Drug Safety and State Responsibility: Japan's Supreme Court on the Chloroquine Retinopathy Tragedy

Judgment Date: June 23, 1995

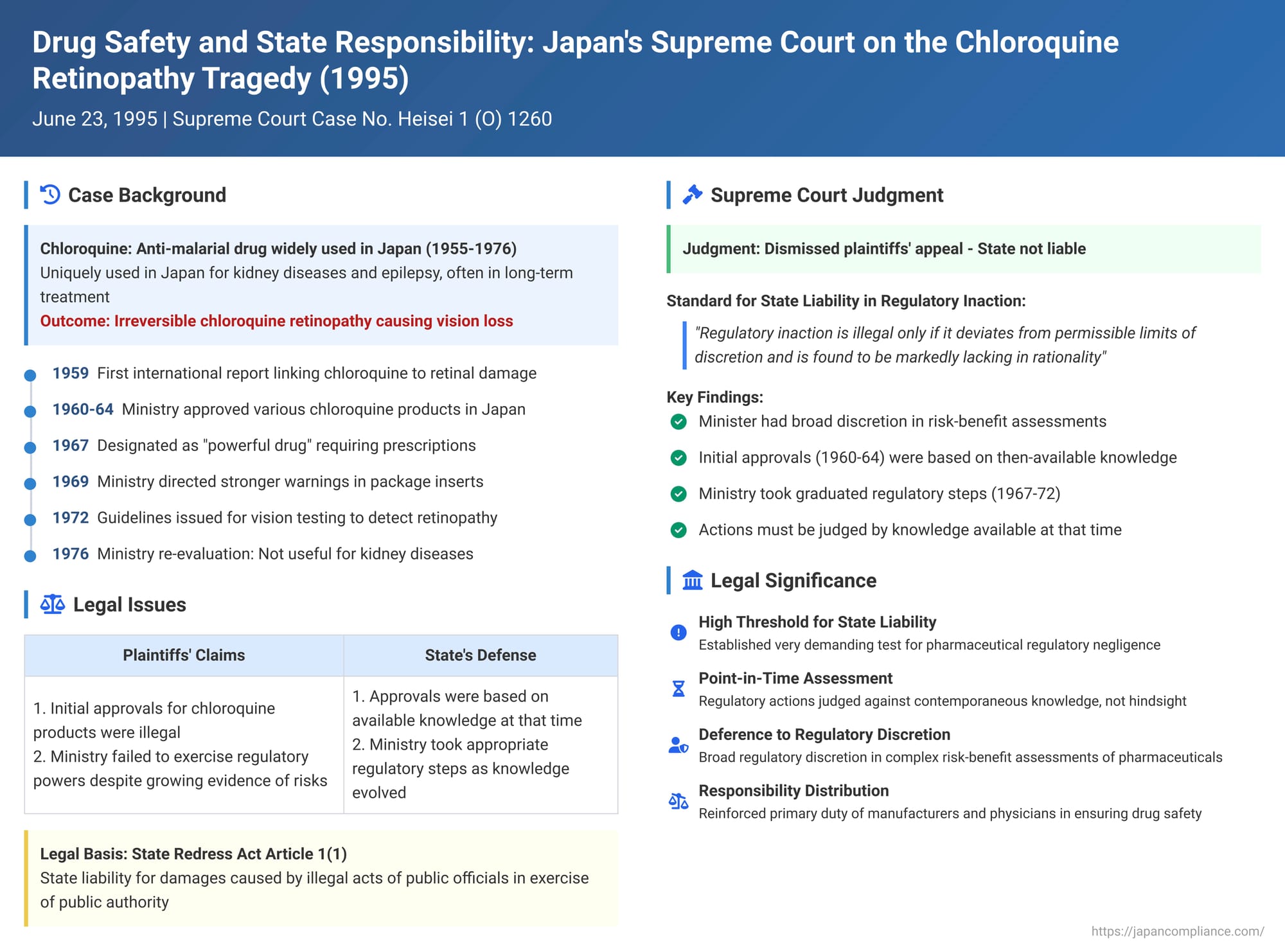

The development and use of pharmaceuticals represent a double-edged sword: while offering cures and relief for many ailments, they also carry the inherent risk of adverse side effects. When such side effects cause widespread harm, questions inevitably arise about the responsibility of not only the drug manufacturers but also the state regulatory bodies tasked with ensuring drug safety. The "Chloroquine Litigation" in Japan was a landmark series of cases culminating in a Supreme Court judgment on June 23, 1995 (Heisei 1 (O) No. 1260), which extensively examined the scope of the State's liability for damages caused by the severe side effects of the drug chloroquine.

Chloroquine: From Anti-Malarial to Widespread Use and a Devastating Side Effect

Chloroquine, a synthetic chemical compound first developed in Germany in 1934 as a treatment for malaria, later found applications in managing other conditions such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. In Japan, chloroquine-based drugs began to be imported, manufactured, and sold around 1955. Notably, and in contrast to practices in many other countries, chloroquine in Japan was also utilized for the treatment of kidney diseases (like nephritis and nephrosis) and epilepsy. This often led to prolonged periods of administration and, in some cases, high dosages.

The tragic consequence of this widespread and sometimes long-term use was the emergence of chloroquine retinopathy, a serious and irreversible degenerative eye disorder caused by the drug's side effects. This condition primarily affects the retina, leading to symptoms such as a narrowing of the visual field and, in severe instances, can progress to blindness. At the time of these events, the precise mechanism of chloroquine retinopathy was not fully understood, and no effective treatment was known.

The plaintiffs in this litigation (X et al.) were patients who developed chloroquine retinopathy, or the families of deceased patients, after being prescribed and taking various chloroquine preparations between 1959 and 1975 for conditions including kidney diseases, epilepsy, lupus, or rheumatoid arthritis.

The Legal Battle: Suing Pharmaceutical Companies and the State

The lawsuits initiated by X et al. targeted multiple defendants: the pharmaceutical companies that manufactured and sold chloroquine drugs, the medical institutions and physicians who prescribed them, and, crucially, the State of Japan (Y). The plaintiffs argued that the State, through the then Ministry of Health and Welfare, had failed in its regulatory duties concerning chloroquine. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court, settlements had been reached with the pharmaceutical companies and most medical institutions, leaving the State as the primary remaining defendant.

The core allegations against the State revolved around two main points:

- Illegality of Initial Approvals: That the Minister of Health and Welfare's initial manufacturing approvals for various chloroquine products were themselves illegal, given the emerging knowledge of risks.

- Failure to Exercise Regulatory Powers (Regulatory Inaction): That the Minister subsequently failed to take appropriate and timely regulatory measures—such as revoking or restricting the drug's approval for certain indications, mandating stronger warnings, or ordering its recall—despite accumulating evidence of the serious risk of chloroquine retinopathy.

This claim was brought under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Redress Act (国家賠償法 - Kokka Baishō Hō), which holds the State liable for damages caused by the intentional or negligent illegal acts of public officials in the exercise of public authority. The case proceeded under the former Pharmaceutical Affairs Act (薬事法 - Yakuji-hō), as the events predated later significant amendments to this law and the enactment of Japan's Product Liability Act.

A Timeline of Knowledge and State Actions:

- 1959 (International): The first significant international medical report (by Hobbs et al.) emerged, linking chloroquine to irreversible retinal damage.

- 1962 (Japan): The first case of chloroquine retinopathy was reported in Japanese medical literature. Over the next few years, more Japanese case reports and introductions of foreign literature on the subject appeared. These early reports generally warned of the risk of irreversible eye damage with long-term chloroquine use and emphasized the need for regular ophthalmological examinations, but they did not, at this early stage, entirely negate the drug's perceived overall utility for the conditions it was used to treat.

- 1960-1964 (Japan): During this period, the Minister of Health and Welfare granted manufacturing approvals for several chloroquine products (e.g., Kidora, CQC) for a range of indications, including kidney diseases, epilepsy, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis.

- 1967 (State Regulatory Action): Recognizing increasing concerns, the Minister designated chloroquine as a "powerful drug" and a "drug requiring physician's instruction" (要指示医薬品 - yōshiji iyakuhin), restricting its availability without a prescription.

- 1969 (State Regulatory Action): The Ministry of Health and Welfare, through its Pharmaceutical Affairs Bureau, issued a notice to prefectural governments. This notice instructed them to guide pharmaceutical manufacturers to strengthen the warnings in chloroquine package inserts. The revised warnings were to include information about the risk of retinal damage and other eye disorders with prolonged use, the necessity of adequate patient observation, and the need to discontinue the drug if abnormalities were detected. It also advised against prescribing chloroquine to patients with pre-existing retinal damage. These warnings were subsequently included in package inserts and published in medical journals.

- 1972 (State Regulatory Action): Following further reports of retinopathy cases collected through a new national side effect monitoring system (established in 1967 in the wake of the thalidomide tragedy), the Ministry consulted with an expert committee. This led to the formulation of specific "Guidelines for Vision Testing" to aid in the early detection of chloroquine retinopathy. The Ministry then directed pharmaceutical manufacturers to distribute 120,000 copies of a document titled "Notification Regarding Chloroquine-Containing Preparations," which included these testing guidelines, to relevant medical institutions. Manufacturers were also instructed to incorporate these guidelines into the package inserts for chloroquine products.

- 1976 (Official Re-evaluation by the Ministry): As part of a broader, ongoing re-evaluation of the efficacy and safety of all existing drugs (initiated in the early 1970s), the Ministry of Health and Welfare published its findings on chloroquine in July 1976. This re-evaluation concluded:

- Chloroquine was still considered effective and useful for malaria, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis.

- However, for kidney diseases (such as nephritis), while some efficacy was acknowledged, its benefits did not outweigh the risks of side effects, leading to a conclusion of lack of utility for these conditions.

- For epilepsy, there was insufficient evidence to confirm its efficacy.

The plaintiffs' exposure to chloroquine largely predated this critical 1976 re-evaluation. The lower courts had reached differing conclusions regarding the State's liability, with the Tokyo High Court ultimately denying it, leading to the plaintiffs' appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Framework for State Liability in Pharmaceutical Regulation

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of June 23, 1995, dismissed the plaintiffs' appeal, finding that the State was not liable under the State Redress Act. The Court's reasoning was based on a careful examination of the Minister of Health and Welfare's powers and duties under the then-existing Pharmaceutical Affairs Act and the standard for establishing "illegality" in regulatory inaction.

- The Minister's Regulatory Powers: The Court affirmed that the overarching purpose of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act was to ensure not only the quality but also the overall safety of pharmaceutical products, including safety from adverse side effects. Based on this purpose, the Court held that even under the former version of the Act (which lacked explicit provisions for revoking approvals of already marketed drugs found to be unsafe), the Minister of Health and Welfare possessed the authority to:

- Delete a drug from the official Japanese Pharmacopoeia or revoke its manufacturing approval if subsequent evidence revealed that its harmful side effects significantly outweighed its therapeutic efficacy, rendering it no longer useful as a medicine.

- Exercise various other statutory powers (e.g., designating drugs as "powerful" or "prescription-only," ordering reports from manufacturers, issuing emergency measures to prevent public health dangers) and utilize administrative guidance (指導勧告 - shidō kankoku) to direct pharmaceutical manufacturers to take necessary actions, such as strengthening warnings or restricting indications.

- The Standard for "Illegality" in Regulatory Non-Action: The Supreme Court established a high threshold for finding the State liable for failing to exercise these regulatory powers:

- The Minister's decision on whether, when, and how to exercise these powers involves a high degree of specialized professional and discretionary judgment. This judgment must be based on the medical and pharmaceutical knowledge and evidence available at the specific time the decision (or non-decision) is made.

- Consequently, the mere fact that harm occurs from a drug's side effects does not automatically mean that the Minister's prior failure to take (or to take stronger) regulatory action was "illegal" for the purposes of the State Redress Act.

- Regulatory inaction becomes "illegal" only if, judged against the medical and pharmaceutical knowledge available at that particular historical point, the non-exercise of regulatory power "deviates from the permissible limits of discretion and is found to be markedly lacking in rationality" (許容される限度を逸脱して著しく合理性を欠く - kyoyō sareru gendo o itsudatsu shite ichijirushiku gōrisei o kaku). This standard implies that liability would only attach if the Minister's failure to act was so unreasonable, given the information available at the time, that no reasonable regulator could have made such a choice.

Applying the Standard: Why the State Was Not Held Liable in the Chloroquine Case

The Supreme Court then applied this stringent standard to the specific facts surrounding chloroquine:

- Regarding the Initial Approvals (1960-1964): The Court found that the Minister's actions in approving chloroquine products during this period were not illegal.

- At that time, reports of chloroquine retinopathy were only beginning to emerge, both internationally and in Japan.

- The early literature, while warning of risks with long-term use, generally did not negate chloroquine's overall perceived utility for serious conditions like malaria, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis, for which it had international recognition and was listed in major pharmacopoeias.

- Its use for kidney disease and epilepsy also had some level of clinical support within Japan at that time, and was not yet definitively disproven.

- Given the limited number of reported retinopathy cases in Japan during this early period (a total of seven by 1965) and the prevailing medical and pharmaceutical understanding, the Court concluded that the Minister's assessment of chloroquine's utility as outweighing its then-known risks was not "markedly lacking in rationality."

- Regarding Subsequent Regulatory Actions (or Inactions) Prior to the 1976 Re-evaluation: The Court also found that the Minister's regulatory conduct in the period leading up to the 1976 re-evaluation did not meet the high threshold for "illegality."

- It acknowledged that the Ministry of Health and Welfare did take several regulatory steps as awareness of chloroquine retinopathy increased, including:

- Designating chloroquine as a "powerful drug" and a "drug requiring physician's instruction" in 1967.

- Directing manufacturers to strengthen warnings in package inserts in 1969.

- Issuing detailed guidelines for ophthalmological examinations for early detection in 1972 and requiring manufacturers to disseminate this information widely to medical professionals.

- The Court recognized that these measures were intended to prevent harm by ensuring that chloroquine was used under medical supervision and by alerting doctors and patients to the risks and the need for monitoring.

- While acknowledging that, in hindsight, particularly after the 1976 re-evaluation clearly negated chloroquine's utility for kidney disease and epilepsy, these earlier measures might appear insufficient in content or timing, the Supreme Court emphasized that their legality must be judged based on the scientific and medical knowledge available at the times those regulatory decisions were made (or not made).

- Crucially, the Court noted that throughout much of this period (before 1976), the prevailing view within the medical community, both in Japan and internationally, was that chloroquine remained a useful drug for several serious conditions, and its benefits were often considered to outweigh the risks of retinopathy, provided proper precautions were taken.

- Therefore, the Court concluded that the Minister's failure to take even more drastic actions (such as revoking approvals for certain indications, or mandating even stronger warnings than those implemented) before the comprehensive re-evaluation of 1976 did not constitute an exercise of discretion so flawed as to be "markedly lacking in rationality."

- It acknowledged that the Ministry of Health and Welfare did take several regulatory steps as awareness of chloroquine retinopathy increased, including:

The Primary Role of Manufacturers and Medical Professionals

While absolving the State of liability, the Supreme Court's judgment (and the lower court proceedings) implicitly underscored the primary responsibilities of pharmaceutical manufacturers and medical professionals in ensuring drug safety. Manufacturers have a duty to develop safe drugs, conduct thorough testing, monitor for side effects, and provide accurate and comprehensive warnings. Medical professionals have a duty to prescribe appropriately, inform patients of risks and benefits, and monitor for adverse reactions. The State's regulatory role, while crucial, is often one of oversight and setting standards, relying in part on the diligence of these other actors.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1995 decision in the Chloroquine Litigation established a very high threshold for holding the State of Japan liable for damages arising from the side effects of approved pharmaceutical drugs due to alleged regulatory inaction. Liability under the State Redress Act will only attach if the failure of the relevant minister (in this case, the Minister of Health and Welfare) to exercise regulatory powers is found to have been "markedly lacking in rationality" when assessed against the prevailing medical and pharmaceutical knowledge and standards at the time of the alleged inaction. This standard emphasizes the broad discretion afforded to regulatory authorities in making complex risk-benefit assessments for pharmaceuticals. The ruling highlighted that actions (or inactions) that may seem insufficient or erroneous in hindsight, with the benefit of later scientific understanding, will not necessarily be deemed illegal for the purposes of state compensation if they were within the bounds of rational discretion based on contemporaneous knowledge.