Employee Inventions in Japan: Ownership, “Reasonable Benefit,” and Best-Practice Procedures

TL;DR

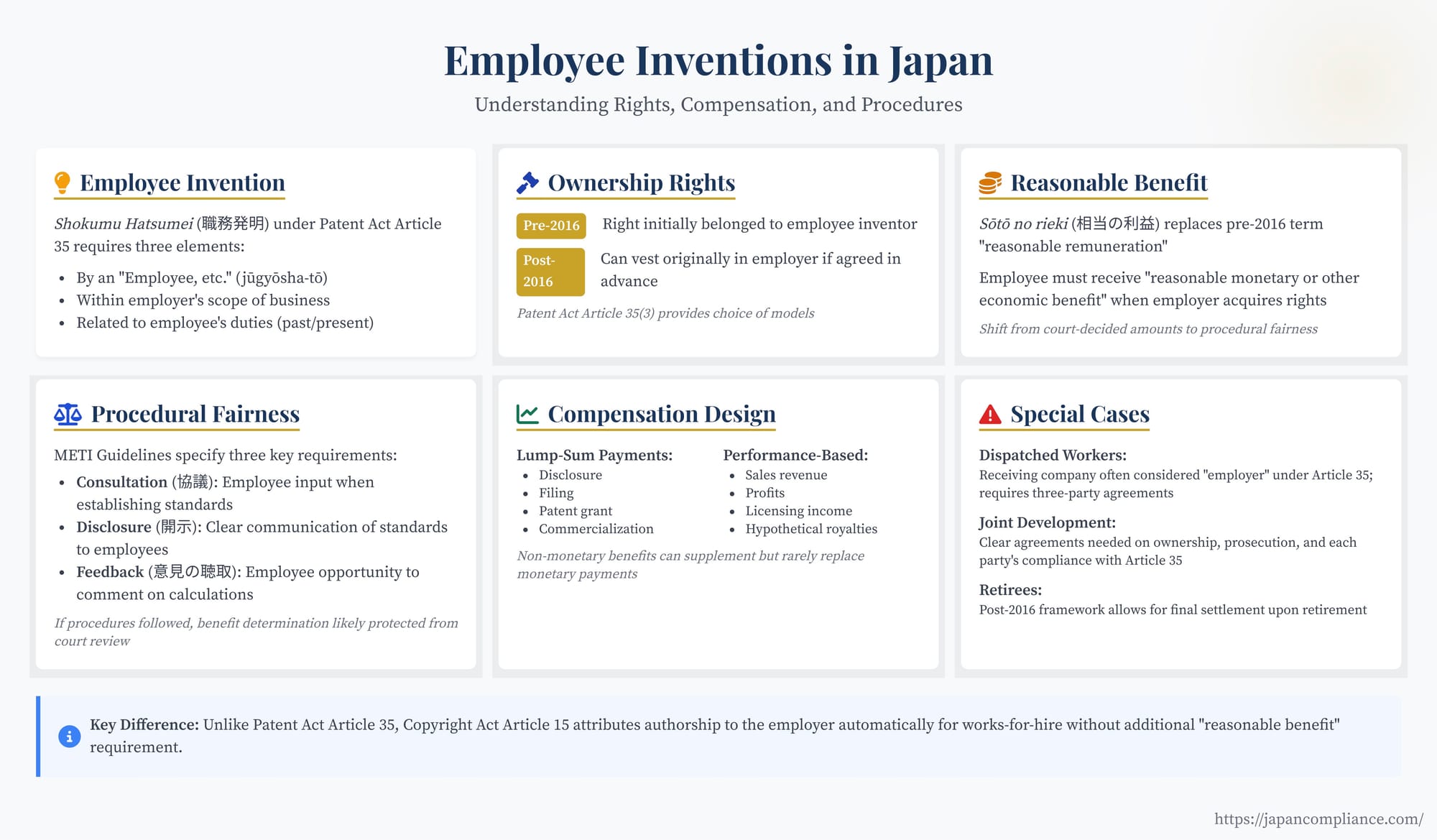

- Japan’s Patent Act lets employers claim rights to employee inventions if advance contracts or work rules so provide, but inventors still deserve a “reasonable benefit.”

- Since 2016, courts focus on procedural fairness—consultation, disclosure, and feedback—when judging whether benefit levels are reasonable.

- Clear, transparent internal rules save litigation risk and hefty awards like past “blue-LED” cases.

- Special care is needed for dispatched workers, freelancers, retirees, and joint-development projects.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Fostering Innovation Through Law

- What Is an “Employee Invention”?

- Ownership Rules After the 2016 Amendments

- The Inventor’s Right to “Reasonable Benefit”

- Procedural Fairness Requirements & METI Guidelines

- Designing Compensation Systems

- Who Counts as an “Employee”? (Dispatch, Freelance, etc.)

- Handling Retirees and Joint R&D

- Copyright Works vs. Patent Inventions

- Conclusion: Procedural Fairness Is Paramount

Introduction: Fostering Innovation Through Law

Innovation is the lifeblood of competitive businesses, and employee inventions are often a primary source of valuable intellectual property. Recognizing the importance of both encouraging invention and clarifying ownership, Japan has a specific legal framework governing inventions created by employees within the scope of their work. Governed primarily by Article 35 of the Patent Act, this framework addresses the critical issues of who owns the rights to an employee invention and what compensation or benefit the employee inventor is entitled to receive.

Significant amendments to Article 35 came into effect in 2016, fundamentally altering the approach to ownership and compensation. Understanding this revised system is crucial for any company, including US subsidiaries or partners, conducting research and development activities or employing inventors in Japan. Failure to comply with the procedural requirements, particularly concerning the determination of employee benefits, can lead to disputes and legal challenges.

This article provides an overview of Japan's employee invention system, covering the definition of an employee invention (shokumu hatsumei), the rules governing ownership, the employee's right to "reasonable benefit" (sōtō no rieki), the critical role of procedural fairness and internal regulations, and practical considerations for handling different types of workers and collaborations.

What Qualifies as an "Employee Invention" (Shokumu Hatsumei)?

Article 35, Paragraph 1 of the Patent Act defines an employee invention based on three cumulative criteria:

- Invention by an "Employee, Etc.": The invention must be made by an employee, officer, or civil servant (collectively referred to as "employee, etc." - jūgyōsha-tō). This scope is interpreted broadly and includes not just regular full-time employees but potentially also part-time workers, contract employees, and dispatched workers under certain circumstances (discussed further below).

- Within the Employer's Scope of Business: The nature of the invention itself must fall within the scope of the employer's current or past business activities. This is generally interpreted broadly.

- Related to Employee's Duties: The act(s) that led to the invention must fall within the employee's present or past duties performed for the employer. This connection between the invention and the employee's assigned responsibilities is key.

Inventions made by employees that meet all three criteria are classified as shokumu hatsumei and are subject to the specific rules of Article 35. Inventions made by employees that fall within the employer's business scope but are not related to their duties, or inventions unrelated to the employer's business scope altogether, are treated differently (generally considered the employee's personal invention, though shop rights or contractual obligations might still apply).

Ownership of Invention Rights: The Shift Since 2016

A major change introduced by the 2015 amendments (effective April 2016) relates to the initial ownership of the right to obtain a patent for an employee invention.

- Pre-2016 Default: Under the old law, the right to obtain a patent originally belonged to the employee inventor by default (based on Patent Act Article 29(1)). Employers typically secured these rights through clauses in employment contracts or work rules that stipulated a pre-assignment (a promise by the employee to assign the rights to the employer).

- Post-2016 Options (Article 35(3)): The revised Article 35(3) provides more flexibility. While the default rule (employee ownership) still applies if nothing else is agreed upon, employers can now stipulate in advance—through employment contracts, work rules, or other agreements—that the right to obtain a patent for an employee invention shall originally vest in the employer.

This means companies in Japan can now choose between two main models:

- Employee-First Model: The right initially belongs to the employee, who then assigns it to the employer based on a contractual obligation (often in exchange for compensation).

- Employer-First Model: The right belongs to the employer from the moment the invention is created, provided a valid prior agreement (e.g., in the work rules) exists.

Regardless of which model is used (assignment from employee or initial vesting in the employer), the fundamental obligation to provide a benefit to the employee inventor remains.

The Employee's Entitlement: "Reasonable Benefit" (Sōtō no Rieki)

When an employer acquires the right to obtain a patent for an employee invention (either through assignment or initial vesting), Article 35(4) mandates that the employee is entitled to receive "reasonable monetary or other economic benefit" (相当の金銭その他の経済上の利益 – sōtō no kinsen sono ta no keizai-jō no rieki), often referred to simply as "reasonable benefit" (sōtō no rieki).

This concept replaced the pre-2016 term "reasonable remuneration" (sōtō no taika). While the change in terminology might seem subtle, it accompanied a crucial shift in how the adequacy of the employee's compensation is assessed.

The Crucial Role of Procedural Fairness (Article 35(5) & METI Guidelines)

The most significant change introduced in 2016 relates to how the reasonableness of the benefit is determined. Under the old system, courts often engaged in a substantive review, calculating what they considered "reasonable remuneration" based primarily on the employer's profits from the invention and frequently overriding company compensation schemes if deemed insufficient (famously leading to very large awards in some cases, like the blue LED litigation prior to the amendment).

The revised Article 35(5) shifts the focus from the substantive adequacy of the benefit amount to the procedural fairness used by the employer in determining that benefit. It states that the benefit determined according to standards set forth in advance (e.g., in work rules or employment contracts) shall not be considered unreasonable if the process of establishing those standards meets certain procedural fairness requirements.

Article 35(6) tasks the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) with establishing guidelines concerning these procedures. The METI Guidelines (formally: "Guidelines concerning procedures related to consultations, etc. between employer, etc. and employee, etc. to be considered when stipulating provisions on reasonable monetary or other economic benefits for employee inventions") emphasize three key procedural elements:

- (Consultation) Setting the Standards: The process for establishing the standards for calculating benefits must involve consultations (協議 - kyōgi) between the employer and employees (or their representatives). This aims to ensure employee perspectives are considered when the compensation framework is created or revised.

- (Disclosure) Disclosing the Standards: The established standards must be disclosed (開示 - kaiji) to the employees in a clear and accessible manner (e.g., through work rules, intranet). Employees need to know how their benefits will be determined.

- (Feedback) Calculating Individual Benefits: When calculating the specific benefit for a particular invention, the employer must provide an opportunity for the relevant employee inventor(s) to express opinions (意見の聴取 - iken no chōshu) regarding the calculation. This doesn't necessarily mean negotiation is required for every payment, but the employee should have a chance to understand the calculation and raise questions or concerns.

Consequences of Procedural Flaws: If an employer determines the benefit based on internal standards but failed to follow these procedural requirements (e.g., set the standards unilaterally without consultation, failed to disclose them properly, or denied employees the chance to provide feedback on calculations), then Article 35(5) does not apply. In such cases, if an employee challenges the benefit as unreasonable, a court can intervene. The court would then determine the reasonable benefit amount itself, considering factors like the profits the employer obtains from the invention, the employer's contribution (e.g., R&D investment, facilities), the employee's contribution, and the employee's treatment (Article 35(7)).

This procedural safe harbor is a major incentive for companies to establish and follow fair internal processes for their employee invention systems.

Designing Employee Invention Compensation Systems

The current framework offers companies considerable flexibility in designing their "reasonable benefit" systems, provided the procedural requirements are met. Common approaches include:

- Lump-Sum Payments: Providing fixed payments at certain milestones, such as:

- Invention disclosure

- Patent application filing

- Patent grant (in Japan or key foreign countries)

- Upon commercialization

- At retirement (as a potential final settlement)

- Performance-Based Payments (Royalties): Calculating payments based on the success of the invention, often tied to:

- Sales revenue of products incorporating the invention.

- Profits generated by the invention.

- Licensing income received from third parties.

- Calculated "hypothetical royalty rates" based on industry standards.

- Non-Monetary Benefits: While Article 35(4) refers to "monetary or other economic benefit," the METI Guidelines clarify that non-monetary benefits (e.g., stock options, promotions, paid leave for study, commendations) can supplement, but generally cannot fully replace, monetary payments, especially where significant employer profits arise. Their value must be reasonably assessable.

Practical Challenges:

- Calculation Complexity: Performance-based systems can be complex to administer, requiring tracking of sales/profits attributable to specific patents, which can be difficult in products incorporating multiple inventions.

- Contribution Assessment: Determining the relative contributions of the employer (funding, facilities, support staff) and the employee inventor(s) can be subjective.

- Multi-Inventor Issues: Allocating benefits among multiple inventors requires a clear and fair internal process.

Companies should design systems that are transparent, perceived as fair by employees, administratively feasible, and align with the company's overall R&D strategy and culture, while always ensuring the procedural steps outlined in the METI Guidelines are followed.

Scope of Applicability: Who is an "Employee, Etc."?

Article 35 applies broadly to "employees, etc." (jūgyōsha-tō). While regular employees and company officers clearly fall within this scope, the status of non-standard workers raises practical questions.

- Dispatched Workers (Haken Rōdōsha): These workers are employed by a dispatch agency but work under the direction of a client company (the receiving company). If such a worker creates an invention related to the receiving company's business and duties performed there, who is the relevant "employer" for Article 35 purposes? Legal commentary suggests that often the receiving company is considered the relevant employer, based on factors like who provides the R&D facilities and resources, who directs the work leading to the invention, and who bears the business risk. However, the formal employment relationship is with the dispatch agency. To avoid ambiguity, the METI Guidelines recommend that the dispatch agency, the receiving company, and the dispatched worker clarify the handling of potential inventions through contractual agreements (ideally a three-party agreement or at least clear terms between the receiving company and the worker/agency).

- Contractors and Freelancers: Individuals working under service contracts (ukeoi or inin) rather than employment contracts are generally not considered "employees, etc." under Article 35. Their inventions typically belong to them unless the contract explicitly assigns IP rights to the commissioning company. However, the distinction between employment and independent contracting can sometimes be blurred based on the actual working relationship (e.g., degree of control and direction). Clear contractual terms regarding IP ownership are essential when engaging external R&D personnel.

Companies relying on non-standard workforces for R&D need carefully drafted contracts that address invention ownership and compensation specifically, considering the nuances of Article 35's applicability.

Handling Retirees

A common practical challenge under older employee invention systems involved ongoing royalty payments (jisseki hōshōkin) based on the long-term success of patents, often continuing long after the inventor retired. This created administrative burdens for companies in tracking retirees, verifying addresses and bank accounts, and processing potentially small, periodic payments. Furthermore, payments made long after retirement may have limited incentive effect for current R&D efforts.

Recognizing these issues, the post-2016 framework and the METI Guidelines offer more flexibility. As noted in legal commentary, the Guidelines explicitly state that providing benefits does not necessarily require continuous payments after retirement. Companies can structure their systems to provide benefits through lump sums paid during employment, at the time of patent registration, or as a final settlement upon retirement. This approach can significantly reduce administrative burdens and allow companies to focus incentive resources more effectively on current employees, provided the overall benefit determined through fair procedures is considered "reasonable."

Joint Development and Third-Party Collaboration

When R&D is conducted jointly with other companies, universities, or research institutions, careful contractual planning regarding intellectual property is vital. Joint development agreements should clearly address:

- Ownership of inventions arising from the collaboration (sole ownership by one party, joint ownership).

- Responsibility for patent prosecution and maintenance.

- Handling of employee inventions created by each party's personnel during the collaboration. Each party remains responsible for complying with Article 35 regarding its own employee inventors. Contracts should confirm that each party has secured the necessary rights from its employees (either through assignment or initial vesting) and is responsible for providing any required "reasonable benefit" under its internal system.

Failure to address these points clearly can lead to complex disputes over ownership and compensation down the line.

Comparison with Employee Creations under Copyright Law

It is worth briefly noting that Japan's Copyright Act treats works created by employees differently. Under Article 15 of the Copyright Act, if a work is made by an employee on the employer's initiative and in the course of their duties, and is made public under the employer's name (unless stipulated otherwise in a contract or work rules), the authorship is attributed to the employer, and the copyright generally belongs to the employer automatically. Unlike the Patent Act's Article 35, the Copyright Act does not contain a specific provision entitling the employee creator to additional "reasonable benefit" beyond their regular salary for the transfer of copyright ownership in such "work-for-hire" scenarios.

Conclusion: Procedural Fairness is Paramount

Japan's employee invention system, particularly after the 2016 revisions to Patent Act Article 35, aims to strike a balance between incentivizing employee innovation and providing legal certainty for employers regarding IP ownership. The shift towards emphasizing procedural fairness in determining "reasonable benefit" is the most critical aspect for companies to understand and implement.

For US companies with R&D activities in Japan, establishing a clear, well-documented employee invention policy that complies with the procedural requirements outlined in the METI Guidelines – consultation, disclosure, and feedback opportunities – is essential. This involves not only setting up appropriate compensation structures (whether lump-sum, royalty-based, or a hybrid) but also ensuring the processes for creating and applying these structures are transparent and involve employee input. Careful consideration must also be given to handling inventions by non-standard workers and clarifying IP rights in collaborative projects. By proactively developing and fairly implementing a compliant employee invention system, companies can mitigate legal risks, foster a positive environment for innovation, and ensure they secure the rights to valuable intellectual property generated by their workforce in Japan.

- Patent Strategies for Foreign R&D Subsidiaries in Japan

- Trade Secrets vs. Patents: Protecting Know-How in Japanese Joint Ventures

- Japan’s 5-Year Rule for Fixed-Term Contracts: Avoiding Pitfalls for Employers

- METI | Guidelines on Procedures for Reasonable Benefits to Employee Inventors (English summary)

https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2016/0122_02.html - JPO | Outline of Employee Invention System after 2016 Amendment

https://www.jpo.go.jp/e/system/patent/gaiyo/employee-invention.html