Effect of Wage Garnishment After Resignation and Rehire: A 1980 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Case Name: Claim for Collection of Attached Claim

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 54 (O) No. 789

Date of Judgment: January 18, 1980

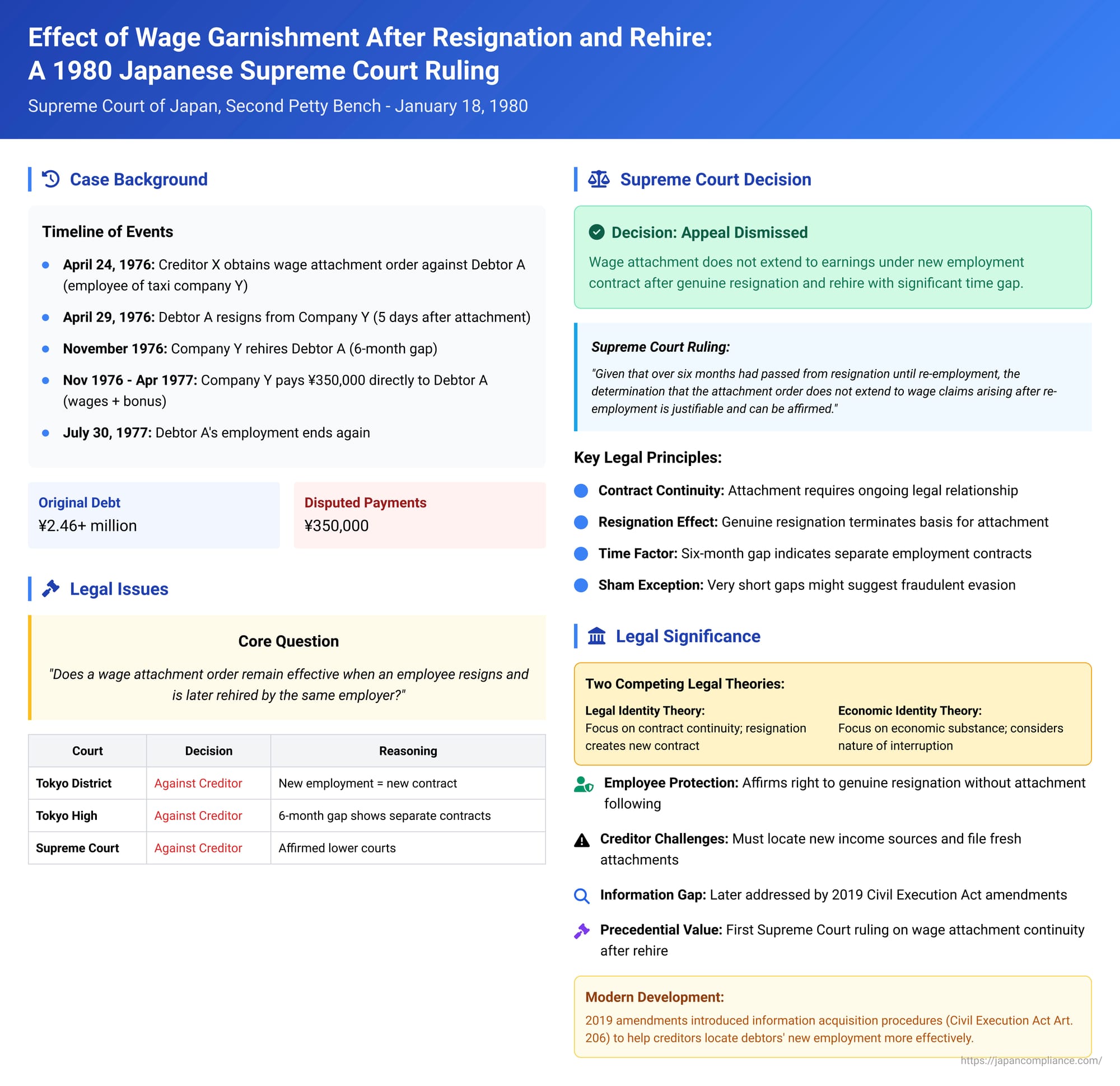

This article examines a Japanese Supreme Court judgment from January 18, 1980, which addressed the enduring effect of a wage garnishment order when an employee resigns and is subsequently rehired by the same employer after a period of interruption. This decision is crucial for understanding the scope and limitations of attaching "claims for continuous performance," such as salary, in Japan.

Factual Background: Attachment, Resignation, Rehire, and Disputed Payments

The case involved the following sequence of events:

- Initial Debt and Wage Attachment:

- Creditor X held an enforceable monetary claim exceeding JPY 2.46 million against Debtor A.

- Debtor A was employed by Company Y, a taxi company.

- Creditor X obtained an attachment and collection order (saiken sashiosae・toritate meirei) for Debtor A's wage claims (salary, bonuses, etc., from April 1976 onwards) against Company Y. This order was served on Company Y on April 24, 1976.

- Debtor's Resignation and Subsequent Payments by Employer:

- Despite the attachment order, Company Y paid Debtor A a total of JPY 350,000. This sum comprised wages for the period November 1976 to April 1977, and a winter bonus for December 1976.

- Company Y's defense for making these payments directly to Debtor A (instead of to the attaching creditor X) was that Debtor A had resigned from his employment on April 29, 1976—just five days after the attachment order was served. Company Y argued this resignation rendered the attachment order ineffective for any subsequent earnings.

- Debtor's Re-employment:

- Company Y further stated that it had newly hired Debtor A in November 1976 (approximately six months after his resignation) and continued to employ him until July 30, 1977. Company Y contended that the original attachment order, issued before the resignation, did not extend to wage claims arising under this new employment contract.

- Creditor's Lawsuit:

- Creditor X sued Company Y (the employer and third-party debtor) for JPY 350,000 in damages, alleging that Company Y's direct payments to Debtor A, in defiance of the attachment order, had caused X to suffer losses.

The Core Legal Question

The central legal issue was whether a wage attachment order obtained before an employee's resignation remains effective against wages earned if that employee is later rehired by the same employer, especially after a significant intervening period without employment.

Lower Courts' Reasoning

- Tokyo District Court (First Instance): The District Court dismissed Creditor X's claim. It held that an employment contract entered into after a resignation is an entirely new legal relationship. Therefore, an attachment order based on the previous contract would not apply to wages from the new contract. The court acknowledged an exception if the resignation was a "sham" (kasō) intended to evade the attachment (which might be presumed if the interruption in employment was very short). However, in this case, with a six-month gap, this presumption did not apply, and there was no other evidence to prove the resignation was a sham.

- Tokyo High Court (Appellate Court): The High Court affirmed the District Court's dismissal. It added that, considering the time interval of over six months between the resignation and re-employment, among other factors, the employment contract that formed the basis of the initially attached wages (prior to April 1976) was different from the contract underlying the wages paid from November 1976 onwards.

Creditor X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the nature of the debt (wages) was identical before and after re-employment, so the attachment should extend. X also contended that a six-month gap was not excessively long (considering unemployment benefit periods, for instance) and that a sham resignation should still be presumed.

The Supreme Court's Decision

On January 18, 1980, the Supreme Court dismissed Creditor X's appeal.

The Court's reasoning was concise, largely affirming the High Court's findings:

"Given the facts legitimately established by the court below, including that over six months had passed from when [Debtor A] resigned from [Company Y] until he was re-employed by [Company Y], the determination by the court below that the effect of the attachment and collection order for wage claims, obtained by the appellant against [Company Y] with [Debtor A] as the debtor before [Debtor A's] resignation, does not extend to wage claims arising after the re-employment, is justifiable and can be affirmed. There is no illegality in the process as alleged by the appellant."

Analysis and Significance

This 1980 Supreme Court decision, though brief, was the first by the highest court to address the effect of wage garnishment after a debtor's resignation and subsequent rehire by the same employer. Its implications are understood in the context of Japanese civil execution law concerning "claims for continuous performance."

- Attachment of "Claims for Continuous Performance":

Article 151 of the Japanese Civil Execution Act (and its predecessor, Article 604 of the old Code of Civil Procedure, relevant at the time of this case) provides that an attachment of "salary or other claims for continuous performance" extends to payments that become due after the attachment. This rule obviates the need for creditors to make repeated attachment applications for each future installment (e.g., each month's salary) and helps prevent debtors from evading execution by disposing of income as soon as it materializes. The effectiveness of this continuous attachment hinges on the persistence of the underlying legal relationship that generates the income, such as an employment contract. - Effect of Resignation on Attachment:

When an employee resigns, the underlying employment contract—the basis for the continuous wage claim—is terminated. Generally, this means the wage attachment order loses its effect for any earnings that would have accrued after the termination. The law does not prevent an employee from resigning even if their wages are attached and even if the resignation might disadvantage the attaching creditor. - Theories on Re-employment and Attachment Revival: The core debate when an employee is rehired by the same employer centers on whether the old attachment order can "revive" or extend to the new employment contract. Two main theories have been discussed by legal scholars:

- Legal Identity Theory (hōritsuteki dōitsusei setsu): This theory, which appeared to underpin the lower court decisions affirmed by the Supreme Court in this case, focuses on the legal continuity of the employment contract. A resignation typically severs this continuity, and a subsequent rehire creates a new, distinct contract. Under this view, the prior attachment order would not apply to the new contract unless the resignation and rehire were a "sham" designed to fraudulently evade the attachment. A very short interval between resignation and rehire might lead to a factual presumption of such a sham, but a more extended period, like the six months in this case, would generally indicate two separate contracts.

- Economic Identity Theory (keizaiteki dōitsusei setsu): This theory places less emphasis on the formal legal contracts and more on the economic substance and continuity of the employment relationship. It asks whether the termination was truly "final" or merely "provisional" (e.g., as might occur with seasonal workers who are regularly laid off and rehired). Under this view, the length of the interruption is not the sole determinant; the expectation of re-employment and the nature of the work are also key.

- Supreme Court's Stance: By affirming the High Court's decision, which emphasized the time gap and the distinctness of the employment contracts, the Supreme Court in this 1980 case effectively endorsed an outcome consistent with the Legal Identity Theory, at least for situations involving a substantial interruption like six months. It did not explicitly adopt a specific theory but found the lower court's conclusion justifiable on the facts.

- Challenges for Creditors: This ruling highlights the significant challenge creditors face when a debtor whose wages are garnished resigns. If the resignation is genuine and not immediately followed by re-employment under circumstances suggesting a sham, the creditor typically needs to undertake new efforts to locate the debtor's new sources of income and, if necessary, initiate a new attachment process. Proving a resignation was a "sham" can be difficult.

- Subsequent Legal Developments (Information Acquisition): Recognizing the difficulties creditors face in tracking debtors' assets and income, Japan amended its Civil Execution Act in 2019. These amendments (e.g., Article 206 of the revised Act) introduced new procedures allowing creditors, particularly those with claims related to support obligations or damages for loss of life or personal injury, to obtain information from third parties (like municipalities or pension administrators) regarding a debtor's sources of income, including employment details. While these reforms don't directly change the principles of attachment continuity discussed in the 1980 case, they provide creditors with better tools to locate a debtor's new employment (whether with the same or a different employer) and potentially file a fresh attachment order more effectively.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1980 decision clarifies that a wage attachment order generally does not extend to wages earned under a new employment contract if the debtor genuinely resigns and is then rehired by the same employer after a significant period (in this case, over six months). The ruling underscores that the continuity of the underlying legal relationship (the employment contract) is essential for the ongoing effect of such an attachment. While this poses challenges for creditors, subsequent legislative reforms have aimed to improve their ability to obtain information about debtors' income sources, potentially mitigating some of these difficulties in practice.