Embezzlement or Breach of Trust? A Foundational Japanese Ruling on Corporate Misconduct

An executive is entrusted with company funds. A close friend, whose own business is on the brink of collapse, pleads for a loan from the company's coffers. The executive, acting not for direct personal financial gain but out of a misplaced sense of loyalty to their friend, makes an unauthorized loan of company money to the friend's struggling business, putting the company's assets at risk. Has this executive committed embezzlement, the crime of treating the company's money as their own? Or have they committed breach of trust, the crime of disloyally managing the company's affairs to its detriment?

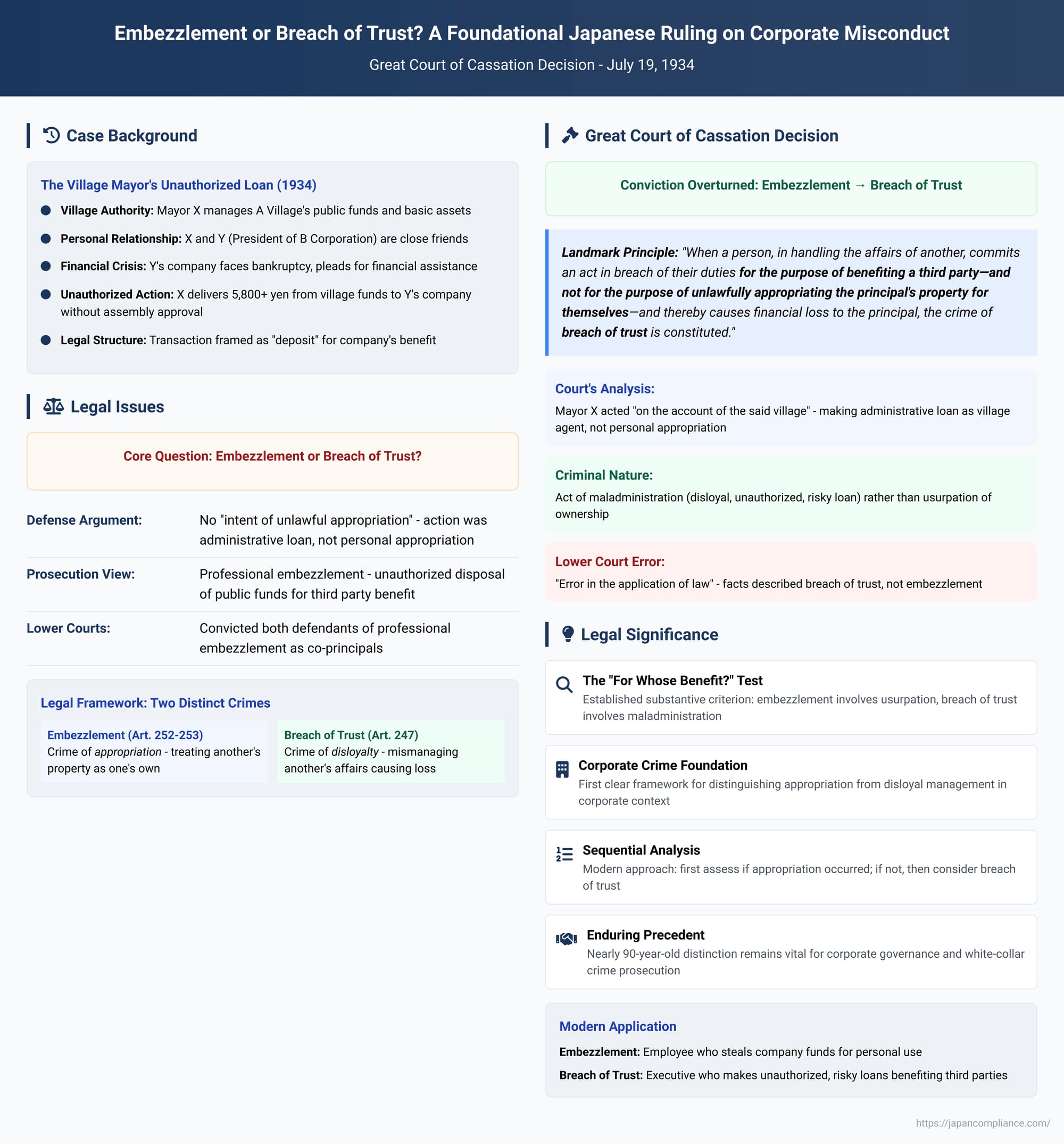

This crucial distinction, which lies at the heart of corporate criminal law, was the subject of a foundational ruling by Japan's Great Court of Cassation (the predecessor to the modern Supreme Court) on July 19, 1934. The case, involving a village mayor who made an illicit loan from public funds to a friend's company, was the first to clearly articulate the legal line between an act of appropriation and an act of betrayal, a distinction that remains vital today.

The Facts: The Village Mayor and the Failing Company

The defendant, X, was the mayor of A Village. He was a close personal friend of Y, the president of a company called B Corporation. Y's company was facing financial ruin, and he implored Mayor X to lend him money from the village's basic assets, which X managed as part of his official duties as mayor.

X agreed. On two occasions, without obtaining the legally required approval of the village assembly, he delivered a total of over 5,800 yen—a significant sum at the time—from the village's funds to Y. The transaction was structured as a "deposit" made for the benefit of Y's company.

The lower courts convicted both Mayor X and the company president Y of professional embezzlement (gyōmu-jō ōryō) as co-principals. The defense appealed, arguing that Mayor X lacked the "intent of unlawful appropriation" (fusei ryōtoku no hani) necessary for embezzlement. They contended that his wrongful act, at most, constituted the separate and distinct crime of breach of trust (hainin-zai).

The Legal Framework: Embezzlement vs. Breach of Trust

The defense's argument highlighted a critical area of overlap in property crime law. Both embezzlement and breach of trust involve a person in a position of trust causing financial harm to a principal or beneficiary. However, they are distinct crimes.

- Embezzlement (Article 252 & 253 of the Penal Code): This is fundamentally a crime of appropriation. It involves a person who is in lawful possession of another's property (a trustee) unlawfully treating that property as if it were their own, either for their own benefit or for a third party's. The core concept is the usurpation of the owner's rights.

- Breach of Trust (Article 247): This is a crime of disloyalty. It involves a person who is tasked with managing another's affairs acting contrary to their duties for the purpose of benefiting themselves or a third party, thereby causing financial loss to the principal. The core concept is an act of maladministration that betrays the trust placed in the agent.

In many situations, an act can appear to fit both descriptions. Japanese law has traditionally held that embezzlement is the more serious, specific crime, and that breach of trust applies only when the elements of embezzlement are not met. Therefore, distinguishing between them is crucial.

The Court's Landmark Ruling: A Crime of Betrayal, Not Usurpation

The Great Court of Cassation agreed with the defense's legal argument. In a landmark decision, it overturned the embezzlement conviction and found the defendants guilty of breach of trust instead.

The Court laid out a clear principle for distinguishing the two crimes:

"When a person, in handling the affairs of another, commits an act in breach of their duties for the purpose of benefiting a third party—and not for the purpose of unlawfully appropriating the principal's property for themselves—and thereby causes financial loss to the principal, the crime of breach of trust is constituted, and this should not be charged as the crime of embezzlement."

Applying this principle to the facts, the Court found that Mayor X did not take the village's money for himself. Rather, he made a loan from the village to Y's company. He was acting, albeit improperly, "on the account of the said village". He was performing an administrative act (making a loan) as the village's agent. His crime was that this act was disloyal (it benefited his friend at the village's expense) and a breach of his duty (it lacked the required assembly approval). This was a quintessential act of maladministration, not an act of personal appropriation. The facts, the Court concluded, described a breach of trust, and the lower court had committed an "error in the application of law" by convicting for embezzlement.

Analysis: The "For Whose Benefit?" Test

This 1934 decision established what can be called the "for whose benefit?" or "on whose account?" test. It provides a substantive way to distinguish the two crimes by looking at the economic reality of the transaction.

- Embezzlement involves an act of usurpation. The perpetrator effectively takes the property out of the principal's sphere of control and treats it as their own. The money is no longer being used "on the principal's account."

- Breach of Trust involves an act of maladministration. The perpetrator is still acting in their capacity as an agent for the principal, but they are doing so disloyally and harmfully. The loan made by Mayor X was still legally a "village loan," just an unauthorized, improper, and risky one made for the benefit of a third party.

Modern legal scholarship generally supports this distinction, framing it as a sequential analysis: First, a court should ask if the facts constitute an appropriation of property. If they do, the crime is embezzlement. If, and only if, the act does not rise to the level of appropriation, the court should then ask if it constitutes a disloyal breach of duty causing loss. This 1934 ruling is seen as an early and foundational application of this substantive and logical approach.

Conclusion: The Enduring Line Between Two Corporate Crimes

The 1934 decision of the Great Court of Cassation remains a cornerstone of Japanese white-collar criminal law. It provided the first clear judicial framework for distinguishing the crime of embezzlement from the crime of breach of trust. The key distinction lies not in the financial outcome, which may be identical, but in the fundamental nature of the defendant's act.

Embezzlement is a crime of usurpation, where the agent steps into the shoes of the owner and treats the property as their own. Breach of trust is a crime of maladministration, where the agent, while acting in their official capacity, does so in a manner that is disloyal and harmful to the principal they are supposed to serve. This nearly century-old ruling remains essential for corporate governance, providing a clear line between the employee who steals from the company and the one who, while still acting criminally, merely manages the company's affairs in a profoundly disloyal manner.