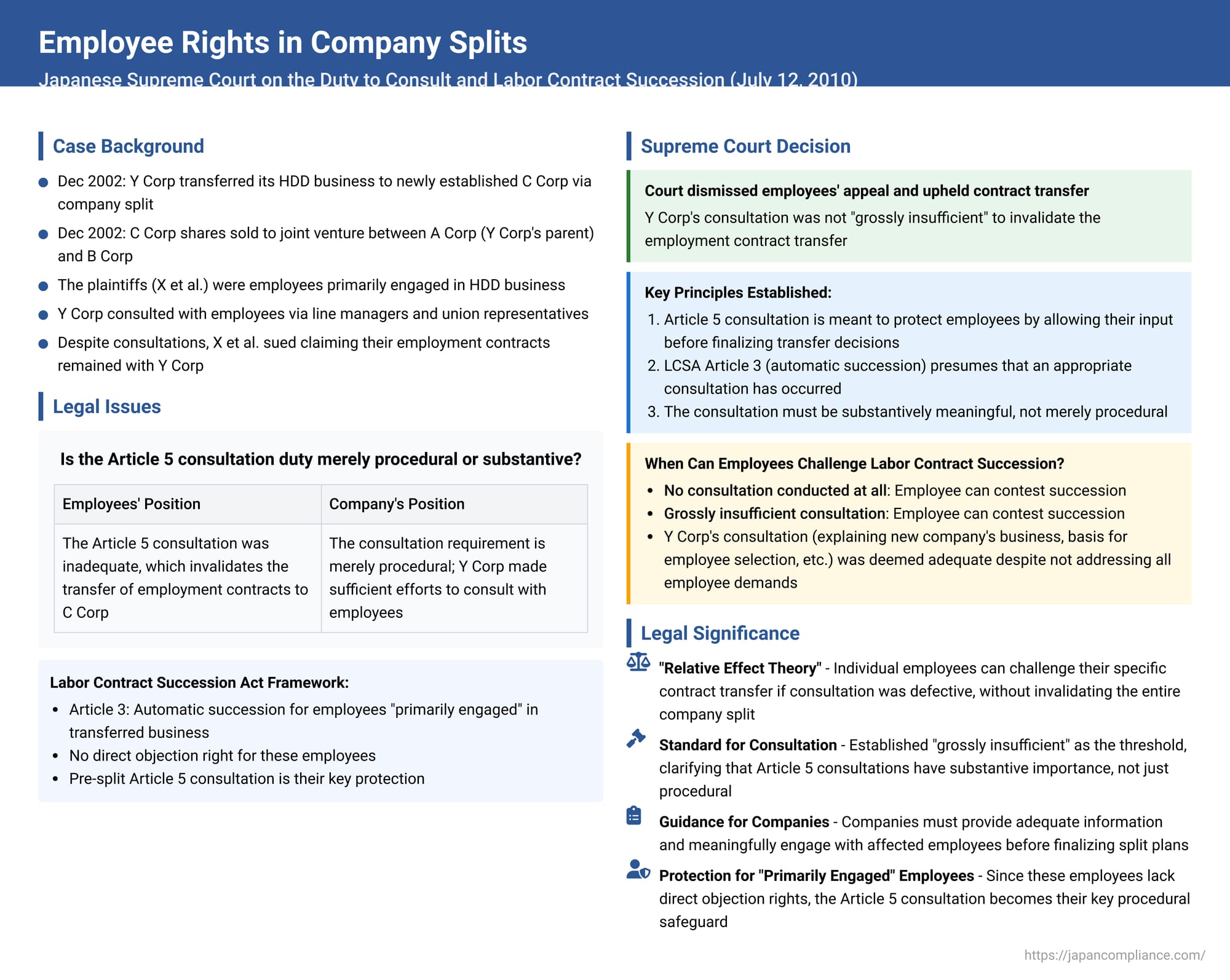

Company splits (会社分割 - kaisha bunkatsu), a form of corporate demerger or division, are a significant tool for business restructuring in Japan. When a company splits, the fate of its employees' employment contracts is a critical concern. Unlike mergers where employment contracts generally transfer comprehensively, or business transfers (asset sales) where individual employee consent is typically required for their contracts to move, company splits operate under a special legal framework in Japan, primarily governed by the Labor Contract Succession Act (LCSA) and specific provisions related to the company split process itself. A key element of this framework is the employer's duty to consult with affected employees prior to the split. A 2010 Supreme Court of Japan decision provided crucial clarification on the nature of this consultation duty and the consequences if it is not properly fulfilled, particularly for employees whose contracts are designated for transfer to the new entity.

The Corporate Restructuring and Employee Concerns

The case involved Y Corp, a wholly-owned Japanese subsidiary of a U.S. corporation, A Corp. The dispute arose from a major restructuring of Y Corp's Hard Disk Drive (HDD) business:

- Joint Venture Plan: Around April 2002, Y Corp's parent, A Corp, entered into an agreement with another company, B Corp, to establish a joint venture (JV) focused on the HDD business. The plan was to consolidate their respective global HDD operations under this JV, with an eventual goal of the JV becoming a wholly-owned subsidiary of B Corp.

- Incorporation-Type Company Split: As part of this broader strategy, Y Corp was to transfer its HDD business to a newly created, wholly-owned subsidiary. On December 25, 2002, Y Corp effected this through an "incorporation-type company split" (shinsetsu bunkatsu), establishing C Corp and transferring the HDD business to it.

- Transfer to JV and Subsequent Integration: On December 31, 2002, all shares of the newly formed C Corp were sold to the A Corp/B Corp joint venture company. On January 1, 2003, C Corp's name was changed to reflect its new affiliation, incorporating part of B Corp's name. Later, on April 1, 2003, B Corp's own HDD business was transferred to C Corp via an absorption-type company split, further consolidating operations within C Corp. By June 1, 2005, common work rules were implemented for all employees in C Corp, whether they originated from Y Corp or B Corp.

The plaintiffs, X et al., were employees of Y Corp who were primarily engaged in its HDD business. As a result of the incorporation-type company split, their employment contracts were designated to be transferred from Y Corp to the new entity, C Corp.

The "Article 5 Consultation" Process

Before the company split took effect, Y Corp engaged in a legally mandated consultation process with its employees. This referred to the "Article 5 consultation" (5条協議 - go-jō kyōgi) stipulated under Article 5, Paragraph 1 of the Supplementary Provisions of the Act Amending the Commercial Code, etc. (the law that introduced company splits into the Commercial Code, which was the predecessor to the current Companies Act). This provision required the splitting company to consult with its employees regarding the succession of their labor contracts before finalizing and formally lodging the split plan.

Y Corp's consultation efforts included:

- Having line managers in the HDD division explain the split and its implications to their respective team members. Many employees reportedly agreed to the transfer.

- For X et al., who chose to be represented by their labor union branch, Y Corp held seven distinct consultation sessions with the union representatives and also engaged in written correspondence.

Despite these consultations, X et al. felt that Y Corp had not adequately fulfilled its obligations. After the company split took effect and their employment contracts were formally transferred to C Corp, X et al. filed a lawsuit against their original employer, Y Corp. They sought a court declaration that their employment relationship continued with Y Corp, arguing that the transfer of their contracts to C Corp was invalid, primarily because Y Corp had breached its Article 5 consultation duties. (They also made a claim for damages in tort, which is not the focus here). Both the court of first instance and the appellate court dismissed their claims. X et al. then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: Labor Contract Succession Act (LCSA) and the Article 5 Consultation Duty

Understanding the Supreme Court's decision requires a brief overview of the relevant legal provisions:

- Labor Contract Succession Act (LCSA): This Act (formally, the "Act on Succession, Etc. of Labor Contracts Incidental to Company Split") sets out the rules for how employment contracts are handled in company splits.

- Article 3 (Automatic Succession for "Primarily Engaged" Employees): If an employee is "primarily engaged in the business to be succeeded to" and the company split plan states that their employment contract will be transferred to the successor company, the contract is indeed transferred. Critically, for such employees, Article 3 does not provide a right to object to this specific determination that their contract will be transferred with the business they are primarily part of.

- Employee Objection Rights (LCSA Articles 4 & 5): The LCSA does provide objection rights in other scenarios:

- If an employee primarily engaged in the transferred business is excluded by the split plan from being transferred, they can object and typically will then be transferred (Article 4).

- If an employee not primarily engaged in the transferred business is included in the split plan for transfer, they can object and typically will then not be transferred (Article 5).

- Article 5 Consultation (Supplementary Provisions, Act Amending Commercial Code): This provision mandated that the splitting company consult with its employees regarding the succession of their labor contracts before the official lodging of the split plan documents (which contain the definitive list of transferring contracts). The aim was to allow employee input into the company's decision-making process concerning whose contracts would transfer.

The situation of X et al. fell under LCSA Article 3: they were deemed by Y Corp to be primarily engaged in the HDD business, and the split plan stipulated their transfer. Thus, their main procedural protection, and the focus of the legal battle, was the adequacy of the pre-split Article 5 consultation.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Defining the Stakes of Consultation

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated July 12, 2010, ultimately dismissed X et al.'s appeal, finding that the transfer of their employment contracts to C Corp was valid. However, in reaching this conclusion, the Court made several crucial pronouncements about the Article 5 consultation duty and its legal effect:

- Purpose of the Article 5 Consultation: The Court emphasized that the legislative intent behind requiring the Article 5 consultation was to protect employees. Given that the succession (or non-succession) of an employment contract in a company split can bring about significant changes to an employee's status, the law requires the splitting company to engage in discussions with individual employees whose work is part of the business being transferred before the company finalizes its decisions on which contracts will succeed. This process is meant to allow the company to consider the employees' wishes and perspectives when making these critical determinations.

- LCSA Article 3 Presupposes a Proper Article 5 Consultation: The Supreme Court reasoned that LCSA Article 3 – which provides for the automatic transfer of employment contracts for "primarily engaged" employees designated in the split plan, without a right for those specific employees to object to that designation – implicitly presumes that an appropriate and meaningful Article 5 consultation has already taken place, and that the employees' interests have been duly considered and protected through that prior consultation process.

- Consequences of a Defective Article 5 Consultation (The Core Holding): Building on this, the Court outlined the legal consequences if the Article 5 consultation duty is breached:

- No Consultation Conducted at All: If, with respect to a particular employee who falls under LCSA Article 3 (i.e., primarily engaged and designated for transfer), the splitting company conducted no Article 5 consultation whatsoever, then that employee can contest the validity of the succession of their labor contract as stipulated by LCSA Article 3.

- Grossly Insufficient Consultation: Even if some form of consultation did take place, if the explanations provided by the splitting company or the nature of the discussions were so grossly insufficient that they clearly contravene the legislative purpose of the Article 5 consultation requirement, this would constitute a breach of the consultation duty. In such a case, the affected employee can also contest the validity of the labor contract succession under LCSA Article 3.

- Application to Y Corp's Case: Despite establishing these strong principles, the Supreme Court concluded that, in the specific circumstances of X et al., Y Corp's Article 5 consultation efforts, conducted primarily through their union branch, were not "grossly insufficient."

- The Court noted that Y Corp had explained matters such as the business overview of the new company (C Corp) and the basis for determining that X et al. were employees primarily engaged in the transferring HDD business. This was seen as aligning with the spirit of Ministry guidelines on such consultations.

- While Y Corp did not provide answers in the exact form requested by the union for certain matters (e.g., detailed financial projections for C Corp, which Y Corp cited as confidential business information) and did not accede to requests for X et al. to be given alternative arrangements like secondment to C Corp or internal transfers within Y Corp, the Supreme Court found that Y Corp had reasonable grounds for its positions. For example, refusing alternatives like secondment was understandable given the split's purpose as part of a JV integration plan which envisioned a full transfer of the HDD workforce.

- Therefore, the Court held that the consultations, while not satisfying all of X et al.'s demands, were not so deficient as to render the transfer of their employment contracts to C Corp invalid.

- Status of LCSA Article 7 (Duty to Strive for Employee Understanding and Cooperation): The Court clarified that Article 7 of the LCSA, which obligates the splitting company to "endeavor to obtain the understanding and cooperation" of its employees regarding the split, imposes an "endeavor obligation" (doryoku gimu) rather than a strict legal duty with direct nullifying consequences. A breach of Article 7, in itself, would not invalidate the labor contract succession. Deficiencies in Article 7 measures might only become relevant as one factor in assessing whether the mandatory Article 5 consultation was substantively adequate, particularly if poor Article 7 efforts undermined the Article 5 process. In this case, Y Corp's broader efforts under Article 7 (such as providing information via intranet and holding meetings with employee representatives) were deemed sufficient.

- The Role of Ministry Guidelines: The Supreme Court acknowledged the existence of Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare guidelines (指針 - shishin) that detail the types of information to be provided and matters to be discussed during Article 7 measures and Article 5 consultations. The Court stated that these guidelines are generally reasonable, and in assessing whether a company's consultation efforts meet the legal requirements, due consideration should be given to whether those efforts aligned with the guidelines.

Analysis and Implications

This 2010 Supreme Court decision was a landmark in clarifying the legal significance of the pre-split employee consultation process in Japan:

- Empowerment of Employees – The "Relative Effect Theory": The most significant implication is the Court's adoption of what legal scholars term the "relative effect theory" (sōtaikōsetsu). This means that serious defects in the Article 5 consultation concerning a specific employee can render the transfer of that employee's individual contract invalid, even if the company split itself remains valid for other employees and for corporate law purposes. This provides a more targeted and meaningful remedy for affected employees than, for instance, having to seek the nullification of the entire corporate reorganization.

- Setting a Standard (Albeit a High One): The Court established that either a complete absence of consultation or a "grossly insufficient" consultation can invalidate the automatic succession of an employment contract under LCSA Article 3. While "grossly insufficient" is a high threshold, it provides a judicial standard for reviewing the adequacy of these mandatory consultations. It signals that the Article 5 consultation is not a mere procedural formality but has substantive importance.

- Guidance for Companies Undertaking Splits: The decision underscores the necessity for companies planning splits to take their Article 5 consultation obligations very seriously. They must engage genuinely with affected employees (or their representatives), provide adequate information about the new entity and the reasons for transfer, and listen to employee concerns, even if they are not legally bound to agree to all employee demands. Adherence to Ministry guidelines is also an important factor.

- Focus on "Primarily Engaged" Employees without Objection Rights: The ruling is particularly relevant for employees who are deemed "primarily engaged" in the transferring business and are designated for transfer in the split plan. Since LCSA Article 3 does not grant these employees a right to object to their transfer if these conditions are met, the integrity of the prior Article 5 consultation becomes their principal procedural safeguard.

- Unresolved Issues and Ongoing Considerations:

- Defining "Grossly Insufficient": Future case law will need to further delineate what constitutes "grossly insufficient" consultation. The specific information that must be disclosed, especially concerning the financial prospects or future working conditions of the successor company, remains a point of potential contention, balanced against legitimate business confidentiality concerns.

- Changes to Working Conditions Post-Transfer: The LCSA framework primarily aims to ensure that employment contracts are transferred on their existing terms. However, any subsequent changes to working conditions by the successor company (especially if disadvantageous) would be governed by general labor law principles, such as the need for employee consent or the rules concerning unilateral changes to work rules. The Article 5 consultation might touch upon expected future conditions, but the legal regime for implementing changes post-transfer is distinct.

- Scope of "Business" in Splits under the Current Companies Act: This case was decided under the old Commercial Code provisions. The current Companies Act (effective 2006) defines the subject of a split more broadly as "all or part of the rights and obligations it [the company] holds in connection with its business." This could potentially mean that if a very limited set of assets and liabilities (not forming an organic "business" unit) is transferred, it might be harder to identify any employee as "primarily engaged" in it. In such a scenario, any employee whose contract is nevertheless included for transfer might have objection rights under LCSA Article 5, making the LCSA Article 3 / Article 5 consultation dynamic less critical for them.

Conclusion

The July 12, 2010, Supreme Court decision solidified the importance of the Article 5 consultation as a crucial element of employee protection in Japanese company splits. It clarified that while the LCSA facilitates the transfer of employment contracts without individual consent in many cases, this is predicated on the splitting company having engaged in a proper and meaningful prior consultation with the affected employees. A complete failure to consult, or a consultation process so deficient that it undermines the legislative intent of protecting employees, can empower an individual employee to successfully challenge the transfer of their employment contract to the successor company. This ruling strikes a balance between facilitating corporate restructuring and safeguarding the rights and interests of employees caught in these transitions.