Emergency Care, Patient Rights, and Public Interest: Japan's Supreme Court on Doctor's Drug Testing and Police Reporting

Decision Date: July 19, 2005, Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench (Heisei 17 (A) No. 202)

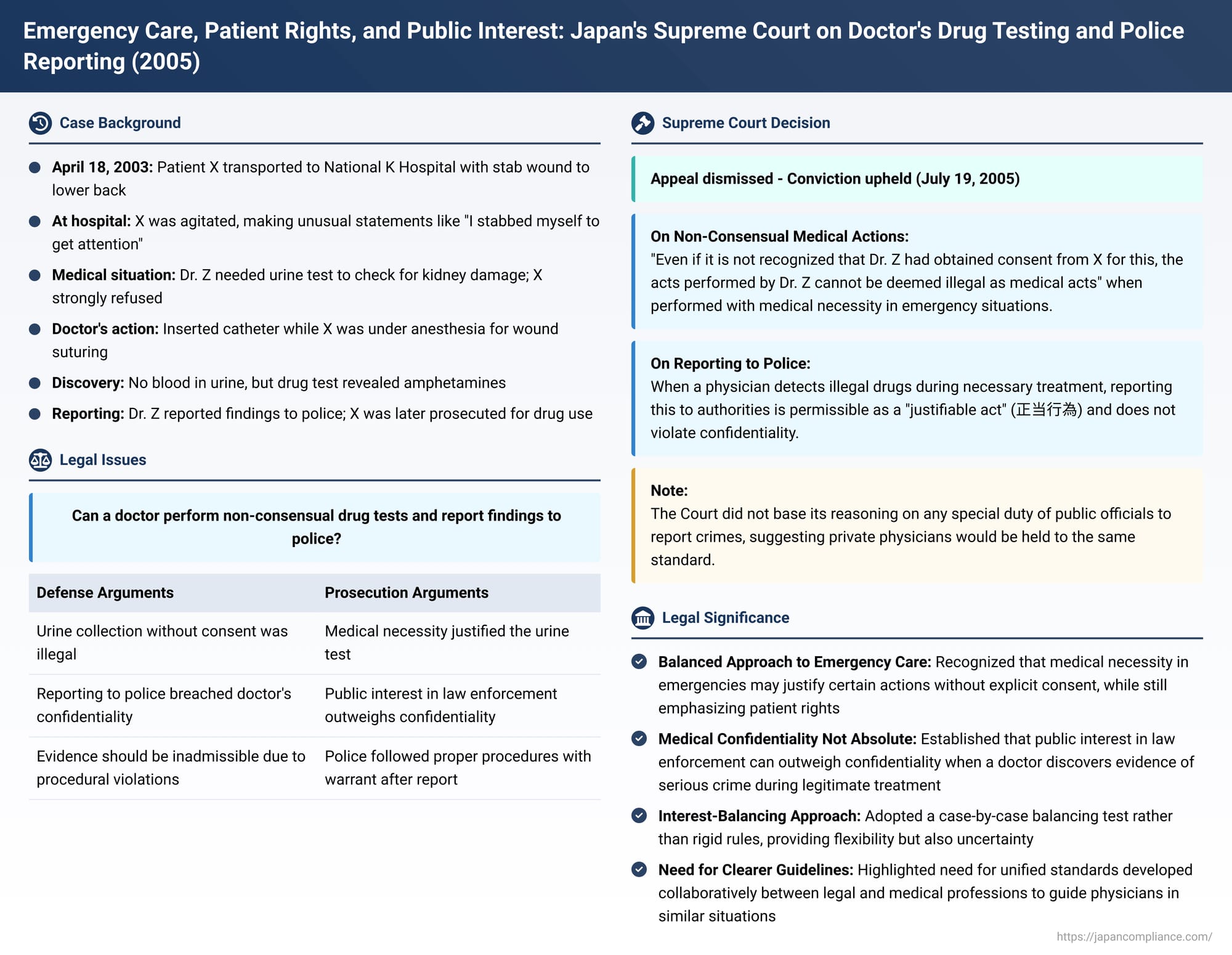

In a pivotal decision issued on July 19, 2005, Japan's Supreme Court addressed complex legal and ethical questions arising when emergency medical treatment intersects with suspected criminal activity. The case involved a patient who underwent a non-consensual urine test that detected illegal drugs, leading to a police report by the treating physician. The Court's ruling provides crucial insights into the balance between a patient's rights, a doctor's medical judgment in emergencies, the duty of confidentiality, and the public interest in law enforcement.

The Emergency Room Incident

The defendant, identified as X, was transported to National K Hospital in Tokyo via ambulance after sustaining a stab wound to the right lower back during a dispute with a cohabiting partner. This occurred on April 18, 2003, after X had received initial emergency treatment at another facility for significant blood loss. Upon arrival at National K Hospital around 8:30 PM, X was conscious and lucid but agitated, making statements such as, "It doesn't hurt, let me go home," and, "I stabbed myself to get his attention, but in the end, everyone's ignoring me". The attending physician, Dr. Z, observed a stab wound approximately 3 cm in length on X's right lower back, with a large amount of blood on X's clothing.

Disputed Medical Procedures

Dr. Z determined that a urine test was necessary to ascertain whether the stab wound had reached X's kidney, as this would invariably result in hematuria (blood in the urine). When Dr. Z explained the need for the urine test, X strongly refused. After conducting CT scans and other imaging diagnostics, which showed air near the kidney but no immediate signs of intra-abdominal bleeding (though acute-stage bleeding could not be ruled out), Dr. Z remained convinced that a urine sample was essential. Despite X's continued objections over a period of about 30 minutes, Dr. Z ultimately informed X that anesthesia would be administered to suture the wound to stop the bleeding, and that a urinary catheter would be inserted during this procedure. X did not object to this and received the anesthetic injection.

While X was under anesthesia, Dr. Z performed the suturing operation and inserted a catheter to collect a urine sample. Although the urine showed no signs of blood, Dr. Z, considering X's agitated state and statements about self-stabbing, suspected potential drug influence. A simple drug test was performed on the urine sample, which yielded a positive reaction for amphetamines.

From Medical Finding to Criminal Investigation

Subsequently, Dr. Z met with X's parents, who had arrived at the hospital. Dr. Z explained X's condition and informed them that X's urine had tested positive for stimulants. Dr. Z also stated that, as a national public servant (physicians at National K Hospital, a state-run institution at the time, were generally considered public officials), there was an obligation to report this finding to the police. X's parents appeared to ultimately consent to this course of action. Dr. Z then reported the positive amphetamine result from X's urine to an officer at the Metropolitan Police Department's Tamagawa Police Station.

On April 21, officers from the Tamagawa Police Station obtained a search and seizure warrant. Based on this warrant, they seized the urine sample collected by Dr. Z. This sample was sent to a forensic science laboratory for analysis, resulting in an official report confirming the presence of amphetamine components.

The Legal Challenge: Admissibility of Evidence

X was subsequently prosecuted for self-use of stimulants, a violation of the Stimulant Control Law. The defense argued that the urine sample and the resulting forensic report should be inadmissible as evidence. The core arguments were:

- The urine collection and drug test lacked true medical necessity and were performed without X's valid consent, rendering them illegal medical acts.

- Dr. Z's report to the police constituted a breach of the physician's duty of confidentiality.

- The police effectively exploited Dr. Z's allegedly illegal actions to obtain the urine, thereby violating the spirit of the warrant principle and constituting a serious procedural illegality.

Despite these arguments, X was convicted in the first instance, and this judgment was upheld by the appellate court, leading to the appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (July 19, 2005)

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court's First Petty Bench dismissed X's appeal and upheld the conviction. The Court addressed the legality of both the doctor's actions and the subsequent police investigation.

1. Legality of the Medical Actions (Urine Collection and Drug Test):

The Court found that, under the circumstances, Dr. Z collected the urine sample and conducted the drug test for the purpose of treating an emergency patient. It recognized that these actions had medical necessity. Crucially, the Court stated that "even if it is not recognized that Dr. Z had obtained consent from X for this, the aforementioned acts performed by Dr. Z cannot be deemed illegal as medical acts". This suggests that in emergency situations with clear medical necessity, the absence of explicit, contemporaneous consent for every specific diagnostic step might not render the medical action illegal.

2. Legality of Reporting to Police:

Regarding the disclosure of the positive drug test to the police, the Supreme Court held that when a physician, in the course of necessary treatment or examination of a patient, detects components of an illegal drug in the patient's urine, reporting this to investigative authorities is permissible as a "justifiable act" (正当行為 - seito koi). Such reporting, the Court concluded, does not violate the physician's duty of confidentiality.

3. Admissibility of Evidence:

Based on these findings, the Court determined that there was no illegality in the process by which the police obtained X's urine sample. Therefore, the arguments asserting the inadmissibility of the urine analysis report and related evidence, which were predicated on the alleged illegality of Dr. Z's actions, lacked foundation. The lower courts' decisions to admit this evidence were deemed correct.

Key Issues and Commentary

This Supreme Court decision was groundbreaking as it was the first time the Court had ruled on two critical issues: (1) the legality of drug testing by a physician without explicit patient consent in certain medical contexts, and (2) the relationship between a physician's duty of confidentiality and the act of reporting a patient's suspected crime discovered during medical care.

On Non-Consensual Drug Testing:

Patient self-determination is a cornerstone of medical ethics, generally requiring informed consent for all treatments and tests. However, medical practice, especially in emergencies, often involves evolving diagnostic and treatment pathways where consent might be somewhat general or implied by the circumstances.

Legal commentary on this case notes the Supreme Court's apparent reluctance to definitively state that X had consented to the drug test, given the phrasing "even if it is not recognized that consent was obtained". The drug test itself, unlike a test for blood in the urine (which X initially refused for any urine test), was not directly aimed at diagnosing kidney injury related to the stab wound, but rather stemmed from X's behavior. This has led some scholars to suggest the Court justified the drug test based on the "objective benefit" to the patient, even if it went against X's expressed wishes, particularly if the drug use posed risks that the patient might not fully appreciate.

However, the commentary also points out that X was conscious and lucid, and there was no concrete evidence presented of an ongoing, immediate danger of self-harm or harm to others beyond the general risks abstractly associated with drug use. The decision, therefore, appears to accept a more generalized risk as sufficient to override the patient's refusal in the context of emergency treatment, a point on which legal opinions are divided.

On Doctor's Confidentiality vs. Reporting Patient's Crime:

A physician's duty to maintain patient confidentiality is a fundamental ethical principle, also protected under Japanese criminal law (Article 134 of the Penal Code, which criminalizes the unauthorized disclosure of secrets learned in a professional capacity). Information about a patient committing a crime is generally considered a protected secret.

In this case, Dr. Z (a national public servant at the time) had mentioned to X's parents a perceived duty to report the crime under Article 239, Paragraph 2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (which mandates public officials to report crimes they become aware of in the course of their duties). The lower courts had cited this as a basis for finding no breach of confidentiality.

Significantly, the Supreme Court's ruling did not reference this statutory duty for public officials when it concluded that reporting was permissible. Legal commentators widely interpret this omission as the Court deliberately choosing not to differentiate between physicians in the public sector and those in private practice regarding this issue. This implies that the Court does not necessarily endorse a general, overriding duty for physicians (even public ones) to report all patient crimes to prosecutorial authorities.

If the only active legal duty in such a scenario is the duty of confidentiality, then logically, reporting might seem impermissible. The Supreme Court's rationale that reporting was a "justifiable act" is thus understood by many commentators as an act of balancing competing interests: the public interest in the investigation and prosecution of crime versus the patient's individual interest in the confidentiality of their medical information, with the public interest prevailing under these specific circumstances.

This "balancing of interests" approach, while offering flexibility, has been critiqued for its lack of clear, advance guidance for physicians. Doctors face a wide spectrum of situations, from minor offenses confessed by patients to serious, unsolved crimes, and deciding where the balance tips can be fraught with uncertainty. An incorrect judgment could theoretically expose a physician to criminal liability for breach of confidentiality or civil liability, even if active prosecution by authorities is rare.

Traditional Legal Framework and Its Limits:

Historically, Japanese legal scholarship often argued that physicians cooperating with criminal justice investigations would not be held liable for breaching confidentiality. The Code of Criminal Procedure (Articles 105 and 149) grants physicians the right to refuse to produce evidence or testify about patient secrets learned "due to professional entrustment". The prevailing view was that exercising this right was at the physician's discretion, and choosing to cooperate with law enforcement would negate the illegality of disclosure. This was often justified by reasoning that the right of refusal primarily served to protect societal trust in the medical profession rather than solely individual patient privacy; thus, if a physician judged that cooperation was necessary to maintain that trust (e.g., by not appearing to conceal crimes), their decision was respected.

The commentary in the provided source suggests that this traditional view, which effectively gives physicians broad discretion, may not align well with contemporary legal sensibilities that place greater emphasis on individual patient rights and privacy. The Supreme Court's decision in this case, by not explicitly adopting this older rationale, is seen as a prudent move.

The Path Forward: Seeking Unified Standards:

The commentary suggests that instead of relying on case-by-case interest balancing or overly rigid rules, a more constructive approach would involve collaboration between the legal and medical professions to develop unified standards or guidelines. Such guidelines could help physicians navigate these difficult situations with greater clarity. If a physician, acting in good faith and adherence to such established standards, chooses to cooperate with criminal justice authorities, they should ideally be shielded from both criminal and civil liability for breach of confidentiality. This approach acknowledges that while the primary legal obligation remains confidentiality, there may be specific, well-defined circumstances where reporting is ethically and legally justifiable in the broader public interest. If society deems reporting obligatory in certain scenarios (e.g., child abuse, as already legislated), then specific laws should mandate it.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2005 decision in this case remains a significant reference point for understanding the legal boundaries of medical practice in Japan, especially in emergency situations involving patients suspected of criminal offenses. It affirms that medical necessity can, in limited emergency contexts, permit actions taken without full contemporaneous consent, and that a physician's duty of confidentiality is not absolute when faced with evidence of serious illegal activity discovered during legitimate medical care. The ruling underscores the ongoing dialogue needed to provide clear, ethically sound, and legally robust guidance for medical professionals navigating these challenging intersections of patient care, individual rights, and public safety.