Employee Mistakes, Employer Losses: Japan's Ibaraki Sekitan Case and Limits on Recovery

When an employee's actions in the course of their duties lead to financial loss for the employer—either through direct damage to company property or by incurring liability to third parties—a crucial question arises: to what extent can the employer seek compensation from the employee? While employees are expected to perform their duties with care, Japanese labor law, through judicial precedent, has established that an employer's right to claim damages or seek indemnification from an employee is not unlimited. The Supreme Court of Japan's decision in the Ibaraki Sekitan Shoji case on July 8, 1976, stands as a landmark ruling, articulating the principle that such claims are subject to limitations based on fairness and good faith.

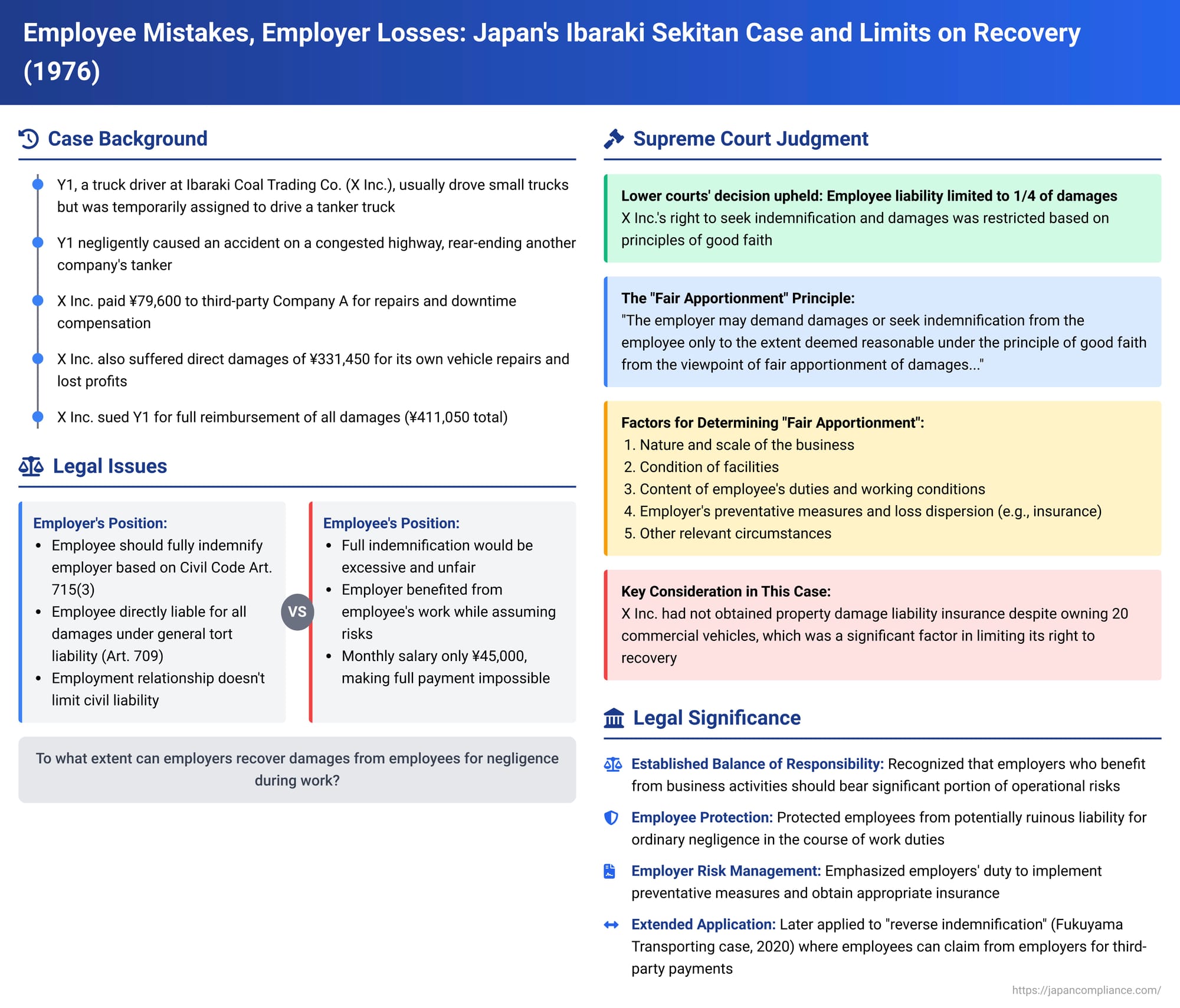

The Ibaraki Sekitan Shoji Incident: A Costly Truck Accident

The case involved Y1, a truck driver employed by X Inc. (Ibaraki Coal Trading Co.), a company engaged in the transportation and sale of coal and other fuels. Y1 primarily drove small cargo trucks but was on one occasion temporarily assigned to operate one of X Inc.'s tanker trucks. While driving this tanker, nearly full of heavy oil on a national highway where traffic was beginning to congest, Y1 negligently failed to maintain a safe following distance and pay sufficient attention to the road ahead. As a result, he rear-ended another tanker truck owned by a third-party company, Company A, causing damage to Company A's vehicle.

X Inc. reached a settlement with Company A, paying a total of 79,600 yen to cover the costs of repairing Company A's truck and compensating for its downtime during the repair period. In addition to this, X Inc. suffered its own direct losses amounting to 331,450 yen, which included the repair costs for its own tanker and lost profits while its vehicle was out of service.

Following these events, X Inc. filed a lawsuit against Y1. The company sought indemnification from Y1 for the amount it had paid to Company A (based on Article 715, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Code, which allows employers to seek reimbursement from employees after compensating for the employee's tort against a third party). X Inc. also claimed direct damages from Y1 for the losses it had personally sustained (based on Article 709 of the Civil Code, concerning general tort liability). The lawsuit also included Y1's personal guarantors, Y2 and Y3.

The lower courts, including the Tokyo High Court, found Y1 liable but significantly limited X Inc.'s recovery. The High Court affirmed the trial court's (Mito District Court) decision that X Inc.'s right to seek indemnification and damages from Y1 should be restricted to one-fourth (1/4) of the total losses incurred. The courts reasoned that claiming an amount exceeding this limit would violate the principle of good faith (信義則 - shingisoku) and constitute an abuse of rights. Dissatisfied with this limitation, X Inc. appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 1976 Ruling: Establishing the "Fair Apportionment" Principle

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed X Inc.'s appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decision to limit the employee's liability to one-fourth of the damages. In its judgment, the Court laid down a foundational principle for such cases:

"Where an employer has suffered direct damage or has incurred damage due to bearing liability as an employer for compensation for damages with respect to an employee's tortious act committed in the execution of the employer's business, the employer may demand damages or seek indemnification from the employee only to the extent deemed reasonable under the principle of good faith from the viewpoint of fair apportionment of damages, in light of the nature and scale of the business, the condition of its facilities, the content of the employee's duties, working conditions, work attitude, the nature of the tortious act, the degree of the employer's care in preventing the tortious act or in dispersing losses, and all other relevant circumstances."

Application of the Principle to Y1's Case:

The Supreme Court reviewed the specific facts upheld by the lower court:

- X Inc. (Employer): A company with a capital of 8 million yen, employing about 50 people, and owning nearly 20 commercial vehicles, including tanker trucks and small cargo trucks. Crucially, for cost-saving reasons, X Inc. had only secured third-party personal injury liability insurance for its vehicles; it had not obtained third-party property damage liability insurance or insurance for damage to its own vehicles.

- Y1 (Employee): Primarily assigned to drive small cargo trucks and was only temporarily tasked with driving the tanker truck involved in the accident. The accident occurred due to Y1's negligence (insufficient following distance and attention) while operating a heavily laden tanker on a congested highway. At the time, Y1's monthly salary was approximately 45,000 yen, and his work performance record was considered "average or better."

Considering these circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded that limiting X Inc.'s claim for damages and indemnification against Y1 to one-fourth of the total amount of loss was indeed appropriate and justifiable under the principle of good faith.

Underlying Rationale for Limiting Employee Liability

While the Supreme Court's judgment explicitly invoked the "principle of good faith" and "fair apportionment of damages," legal commentary elaborates on the substantive rationale behind limiting an employee's liability in such situations. Key underlying concepts include:

- Reward Liability (報償責任 - hōshō sekinin): Employers derive profits and benefits from the activities of their employees. As such, it is considered fair that they also bear a portion of the risks and losses inherent in those activities.

- Risk Creation/Control (危険責任 - kiken sekinin): Employers create the business environment, define the scope of operations, and largely control the conditions under which work is performed. By expanding their business activities through employees, they inherently increase the risk of causing harm or loss. Therefore, they should bear primary responsibility for managing and mitigating these risks.

- Employee's Position: Employees typically operate under the direction and orders of their employer and often have limited financial capacity to cover substantial business losses. Their subordinate position and the fact that their labor is a factor in the employer's profit-making enterprise are also relevant considerations.

Key Factors in Practice (Post-Ibaraki Sekitan)

The Ibaraki Sekitan Shoji ruling provided a multi-factor test, and subsequent court decisions have further illuminated how these factors are weighed:

- Employer's Preventative Measures and Loss Dispersion (Factor 4): This is often a critical element. Courts heavily scrutinize the employer's efforts to prevent such incidents and to mitigate potential losses. A particularly significant aspect is whether the employer carried adequate insurance. X Inc.'s failure to have property damage and vehicle insurance was a major consideration in limiting its recovery from Y1. Other preventative measures include proper training, supervision, safety protocols, and addressing overly harsh working conditions that might contribute to errors.

- Employee's Degree of Culpability (Factor 3): While intentional wrongdoing or gross negligence by an employee is treated more seriously than simple negligence, even in cases of simple negligence, employees are not automatically absolved of all liability. The level of negligence is one factor among many. Conversely, even in instances of an employee's intent or gross negligence, courts may still limit the employer's recovery if other factors, such as the employer's insufficient preventative measures, are present.

- Nature of Work and Foreseeable Risks (Factors 1 & 2): Minor errors or operational mishaps that are reasonably foreseeable in the course of normal business operations are often viewed as risks that the employer should primarily bear. The fact that Y1 was only temporarily assigned to the more demanding task of driving a tanker truck was considered a factor in his favor.

- Employee's Working Conditions and Attitude (Factor 2): The employee's salary level is frequently taken into account, especially when contrasted with the magnitude of the damages claimed. A good work record and attitude, as Y1 reportedly had, can also be a mitigating factor.

- Other Circumstances (Factor 5): Courts may also consider whether the employee was given an opportunity to explain their actions, how the employer has handled similar incidents in the past, and whether other disciplinary measures (short of demanding full compensation) have already been taken.

Evolution of the Doctrine: "Reverse Indemnification"

The principles established in the Ibaraki Sekitan Shoji case have had a lasting impact and have even been extended. While the 1976 ruling focused on the employer's claim against the employee, a more recent Supreme Court decision has addressed the scenario of "reverse indemnification" (逆求償 - gyaku-kyūshō).

In the Fukuyama Transporting case (Supreme Court, February 28, 2020), the Court affirmed that an employee who, in the course of executing the employer's business, personally compensates a third party for damages caused, may then seek indemnification from the employer. This right to reverse indemnification is also subject to limitations based on the principle of fair apportionment of loss, considering the same types of factors outlined in the Ibaraki Sekitan Shoji decision. This development reinforces the idea that the ultimate responsibility for losses arising from business operations is shared, with the employer often bearing the larger portion due to their role in creating and controlling the enterprise.

Conclusion

The Ibaraki Sekitan Shoji case is a cornerstone in Japanese labor law, establishing the vital principle that an employee's liability to their employer for damages caused during work is not absolute. Instead, it is governed by the principle of good faith and requires a "fair apportionment of loss." This involves a comprehensive assessment of various factors, with particular emphasis on the employer's own measures to prevent losses and disperse risks, most notably through adequate insurance coverage. The ruling reflects a balancing act, acknowledging that while employees have a duty of care, the employer, as the beneficiary of the business and the entity creating and controlling operational risks, should ultimately bear a significant share of losses arising from routine human error in the workplace. This doctrine continues to shape how financial responsibility for workplace incidents is allocated in Japan.