Employee or Independent Contractor? Classifying Entertainers Under Japanese Labor Law

TL;DR

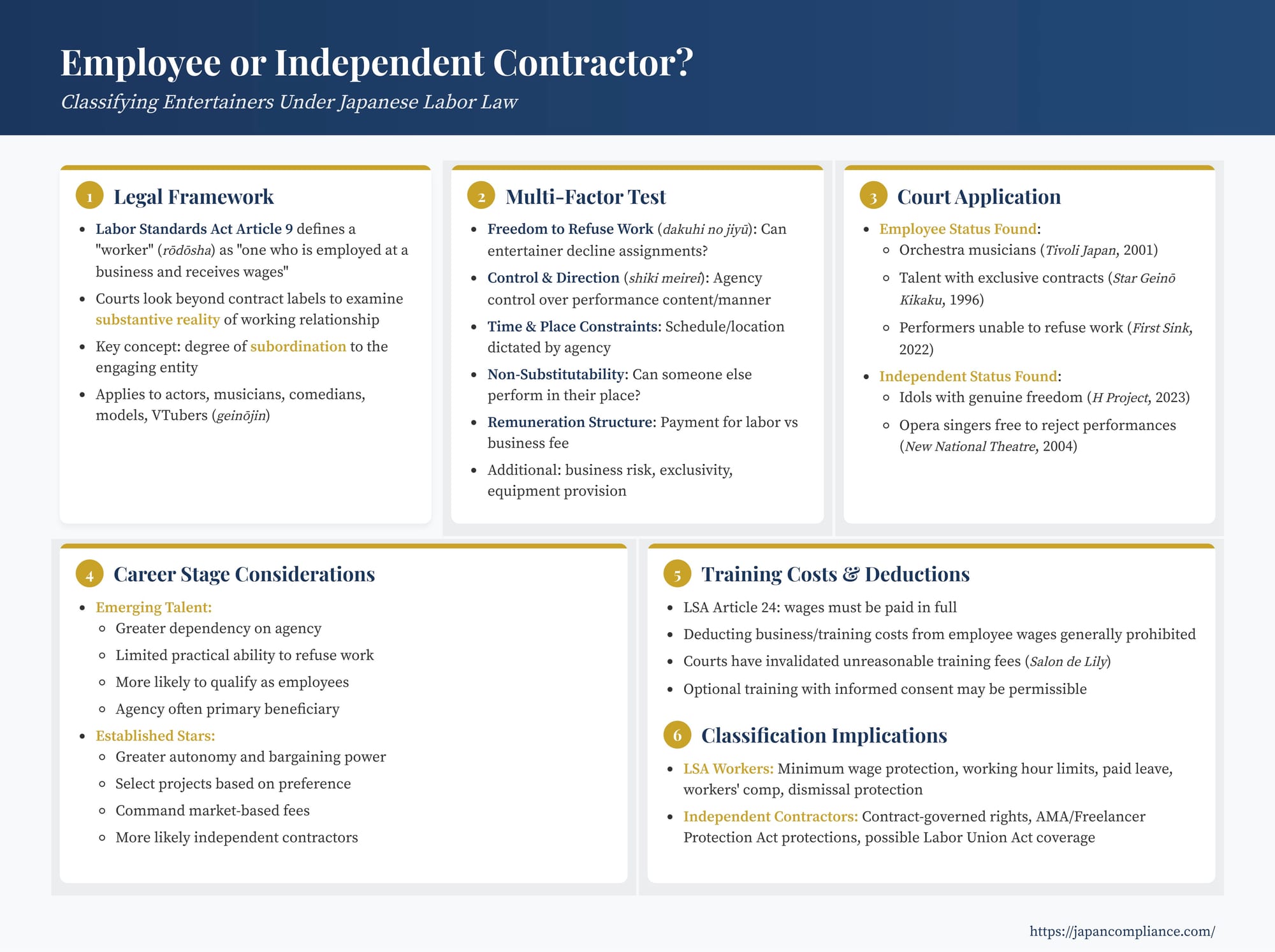

- Japan applies a multi-factor test—freedom to refuse work, control, exclusivity, remuneration type, etc.—to decide if an entertainer is an LSA “worker.”

- Recent cases show emerging talent is often deemed employees, while established stars may remain independent contractors.

- Classification drives wage, overtime, social-insurance and training-cost obligations, so agencies and foreign studios must draft contracts carefully.

Table of Contents

- The Legal Framework: Defining a "Worker"

- The Multi-Factor Test for LSA Worker Status

- How Japanese Courts Have Applied the Test to Entertainers

- Special Considerations for Emerging vs. Established Talent

- Training Costs and Deductions

- Implications of Classification

- Conclusion

The legal status of individuals in the entertainment industry—actors, musicians, comedians, models, VTubers, and others (geinōjin, 芸能人)—often exists in a grey area between traditional employment and independent contracting. In Japan, determining whether an entertainer is considered a "worker" (労働者, rōdōsha) under labor law carries significant consequences for both the talent and the engaging entity (like a management agency, geinō jimusho, or production company). This classification dictates the applicability of fundamental protections concerning working hours, minimum wage, social insurance, and termination rights.

The Legal Framework: Defining a "Worker"

The primary definition comes from Japan's Labor Standards Act (LSA - 労働基準法, Rōkihō). Article 9 defines a "worker" as one who is employed at a business or office and receives wages therefrom, regardless of the type of occupation. This definition is crucial for accessing core labor protections.

Japanese courts don't rely solely on the title or label used in a contract (e.g., "management agreement" vs. "employment contract"). Instead, they conduct a fact-based analysis, weighing multiple factors to determine the substantive reality of the working relationship and assess the degree of subordination to the engaging entity.

The Multi-Factor Test for LSA Worker Status

Based on established case law and administrative guidance, the key factors considered include:

- Freedom to Accept or Refuse Work Requests (諾否の自由, Dakuhi no Jiyū): Does the entertainer have genuine freedom to turn down specific job offers or assignments from the agency/company without significant penalty or disadvantage? A lack of such freedom strongly indicates employee status.

- Control and Direction over Work Performance (指揮命令, Shiki Meirei): Does the agency/company exert significant control over the content and manner of the work performed? This includes detailed instructions regarding performance style, scheduling, location, and participation in related activities (e.g., rehearsals, promotional events). Extensive direction points towards employment.

- Constraints on Working Time and Place (時間的・場所的拘束性, Jikanteki/Bashoteki Kōsokusei): Are the entertainer's working hours and locations largely dictated by the agency/company? Being bound to specific schedules (beyond what's inherent in a performance itself) or required presence at company facilities suggests employment.

- Non-Substitutability (代替性, Daitaisei): Can the entertainer arrange for someone else to perform their role? Given the personal nature of entertainment services, this factor almost always points towards employment, as performances are typically non-substitutable. However, this factor alone is rarely decisive.

- Remuneration as Payment for Labor (報酬の労務対価性, Hōshū no Rōmu Taikasei): Is the payment primarily compensation for the labor provided (time spent, tasks completed), resembling wages, or is it more akin to a business fee for achieving a specific result or based on profit-sharing? Payment structures directly linked to time or effort expended suggest employment.

- Other Indicators: Courts also consider:

- Bearing of Business Risk (事業者性, jigyōshasei): Does the entertainer bear significant financial risk, or is it primarily borne by the agency? Lack of risk for the entertainer points towards employment.

- Exclusivity (専属性, senzokusesei): Is the entertainer heavily restricted from working for other companies? High exclusivity suggests employment.

- Provision of Equipment: Does the agency provide necessary equipment, costumes, or facilities?

- Administrative Treatment: Is income tax withheld at source? Is the entertainer covered by social insurance schemes (health, pension, unemployment)? These factors can be indicative but are not conclusive.

No single factor determines the outcome; courts perform a holistic assessment of the relationship's substance.

How Japanese Courts Have Applied the Test to Entertainers

Case law reveals diverse outcomes depending on the specific facts:

- Finding Employee Status: Courts have recognized LSA worker status in cases involving:

- Orchestra musicians under exclusive contract (Tivoli Japan, Okayama Dist. Ct. 2001).

- Talent whose 10-year exclusive contract was shortened under LSA limits (Star Geinō Kikaku, Tokyo Dist. Ct. 1996).

- Performers under exclusive contracts where minimum wage laws were deemed applicable (J Company et al., Tokyo Dist. Ct. 2009).

- Talent whose agency contract included penalties for refusing work, negating practical freedom to refuse (First Sink, Osaka Dist. Ct. 2022).

- Theater group members who, despite a theoretical right to refuse roles, were practically unable to do so due to reliance on the group for work and training (Air Studio, Tokyo High Ct. 2021).

- Denying Employee Status: LSA worker status has been denied where:

- Idols were found to have genuine freedom to refuse participation in specific events (H Project, Tokyo High Ct. 2023).

- Contracted opera singers had the freedom to accept or reject individual performance offers from the theater foundation (New National Theatre Foundation, Tokyo High Ct. 2004).

Key Factors in Entertainment:

- Freedom to Refuse Work: This factor frequently proves decisive. However, as the Air Studio case suggests, courts may look beyond theoretical freedom. If refusing work, while technically possible, would severely jeopardize the entertainer's career development, training opportunities, or relationship with the sole provider of work, the court might find substantive freedom lacking. This is particularly relevant for emerging artists heavily reliant on their agency.

- Remuneration Structure: Fixed salaries clearly favor employee status. However, payment based on performance outcomes (e.g., percentages of appearance fees, revenue sharing, "ticket back" systems where performers sell tickets and keep a portion) traditionally points towards independent contractor status. Yet, courts may find employee status even with such structures if, overall, the relationship exhibits strong subordination (e.g., First Sink). The argument exists that for fledgling artists, non-traditional pay like ticket-back systems might reflect the agency minimizing its own risk rather than true entrepreneurial activity by the talent.

Special Considerations for Emerging vs. Established Talent

The multi-factor test might yield different results depending on the entertainer's career stage.

- Emerging Talent: Individuals just starting out, often heavily dependent on their agency for training, promotion, securing auditions/roles, and financial support, are arguably in a position of greater subordination. Their practical ability to refuse work or negotiate terms may be minimal. For these individuals, the balance of factors often leans more strongly towards finding LSA worker status to ensure baseline protections like minimum wage and working hour regulations. The "primary beneficiary" of the relationship at this stage could arguably be seen as the agency investing in potential future returns.

- Established Stars: Highly successful entertainers with significant name recognition, established fan bases, and greater bargaining power may operate with more autonomy. They might genuinely select projects, command high fees based on their market value rather than time worked, and employ their own support staff. In such cases, the factors might point more strongly towards independent contractor status.

Training Costs and Deductions

A related issue involves agencies requiring trainees or developing talent to bear the costs of essential training (lessons, etc.) or other necessary business expenses. If an entertainer is classified as an LSA employee:

- Wage Payment Principles: LSA Article 24 requires wages to be paid in full, directly to the worker. Deducting business expenses or mandatory training costs from wages is generally prohibited unless explicitly permitted by a collective labor agreement.

- Reasonableness: Even with an agreement, charging employees for training essential to perform their duties can be problematic. Courts have invalidated arrangements where training fees were deemed costs the employer should rightfully bear as part of standard employee development (e.g., the Salon de Lily case involving beautician training, Urawa Dist. Ct. 1985). However, if training is truly optional, provides general skills beyond the immediate job, and the cost-bearing arrangement is based on free and informed consent, it might be permissible.

Implications of Classification

The distinction between employee and independent contractor is critical:

- Employees (LSA Workers): Benefit from the full suite of Japanese labor law protections, including minimum wage, statutory limits on working hours, mandatory overtime premiums, paid annual leave, eligibility for workers' compensation insurance (rōsai hoken), and stronger protections against unfair dismissal (under the Labor Contract Act). They are typically covered by mandatory social insurance (health, pension, unemployment).

- Independent Contractors: Fall outside LSA/LCA protections. Their rights and obligations are governed primarily by their contracts. They may receive some protection against unfair practices under the AMA (especially ASBP) or the new Freelancer Protection Act (regarding contract clarity and payment terms). They might also qualify as "workers" under the broader definition of the Labor Union Act, granting them rights to organize and bargain collectively.

Conclusion

Classifying entertainers in Japan remains a nuanced, case-by-case determination based on the substantive reality of the working relationship. While the freedom to refuse work and the degree of control exercised by the engaging entity are often key indicators, courts consider a range of factors. There is a discernible trend, particularly supported by lower court decisions and legal commentary, suggesting that emerging entertainers heavily reliant on their agencies may warrant classification as LSA workers deserving of fundamental labor protections. In contrast, established stars operating with significant autonomy may more closely resemble independent contractors. Given the significant legal and financial consequences tied to this classification, both talent and the businesses engaging them must carefully consider the nature of their relationship and structure their agreements accordingly.

- Talent Mobility in Japan’s Entertainment Industry: Antitrust Risks & Contract Tips

- Protecting Stardom in Japan: Publicity Rights for Stage & Group Names

- Digital Doubles in Japan: Legal Guide to AI Avatars, Privacy & Portrait Rights for Entertainers

- MHLW Guidance on Worker/Contractor Classification (Japanese)

- Freelancer Protection Act Outline (Cabinet Office, Japanese)