Employee Inventions, Global Patents: Japanese Supreme Court on Remuneration for Foreign Patent Rights

Date of Judgment: October 17, 2006

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

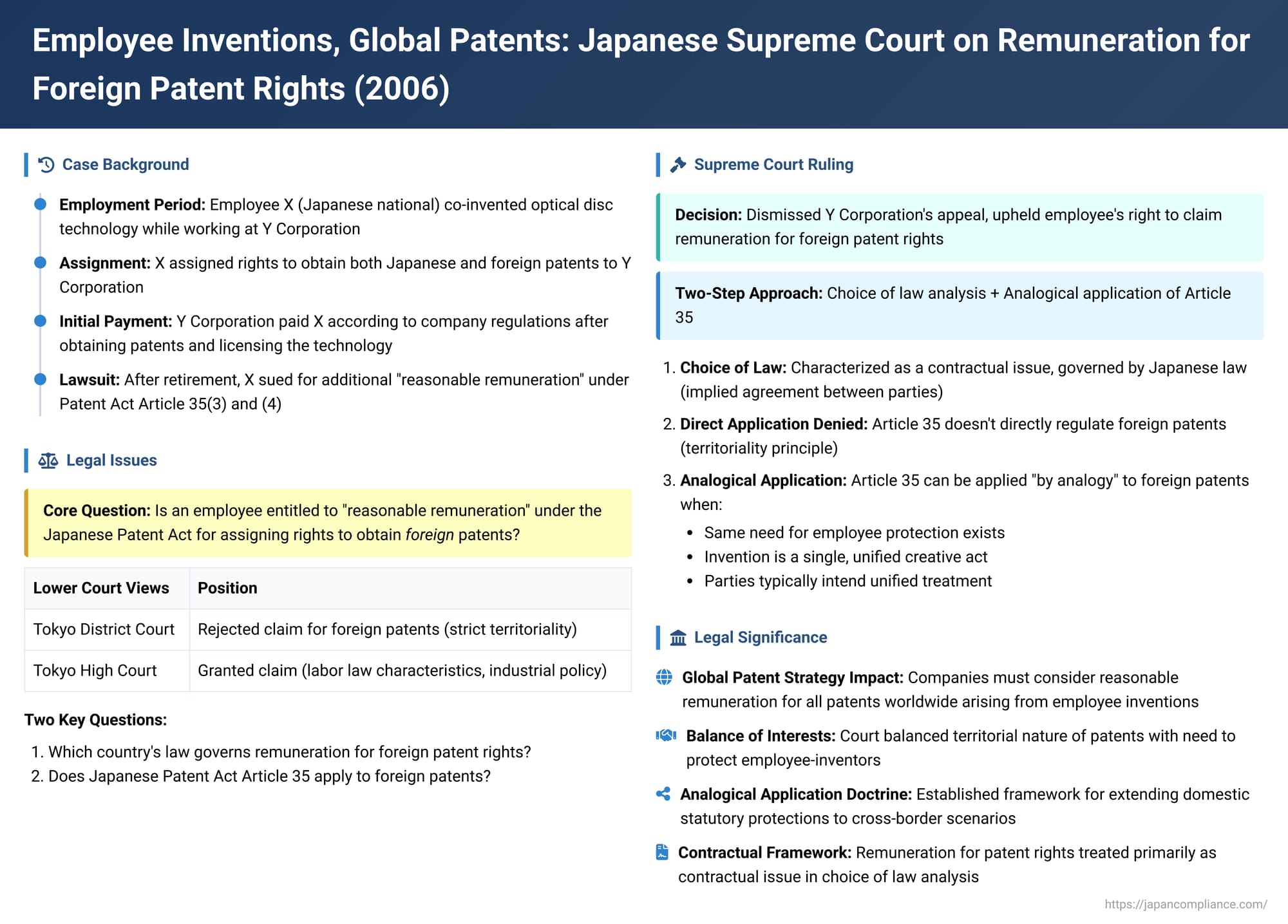

When an employee creates an invention as part of their duties, and that invention leads to valuable patents not just domestically but in multiple countries, complex questions arise regarding fair compensation for the employee. A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision on October 17, 2006, addressed the crucial issue of whether an employee is entitled to "reasonable remuneration" under the Japanese Patent Act for assigning to their employer the rights to obtain foreign patents. This case delves into the intersection of contract law, patent law, and private international law, offering significant guidance on how such cross-border employee invention scenarios are handled.

The Factual Background: An Employee Invention with International Reach

The dispute involved a former employee and their employer, a major Japanese corporation:

- Mr. X (Plaintiff): A Japanese national and former employee of Y Corporation.

- Y Corporation (Defendant): A Japanese electronics manufacturer, Mr. X's former employer.

- The Invention: While employed at Y Corporation, Mr. X, along with other employees, co-invented a significant technology related to optical discs. This was recognized as an "employee invention" (職務発明 - shokumu hatsumei) under the Japanese Patent Act.

- Assignment of Rights: Mr. X and Y Corporation entered into an "Assignment Agreement." Under this agreement, Mr. X assigned to Y Corporation his rights to obtain patents for the invention, covering not only Japan but also foreign countries.

- Profits and Initial Payment: Y Corporation subsequently obtained patents for the invention in Japan and various foreign countries. It licensed this technology to multiple companies, deriving substantial profits. Y Corporation paid Mr. X a certain sum as consideration for the assignment, an amount determined according to its internal company regulations.

- The Lawsuit: After retiring from Y Corporation, Mr. X filed a lawsuit. He argued that the payment he had received was insufficient and claimed "reasonable remuneration" (相当の対価 - sōtō no taika) as stipulated by Article 35, paragraphs 3 and 4 of the Japanese Patent Act (the provisions in effect before the 2004 amendments). Critically, his claim included remuneration for the assignment of rights to obtain foreign patents.

The lower courts had offered differing views. The Tokyo District Court (first instance) rejected the claim concerning foreign patent rights, citing the principle of territoriality in patent law. However, the Tokyo High Court (appellate court) found that Japanese law governed the assignment agreement. It further reasoned that Article 35 of the Patent Act had labor law characteristics and should apply unitarily to remuneration claims, including those for foreign patent rights, based on the industrial policy of the country governing the employment relationship. The High Court thus ruled in favor of Mr. X regarding the foreign patent rights, leading Y Corporation to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Questions Before the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court was faced with two primary questions:

- Which country's law should govern an employee's claim for remuneration arising from the assignment of rights to obtain foreign patents for an employee invention?

- If Japanese law is found to be the governing law, does Article 35 of the Japanese Patent Act, which provides for "reasonable remuneration" to employee-inventors, apply to the assignment of rights to obtain foreign patents?

The Supreme Court's Path to a Solution

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Corporation's appeal, upholding the employee's right to claim remuneration for the foreign patent rights, though its reasoning, particularly concerning the application of Article 35, differed in nuance from the High Court.

1. Choice of Law for Remuneration Claims:

The Supreme Court first addressed the question of which law should govern the employee's claim for remuneration.

- It characterized the issue – whether an assignor (employee) can claim remuneration from an assignee (employer) for transferring the right to obtain a patent, and the amount of that remuneration – as fundamentally a matter of contract law. Specifically, it concerns the contractual rights and obligations arising from the Assignment Agreement between Mr. X and Y Corporation.

- Under Japanese private international law (Article 7(1) of the Horei, the old Act on Application of Laws, now Article 7 of the Act on General Rules for Application of Laws), the governing law for a contract is primarily determined by party autonomy – that is, the law chosen by the parties, whether expressly or implicitly.

- In this particular case, the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's finding that there was an implied agreement between Mr. X and Y Corporation that Japanese law would govern their Assignment Agreement, including issues related to remuneration for the assigned patent rights.

2. Applicability of Japanese Patent Act Article 35 to Foreign Patent Rights:

Having established Japanese law as the governing law for the remuneration issue, the Supreme Court then considered whether Article 35, paragraphs 3 and 4, of the Japanese Patent Act could be applied to the assignment of rights to obtain foreign patents.

- Direct Application Denied:

The Court stated that the Japanese Patent Act, by its nature, does not directly regulate foreign patents or the rights to obtain foreign patents. This is consistent with the principle of territoriality, where patent rights are generally confined to the jurisdiction that grants them.

The Court noted that terms like "the right to obtain a patent" in other parts of Article 35 (specifically paragraphs 1 and 2, which deal with the employer's presumptive right to a non-exclusive license or to succeed to the invention) must be interpreted as referring to the right to obtain a Japanese patent.

Given this context, the Supreme Court found it textually difficult to interpret only paragraph 3 of Article 35 (which establishes the employee's right to "reasonable remuneration") as encompassing the right to obtain foreign patents when other parts of the same article are limited to Japanese rights.

Therefore, the Court concluded that direct application of Article 35(3) and (4) to claims for remuneration for assigning the right to obtain foreign patents was not possible. - Analogical Application Affirmed:

Despite denying direct application, the Supreme Court found compelling reasons to apply Article 35(3) and (4) by analogy (類推適用 - ruisui tekiyō) to the assignment of rights to obtain foreign patents. Its reasoning was as follows:- Purpose of Employee Protection: The core purpose of Article 35(3) and (4) is to protect employee-inventors. These provisions recognize that employees are often in an unequal bargaining position when assigning valuable invention rights to their employers. The law aims to ensure that employees receive a fair share of the benefits the employer derives from exploiting the invention, thereby providing an incentive for invention and contributing to overall industrial development.

- Identical Need for Protection: This imbalance in bargaining power and the consequent need for employee protection are identical whether the rights being assigned pertain to Japanese patents or to foreign patents.

- Unified Nature of the Invention: Although patent rights are granted on a country-by-country basis, they frequently originate from a single, underlying inventive concept or act. In the context of employee inventions, it is the common understanding and usual intention of the parties (employee and employer) to deal with the legal relationship concerning that single underlying invention in a comprehensive and unified manner, encompassing all potential patent rights that may arise from it globally.

- Extending the Spirit of the Law: Given these factors, the Court found that a situation exists where the spirit and purpose of Article 35(3) and (4) should indeed extend to the assignment of rights to obtain foreign patents.

- The Supreme Court thus concluded that when an employee assigns to their employer the right to obtain a foreign patent for an invention qualifying as an employee invention under Article 35(1), the provisions of Article 35(3) and (4) of the Japanese Patent Act should be applied by analogy to the employee's claim for remuneration for such an assignment.

Outcome and Significance

The Supreme Court's decision meant that Mr. X was entitled to claim reasonable remuneration from Y Corporation not only for the assignment of the right to the Japanese patent but also, by analogy, for the assignment of the rights to obtain patents in foreign countries. The case was a significant victory for employee-inventors in Japan.

This judgment is important for several reasons:

- Clarity on Choice of Law: It clarified that disputes over remuneration for assigning foreign patent rights arising from employee inventions are, in the first instance, contractual matters. The governing law is determined by the choice of law rules applicable to contracts (party autonomy).

- Analogical Application of Patent Act Art. 35: The decision to apply Article 35 of the Japanese Patent Act by analogy to rights to obtain foreign patents (when Japanese law governs the assignment) was a landmark step. It recognized the protective intent of the statute and the practical realities of global patenting for inventions made by employees.

- Rejection of Strict Territoriality for Remuneration Claims: While acknowledging the territorial nature of patent rights themselves, the Court did not allow this principle to prevent a claim for fair remuneration under the chosen Japanese governing law, even if that remuneration was linked to foreign patent potential. The trial court had initially taken a stricter view based on territoriality.

- Alternative Choice-of-Law Theories: Academic commentary notes that other theories for determining the governing law exist, such as applying the law of the country where the patent is registered or the law governing the employment relationship itself. The Supreme Court, in this instance, opted for the contractual approach for the remuneration claim.

- Impact of Subsequent Legal Changes: Professor Yokoyama's commentary points out that this decision was made under the old Horei. The current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws now contains specific protective choice-of-law rules for employment contracts (Article 12), which might allow the law of the place of work to govern remuneration issues for ordinary employees more directly in some cases today. Furthermore, amendments to the Japanese Patent Act itself (in 2004 and 2015, changing "reasonable remuneration" to "reasonable benefit" and detailing procedures for its determination) have occurred. It is likely that the principles underlying these newer provisions would also be considered applicable by analogy in similar cases involving foreign patent rights.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2006 decision in this employee invention case is a critical ruling that balances the principles of contractual freedom with the need to protect employee-inventors in an increasingly internationalized innovation landscape. By confirming that Japanese law, if chosen to govern the assignment, allows for claims of reasonable remuneration for foreign patent rights through the analogical application of its domestic Patent Act, the Court reinforced Japan's commitment to ensuring that inventors receive a fair share of the rewards generated by their creations, regardless of where those creations are ultimately patented and exploited. This judgment continues to be a vital reference point for employee-employer relations concerning intellectual property in Japan.